1. Life

Jan Swammerdam's life was marked by an early interest in natural history, rigorous medical training, persistent scientific inquiry despite financial and personal challenges, and a late-life spiritual reevaluation that influenced his scientific output.

1.1. Early life and education

Jan Swammerdam was baptized on February 15, 1637, in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam. His father, Jan Jacobsz Swammerdam (d. 1678), was an apothecary and an enthusiastic amateur collector of minerals, coins, fossils, and insects from around the world, cultivating an early interest in natural curiosities in his son. His mother, Baartje Jans (d. 1660), passed away when he was 24. The family lived across from the Montelbaanstoren, near the harbor, which housed the headquarters and warehouses of the Dutch West India Company, where his uncle worked. As a youngster, Swammerdam often assisted his father in managing his extensive cabinet of curiosities.

Despite his father's desire for him to pursue theology, Swammerdam began studying medicine in 1661 at the University of Leiden. There, he received instruction from prominent figures such as Johannes van Horne and Franciscus Sylvius. His fellow students included several individuals who would become notable in their own right, such as Frederik Ruysch, Reinier de Graaf, Ole Borch, Theodor Kerckring, Steven Blankaart, Burchard de Volder, Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, and Niels Stensen. During his medical studies, Swammerdam also began to assemble his own collection of insects.

In 1663, Swammerdam traveled to France to further his education, possibly accompanied by Stensen. He spent a year studying at the Protestant University of Saumur under the guidance of Tanaquil Faber. Subsequently, he moved to Paris to study at the scientific academy organized by Melchisédech Thévenot, visiting places like Issy and Saumur. He returned to the Dutch Republic in 1665 and joined a group of physicians engaged in performing dissections and publishing their findings. Between 1666 and 1667, Swammerdam concluded his medical studies at the University of Leiden, earning his medical doctorate in 1667 under van Horne. His dissertation focused on the mechanism of respiration, published under the title De respiratione usuque pulmonum.

1.2. Early career and financial struggles

After qualifying as a doctor, Jan Swammerdam chose to dedicate himself primarily to the study of insects, a decision that led to conflict with his father, who desired him to establish a medical practice and earn a living. Despite the pressure, Swammerdam persevered in his research. His father eventually withdrew all financial support following the publication of Swammerdam's Historia insectorum generalis in late 1669.

