1. Overview

James Mill (born James Milne; Jeamis MilleJames MillScots; 1773-1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher who became a prominent figure in the British intellectual and political landscape during the early 19th century. Initially educated for a career in the Church of Scotland, he moved to London and became a key proponent of utilitarianism, extensively collaborating with Jeremy Bentham. Mill made significant contributions to classical economics, psychology, and historical writing, most notably with his multi-volume work, The History of British India. As an influential member of the Philosophical Radicals, he championed social and political reforms, advocating for a broader franchise and improved governance. However, his work, particularly his writings on India, has been subject to considerable criticism for its perceived Eurocentric biases, reliance on secondary sources, and justification of British imperialism through the portrayal of Indian society as inherently "barbaric" or "inferior". He is also widely known as the father of the renowned philosopher John Stuart Mill.

2. Early Life and Education

James Mill was born on April 6, 1773, as James Milne, in Northwater Bridge, located in the parish of Logie Pert, Angus, Scotland. His father, also named James Milne, was a shoemaker and a small farmer. His mother, Isabel Fenton, came from a family that had faced hardships due to their connections with the Jacobite risings. Driven by a strong desire for her son to receive an excellent education, she ensured he attended the parish school and then the Montrose Academy, where he studied until the relatively late age of seventeen and a half. Mill subsequently enrolled at the University of Edinburgh, distinguishing himself as a proficient Greek scholar and completing his education in theology.

3. Religious and Moral Philosophy

Though raised in the tenets of Scotch Presbyterianism, James Mill's personal studies and reflections led him to reject not only the belief in Revelation but also the foundations of what is commonly referred to as Natural religion. He became critical of the prevailing Christian practices of his time, particularly the use of concepts like the afterlife and hell to regulate worldly life, viewing them with disdain. Mill eventually adopted a stance akin to that of Lucretius, opposing all religions as moral evils. He contended that the origins of humanity, much like the origins of God, were unknowable.

Mill's moral ideal was profoundly influenced by Socrates, a conviction he diligently instilled in his son, John Stuart Mill. His outlook on life incorporated elements of Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Cynicism. He established a criterion for good and evil based on whether an action was practical, producing pleasure or pain. However, in his later years, he came to believe that most pleasures were not worth the price that had to be paid for them. Consequently, he emphasized "temperance" as the highest virtue, advocating for it to be at the core of education. Mill also observed that the contemporary emphasis on "emotion" was a lamentable habit compared to ancient times, viewing it as an impediment to righteous conduct. He asserted that the goodness or badness (utility) of an action should be judged based on the action itself, rather than the actor's motives.

4. Relationship with Jeremy Bentham

In 1808, James Mill formed a close acquaintance with Jeremy Bentham, who was twenty-five years his senior. This relationship quickly evolved into a profound intellectual partnership, with Bentham becoming Mill's principal companion and ally for many years. Mill wholeheartedly adopted Bentham's principles of utilitarianism and dedicated his efforts to promoting and disseminating these ideas globally. Bentham provided significant financial and intellectual support, which enabled Mill to secure an economic and social foothold in England. Their collaboration was instrumental in the development and popularization of utilitarian thought, making Mill a central figure in the movement.

5. Career and Public Service

James Mill's career spanned various fields, from an early ministerial role to a significant position within the British colonial administration, alongside his prolific intellectual endeavors.

5.1. East India Company Career

After a brief and unsuccessful period as an ordained minister of the Church of Scotland, where his sermons were reportedly difficult for his congregation to understand, Mill moved to London in 1802 to pursue a literary career. In 1819, following the publication of his monumental work, The History of British India, he secured an influential position within the East India Company, specifically in the department of the Examiner of Indian Correspondence. His expertise and dedication led to his gradual rise through the ranks. By 1830, he was appointed head of the office, initially earning an annual salary of 1.90 K GBP, which increased to 2.00 K GBP by 1836. In this capacity, he became the official spokesperson for the Company's Court of Directors, particularly during the controversy surrounding the renewal of its charter from 1831 to 1833.

5.2. Influence on British Politics

Mill played a pivotal role in British politics, emerging as a dominant figure in the establishment of "philosophic radicalism". This group, which aimed for fundamental social reform based on Benthamite principles, saw Mill as a practical leader, effectively guiding the younger generation of activists. His writings on government and his considerable personal influence among Liberal politicians of his era significantly shifted political discourse. He moved the focus from French Revolution-era theories of natural rights and absolute equality towards advocating for governmental safeguards through a broad extension of the franchise. This framework became central to the fight for and eventual success of the Reform Bill.

6. Major Works and Intellectual Contributions

James Mill's intellectual output was diverse and impactful, spanning history, economics, and psychology, establishing him as a polymath of his time.

