1. Overview

Queen Jinseong (진성여왕Jinseong yeowangKorean), personal name Kim Man (김만Gim ManKorean) or Kim Won (김원Gim WonKorean), was the 51st monarch of the Korean kingdom of Silla, reigning as its third and last queen from 887 to 897. Her ten-year rule marked a period of severe internal disarray, with widespread social unrest, economic collapse, and the effective fragmentation of the central government's authority, directly leading to the beginning of the Later Three Kingdoms period. While traditional historical accounts, such as the *Samguk Sagi*, often present a highly critical view of her reign, attributing the chaos to her alleged licentious conduct and political favoritism, contemporary records from figures like Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn offer a contrasting, more favorable assessment. This complex and controversial historical evaluation reflects the profound challenges Silla faced during her time on the throne.

2. Early Life and Accession

Queen Jinseong's ascension to the Silla throne followed a period of political instability and family succession issues, placing her in a unique position as a female monarch in a rapidly declining kingdom.

2.1. Birth and Family

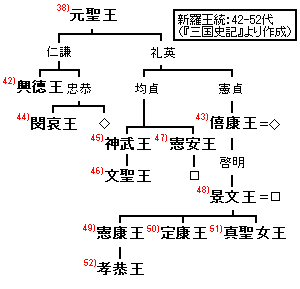

Jinseong was the only daughter of King Gyeongmun (reigned 861-875) and Queen Munui (문의왕후Munui wanghuKorean) of the Kim clan. Her exact birth year is unknown, but based on her mother's death in 870, she is believed to have been born between the mid-860s and 870. She was the younger sister of Heongang (reigned 875-886) and Jeonggang (reigned 886-887). Her paternal grandfather was Kim Kye-myŏng (김계명Gim Gye-myeongKorean), and her paternal grandmother was Madam Gwanghwa (광화부인Gwanghwa-buinKorean). Her maternal grandfather was King Heonan (헌안왕Heonan-wangKorean).

2.2. Accession to the Throne

Jinseong ascended to the throne in July 887, following the deaths of both of her older brothers, Heongang and Jeonggang, neither of whom left a male heir. King Jeonggang, suffering from illness and with no direct successor, appointed his younger sister Jinseong as his heir. He justified this controversial choice of a female monarch by citing the purportedly successful reigns of previous queens, Seondeok and Jindeok. Despite these historical precedents being invoked to legitimize her rule and inspire confidence, Queen Jinseong ultimately struggled to live up to the expectations set by her predecessors, as Silla was already in a state of severe decline.

3. Reign

Queen Jinseong's reign was characterized by an unprecedented level of internal turmoil, which saw the collapse of central authority and the emergence of independent regional powers, marking the beginning of the end for Silla.

3.1. Political and Social Disarray

During Jinseong's rule, public order collapsed, and the central government's control over the kingdom significantly weakened. The tax collection system failed, leading to a depleted national treasury, and the military conscription system became ineffective. This period was also marked by pervasive corruption within the court, where allegiances were based on personal gain rather than public service. Traditional historical accounts, such as the *Samguk Sagi*, specifically blame Jinseong's alleged licentious conduct, such as bringing attractive men into the palace for lewd acts and promoting them to important positions, as a primary cause for the deterioration of the state's discipline and governance. This led to widespread discontent among the populace, as evidenced by critical writings posted in public spaces. In 892, the queen also dissolved the Yeoseong Susagwan (여성수사관Yeoseong SusagwanKorean), a governmental institution that had been established for 160 years, because its members attempted to impeach her by finding fault with her actions, further highlighting the internal strife and the queen's autocratic responses to criticism.

3.1.1. Taxation Issues and Peasant Rebellions

The financial crisis under Queen Jinseong's reign became particularly severe, with the national treasury running empty due to royal extravagance and widespread corruption among court officials. In an attempt to address the dwindling finances, the government tried to tighten tax collection from local regions. However, this policy backfired because the taxes collected from the populace by local officials were often embezzled before reaching the central court. Consequently, peasants and the general populace were forced to pay taxes multiple times, leading to immense hardship and fueling widespread resentment.

