1. Overview

Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester, born on 3 October 1390 and dying on 23 February 1447, was an English prince, soldier, and significant literary patron during the Hundred Years' War. As the fourth and youngest son of Henry IV of England, brother of Henry V of England, and uncle of Henry VI of England, he styled himself "son, brother and uncle of kings." Despite being characterized by some as reckless, unprincipled, and fractious, he was also celebrated for his intellectual pursuits and is recognized as England's first major patron of humanism in the context of the Renaissance.

Unlike his elder brothers who engaged in military campaigns, Humphrey received an intellectual upbringing, possibly at Balliol College, Oxford. He was created Duke of Gloucester and Earl of Pembroke in 1414 and later served as Lord Protector of England during his nephew Henry VI's minority from 1422 to 1429. His political career was marked by constant quarrels with influential figures like his brother John, Duke of Bedford and his half-uncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort. His impulsive actions, such as his intervention in the Low Countries over his first wife's territorial claims, strained crucial alliances, particularly with Philip III, Duke of Burgundy.

Despite his political missteps and an unfortunate life marked by rash actions, Humphrey was consistently popular with the citizens of London and the Commons, partly due to his advocacy for a spirited foreign policy and his promotion of tax exemptions for English merchants. His deep engagement with scholarship and the arts earned him a widespread reputation as a patron of learning and a benefactor to the University of Oxford, where his donated book collection formed the foundation of what is now Duke Humfrey's Library within the Bodleian Library. This cultural patronage, alongside his popular appeal, led to him being affectionately known as "Good Duke Humphrey" (善良公ZenryōkōJapanese). His political influence waned following defeats in France and the scandalous trial of his second wife, Eleanor Cobham, for witchcraft in 1441. He was arrested on charges of treason in 1447 and died a few days later under suspicious circumstances.

2. Childhood and early career

Humphrey was born on 3 October 1390, though his exact birthplace remains unknown. He was named after his maternal grandfather, Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford. He was the youngest of four brothers, who maintained a close bond; on 20 March 1413, Humphrey and his brother Henry were at their dying father's bedside. All four brothers, Thomas, John, and Humphrey, were knighted in 1399 and joined the Order of the Garter together in 1400.

During the reign of his father, Henry IV, Humphrey received a scholar's education, reportedly at Balliol College, Oxford. This intellectual upbringing contrasted with his elder brothers, who were actively engaged in military campaigns on the Welsh and Scottish borders. Following his father's death, Humphrey's standing within the English nobility was formally recognized. In 1414, he was created Duke of Gloucester and Earl of Pembroke, and was also appointed Chamberlain of England. He subsequently took his seat in Parliament and became a member of the Privy Council of England in 1415.

3. Diplomatic and military career

Humphrey of Lancaster played an active role in England's military campaigns during the Hundred Years' War in France, joining his brother Henry V. Before embarking on the French campaign, while the army was camped at Southampton, Humphrey and his brother, the Duke of Clarence, led an Inquiry of Lords. On 5 August, they presided over the trial of Richard, Earl of Cambridge, and Henry Scrope, who were accused of high treason in the Southampton Plot, an assassination attempt against the king.

During the French campaigns, Humphrey earned a reputation as a capable commander. His classical studies had provided him with knowledge of siege warfare, which proved instrumental in the fall of Honfleur. He participated in the pivotal Battle of Agincourt in 1415, where he was wounded. During the battle, King Henry V personally sheltered him and withstood a determined assault from French knights, protecting his fallen brother. For his services, Humphrey was granted several important offices, including Constable of Dover and Warden of the Cinque Ports on 27 November, as well as King's Lieutenant. His early tenure in government was characterized by peace and success.

This period also saw the unique visit of Emperor Sigismund, the only medieval emperor to visit England. According to Holinshed's Chronicles, Humphrey was a central figure in a symbolic ceremony on 1 May 1416. He greeted the emperor on the shoreline with a sword in hand, "extorting" from Sigismund the renunciation of his prerogatives of dominion over the King of England before allowing him to land. While this story may be apocryphal, it suggests that significant negotiations preceded the emperor's arrival. The Treaty of "eternal friendship", signed on 15 August 1416, ultimately served to anticipate renewed hostilities with France.