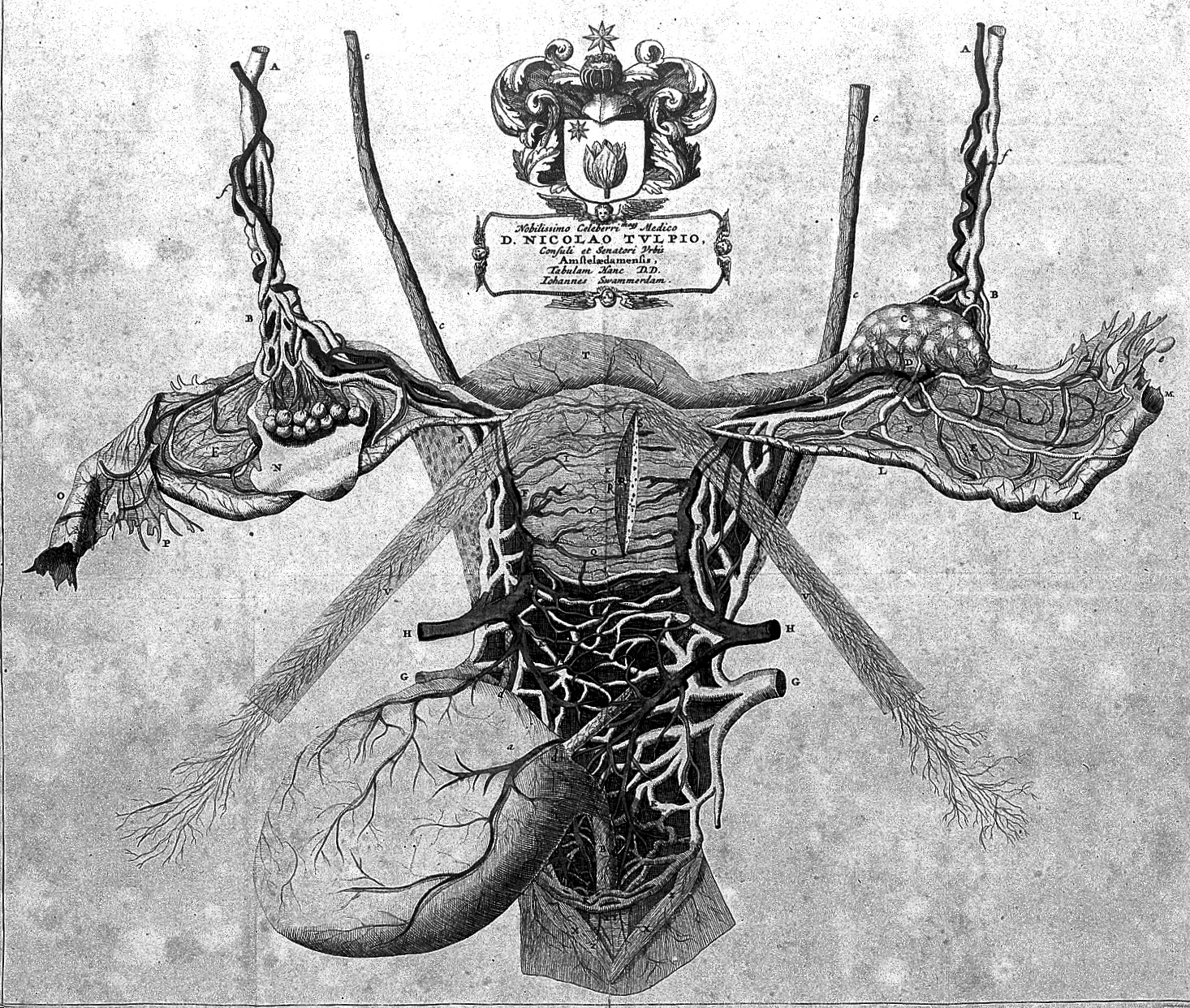

To finance his ongoing scientific work, Swammerdam was compelled to practice medicine sporadically. He obtained permission in Amsterdam to perform dissections on the bodies of patients who died in hospitals. During this period, he also collaborated with Johannes van Horne on research into the anatomy of the uterus, which was published in 1672 under the title Miraculum naturae sive uteri muliebris fabrica. Swammerdam later accused his contemporary, Reinier de Graaf, of unfairly claiming credit for discoveries he and Van Horne had made regarding the importance of the ovary and its eggs. Swammerdam corresponded with Matthew Slade and Paolo Boccone and received visits from prominent figures like Willem Piso, Nicolaas Tulp, and Nicolaas Witsen.

1.3. Spiritual crisis and later life

In the mid-1670s, Jan Swammerdam experienced a profound spiritual crisis. Having initially viewed his scientific investigations as a form of homage to the Creator, he began to fear that his intense focus on curiosities might amount to idolatry. In 1673, he briefly came under the influence of the Flemish mystic Antoinette Bourignon, who performed mystical healing in hospitals. This period led to a temporary interruption of his scientific work.

His 1675 treatise on the mayfly, titled Ephemeri vita, reflected this shift, incorporating devout poetry and documenting his religious experiences. Swammerdam found solace within Bourignon's sect in Nordstrand, Germany. During this time, he traveled to Copenhagen to visit the mother of Niels Stensen, who had been his fellow student. He also famously declined an offer from Cosimo III de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to purchase his insect collection for 12.00 K NLG and continue his studies in Florence.

However, Swammerdam's religious crisis only briefly halted his scientific pursuits. By early 1676, he was back in Amsterdam and resumed his work, as indicated by a letter to Henry Oldenburg stating, "I was never at any time busier than in these days, and the chief of all architects has blessed my endeavors." He continued to work on what would become his magnum opus until his premature death at the age of 43 in 1680. It is believed that he died of malaria and also suffered from a nervous breakdown in his later years. He was buried in the Walloon church in Amsterdam, where some of his siblings and his father were also interred.

2. Major Scientific Contributions

Jan Swammerdam's scientific endeavors spanned a wide range of biological fields, characterized by his pioneering use of microscopy and his meticulous, experimental approach.

2.1. Microscopy and anatomical techniques

Swammerdam was a pioneer in the use of the microscope for anatomical dissections. He developed and employed innovative techniques that allowed for unprecedented detail in his observations. Among his most notable advancements was the invention of the **wax injection technique**, which involved injecting wax into blood vessels to make them more visible and easier to study during dissection. This method, along with his meticulous preparation of hollow human organs, became widely adopted in anatomical studies for centuries. He often used a single-lens microscope made by Johannes Hudde, which, despite its simplicity, allowed him to achieve remarkable clarity and precision in his observations.

