1. Overview

Hiraga Gennai was a Japanese polymath and rōnin who lived during the Edo period (1728-1780). He was a multifaceted figure, excelling as a pharmacologist, geologist, Rangaku (Dutch Studies) scholar, physician, industrial entrepreneur, gesaku (satirical literature) writer, jōruri author, haiku poet, Western-style painter, and inventor. Gennai is particularly known for his innovative contributions, including the restoration of the Elekiter (electrostatic generator), the development of the Kandankei (thermometer), and the creation of Kakanpu (asbestos cloth). He also authored numerous literary works, such as the satirical novels Fūryū Shidōken den and Nenashigusa, and essays like On Farting. His work extended to practical guidebooks, including those on male prostitutes in Edo.

Gennai played a significant role in introducing Western knowledge and technology to Japan during a period of national isolation. His efforts in fields like mining, pottery, and the organization of early product exhibitions demonstrated his entrepreneurial spirit and desire for national benefit. Despite his genius and wide-ranging accomplishments, his unconventional lifestyle, including his homosexuality, and the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death in prison, have made him a figure of both admiration and controversy in Japanese history.

2. Name

Hiraga Gennai's birth name was Shiraishi Kunitomo (白石国倫Shiraishi KunitomoJapanese). He was also known by the personal name (諱iminaJapanese) Kunitomo, though a 1934 genealogical diagram also lists Kunimune (国棟KunimuneJapanese), which does not appear in a 1986 version. His common name (通称tsūshōJapanese) was Gennai (源内GennaiJapanese). He temporarily changed the spelling to Gennai (元内GennaiJapanese) when he was re-employed by the Takamatsu Domain, to avoid using the character `源` (Minamoto), which was part of the lord's surname. After his resignation from the domain, he reverted to using the original spelling of Gennai (源内GennaiJapanese). His courtesy name (字azanaJapanese) was Shi'i (士彝Shi'iJapanese), though some sources render it as Zi'i (子彝Zi'iJapanese).

Throughout his career, Gennai used a multitude of pseudonyms and pen names to suit his diverse activities. His most prominent literary pen name was Fūrai Sanjin (風来山人Fūrai SanjinJapanese), meaning "Mountain Man of Wind and Rain." Other notable pen names include Kyūkei (鳩渓KyūkeiJapanese), which is said to have been derived from "Hatodani," a place name in Shido village, his birthplace. He also used Tenjiku Rōnin (天竺浪人Tenjiku RōninJapanese, "Indian Rōnin") and Gotōken (悟道軒GotōkenJapanese). For his jōruri (puppet theater) works, he adopted the name Fukuchi Kigai (福内鬼外Fukuchi KigaiJapanese). His haiku pen name was Rizan (李山RizanJapanese). It is important to note that Tenjiku Rōjin (天竺老人Tenjiku RōjinJapanese), which differs by one character, was a pen name used by his disciple, Morishima Chūryō. In some of his own writings, Gennai created a character modeled after himself named Hinka Zen'nai (貧家銭内Hinka Zen'naiJapanese).

3. Biography

Hiraga Gennai's life was a testament to his insatiable curiosity and innovative spirit, marked by periods of intense study, prolific creation, and ultimately, a tragic end.

3.1. Birth and Family Background

Hiraga Gennai was born in 1729 in the village of Shidoura, located in Sanuki Province, which is part of the modern-day city of Sanuki, Kagawa. He was the third son of Shiraishi Mozaemon (良房), a low-ranking provincial samurai who served the Takamatsu Domain. The Shiraishi clan claimed descent from the Hiraga clan, local warlords in Saku District, Shinano Province. After their defeat by the Takeda clan in 1536 at Uminokuchi Castle, they fled to Mutsu Province, where they served the Date clan and adopted the surname "Shiraishi" from a location in Mutsu. They later accompanied a branch of the Date clan to Uwajima Domain in Shikoku before eventually settling in Takamatsu, where they supplemented their meager samurai income with farming. It is said that Gennai's generation restored the "Hiraga" surname.

3.2. Early Life and Education

Gennai spent his childhood in Takamatsu, where he received an early education in Confucianism and haiku poetry. He also demonstrated an early aptitude for craftsmanship, creating intricate designs on hanging scrolls (掛け軸kakejikuJapanese), including one known as "Omiki Tenjin." His talent led him to begin studies as an herbalist at the age of 13, becoming an apprentice to a physician. At 18, he was offered an official position in the local daimyō's herb garden. In 1749, following his father's death, Gennai became the head of the family and took up the position of a storehouse keeper (蔵番kura-banJapanese) for the domain.

3.3. Studies in Nagasaki

Around 1752, Gennai embarked on a year-long study trip to Nagasaki, which was then one of the only ports open to foreign ships in Japan. Despite his low social status and his duties as a storehouse keeper, the reasons for his extended study in Nagasaki remain somewhat mysterious. Theories suggest he may have had secret support from the Takamatsu Domain lord, Matsudaira Yoriyasu, who was interested in herbalism and natural products, or from a patron like Kubo Sōkan, a physician and herbal enthusiast from Takamatsu. He is also believed to have been employed as an assistant to the domain's official herbalist.

In Nagasaki, Gennai immersed himself in the study of Western medicine, including European pharmaceutical and surgical techniques, and other aspects of Rangaku (Dutch Studies). His interactions with Chinese merchants and members of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) exposed him to new ideas and technologies, including ceramics. After returning from Nagasaki in 1754, Gennai cited "recent illness" as his reason for resigning from his position as storehouse keeper. He then transferred headship of the family to his younger sister's husband, who was adopted into the family. In 1755, he demonstrated his practical skills by creating a distance-measuring device (量程器ryōteikiJapanese) and a magnetic compass (磁針器jishinkiJapanese), which was modeled after a Dutch instrument.

3.4. Life in Edo

After his studies in Nagasaki, Gennai continued his intellectual journey, traveling to Osaka and Kyoto to further his knowledge of herbal medicine under Toda Kyokuzan. In 1757, he moved to Edo (modern-day Tokyo), where he would spend much of his productive life.

3.4.1. Academic and Scientific Pursuits

In Edo, Gennai became a disciple of the prominent herbalist Tamura Ransui. Under Ransui's guidance, Gennai researched and successfully cultivated natural specimens of ginseng, a medicinal herb that had previously been imported. His work made domestic production of ginseng possible in Japan. He also developed an interest in Dutch natural history, actively seeking out Western books. However, lacking strong language skills, he relied on Dutch interpreters to read and explain the texts to him. Some contemporaries, like the Confucian scholar Shibano Ritsuzan, criticized Gennai's command of classical Chinese, remarking that he was "a person without academic knowledge."