Following the death of his brother Henry V in 1422, Humphrey became Lord Protector to his infant nephew, Henry VI. He also asserted his right to the regency of England after the death of his elder brother, John, Duke of Bedford, in 1435. However, his claims were strongly contested by the lords of the king's council, particularly his half-uncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort. Though Henry V's will, rediscovered at Eton College in 1978, actually supported Humphrey's claims, his political ambitions were often thwarted.

Humphrey's diplomatic and military career was also marked by a significant and controversial intervention in the Low Countries. In October 1424, he invaded the region, asserting the rights of his wife, Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut and Holland, to her ancestral lands. This action brought him into direct conflict with Philip III, Duke of Burgundy (フィリップ3世Firippu SanseiJapanese), a crucial English ally at the time. This unilateral move, undertaken without the full consent of the English council, threatened to destabilize the Anglo-Burgundian alliance. Despite his brother's strong admonitions, Humphrey persisted, leading to his defeat and return to England in April 1425. He dispatched another expedition in December 1425, which was again defeated by Burgundian forces. Ultimately, he was compelled to abandon his intervention in the Low Countries after Pope Martin V annulled his marriage to Jacqueline in 1428.

In 1436, Philip, Duke of Burgundy, attacked Calais. Duke Humphrey was appointed garrison commander and faced an assault from the landward side by the Flemings. Despite stubborn English resistance, Humphrey eventually marched his army to Baillieul, ensuring their safety. He then threatened St. Omer before sailing back to England.

4. Political career and Regency

Humphrey's political career was largely defined by his role as Lord Protector of England during the minority of his nephew, Henry VI, which began after Henry V's death in 1422. Although he claimed the right to the regency, the advisory council assisting the young king decided to significantly limit Humphrey's power. His elder brother, John, Duke of Bedford, was designated as the primary regent, with Humphrey serving merely as his deputy in England during John's absence in France. Furthermore, Humphrey's involvement in policy required the consent of the advisory council, a major restriction on his authority.

This arrangement led to a deep and lasting conflict between Humphrey and his half-uncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort (ヘンリー・ボーフォートHenrī BōfōtoJapanese), who had played a significant role in limiting Humphrey's power. Humphrey consistently sought to undermine Beaufort's influence, attempting to remove him and his supporters from positions of power through various accusations and dismissals. However, these efforts were routinely thwarted by the opposition of the council. The rivalry between the two became so intense that in 1426, the Parliament of Bats (バット議会Batto GikaiJapanese) was convened to mediate their dispute, though the truce was temporary.

Humphrey's impulsive actions extended to foreign policy. His invasion of the Low Countries in 1424, driven by his first wife Jacqueline's territorial claims, directly challenged the interests of Philip III, Duke of Burgundy, a crucial ally for England in the Hundred Years' War. This unilateral action nearly shattered the Anglo-Burgundian alliance, drawing strong condemnation from his brother, the Duke of Bedford. Despite initial defeats, Humphrey continued his efforts in the Low Countries until his marriage to Jacqueline was annulled by the Pope in 1428, forcing him to abandon his claims.

After John, Duke of Bedford's death in 1435, and Henry VI's declaration of personal rule in 1437, the Beaufort faction, which enjoyed the king's strong trust, solidified its control over England. Defeated in this political struggle, Humphrey became a staunch opponent of concessions in the French conflict and a vocal proponent of offensive warfare. He allied with figures like Richard, Duke of York, forming an anti-war faction that stood in direct opposition to the peace-oriented policies advocated by the Beaufort faction.

As the peace faction increasingly surrounded Henry VI, Humphrey found himself isolated. In 1440, he vehemently opposed the release of the captive Charles of Orléans, a move orchestrated by the peace faction to advance negotiations with France, but his objections were overruled. His political influence suffered a devastating blow in 1441 when his second wife, Eleanor Cobham, was arrested and tried on charges of practicing witchcraft against the king. This scandal greatly diminished his standing and forced him to retire from public life.