This extreme burden on the people ignited numerous peasant uprisings and banditry throughout the kingdom. One notable rebellion was led by Wonjong and Aeno in Silla's southwestern regions in 889. These localized revolts, initially driven by poverty and unfair taxation, gradually transformed into organized anti-government groups. Additionally, Ajagae, the father of Gyeon Hwon, also led a local peasant uprising and established a base in Sangju. The queen's attempts to secure funding for the kingdom inadvertently strengthened these rebellious factions, further destabilizing her rule.

3.2. Rise of Local Warlords and the Later Three Kingdoms

The central government's loss of control over the provinces, combined with the ongoing peasant revolts, provided fertile ground for the emergence of powerful local warlords, known as *hojok* (호족hojokKorean). These *hojok* lacked strong loyalty to the central Silla court and gradually established themselves as de facto rulers of their respective territories.

Among the most prominent figures who took advantage of this domestic disarray were Gyeon Hwon and Gung Ye. Gyeon Hwon, a former Silla military officer, rebelled in the southwest, conquering regions that had previously been part of Baekje. In 892, he captured Wansanju (present-day Jeonju) and Mujinju (present-day Gwangju), gaining control over the former Baekje territories and securing the support of the local populace, who were hostile towards the Silla court. Gyeon Hwon subsequently established his own kingdom, Later Baekje, in 892. During this period, Gyeon Hwon also launched an attack on Daeyaseong (present-day Hapcheon), killing the defending general Kim Jeong-cheol, though he failed to capture the fortress.

Similarly, in the northwest, Yang Gil led a rebellion against Silla in Bukwon (present-day Wonju) in 891. A Silla royal family member who had become a monk, Gung Ye, initially joined Gyeon Hwon's forces in 891 but later left due to a lack of trust. Gung Ye then joined Yang Gil's rebel army in 892 and quickly rose through the ranks, eventually defeating Yang Gil and taking over leadership of the rebel forces. Gung Ye's forces conquered vast territories in the northwest, including Songak (present-day Kaesong), with the support of local leaders like Wang Ryung (왕륭Wang RyungKorean) and his son Wang Geon (왕건Wang GeonKorean), who would later found Goryeo. Wang Ryung and Wang Geon, local aristocrats in Songdo, quickly surrendered to Gung Ye's forces upon their arrival. By 895, Gung Ye had established his base in Myeongju (present-day Gangneung), effectively laying the groundwork for his own kingdom, which would become Later Goguryeo (or Taebong). These developments marked the effective beginning of the Later Three Kingdoms of Korea, signaling the irreversible decline of Unified Silla.

3.3. Efforts for State Reform

Recognizing the dire state of the kingdom, Queen Jinseong appointed the renowned Confucian scholar and government official Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn (최치원Choe ChiwonKorean) to the position of Achan (아찬AchanKorean, rank 6 of 17 official ranks) in 894. Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn, deeply concerned about the nation's decline, presented the queen with his "Ten Injunctions" (시무십조Simu SipjoKorean), a series of comprehensive reform proposals aimed at revitalizing the government and preventing Silla's collapse.

These proposals advocated for significant political reforms, including measures to improve governance, control corruption, and stabilize the economy. While Queen Jinseong initially appeared to accept his recommendations, establishing the Wonbongseong (원봉성WonbongseongKorean) in 895 to implement some changes, the entrenched corruption and resistance from powerful factions within the court ultimately led to the disregard of many of Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn's key suggestions. Ultimately, disappointed by the lack of meaningful reform and the court's inability to enact his vision, Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn, who had reportedly been reprimanded and demoted to a local official post in Daesan, eventually resigned from his official post at the age of 41 in 897, retreating to Mount Gaya to live in seclusion. His departure symbolized the central government's failure to effectively address the crisis, despite the efforts of capable individuals.