Gennai's scientific experiments were diverse, encompassing mineral prospecting and working with static electricity. He made a second trip to Nagasaki to study advanced mining and ore refining techniques.

3.4.2. Inventions and Technological Contributions

Gennai's inventive spirit led to several notable creations. In 1776, he successfully repaired and restored an Elekiter, a static electricity generator of Dutch origin. This device became a popular attraction, and Gennai used it as a high-class showpiece, charging admission and adding entertainment to attract visitors, using the proceeds to support himself.

He also developed the Kandankei (寒熱昇降器KandankeiJapanese, thermometer) in 1765, which, though no longer extant, is believed to have been an alcohol thermometer based on Dutch and French sources. This thermometer used the Fahrenheit scale and included labels for various temperature ranges from "extreme cold" to "extreme heat." Another significant invention was Kakanpu (火浣布KakanpuJapanese, asbestos cloth), a fire-resistant fabric.

Gennai is also credited with teaching children the principles of hot air balloons in Kamihinokinai, Akita Prefecture, which is believed to be the origin of the traditional Kamihinokinai Paper Balloon Festival. He is also popularly, though inaccurately, credited with inventing the taketombo (bamboo-copter), a device that predates him.

Concerned about the outflow of gold and silver from Japan due to the popularity of imported Kingarawashi (gold-embossed leather paper), Gennai invented a Japanese paper imitation, also known as Kingarawashi (金唐革紙KingarawashiJapanese or 擬革紙GikakushiJapanese). He is also famously, though without definitive primary source evidence, associated with the tradition of eating unagi (eel) on Doyō no Ushi no Hi (midsummer day of the ox). Furthermore, Gennai is considered a pioneer in Japanese advertising, having written commercial jingles for toothpaste (Sōsekikō (漱石膏SōsekikōJapanese)) in 1769 and advertising copy for Shimizumochi in 1775, for which he received compensation.

3.4.3. Literary and Artistic Activities

Gennai was a prolific writer, producing a wide range of literary works. He was a pioneer of the gesaku (satirical literature) genre, writing satirical novels in the kokkeibon and dangibon styles. His notable works include Fūryū Shidōken den (1763), Nenashigusa (1763), and Nenashigusa kohen (1768). He also authored satirical essays such as On Farting and A Lousy Journey of Love. The latter was compiled and published posthumously by his friend and trainee, Ōta Nanpo, in the anthology Blown Blossom and Fallen Leaves.

Beyond satire, Gennai wrote guidebooks on the male prostitutes of Edo, including Kiku no en (1764) and San no asa (1768), as well as Danshoku Saiken (1775). As a jōruri author, writing under the pen name Fukuchi Kigai (福内鬼外Fukuchi KigaiJapanese), he produced numerous plays, many in the historical drama (時代物jidaimonoJapanese) style, often incorporating elements of everyday life (世話物sewamonoJapanese). He also wrote controversial erotic works, such as Nagamakura Shitone Kassen (Long Pillow Battle of the Futons), which depicted explicit sexual encounters.

In the realm of art, Gennai was known for his Western-style oil paintings, examples of which include "Red-Clothed Dutchman with a Black Servant" (黒奴を伴う赤服蘭人図Kokudo o Tomonau Akefuku Ranjin-zuJapanese) and "Western Woman" (西洋婦人図Seiyō Fujin-zuJapanese), the latter housed at the Kobe City Museum. He also contributed to the design of pottery, creating the distinctive "Gennai ware" (源内焼Gennai-yakiJapanese). He collaborated with Suzuki Harunobu to organize picture calendar exchange events, which contributed to the rise of ukiyo-e. He is also said to be the author of the famous four-line poem used to explain the concept of kishōtenketsu (plot structure).

3.4.4. Personal Life and Philosophy

Gennai was known for his unconventional and often eccentric personality. He was described as an onna-girai (女嫌いonna-giraiJapanese, "woman-hater") and was openly homosexual, never marrying. He wrote works that celebrated same-sex relationships over heterosexuality and was known to favor and have relationships with Kabuki actors, most notably Segawa Kikunojō II.

His ambition to serve a major domain or the shogunate was thwarted when he resigned from the Takamatsu Domain in 1761, incurring a shikan okamai (仕官お構いshikan okamaiJapanese, prohibition from serving other lords). This meant he could not be employed by any other domain or the shogunate, which some believe fueled a sense of "fury and despair" in his later years, as described by his disciple, the kyōka poet Hiraga Tōsaku. His later life was also marked by worsening economic conditions, leading him to lament, "My achievements are not complete, only my fame has been attained as the year ends."

3.5. Later Life and Death

By the summer of 1779, Gennai had returned to Edo and was undertaking repairs at a daimyō's mansion. The circumstances surrounding his final days are shrouded in mystery and various theories.

The most widely accepted account states that in late 1779, specifically on November 20, Gennai was staying at his residence in Kanda with two disciples, Hisagorō and Jūemon. A "dispute" arose between them in the early morning, during which Gennai drew his sword, injuring both. Hisagorō later died from his wounds. It is said that Gennai had been prone to fits of rage even before this incident. He was subsequently imprisoned on November 21 and died in prison on January 24, 1780, at the age of 52, reportedly from tetanus.

3.5.1. Posthumous Evaluation and Controversy

Following Gennai's death, his friend Sugita Genpaku wished to hold a proper funeral service. However, the shogunate denied permission for reasons that remain unknown. As a result, Genpaku held a memorial service without a body or a tombstone. This unusual circumstance has given rise to numerous theories over the years, including speculation that Gennai did not actually die in prison but was secretly spirited away, possibly with the intervention of Tanuma Okitsugu, a senior official in the Tokugawa shogunate, or even by his former domain, Takamatsu. According to these theories, he might have lived out the rest of his life in obscurity.

Despite the initial prohibition on his funeral, Gennai's legacy was eventually recognized. In 1924, he was posthumously granted the Junior Fifth Rank (従五位jugo'iJapanese). His life and contributions continue to be debated and re-evaluated by historians, with particular attention paid to his role in introducing Western science and his unconventional personal life.