Throughout his political career, despite his controversial actions and his struggles within the court, Humphrey maintained significant popularity among the citizens of London and the Commons. This popularity stemmed from his advocacy for a spirited foreign policy and his support for English merchants, including promoting tax exemptions. However, his unpopular second marriage to Eleanor Cobham ultimately provided his enemies with potent ammunition against him.

5. Patronage of arts and learning

Humphrey of Lancaster was widely recognized for his significant contributions as a patron of learning and the arts, earning him a reputation that transcended his political controversies. He was considered an exemplar for institutions like Eton College and the University of Oxford, embodying the quintessential well-rounded princely character, combining accomplishment, diplomacy, and political cunning with a deep scholarly approach to the burgeoning Renaissance culture.

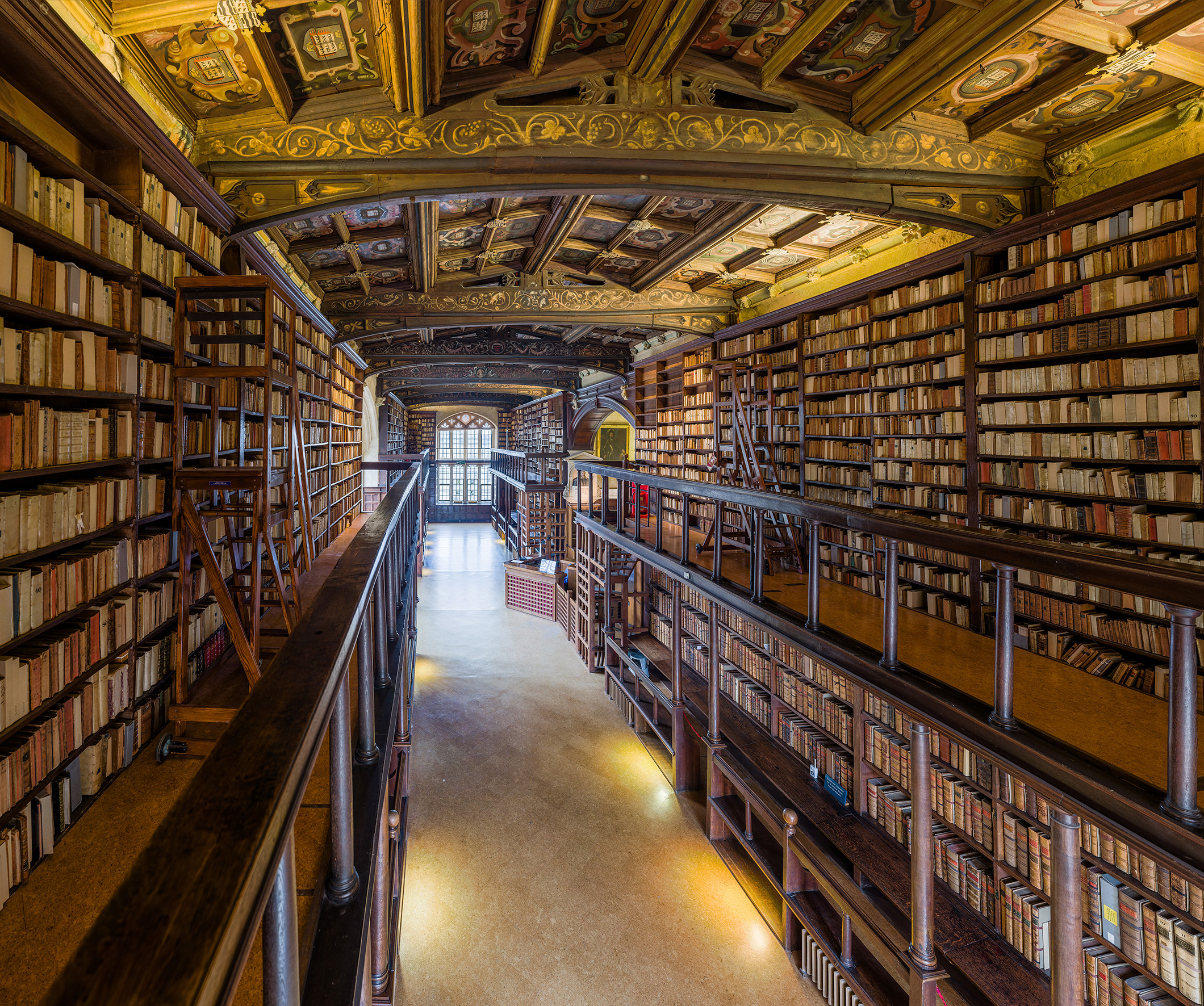

His most enduring legacy in this regard is his profound impact on the University of Oxford. Humphrey donated more than 280 manuscripts to the university, a collection that formed the initial foundation of what is now known as Duke Humfrey's Library, a prominent part of the Bodleian Library. The establishment of such a comprehensive library significantly stimulated new learning and intellectual development within England. His name continues to be honored through Duke Humfrey's Library and in place names such as Duke Humphrey Road on Blackheath, south of Greenwich.

Humphrey was also a notable patron of literature, supporting poets such as John Lydgate and John Capgrave. He actively corresponded with many leading Italian humanists of his time and commissioned numerous translations of Greek classics into Latin, thereby facilitating the spread of classical knowledge in England. His friendship with Zano Castiglione, the Bishop of Bayeux, opened doors to further connections on the Continent, including notable humanists like Leonardo Bruni, Pietro Candido Decembrio, and Tito Livio Frulovisi. Beyond Oxford, he also extended his patronage to the Abbey of St Albans.