6.1. The History of British India

The History of British India, published in three volumes in 1818, is James Mill's most renowned and controversial work. This lengthy undertaking, which occupied him for twelve years (far longer than his initial expectation of three or four), detailed England's, and later the United Kingdom, acquisition of the Indian Empire. The book gained immediate and lasting success, significantly influencing the entire system of governance in British India. Mill's approach was largely theoretical rather than empirical, as he never visited India himself, relying solely on documentary material and archival records for his compilation. He was the first historian to propose a three-part classification of Indian history into Hindu, Muslim, and British periods, a classification that proved to be highly influential in subsequent Indian historical studies.

Mill portrayed Indian society as morally degraded and asserted that Hindus had never achieved "a high state of civilisation". He characterized Indians as barbaric and incapable of self-government, describing them as possessing a "general disposition to deceit and perfidy." He also argued that the "same insincerity, mendacity, and perfidy; the same indifference to the feelings of others; the same prostitution and venality" were conspicuous characteristics of both Hindus and Muslims. Mill viewed Hindus as often "penurious and ascetic," similar to "eunuchs" in their slave-like qualities. He extended these criticisms to the Chinese, stating both groups were "dissembling, treacherous, mendacious, to an excess which surpasses even the usual measure of uncultivated society," given to "excessive exaggeration with regard to everything relating to themselves," "cowardly and unfeeling," and "disgustingly unclean in their persons and houses." This work became a foundational text for British colonial administrators, often referred to as their "bible."

6.2. Elements of Political Economy

Mill's significant work on economics, Elements of Political Economy, was published in 1821, with a third revised edition appearing in 1825. This work built upon the economic views of his close friend, David Ricardo, and by the early 20th century, was considered primarily of historical interest as a summary of economic theories that had largely been discarded. Among its more important theses, Mill argued:

- That the primary challenge for practical reformers was to limit population growth, under the assumption that capital does not naturally increase at the same rate as population.

- That the value of a commodity depends entirely on the quantity of labor invested in its production.

- That what is now known as the "unearned increment" of land (the increase in value of land due to external factors rather than owner's effort) is an appropriate target for taxation.

6.3. Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind

In 1829, James Mill published Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind, a work that secured his position in the history of psychology and ethics. While not considered his primary work by many contemporary thinkers, it became a crucial text for the development of psychology, especially the school of associationism. Mill approached the problems of the mind similarly to the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers like Thomas Reid, Dugald Stewart, and Thomas Brown, but he introduced novel ideas, partly influenced by David Hartley and significantly by his own independent thought.

Mill extended the principle of association to analyze complex emotional states such as affections, aesthetic emotions, and moral sentiments, attempting to reduce them to pleasurable and painful sensations. The key strength of the Analysis lies in its persistent pursuit of precise definitions for terms and clear statements of doctrines. His views, as laid out in the book, are fundamentally similar to John Locke's concept of idea. Mill posited that sensory perception results from the direct contact of human sensory organs with external stimuli, while an "idea" is a mental copy of that perception that emerges in memory. He believed it was difficult to separate perception from ideas, as perception gives rise to ideas, and ideas cannot exist without prior sensory experience. Mill further argued that ideas can be linked to one another through a mechanism he called "association," which, according to him, operates under a single law: the law of contiguity.

He formulated three criteria for determining the strength of an association:

- Constancy: A strong association is permanent, meaning it is always present whenever recalled. Less permanent associations are weaker and tend to fade over time.

- Certainty: An association is strong if the individual making the association is genuinely convinced of its correctness.

- Facility: An association is strong if the surrounding environment provides sufficient means or facilities that simplify its formation, eliminating the need for intense thought or imagination to create the association.

Mill's work had a considerable impact on later empirical psychologists, including Franz Brentano.

6.4. Other Writings

Beyond his major works, James Mill contributed numerous essays and articles to various periodicals, reflecting his wide-ranging intellectual interests and his commitment to social reform. He wrote extensively for publications like the Literary Journal, St James's Chronicle, Edinburgh Review, Anti-Jacobin Review, British Review, The Eclectic Review, Annual Review, Philanthropist, and The Westminster Review.

Notable among his other writings are:

- An Essay on the Impolicy of a Bounty on the Exportation of Grain (1804), arguing against tariffs on grain exports.

- Commerce Defended (1808).

- Articles for the Encyclopædia Britannica (fifth edition supplement) in 1814, including significant expositions on "Jurisprudence," "Prisons," "Government," and "Law of Nations," which offered insights into utilitarianism.

- Essays on Government, Jurisprudence, Liberty of the Press, Education, and Prisons and Prison Discipline (1823), collecting several of his influential articles.

- Essay on the Ballot and Fragment on Mackintosh (1830), where the latter critically examined James Mackintosh's Dissertation on the Progress of Ethical Philosophy (1830) from a utilitarian perspective.