3.4. Controversies and Historiographical Issues

Queen Jinseong's reign is one of the most controversial in Silla history, largely due to the highly critical portrayal found in the *Samguk Sagi*, a primary historical text compiled in 1145 by Kim Bu-sik. This record frequently details her alleged licentious conduct, claiming she brought attractive young men into the palace for lewd acts and granted them important positions, leading to widespread political corruption and the erosion of governmental authority. It also alleges an affair with her paternal uncle and high commander (Gakgan) Kim Wi-hong (김위홍Kim Wi-hongKorean), whom she allegedly married in 880 according to some genealogical records of the Gyeongju Kim clan, and had three sons with, Kim Yang-jeong, Kim Jun, and Kim Cheo-hoe. Upon Kim Wi-hong's death, she bestowed upon him the posthumous title of Hyeseongdaewang (혜성대왕HyeseongdaewangKorean).

The *Samguk Sagi* and *Samguk Yusa* (another historical record) further describe her as indulging in excessive spending, leaving the national treasury empty, and being unable to curb the power of corrupt officials like her wet nurse Buho-buin (부호부인Buho-buinKorean) and her consort Kim Wi-hong. These records suggest that her personal conduct directly led to the downfall of the kingdom, including the proliferation of banditry and peasant uprisings.

However, it is crucial to consider the potential biases of these historical texts. The *Samguk Sagi* was written from a strong Confucian perspective, which generally held a negative view of female rule and often attributed national decline to the moral failings of monarchs, especially women. This critical stance is comparable to how Chinese Empress Wu Zetian was often portrayed in Confucian histories.

In stark contrast, the contemporary records of Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn, a prominent scholar and official during Jinseong's reign, present a more favorable image of the queen. In his "Table of Acknowledging the Succession" (사사위표Sasa-wipyoKorean), Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn describes Jinseong as a monarch with "no greed," a "kind heart," and a "strong will." He states that she had many illnesses, preferred tranquility, spoke only when necessary, and was firm in her convictions. Other writings by Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn, such as the Stele Inscription for National Preceptor Nanghye at Seongjusa Temple in Boryeong, also portray her as a benevolent ruler. This discrepancy highlights the complexity of assessing her reign, suggesting that the kingdom's decline was likely due to deep-seated systemic issues rather than solely the queen's personal conduct, though her leadership undoubtedly contributed to the challenges faced by Silla. Furthermore, Silla's diminished international standing during her reign was underscored by diplomatic incidents, such as the 895 dispute in Tang Dynasty China, where envoys from Balhae reportedly referred to themselves as "Malgal" (말갈MalgalKorean) or "small tributary of Silla," while implicitly or explicitly acknowledging Silla as a superior state, reflecting a shift in regional power dynamics.

4. Later Years and Demise

The final period of Queen Jinseong's reign was marked by her recognition of the kingdom's irreversible decline and her subsequent decision to abdicate.

4.1. Appointment of Crown Prince and Abdication

As the political and social chaos escalated, Queen Jinseong, suffering from illness, decided to abdicate the throne. In 895, she appointed Kim Yo (김요Kim YoKorean), the illegitimate son of her older brother King Heongang, as Crown Prince. This choice solidified the succession plans for the crumbling kingdom. She officially abdicated on July 4, 897 (the first day of the sixth lunar month).

4.2. Death and Burial

Queen Jinseong died shortly after her abdication, on December 31, 897 (the fourth day of the twelfth lunar month). She was buried to the north of Sajasa Temple (사자사SajasaKorean) in Gyeongju, specifically in the north palace of Gyeongju, the capital of Silla. Her death marked the end of her tumultuous ten-year reign, which is widely seen as the final phase of Unified Silla before its eventual collapse into the Later Three Kingdoms.