In a demonstration of his patronage, Humphrey, along with his second wife Eleanor, commissioned a special drinking goblet known as the Wreathen Cup. This hanap, possibly their wedding cup, was used when they hosted dinners at their Greenwich palace, La Pleasaunce, and their London residence, Baynard's Castle. The Wreathen Cup later came into the possession of his kinswoman, Lady Margaret Beaufort, who bequeathed it to her confessor, Dr. Edmund Wilford of Oriel College, Oxford. He, in turn, exchanged it for another piece of silver that Lady Margaret had left to her foundation at Christ's College, Cambridge, where the cup remains to this day. It is conjectured that the cup reached Lady Margaret through her husband, Thomas Stanley, who had custody of Eleanor during her imprisonment and was involved in liquidating Humphrey's estate.

Humphrey's intellectual activity and his support for a spirited foreign policy made him popular among the literary figures of his age and with the common people, contributing to his popular epithet, "Good Duke Humphrey."

6. Personal life and marriages

Humphrey of Lancaster married twice during his lifetime but left no surviving legitimate heirs.

6.1. First marriage: Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut and Holland

Around 1423, Humphrey married Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut and Holland (ジャクリーヌ・ド・エノーJakurīnu do EnōJapanese), who died in 1436. Jacqueline was the daughter of William VI, Count of Hainaut. Through this marriage, Humphrey assumed the titles of "Count of Holland, Zeeland, and Hainault." This union, however, became a source of significant political conflict. Humphrey briefly engaged in military campaigns to retain these titles when they were contested by Jacqueline's cousin, Philip the Good (see: War of Succession in Holland). The couple had a stillborn child in 1424. The marriage was eventually annulled in 1428 by Pope Martin V, who declared Jacqueline's prior marriage to John IV, Duke of Brabant valid, effectively disinheriting Jacqueline from her lands.

6.2. Second marriage: Eleanor Cobham

In 1428, following the annulment of his first marriage, Humphrey married Eleanor Cobham, who had previously been his mistress and served as a lady-in-waiting to Jacqueline. This marriage proved to be a major factor in Humphrey's political downfall. In 1441, Eleanor was tried and convicted of practicing witchcraft against King Henry VI, in what was perceived as an attempt to maintain or gain power for her husband. She was condemned to public penance, followed by exile and life imprisonment, and remained incarcerated until her death in 1452. This marriage produced no legitimate children.