4. Works and Achievements

Hiraga Gennai's contributions spanned an astonishing array of fields, reflecting his polymathic intellect and tireless pursuit of knowledge and innovation.

4.1. Scientific Inventions and Discoveries

Gennai's scientific endeavors led to several significant inventions and advancements:

- Elekiter (Electrostatic Generator): Gennai successfully repaired and restored a Dutch-made electrostatic generator in 1776. While he may not have fully understood its underlying principles, his restoration allowed for its demonstration and study in Japan, sparking interest in Western electrical science. He famously used it as a public spectacle, charging visitors to witness its effects.

- Kandankei (Thermometer): In 1765, Gennai produced Japan's first domestically made thermometer, the "Japanese-made Hot and Cold Ascending/Descending Device" (日本創製寒熱昇降器Nihon Sōsei KandankeiJapanese). Although the original no longer exists, it is believed to have been an alcohol thermometer, likely based on Western designs. It reportedly used the Fahrenheit scale and included descriptive labels for temperature ranges.

- Kakanpu (Asbestos Cloth): Gennai developed and produced fire-resistant asbestos cloth. His work in this area stemmed from his involvement in mining and material science.

- Air Balloon Research: Gennai is said to have taught the principles of hot air balloons to children in Akita Prefecture, which is believed to be the origin of a local traditional festival. While he did not achieve practical flight, his interest in the subject highlights his forward-thinking approach.

- Kingarawashi (Imitation Leather Paper): To counter the outflow of precious metals caused by the popularity of imported gold-embossed leather, Gennai invented a domestically produced imitation using Japanese paper.

4.2. Industrial and Craft Activities

Gennai actively engaged in various industrial and craft ventures:

- Mineral Prospecting and Mining Development: He discovered iron deposits in Izu Province in 1761 and acted as a broker to establish mining operations. From 1766, he assisted the Kawagoe Domain in developing an asbestos mine in what is now Chichibu, Saitama. He also provided guidance on charcoal production and river transport improvements in the Chichibu region. In 1773, he was invited by Satake Yoshiatsu, the lord of the Kubota Domain, to teach mining engineering at the Ani Mine in Dewa Province.

- Pottery Making (Gennai Ware): In 1772, Gennai discovered a new source of clay in Nagasaki. He petitioned the government to allow large-scale pottery manufacturing for both export and domestic use, stating, "If the Japanese ware is good, then naturally we will not spend our gold and silver on the foreign commodity. Rather to the contrary: since both the Chinese and Hollanders will come to seek out these wares and carry them home, this will be of everlasting national benefit. Since it is originally clay, no matter how much pottery we send out, there need be no anxiety about a depletion of resources." The pottery produced under his guidance, known as "Gennai ware," is distinctive for its brilliant, often three-color, enamels, influenced by the Kōchi ware style from his native Shikoku.

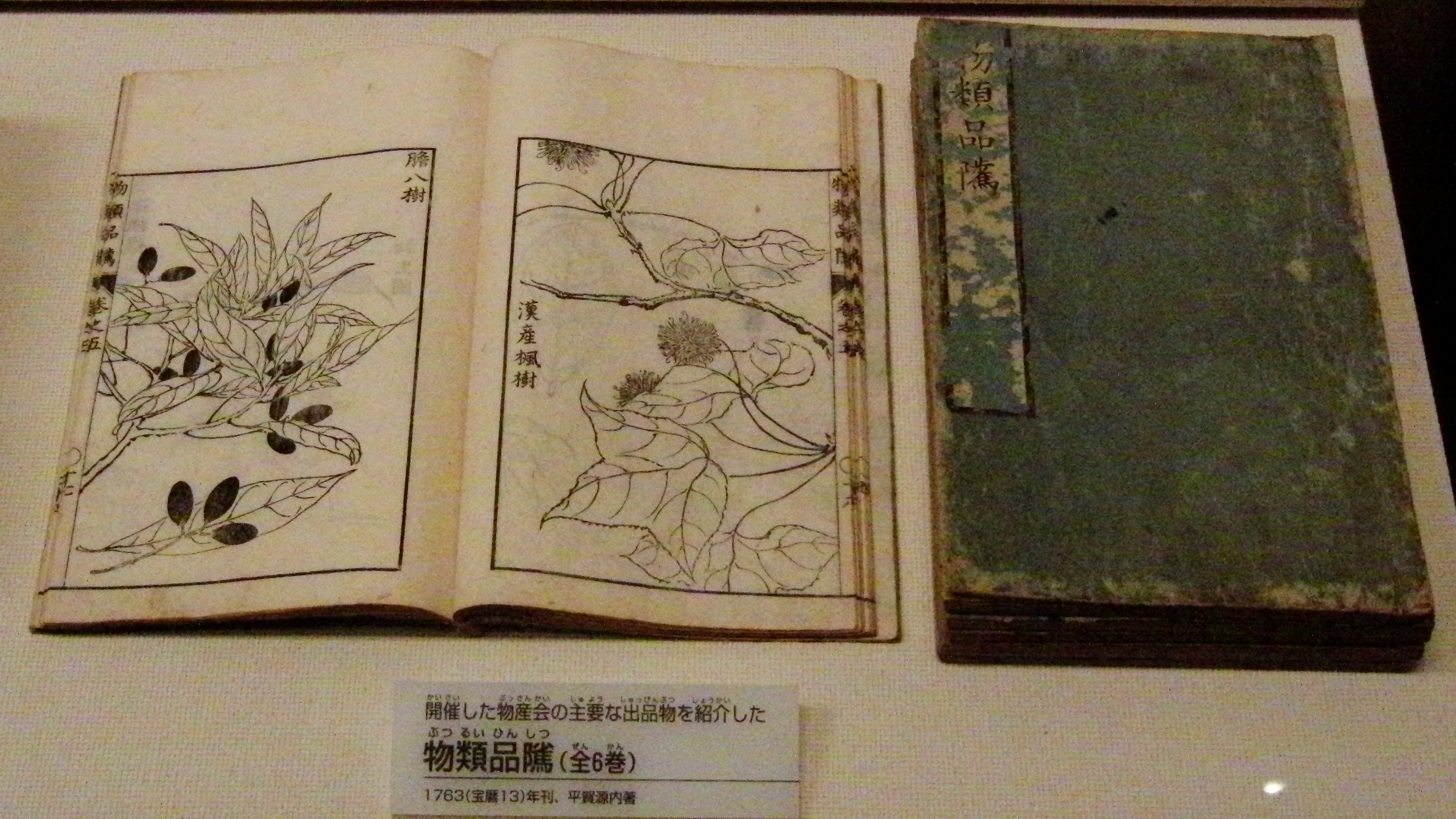

- Exhibitions and Trade Fairs: Gennai was instrumental in organizing Japan's first product exhibitions (薬品会yakuhinkaiJapanese), starting with the "Eastern Capital Products Exhibition" (東都薬品会Tōto YakuhinkaiJapanese) in Yushima, Edo, in 1757. These events showcased various natural products and medicinal herbs, promoting domestic industries.