2.2. Research on insects

Swammerdam's primary field of study was entomology, the study of insects. He rigorously challenged the prevailing Aristotelian notions of his time, which often regarded insects as imperfect animals lacking internal anatomy and considered them less important than fish or other animals. He particularly opposed the concepts of spontaneous generation and metamorphosis. He opposed the idea of spontaneous generation, which suggested that some creatures, especially insects, could arise spontaneously from non-living matter, arguing that such a belief implied that parts of the universe were excluded from God's will. Swammerdam contended that all creation was uniform and stable, constantly manifesting God's design. Influenced by René Descartes's natural philosophy, which held that nature was orderly and governed by fixed laws, Swammerdam sought to explain natural phenomena rationally.

He asserted that the generation of all creatures, including insects, adhered to the same universal laws. He maintained that all insects originated from eggs, and their limbs developed and grew slowly, refuting the idea of a sudden, drastic change or the notion that different life stages represented distinct individuals. This perspective eliminated the perceived distinction between insects and so-called 'higher animals', asserting that all life followed a continuous developmental process. Swammerdam vehemently opposed "vulgar errors" and criticized the symbolic interpretation of insects, viewing it as incompatible with the omnipotent power of God, whom he saw as the ultimate architect of creation.

2.2.1. Historia Insectorum Generalis

In late 1669, Swammerdam published his significant work Historia insectorum generalis ofte Algemeene verhandeling van de bloedeloose dierkens (The General History of Insects, or General Treatise on little Bloodless Animals). This treatise summarized his extensive studies of insects collected in France and around Amsterdam. In it, he systematically countered the prevailing Aristotelian notion that insects were imperfect animals lacking internal anatomy. He also directly challenged the then-common Christian idea that insects originated from spontaneous generation and that their life cycle involved a true metamorphosis, meaning a sudden transformation from one type of animal into another. Instead, Swammerdam provided detailed evidence that insects undergo a gradual development from an egg, with their forms evolving rather than undergoing an abrupt, fundamental change.

2.2.2. Research on bees

Swammerdam devoted five intense years to beekeeping and meticulous observation of bee colonies. Before his work, it had been asserted since ancient times that the "king bee" ruled the hive, although Luis Mendez de Torres (1586) had identified the ruler as female, while Charles Butler (1609) correctly identified drones as male. Swammerdam made a revolutionary discovery regarding the reproductive organs of bees, particularly confirming that the traditional "king bee" was, in fact, a queen bee. He substantiated this by finding eggs inside the creature, though he did not publish this specific finding immediately. Building on this, he provided conclusive evidence that the queen bee is the **sole mother of the colony**, a revelation that revolutionized the understanding of bee social structures. He also identified drones as masculine and lacking stingers. While he described worker bees as "natural eunuchs" due to his inability to detect ovaries in them, he correctly noted their closer affinity to the female nature.

His detailed drawing of the queen bee's reproductive organs, observed through the microscope, was a critical piece of evidence. Although it was only published posthumously in 1737 within Bybel der natuureDutch, details of his bee research had already been disseminated through his correspondence. Similarly, his accurate drawing of the honeycomb geometry, also included in Bybel der natuureDutch, had already been referenced by other scientists, such as Giacomo Filippo Maraldi in his 1712 book, due to Swammerdam's earlier sharing of his findings through correspondence. Notably, Nicolas Malebranche referenced Swammerdam's bee research as early as 1688, indicating the early dissemination and impact of his discoveries.

2.3. Research on muscle contraction

Swammerdam made significant contributions to physiology through his research on muscle contraction, notably playing a key role in refuting the prevalent "balloonist theory." This theory, supported by figures like the ancient Greek physician Galen and later elaborated by René Descartes, proposed that nerves were hollow tubes through which "animal spirits"-analogous to fluids or gases-flowed from the brain into muscles. According to this hypothesis, muscles would visibly enlarge when they contracted, due to the influx of these spirits.

To test this, Swammerdam designed a clever experiment using a severed frog thigh muscle. He placed the muscle in an airtight glass syringe with a small amount of water at the tip, allowing him to observe any change in the water level. When he stimulated the nerve to cause the muscle to contract, he observed that the water level did not rise; instead, it slightly lowered. This demonstrated conclusively that no air or fluid was flowing into the muscle during contraction, thereby debunking the balloonist theory. Swammerdam's findings had profound implications for neuroscience, suggesting that muscle movement was not due to an influx of spirits but rather to a direct response to nerve stimulation, laying the groundwork for the modern understanding of behavioral neuroscience based on stimuli. Swammerdam's research on muscles concluded after Nicolas Steno had published the second edition of his work, Elements of Myology, in 1669, which is referenced in Bybel der natuureDutch.