6.3. Children

Humphrey had two illegitimate children by unknown mistresses. It is possible that Eleanor Cobham was the mother of one or both of these children before her marriage to Humphrey. Due to their illegitimacy, they were unable to succeed to their father's titles. His illegitimate children were:

- Arthur Plantagenet (アーサーĀsāJapanese) (died after 1447). He was arrested for treason five months after his father's death.

- Antigone Plantagenet (アンティゴネAntigoneJapanese), who first married Henry Grey, 2nd Earl of Tankerville, Lord of Powys (circa 1419-1450), and later married John d'Amancier.

7. Downfall and death

The events leading to Humphrey's political downfall began with the increasing unpopularity of his marriage to Eleanor Cobham, which provided ample ammunition for his political enemies. In 1441, Eleanor was arrested and subsequently tried and convicted on serious charges of sorcery and heresy, accused of using black magic against King Henry VI. This scandal severely damaged Humphrey's reputation and political standing, leading him to retire from public life.

His political isolation deepened as the peace faction, led by figures such as Queen Margaret of Anjou, Cardinal Henry Beaufort, and William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk (ウィリアム・ド・ラ・ポールWiriamu do Ra PōruJapanese), gained ascendancy around Henry VI. Humphrey, a staunch advocate for continued aggressive warfare in France, found himself increasingly at odds with the prevailing political climate that favored peace negotiations.

On 20 February 1447, Humphrey was arrested on charges of treason at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. Just three days later, on 23 February 1447, he died while under arrest. The circumstances of his death were suspicious, leading to contemporary interpretations and widespread suspicions that he had been assassinated by his political rivals, particularly the peace faction. However, it is also considered probable that he died of a stroke. He was buried at St Albans Abbey, adjacent to St Alban's shrine. Following Humphrey's death, Cardinal Beaufort also died in April of the same year, and political power largely consolidated around William de la Pole. Humphrey's illegitimate son, Arthur, was also arrested for treason five months after his father's death.

8. Legacy and evaluation

Humphrey of Lancaster left a multifaceted legacy, particularly in English society and culture. Despite his controversial political career and eventual downfall, his reputation was largely restored by the end of the 15th century, with petitions made to Parliament each year for the rehabilitation of "Good Duke Humphrey."

His most significant and enduring impact was as a patron of arts and learning. His name lives on prominently in Duke Humfrey's Library, a part of the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, which was founded on his substantial donation of over 280 manuscripts. This collection greatly stimulated new scholarship and learning in England. He was also a patron of literary figures such as the poet John Lydgate and John Capgrave, and actively corresponded with leading Italian humanists, commissioning translations of Greek classics into Latin.

In terms of architectural contributions, after inheriting the manor of Greenwich, Humphrey enclosed Greenwich Park and, from 1428, oversaw the construction of a palace on the banks of the River Thames, initially known as Bella Court and later as the Palace of Placentia or La Pleasaunce. The Duke Humphrey Tower, which once surmounted Greenwich Park, was demolished in the 1660s, and its site was subsequently chosen for the construction of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

Humphrey's popular image as "Good Duke Humphrey" (善良公ZenryōkōJapanese) stemmed from his scholarly activities, his advocacy for a spirited foreign policy, and his popularity among London citizens and merchants, for whom he promoted tax exemptions. This popular perception contributed to phrases that entered the English lexicon. "Duke Humphrey's Walk" was the name given to an aisle in Old St Paul's Cathedral that was popularly, though mistakenly, believed to contain his tomb (it was actually a monument to John Lord Beauchamp de Warwick, who died in 1360). This area was frequented by the poor, leading to the phrase "to dine with Duke Humphrey," which was used to describe poor people who had no money for a meal. The writer Saki later updated this phrase, referring to a "Duke Humphrey picnic" as one without food, in his short story "The Feast of Nemesis." In reality, Humphrey's actual tomb is located in the Abbey of St Albans (now St Albans Cathedral), which was restored by Hertfordshire Freemasons in 2000 to celebrate the millennium.