- Commercial Advertising: Gennai is considered a pioneer in Japanese advertising, having written promotional materials for products such as a toothpaste called Sōsekikō (漱石膏SōsekikōJapanese) in 1769 and Shimizu mochi in 1775. He also has a popular, though unsubstantiated, association with the practice of eating eel on Doyō no Ushi no Hi to combat summer heat.

4.3. Literary Works

Gennai was a prolific and influential writer, particularly in the genre of gesaku (satirical literature).

- On Farting (放屁論HōhironJapanese): This satirical essay explores the interplay between high and low culture in Ryōgoku, a popular entertainment district in Edo. It features Gennai himself debating a Confucian samurai about a peasant who gained fame as a "fart-ist." Gennai argues for the uniqueness and creativity of the act, while the samurai condemns it as a breach of Confucian etiquette. Through this dialogue, Gennai critiques the rigid categorization of art and performance as either "high" or "low."

- Rootless Grass (根南志具佐NenashigusaJapanese): Published in 1763, this satirical work depicts Enma, the King of Hell, falling in love with an onnagata (male actor playing female roles). The story follows the Dragon King's attempts to retrieve the actor from the mortal world, involving a kappa who falls in love with the actor. The narrative culminates in the revelation that the entire story was a dream, foretelling the actor's death. A sequel, Nenashigusa kohen, was published in 1769.

- A Lousy Journey of Love (痿陰隠逸伝Naemara In'itsudenJapanese): This piece, part of a posthumously compiled anthology, follows the journey of two lice traversing a boy's body. Gennai employs extensive wordplay and puns to create an absurd and humorous narrative from the perspective of a louse.

- Fūryū Shidōken den (風流志道軒伝Fūryū Shidōken denJapanese): Published in 1763, this kokkeibon (humorous book) features the storyteller Fukai Shidōken as its protagonist.

- Fūrai Rokubushū (風来六部集Fūrai RokubushūJapanese): A collection of satirical writings, including "On Farting" and "A Lousy Journey of Love."

- Nagamakura Shitone Kassen (長枕褥合戦Nagamakura Shitone KassenJapanese): An erotic work depicting a mass sexual encounter, highlighting Gennai's unconventional literary themes.

- Guidebooks on Male Prostitutes: Gennai authored works like Kiku no en (1764) and Danshoku Saiken (1775), which served as guides to male prostitutes and male brothels in Edo.

- Jōruri Plays: Under the pen name Fukuchi Kigai (福内鬼外Fukuchi KigaiJapanese), Gennai wrote numerous plays for puppet theater, including Shinrei Yaguchinowatari (神霊矢口渡Shinrei YaguchinowatariJapanese, 1770), Genji Ōzōshi (源氏大草紙Genji ŌzōshiJapanese, 1770), Yumuse Chiyū Minato (弓勢智勇湊Yumuse Chiyū MinatoJapanese, 1771), Nen'yō Aioi Genji (嫩榕葉相生源氏Nen'yō Aioi GenjiJapanese, 1773), Mae Taiheiki Koseki Kagami (前太平記古跡鑑Mae Taiheiki Koseki KagamiJapanese, 1774), Chūshin Iroha Jikki (忠臣伊呂波実記Chūshin Iroha JikkiJapanese, 1775), Arago Mitama Nitta Shintoku (荒御霊新田新徳Arago Mitama Nitta ShintokuJapanese, 1779), and Reigen Miyatogawa (霊験宮戸川Reigen MiyatogawaJapanese, 1780).

4.4. Artistic Works

Gennai's artistic talents were as varied as his scientific pursuits.

- Painting: He was a pioneer in Western-style oil painting in Japan, teaching the technique to Odano Naotake, who would later illustrate Kaitai Shinsho. Notable paintings attributed to Gennai include "Red-Clothed Dutchman with a Black Servant" (黒奴を伴う赤服蘭人図Kokudo o Tomonau Akefuku Ranjin-zuJapanese) and "Western Woman" (西洋婦人図Seiyō Fujin-zuJapanese), the latter housed at the Kobe City Museum.

- Pottery: Gennai's influence on pottery is evident in "Gennai ware" (源内焼Gennai-yakiJapanese), a distinctive style characterized by its vibrant, often three-color, enamels, inspired by the Kōchi ware of his home region.

5. Personality and Evaluation

Hiraga Gennai is remembered as a figure of extraordinary intellect and a complex personality, whose life and work continue to invite diverse interpretations.

5.1. Genius and Eccentricity

Gennai was widely regarded as a genius and an eccentric. His polymathic talents allowed him to engage deeply with fields as diverse as natural history, medicine, engineering, literature, and art. He possessed an innovative spirit, constantly seeking to introduce new ideas and technologies from the West to Japan, despite the prevailing policy of national isolation.

His personal life was unconventional for his time. He was known to be onna-girai (女嫌いonna-giraiJapanese, averse to women) and was openly homosexual, never marrying. His relationships with Kabuki actors, particularly Segawa Kikunojō II, were well-known. These aspects of his life, along with his often satirical and provocative writings, contributed to his reputation as an eccentric figure who challenged societal norms.

5.2. Influence and Legacy

Gennai's lasting impact on Japanese society is profound. He was a crucial figure in the development of Rangaku (Dutch Studies), playing a significant role in introducing Western science, technology, and culture to Japan. His efforts in cultivating ginseng, developing asbestos cloth, and restoring the Elekiter laid groundwork for future scientific and industrial advancements.

In literature, he is considered a founder of the gesaku genre, which paved the way for new forms of popular fiction. His satirical works provided sharp social commentary and explored themes that were often taboo. His artistic contributions, particularly in Western-style painting and pottery, also left a distinct mark.