Swammerdam's research on muscle contraction was referenced by Steno before its formal publication in Bybel der natuureDutch. Steno, who had visited Swammerdam in Amsterdam, even hinted that Swammerdam's findings in this area contributed to his spiritual crisis. In a 1675 letter to Marcello Malpighi, Steno mentioned that Swammerdam had destroyed a treatise on the subject, preserving only the figures, and was "seeking God, but not yet in the Church of God."

2.4. Other anatomical and physiological discoveries

Beyond his primary focus on insects, Jan Swammerdam made several other important anatomical and physiological discoveries. In 1658, he was the first to observe and accurately describe red blood cells, a fundamental contribution to hematology. He also identified the valves in lymph vessels, sometimes referred to as "Swammerdam valves," which are crucial for the one-way flow of lymph.

In 1665, using his simple microscope, Swammerdam was among the first to observe the process of cell division in the eggs of frogs. He also conducted detailed anatomical studies of the female uterus in collaboration with Johannes van Horne, publishing their findings in Miraculum naturae sive uteri muliebris fabrica in 1672. Furthermore, Swammerdam made a significant observation by discovering the nascent limbs and wings of a butterfly inside a caterpillar, which are now known as imaginal discs. He demonstrated this revolutionary finding to Cosimo III de' Medici, underscoring his remarkable ability to uncover hidden biological structures through meticulous microscopic dissection.

3. Major Works

Jan Swammerdam's contributions to science are primarily documented in his two major published works, one of which was published during his lifetime and the other posthumously.

3.1. Bybel der natuure

Swammerdam's magnum opus, Bybel der natuureDutch (or Biblia naturae in Latin, meaning "The Bible of Nature"), was his main scientific work. Although he worked on it until his premature death in 1680, it remained unpublished during his lifetime. The complete work was eventually compiled and published posthumously in 1737 by Herman Boerhaave, a renowned professor at Leiden University.