- "The Church and its Reform" (1834), an article for the London Review that was highly skeptical of the ecclesiastical establishment.

- "Whether Political Economy is Useful" (1836).

- The Principles of Toleration (1837), published posthumously.

Mill's contributions to the Philanthropist (1811) were particularly extensive, focusing on topics like education, freedom of the press, and prison discipline (including expounding Bentham's Panopticon). He also launched powerful criticisms against the Church during the Bell and Lancaster controversy and participated in discussions that led to the founding of the University of London in 1825.

7. Views on India and Imperialism

James Mill's perspectives on India and his justification of British imperialism are a significant aspect of his legacy, often drawing substantial criticism. Despite never having visited the Indian subcontinent, and lacking knowledge of Indian languages like Hindi, Mill extensively wrote The History of British India based solely on English-language documents and archival records. This methodology has been a focal point of critique, as it allowed him to present a highly generalized and often prejudiced view of Indian society.

Mill justified British rule over India on utilitarian grounds, viewing it as part of a "civilising mission" for Britain to impose its governance on what he considered a morally degraded society. He argued that Indians, and other Asian peoples like the Chinese, Persians, Arabs, Japanese, Cochinchinese, Siamese, Burmese, Malays, and Tibetans, possessed "lower civilizations" and were inherently "inferior nations." He famously claimed that "under the glosing exterior of the Hindu, lies a general disposition to deceit and perfidy," and that Indians were "incapable of self-government." He further asserted that "the Hindoo like the eunuch, excels in the qualities of a slave."

His work propagated the idea that British intervention was necessary to "improve" Indian society, a view that resonated with colonial administrators who used his History as a guide. This portrayal of Indian culture and people, based on secondary sources and preconceived notions, is widely seen as a quintessential example of Western-centric imperialist theory.

8. Personal Life

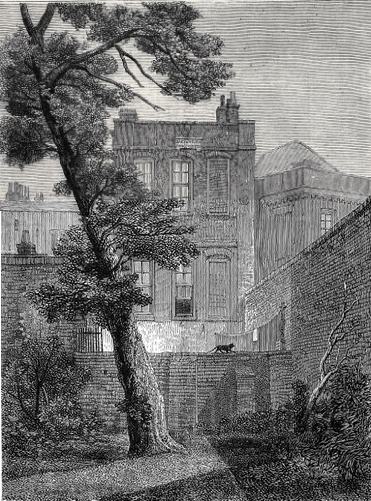

James Mill married Harriet Burrow. Their eldest son, John Stuart Mill, who would later become an immensely influential philosopher and colonial administrator at the East India Company, was born in 1806 in Pentonville, where they had settled.

9. Death

James Mill passed away on June 23, 1836, at the age of 63. He died in London, England, concluding a life marked by significant intellectual contributions and public service.

10. Legacy and Evaluation

James Mill left a lasting impact on philosophy, economics, and politics, shaping intellectual discourse in the early 19th century and influencing subsequent generations of thinkers. His work has been subject to both recognition for its systematic rigor and intense criticism for its colonial biases.

10.1. Positive Contributions

Mill is recognized for his significant contributions to utilitarianism, vigorously advocating and systematizing the principles laid out by Jeremy Bentham. He was a driving force behind the Philosophical Radicals, a movement that championed crucial political and social reforms, including the expansion of the franchise, which culminated in the Reform Bill. His economic theories, particularly his discussions on population growth, the labor theory of value, and the concept of "unearned increment," placed him firmly within the Ricardian school of economics. In psychology, his Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind is lauded for its systematic application of associationism and its rigorous attempt at precise definitions and clear doctrines, marking a new beginning in empirical psychology and influencing later thinkers like Franz Brentano.

10.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his intellectual achievements, James Mill's work has attracted substantial criticism, particularly concerning his views on India and his historical methodology. His History of British India is widely condemned as a prime example of Eurocentric and imperialist historical writing. Critics highlight that Mill, never having visited India and lacking knowledge of its languages, relied solely on English documents, leading to a biased and often derogatory portrayal of Indian society and culture. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen and scholar Thomas Trautmann have sharply criticized his work for its "British Indophobia" and "hostility to Orientalism," noting his descriptions of Indians as inherently deceitful, mendacious, and inferior. Max Müller also argued against Mill's opinion of Indians as an 'inferior race,' stating that such views were responsible for 'some of the greatest misfortunes' that had befallen India.

Furthermore, his economic theories, particularly those related to population and capital growth, have largely been discarded by later economists. In philosophy, while his systematic approach was praised, some of his attempts to reduce complex emotional states to simple pleasurable or painful sensations faced limitations. His critical stance on the Church and religious skepticism, as expressed in "The Church and its Reform," also sparked controversy during his time. Overall, his legacy remains a complex mix of pioneering intellectual contributions and deeply problematic colonial viewpoints.