Gennai's influence extended to prominent scholars of his time, including Sugita Genpaku and Nakagawa Jun'an, who were leading figures in Rangaku. Genpaku's memoir, Rangaku Kotohajime, dedicates a chapter to his interactions with Gennai, highlighting the latter's intellectual prowess and influence.

5.3. Criticism and Controversy

Despite his many achievements, Gennai's work and life were not without criticism and controversy. Some historians note that many of his inventions, while ingenious, did not always lead to practical or widespread applications. His later years were marked by financial difficulties and a sense of "fury and despair," as described by his disciple.

The circumstances of his death in prison, following the killing of two carpenters, remain a subject of debate. While the official account attributes his death to tetanus after a drunken rage, alternative theories suggest he may have been secretly spirited away by influential figures like Tanuma Okitsugu or his home domain, living out his life in obscurity. This enduring mystery adds to the controversial aspects of his biography. His satirical writings, particularly those on sexuality and social norms, were also seen as provocative and challenged the conservative values of the Edo period.

6. Grave and Commemoration

Hiraga Gennai's legacy is honored through several graves and commemorative efforts across Japan.

6.1. Tokyo Grave

Gennai's primary grave is located at the former site of Sosen-ji temple in Asakusabashi (now Hashiba, Taitō-ku, Tokyo). Although Sosen-ji temple itself relocated to Itabashi in 1928, the cemetery, including Gennai's grave, remained at its original location. It is said that his friend, Sugita Genpaku, personally funded the construction of this grave. The grave bears the posthumous Buddhist name (戒名kaimyōJapanese) Chiken Rei'yū (智見霊雄Chiken Rei'yūJapanese). Behind Gennai's grave lies the grave of Fukusuke, his long-time manservant. Next to Gennai's tombstone stands a stone monument inscribed with an epitaph composed by Sugita Genpaku.

The grave site has undergone changes over time. Early 19th-century accounts suggest the tombstone initially only bore his posthumous name, with "Hiraga Gennai's Grave" written in ink rather than carved. By 1891, his name and death date were carved into the stone. The surface of the tombstone also shows signs of being unnaturally shaved. In 1931, the tomb was reconstructed under the patronage of Count Matsudaira Yorinaga. The site was provisionally designated a historic site by Tokyo Prefecture in 1924 and again in 1929, after plans to relocate Sosen-ji threatened its preservation. In 1943, it received protection as a National Historic Site. The grave is located about a 12-minute walk from Minami-Senju Station on the Hibiya Line, but it is not open to the public.

6.2. Sanuki Grave

In addition to the Tokyo grave, Hiraga Gennai has a second grave at Jiseiin temple (自性院JiseiinJapanese), the Hiraga family's ancestral temple (菩提寺bodaijiJapanese), in Sanuki, Kagawa, his hometown. This grave is believed to have been erected by Hiraga Gondayū, Gennai's brother-in-law and successor to the Hiraga family, to allow family and local acquaintances to mourn him. An annual memorial service is held here every December.

6.3. Sugita Genpaku's Epitaph

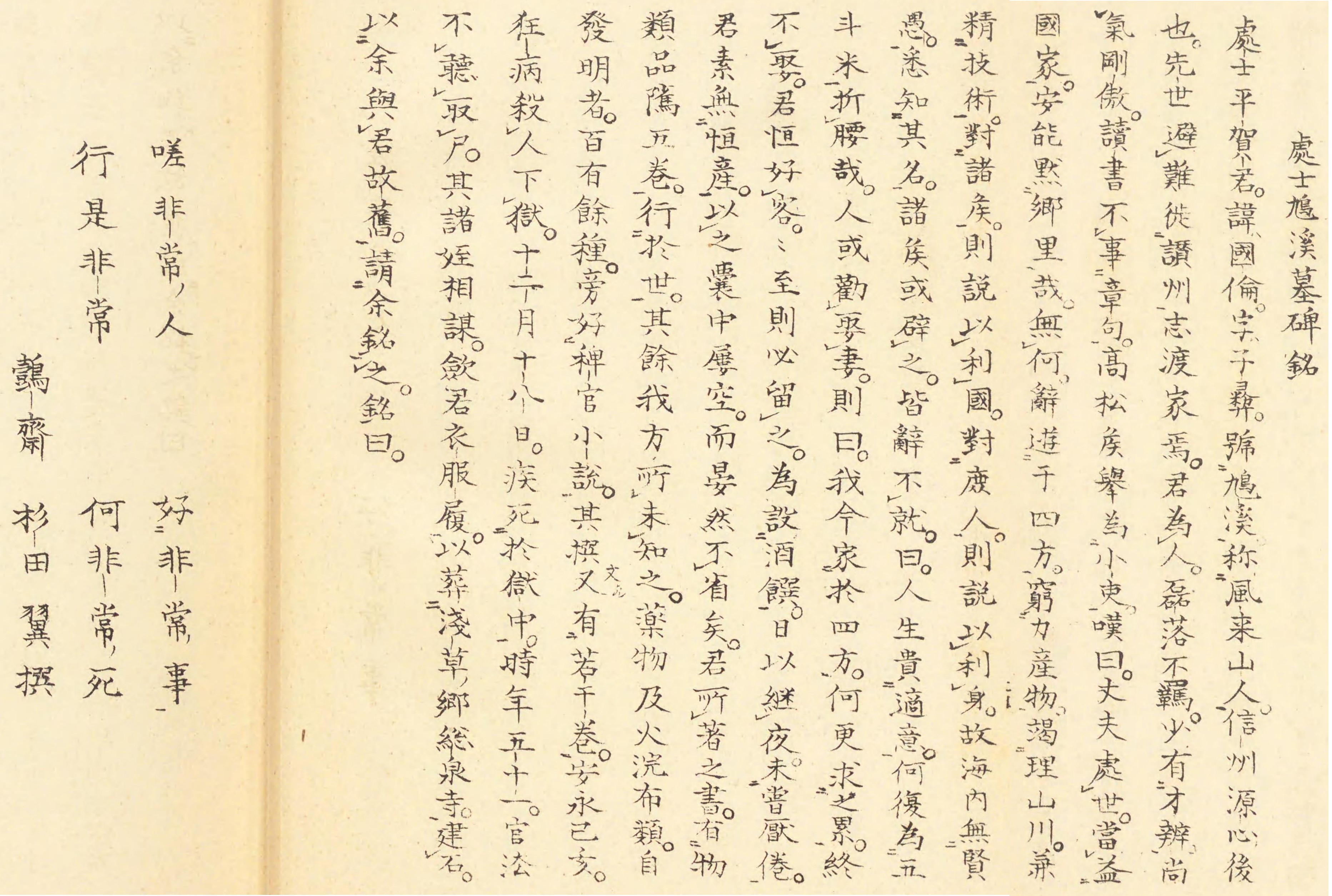

Sugita Genpaku, Gennai's lifelong friend, composed a memorial inscription of about 300 characters titled "Epitaph for Kyūkei, the Unofficial Scholar" (処士鳩渓墓碑銘Shoshi Kyūkei BohimeiJapanese). Genpaku initially envisioned erecting a monument with this inscription at Nōmidō in Kanazawa, Musashi Province (modern-day Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama), though it is unclear if this plan was ever realized.