8.1. In literature

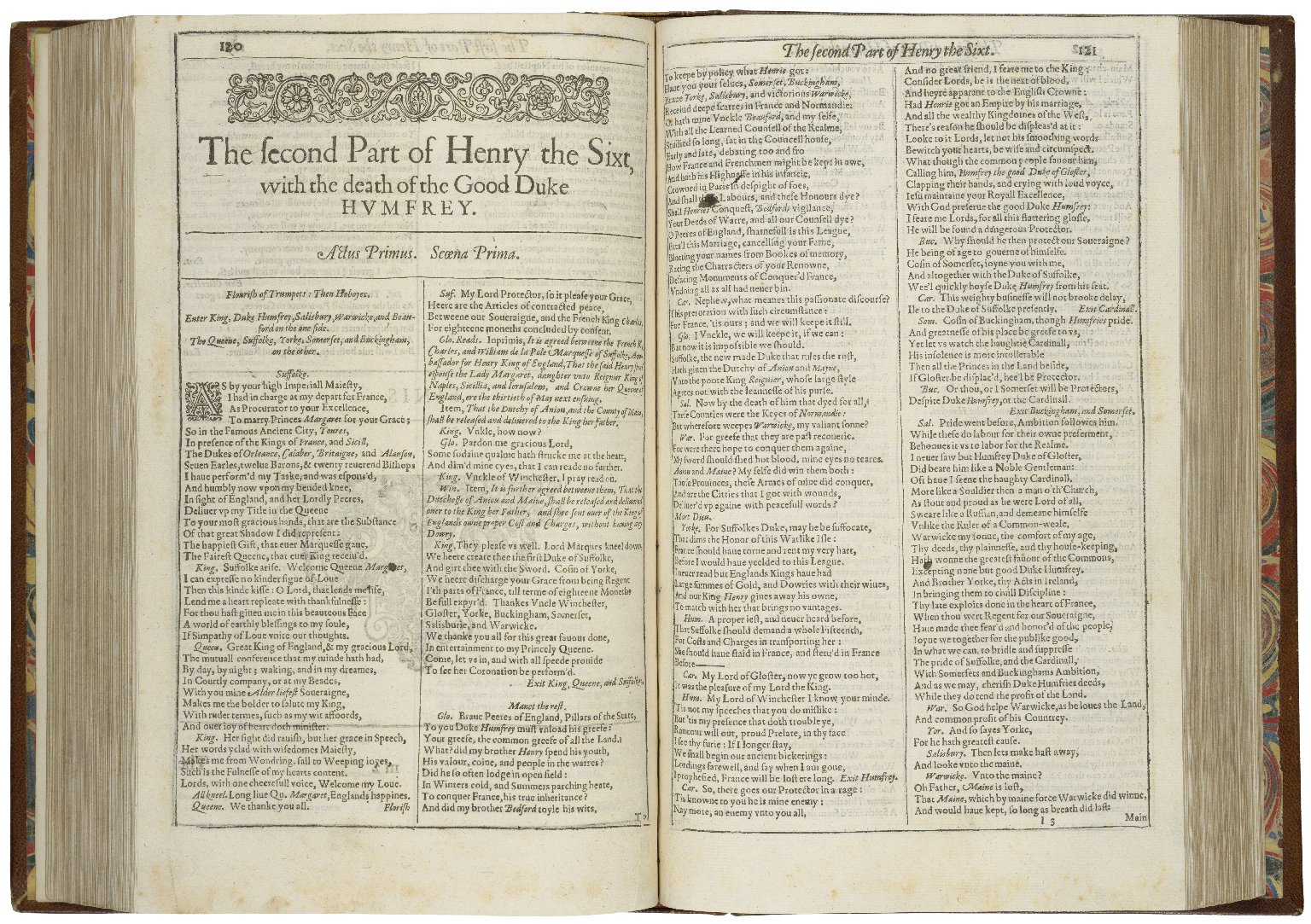

Humphrey of Lancaster's life and character have been depicted in various literary works, most notably in the historical plays of William Shakespeare. In Shakespeare's first historical tetralogy, Humphrey is portrayed as one of the most unambiguously sympathetic characters, presented in a uniformly positive light throughout the plays. He appears as a minor character in Henry IV, Part 2 and Henry V. However, he takes on a major role in Henry VI, Part 1, which dramatizes his conflict with Cardinal Beaufort, and in Henry VI, Part 2, which depicts his disgrace and death following his wife's alleged sorcery. Shakespeare notably portrays Humphrey's death not as a natural event but as a murder, orchestrated by William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk and Queen Margaret of Anjou.