5. Legacy and Assessment

Queen Jinseong's legacy remains a subject of historical debate, caught between traditional criticisms and more nuanced contemporary accounts.

5.1. Cultural Contributions

Despite the political and social turmoil of her reign, Queen Jinseong is noted for one significant cultural undertaking: she commissioned the compilation of the *Samdaemok* (삼대목SamdaemokKorean). This work, ordered in 888 and overseen by Kim Wi-hong and the Buddhist monk Dae Gu Hwasang, was a collection of *hyangga*, Silla's traditional folk songs. Although the *Samdaemok* is no longer extant, its creation represents a valuable effort to preserve Silla's unique poetic and musical heritage.

5.2. Historical Evaluation

The historical evaluation of Queen Jinseong's reign is highly controversial and often contradictory. Traditional Korean historical texts, particularly the *Samguk Sagi* and *Samguk Yusa*, present a overwhelmingly negative portrayal. They accuse her of incompetence, excessive indulgence, and moral corruption, directly linking her alleged licentious behavior and favoritism towards attractive men to the collapse of state authority, widespread rebellions, and the overall decline of Silla. These accounts suggest that her personal failings were a primary cause of the kingdom's misfortunes.

However, a contrasting perspective emerges from the writings of her contemporary, Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn. His documents describe her as a kind-hearted monarch, devoid of greed, and willing to accept reform proposals, despite her recurring illnesses. This disparity in historical records highlights the importance of considering the context and potential biases of their authors. Confucian scholars, who compiled the *Samguk Sagi*, generally held a negative view of female rulers, often attributing societal problems to their supposed moral deficiencies.

In modern historical analysis, there is a tendency to view Silla's decline during Jinseong's reign as the culmination of deep-seated systemic issues that had been festering for decades, rather than solely the result of her individual character. The weakening of central authority, the rise of powerful local warlords, and the breakdown of the tax system were long-term trends exacerbated by a succession of weak kings before her. While Jinseong's leadership likely contributed to the chaotic situation, it is acknowledged that she inherited a kingdom already on the brink. Her reign, therefore, serves as a critical turning point that formally ushered in the Later Three Kingdoms period.

6. Family

Queen Jinseong's family lineage is as follows:

| Relation | Name (Birth-Death) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Father | King Gyeongmun (841-875, reigned 861-875) | |

| Paternal Grandfather | Kim Kye-myŏng | |

| Paternal Grandmother | Madam Gwanghwa | |

| Mother | Queen Munui of the Kim clan | |

| Maternal Grandfather | King Heonan | |

| Siblings | Older brother: King Heongang (reigned 875-886) | |

| Older brother: King Jeonggang (reigned 886-887) | ||

| Consort | Kim Wi-hong (김위홍Kim Wi-hongKorean, 845-888), also known as King Hyeseong (혜성왕HyeseongwangKorean) | Of the Gyeongju Kim clan; her paternal uncle, being the second son of Kim Kye-myŏng and Lady Gwanghwa. |

| Issue (with Kim Wi-hong) | Son: Kim Yang-jeong (김양정Kim Yang-jeongKorean, born 882) | |

| Son: Kim Jun (김준Kim JunKorean, born 883) | ||

| Son: Kim Cheo-hoe (김처회Kim Cheo-hoeKorean, born 885) |

7. In Popular Culture

Queen Jinseong has been depicted in various modern popular culture works, often with interpretations that reflect the historical controversies surrounding her character and reign.

- In television, she was portrayed by Noh Hyun Hee in the 2000-2002 KBS1 TV series Taejo Wang Geon, which dramatizes the rise of Wang Geon and the Later Three Kingdoms period.

- In film, she has appeared in several productions:

- In the 1964 film Jinseong Yeowang, she was played by Do Geum-bong.

- In the 1969 film The Legend of the Evil Lake, she was portrayed by Kim Hye-jeong.

- She was again depicted by Kim Hye-ri in the 2003 remake of The Legend of the Evil Lake.