The full text of the epitaph was preserved through manuscripts, notably the 1845 Gesakushako Hoi (戯作者考補遺Gesakushako HoiJapanese). The epitaph includes a famous 16-character poem that reads:

"嗟非常人 好非常事 行是非常 何非常死Ah, an extraordinary person, who liked extraordinary things, whose actions were extraordinary, why did he die an extraordinary death?Japanese"

(Ah, an extraordinary person, who liked extraordinary things, whose actions were extraordinary, why did he die an extraordinary death?)

There is historical debate about whether this epitaph was ever actually carved onto a tombstone or if it remained a draft. Some theories suggest it was carved but later destroyed or altered due to the prohibition against honoring a criminal's grave. Other scholars argue it was only a manuscript and never physically inscribed. However, in 1930, the full text of the Shoshi Kyūkei Bohimei was indeed carved onto the back of the "Hiraga Gennai Grave Repair Monument" (平賀源内墓地修築之碑Hiraga Gennai Bochi Shūchiku no HiJapanese) erected next to Gennai's grave in Tokyo. The 16-character poem is also inscribed on the pedestal of the Hiraga Gennai statue in Sanuki City.

7. Appearance and Portraits

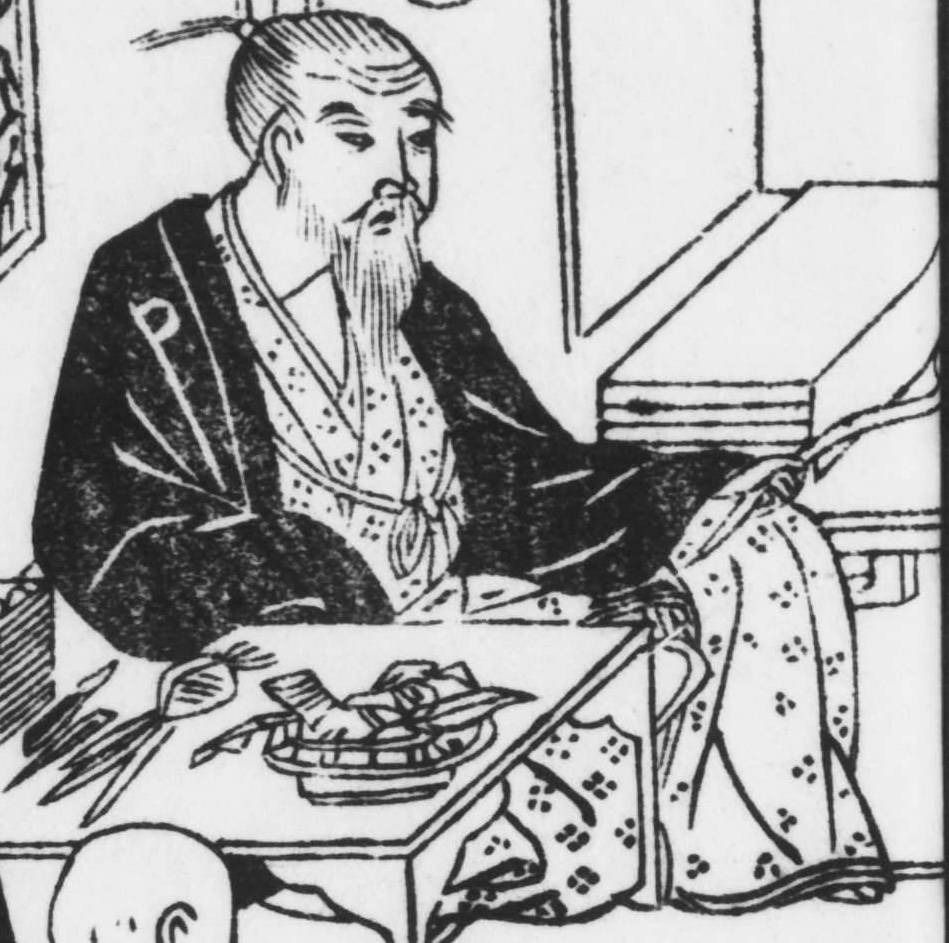

Hiraga Gennai was described as being obese and prone to heat. Various illustrations and portraits exist, some created during his lifetime or shortly after his death, while others are later interpretations.

7.1. 18th-Century Book Illustrations

Some illustrations in Gennai's own published works from the 18th century are believed to depict him. These include illustrations from Tengu Sharekobe Mekiki Engi, and the self-preface and illustrations from Sato no Odamaki Hyō.

7.2. Later Portraits

Later portraits and depictions of Gennai also exist, though their accuracy varies.

7.2.1. Gyoran Sensei Shun'yūki

The illustration "Shun'yūki Hissakuzu" in the book Gyoran Sensei Shun'yūki (published 1781, illustrated by Usui Tōjin) is speculated to depict Ōta Nanpo, Utagawa Enba, and Hiraga Gennai. However, other theories suggest it depicts the book's authors.

7.2.2. Sentetsu Zōden

The "Hiraga Kyūkei Portrait" in the manuscript Sentetsu Zōden Shirinbu Den (compiled 1844 by Hara Tokusai) is said to be based on a painting by either Katsuragawa Hoshū or his younger brother Morishima Chūryō, both of whom knew Gennai. This portrait is considered by some to be a reliable depiction of Gennai.