Beyond Shakespeare, Humphrey's life has inspired other dramatic and literary works. The 1723 play Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester by Ambrose Philips centers on his life, with Barton Booth playing the lead role in the original Drury Lane production. More recently, Margaret Frazer's 2003 historical mystery novel, The Bastard's Tale, revolves around the events surrounding Humphrey's arrest and death.

9. Titles, honours and arms

Humphrey of Lancaster held numerous significant titles and offices throughout his life:

- Duke of Gloucester**: Created on 16 May 1414, this was the second creation of this dukedom. The title became extinct upon his death on 23 February 1447.

- Earl of Pembroke**: Created on 16 May 1414, this was the fifth creation of this earldom. The title was subsequently made hereditary, but it defaulted to William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk.

- Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports**: Appointed on 27 November 1415, holding this position until his death on 23 February 1447. He succeeded Thomas Fitzalan, 5th Earl of Arundel and Surrey and was succeeded by James Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele.

- Justice in eyre south of the River Trent**: Appointed on 27 January 1416, holding this role until his death on 23 February 1447. He succeeded Edward, 2nd Duke of York and was succeeded by Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York.

- Lord Protector of England for Henry VI**: Held this office from 5 December 1422 to 6 November 1429, jointly with John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford. This office was a new creation at the time and became vacant after his tenure, later being held by Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York.

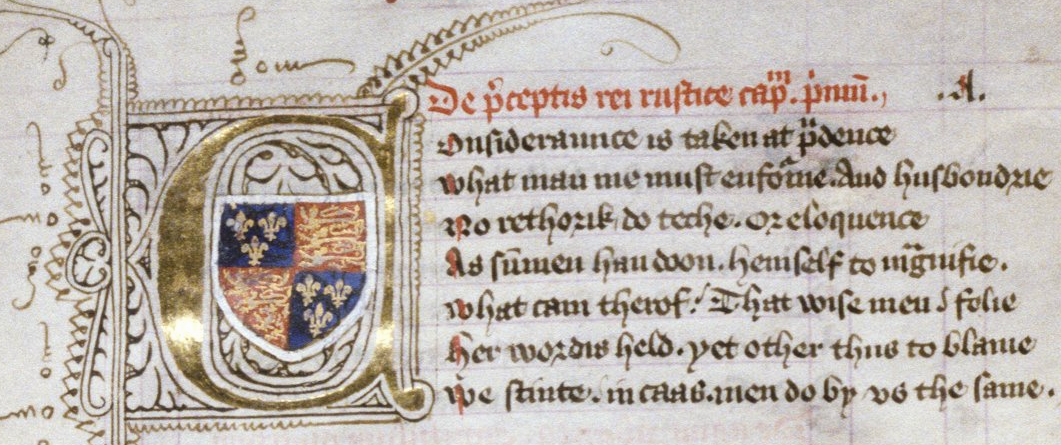

Humphrey's heraldic achievement featured the arms of King Henry IV, which were then differenced by a bordure argent. This design visually represented his direct lineage from the English monarchy, with the bordure indicating his position as a younger son.

10. Ancestry

Humphrey of Lancaster's ancestry reflects his prominent position within the English royal family and his connections to significant noble houses.

- 1. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

- 2. Henry IV of England

- 3. Mary de Bohun

- 4. John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster

- 5. Blanche of Lancaster

- 6. Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford

- 7. Joan Fitzalan

- 8. Edward III of England

- 9. Philippa of Hainault

- 10. Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster

- 11. Isabel of Beaumont

- 12. William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton

- 13. Elizabeth de Badlesmere

- 14. Richard Fitzalan, 10th Earl of Arundel

- 15. Eleanor of Lancaster