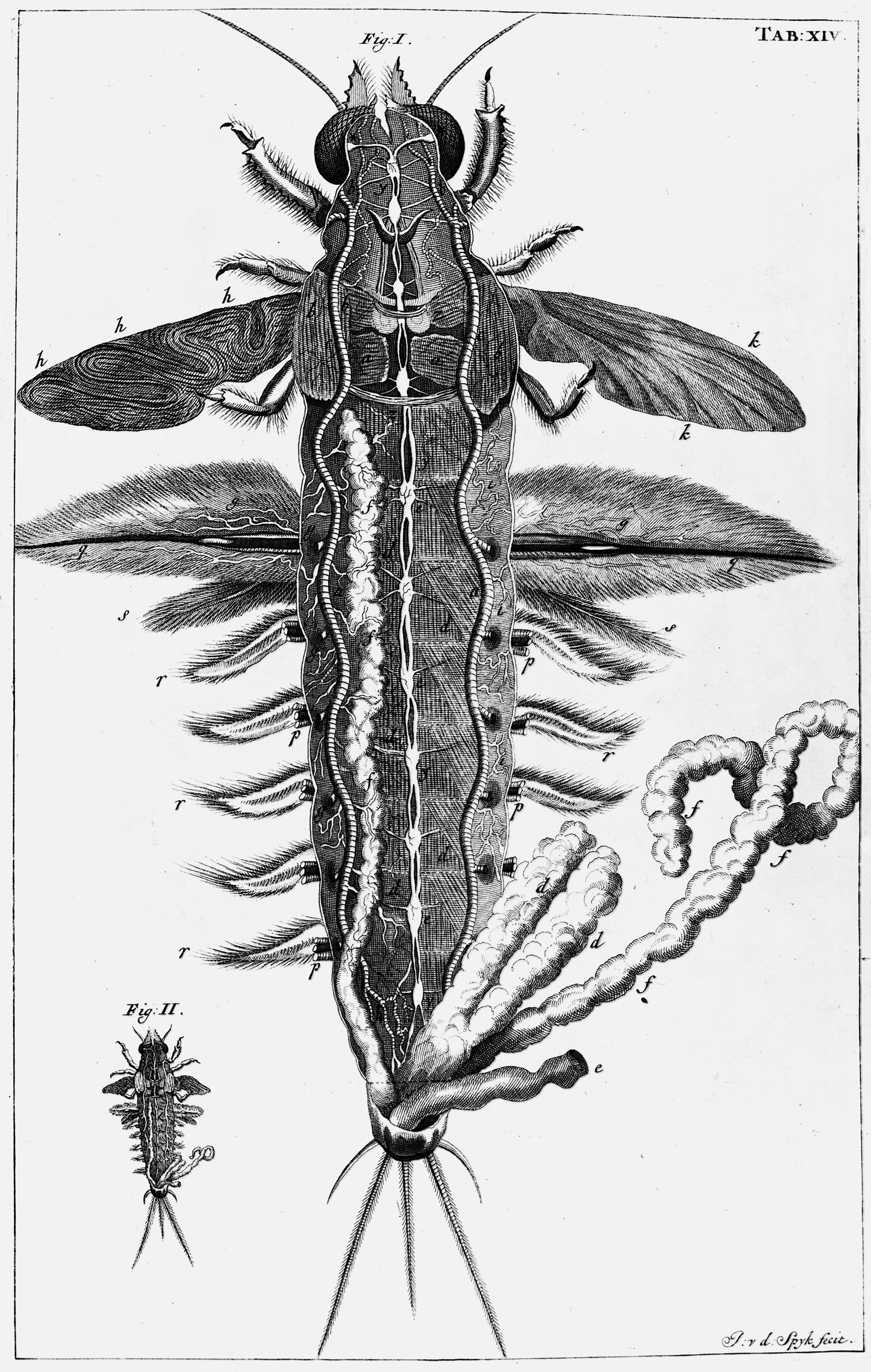

Driven by his conviction that all insects were worthy of study, Swammerdam compiled an epic treatise detailing the anatomy and life cycles of numerous insects using his microscope and dissection skills. The content included extremely detailed dissections of various insects such as silkworms, mayflies, ants, stag beetles, cheese mites, and bees. His scientific observations in Bybel der natuureDutch were deeply intertwined with his religious beliefs, reflecting his conviction in God as the almighty creator. A famous passage from the work exemplifies this, where Swammerdam praises the louse: "Herewith I offer you the Omnipotent Finger of God in the anatomy of a louse: wherein you will find miracle heaped on miracle and see the wisdom of God clearly manifested in a minute point." The work also included his groundbreaking visual proofs and detailed drawings, such as those of the queen bee's reproductive organs. An English translation of his entomological works, titled The Book of Nature; or, the History of Insects, was later published by Thomas Floyd in 1758.

4. Legacy and Evaluation

Jan Swammerdam's legacy is defined by his profound impact on scientific methodology, his pioneering biological discoveries, and his role in shaping natural philosophy.

4.1. Impact on science

Swammerdam's most enduring legacy lies in his innovative research methodologies. He is remembered as much for his meticulous techniques and skill with microscopes as for his specific discoveries. He developed novel methods for examining, preserving, and dissecting specimens, including the pioneering wax injection technique for visualizing blood vessels and a unique approach for preparing hollow human organs, which became standard practice in anatomy for centuries. His work influenced prominent contemporaries such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Nicolas Malebranche, who utilized his microscopic research to support their own natural and moral philosophies. Swammerdam is also credited with foreshadowing the natural theology of the 18th century, a movement that sought to find evidence of God's grand design in the intricate mechanics of the Solar System, the seasons, snowflakes, and the human anatomy. His Historia insectorum generalis was widely acclaimed and quickly translated into French (1682) and Latin (1685) after his death. John Ray, a celebrated English naturalist, lauded Swammerdam's methods as "the best of all" in his 1705 Historia insectorum.

4.2. Historical significance and reception

Jan Swammerdam holds a significant position in the history of science as one of the most meticulous and innovative early microscopists. His insistence on direct observation and experimental verification, coupled with his exceptional skill in microscopic dissection, set a new standard for biological research. His extensive collection, amassed with his father, consisted of 6,000 objects housed in 27 drawer cabinets, reflecting the breadth of his curiosity.

Despite his immense contributions, a notable detail in his historical reception is the absence of any confirmed authentic portrait of Jan Swammerdam. The images commonly associated with him are often derived from other works, like Rembrandt's painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, where the depicted figure is actually Hartman Hartmanzoon (1591-1659), a leading Amsterdam physician. This lack of an authentic visual record contrasts with the profound and lasting impact of his scientific work, which continues to be recognized for its rigor and insight.