7.2.3. Gesakushako Hoi

The Gesakushako Hoi (戯作者考補遺Gesakushako HoiJapanese), authored by Kimura Mokuō in 1845, includes an autographed "Hiraga Kyūkei Portrait." This portrait was drawn over 60 years after Gennai's death, based on accounts from elders who knew him. This depiction shows a lean figure, which contrasts with the description of Gennai being obese. The original manuscript of this portrait was lost during World War II, but copies, such as one from the Meiji era housed at Keio University, still exist.

The bronze statue of Hiraga Gennai in Sanuki City was created by sculptor Ogura Uichirō, based on the portrait from Gesakushako Hoi and local legends from Chichibu.

8. Appearances in Popular Culture

Hiraga Gennai's unique life and multifaceted achievements have made him a popular figure in various forms of Japanese and international media.

8.1. Literature and Manga

Gennai has been featured as a character or subject in numerous literary works and manga:

- Hiraga Gennai by Sakurada Tsunehisa (an Akutagawa Prize-winning novel that imagines Gennai's escape from prison with Sugita Genpaku's help).

- Hiraga Gennai by Murakami Motozō.

- Naruto Hichō by Eiji Yoshikawa (Gennai appears in this historical novel).

- Zukkoke Jikan Hyōryūki by Nasu Masamoto.

- Hiraga Gennai Torimonochō by Hisao Jūran.

- Gennai Sensei Funade Iwai by Yamamoto Masayo.

- Burai Bushidō by Nanjo Norio.

- Ibun Fūrai Sanjin by Hirose Tadashi.

- Edo no Ōyamashi Tensai Hatsumeika Hiraga Gennai by Akamatsu Mitsuo (an erotic historical novel).

- Gennai Mangekyō by Shimizu Yoshinori.

- Ōedo Rangaku Koto Hajime by Ōnuma Hiroyuki and Watanabe Jun'ichi.

- Sora Tobu Hyōguya by Yasutaka Tsutsui (Gennai supports Ukita Kōkichi, the first person to fly a manned glider, drawing parallels to modern media culture).

- Ginma Den Gennai Shitō no Maki by Motohiko Izawa.

- Ōedo Kyōryū Den by Baku Yumemakura.

- Moshimo Tokugawa Ieyasu ga Sōri大臣 ni Nattara by Akihito Manabe.

- Nenashigusa Hiraga Gennai no Satsujin by Rokurō Inui.

- Gekijōkoku no Kaijin by Rokurō Inui.

- Ōoku: The Inner Chambers by Fumi Yoshinaga (Gennai is portrayed as a cross-dressing lesbian scholar and inventor).

- Hiraga Gennai Kaikoku Shinsho by Shotaro Ishinomori (Gennai is depicted as the author of Tanuma Okitsugu's biography).

- Haru no Arashi by Kazuo Kamimura.

- Fūunji-tachi by Tarō Minamoto (Gennai is an opinion leader among Rangaku scholars, struggling with the era's inability to keep pace with his genius).

- Edo Murasaki Tokkyū by Nobuyuki Hori (a parody manga where Gennai's "Elekiter" is an electric massager).

- Tōzai Kikkai Shinshiroku by Shigeru Mizuki (Gennai is featured as an eccentric historical figure).

- Onigai Karute Series by Pink Aoya (Gennai appears as a modern-day ghost character).

- Kusari no Kuni by Yukihisa Hoshino (explores a "two Gennai" theory as scientist and gesaku writer brothers).

- Tonegawa Ririka no Jikken-shitsu by Narumi Hasegaki (original story by Aoyagi Aito).

- Isobe Isobee Monogatari by Ryō Nakama.

- Kisōtengai Kabuonkyoku-geki Gennai by Akise Kurosawa and Kensuke Yokouchi.

- Kurogane by Kei Toume (Gennai is the model for Genkichi, a Rangaku scholar who turns the protagonist into a cyborg).

- The light novel Hidan no Aria features Aya Hiraga as a descendant of Gennai.

- Korokoro Soushi by Shintaro Kago features Gennai as a recurring character.

8.2. Film and Television Dramas

Gennai has been portrayed in numerous films and historical dramas:

- Tō, Ima mo Kiezū: Hiraga Gennai (1959, Nippon Television, Gennai: Kōtarō Bandō).

- Tenkagomen (1971, NHK, Gennai: Takashi Yamaguchi) - A satirical drama where Gennai guides viewers through a modern Edo.

- Kikaida 01 (1973, NET Television, Episode 36) - The evil Shadow organization attempts to kidnap Gennai from 1776 to build better robots.

- Naruto Hichō (1977, NHK, Gennai: Takashi Yamaguchi) - Based on Yoshikawa Eiji's novel, features Gennai flying a miniature hot air balloon.

- Utamaro Yume to Shiriseba (1977, Gennai: Ryōhei Uchida) - Appears under the name Fūrai Sanjin.

- Momotarō Samurai (1981, Nippon Television, Episode 226, Gennai: Hiroshi Inuzuka).

- Kage no Gundan II (1981, Kansai Telecasting Corporation, Gennai: Satoshi Yamamura) - Gennai provides scientific assistance to a group of Iga ninja.

- The Hissatsu Series (Asahi Broadcasting Corporation) often anachronistically features Gennai for plots involving modern inventions like hot air balloons.

- Shigotonin Ahen Sensō e Iku (1983, Gennai: Seiji Miyaguchi) - Gennai is depicted as being imprisoned during the Opium Wars, at the age of 113.

- Hissatsu Shikinin (1984, Episode 5) - Gennai serves as a judge in an Edo-period flying contest.

- Fūfu Nezumi Konya ga Shōbu! (1984, TV Tokyo, Gennai: Go Wakabayashi).

- Tonderu! Hiraga Gennai (1989, TBS Television, Gennai: Toshiyuki Nishida) - Gennai acts as a detective, solving mysteries in Edo using his vast knowledge.

- Bīdoro de Sōrō: Nagasakiyume Nikki (1990, NHK, Gennai: Takashi Yamaguchi) - A sequel to Tenkagomen.

- Tonosama Fūraibō Kakuretabi (1994, TV Asahi, Gennai: Shōhei Hino).

- Damashie Utamaro III-IV (2013-2014, TV Asahi, Gennai: Takashi Sasano).

- Ōedo Sōsamō 2015 (2015, TV Tokyo, Gennai: Kenji Kobayashi) - Based on the survival theory, Gennai appears as a guardian for a hidden princess.

- Fūunji-tachi: Rangaku Revolution Hen (2018, NHK General, Gennai: Kōji Yamamoto) - A live-action adaptation of Minamoto Tarō's manga.

- Naruto Hichō (2018, NHK General, Gennai: Bokuzō Masana).

- Nomitori Samurai (2018, Gennai: Shōfukutei Tsurukō).

- Ōedo Steampunk (2020, TV Osaka, Gennai: Seiji Rokkaku).

- Ōoku (2023, NHK General, Gennai: Anne Suzuki) - Based on the manga, portraying Gennai as a cross-dressing woman in a gender-reversed Edo.

- Berabō: Tsutajū Eiga no Yume Banashi (2025, NHK General/BS1, Taiga drama, Gennai: Ken Yasuda) - This marks Gennai's first appearance in an NHK Taiga drama.

- Yume Jūya (2007, Episode 10, Gennai: Kōji Ishizaka).

- Naruto Hichō Zenpen Hondō Hen and Kōhen Naruto Hen (1936-1937, Gennai: Hiroshi Mizuno).

- Shōgi Daimyō (1960, Gennai: Hiroshi Mizuno).

- Maruhi Gokuraku Kurenai Benten (1973, Gennai: Hiroshi Nagahiro).

8.3. Anime and Other Media

Gennai's character has been adapted into various animated series, video games, and stage productions:

- Mask of Zeguy (OVA) - Gennai plays a prominent role in protecting a priestess's descendant and preventing a legendary mask from falling into the wrong hands.

- T.P. Sakura (OVA) - Gennai appears alongside his Elekiter.

- Oh! Edo Rocket (Episode 10) - The retired resident of Fūrai Row-House Block is revealed to be Gennai, a nod to one of his pen names.

- Gintama - Features a mechanic named Hiraga Gengai, modeled after Gennai.

- Zero no Tsukaima - The character Hiraga Saito, hailing from Japan, is speculated to be named after Gennai.

- Read or Die - Gennai appears as a clone of a historical figure, using his Elekiter as a destructive weapon.

- Mai-HiME - A giant mechanical frog is named after him.

- Flint the Time Detective - Gennai appears with the Time Shifter Elekin, which he uses to create giant robots.

- Demashita! Powerpuff Girls Z (Episode 30, "Girls and Him!") - A character named Hiraga Kennai creates a primitive form of Chemical Z and uses an Elekiter to separate a demon's soul from its body.

- Digimon Adventure (Episode 13) - An elderly man named Gennai appears to assist the Chosen Children. He reappears younger in Digimon Adventure 02, with his design and name likely inspired by the historical Gennai.

- Sengoku Collection (Episode 6) - Gennai is embodied as a genius but clumsy girl.

- Carried by the Wind: Tsukikage Ran (Episode 7) - Gennai makes an appearance.

- 21 Emon (Episode 15) - Features a story about Hiraga Gennai staying at a fictional traditional inn in Edo.

- Rakugo Tennyo Oyui (anime) - Gennai is voiced by Terasoma Masaki.

- Anmitsu Hime (anime).

- Soreike! Anpanman - Features an inventor character named Karakuri Gunnai.

- Edo-tan (Capcom video game).

- Sengoku Ace (Psikyo video game) - Features a character named Hirano Gennai.

- Ōedo Renaissance (Victor Interactive Software video game) - A government management game where Gennai's inventions develop Edo.

- Ninkyōden Toseinin Ichidaiki (Genki video game) - Features a mission to escort Gennai.

- Eiketsu Taisen (Sega video game) - Gennai is added as a purple general who deals lightning damage based on his Elekiter.

- Live A Live (Square video game) - A mechanic named Gennai creates mechanical traps in the Bakumatsu chapter, an anachronism for historical mash-up.

- Valkyrie Crusade (mobile card game) - Features a female version of Hiraga Gennai as a card.

- Onigiri (free-to-play MMORPG) - Features a female version of Hiraga Gennai as a main quest character and playable partner.

- Critical Role (web series, Call of Cthulhu one-shot) - Gennai is a member of a secret society, and his Elekiter is used to turn on lights.

- Star Trek: Discovery (Season 3, Episode 9) - A starship named USS Hiraga Gennai is mentioned.

- Ōedo Hyakki Yagyō (大江戸百鬼夜行Ōedo Hyakki YagyōJapanese) (theater) - A musical by Hisashi Inoue, first performed in 1970, known for its extensive research and wordplay.

- Gennai: Naotake o Sodateta Otoko (げんないー直武を育てた男Gennai: Naotake o Sodateta OtokoJapanese) (musical by Warabiza).

9. Related Facilities and Events

Several institutions and events are dedicated to preserving and promoting the legacy of Hiraga Gennai, particularly in his home region.

9.1. Memorial Museums and Institutions

- Hiraga Gennai Memorial Museum (平賀源内記念館Hiraga Gennai KinenkanJapanese) and Hiraga Gennai Sensei Ihinkan (平賀源内先生遺品館Hiraga Gennai Sensei IhinkanJapanese) are located in Shido, Sanuki, Kagawa. These museums showcase Gennai's inventions, literary works, and historical documents, including letters between him and Sugita Genpaku. The Hiraga Gennai Memorial Museum, which opened in 2009, also serves as a venue for the Hiraga Gennai Festival. It is conveniently located about a five-minute walk from Shido Station.

- Hiraga Gennai's Seishi (生祠seishiJapanese, living shrine) is located in Tomonoura, Fukuyama, Hiroshima. This shrine, a Hiroshima Prefectural Historic Site, was erected to honor Gennai during his lifetime, a rare form of tribute for individuals who were still alive.

9.2. Commemorative Events and Awards

- Gennai Award: Established in 1994 through a fund donated by the Elekiter Ozaki Foundation, the Gennai Award is jointly presented by Sanuki City (formerly Shido Town) and the foundation. It recognizes and encourages scientific researchers within the Shikoku region, with awards presented annually in March.

- Hiraga Gennai Festival: Held annually in Sanuki City, this festival commemorates Gennai's life and achievements.

- Hiraga Gennai Exhibitions: Major exhibitions dedicated to Hiraga Gennai have been held across Japan, featuring reconstructed models of his inventions and historical artifacts. Notable exhibitions include those held at the Edo-Tokyo Museum (2003-2004), Tohoku History Museum (2004), Okazaki City Museum of Art (2004), Fukuoka City Museum (2004), and Kagawa Prefectural Museum (2004).