1. Early Life and Family

Wergeland's early life and family connections provided the foundation for his later engagement in national and social issues.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Henrik Wergeland was born on 17 June 1808 in Kristiansand, Norway. He was the eldest son of Nicolai Wergeland (1780-1848), a pastor and politician who was a member of the constituent assembly at Eidsvoll in 1814, a pivotal moment in Norwegian history. Growing up in Eidsvold, where his father served as pastor, placed him at the heart of Norwegian patriotism. His younger sister was the renowned author Camilla Collett, and his younger brother was Major General Joseph Frantz Oscar Wergeland.

Wergeland's paternal ancestry primarily consisted of farmers from Hordaland, Sogn, and Sunnmøre, descendants of a bell-ringer from Sogn. The family name Wergeland is a Danish transliteration of "Verkland," a farm located in Ytre Sogn, at the top of the valley leading from Yndesdalvatnet, north of the county line towards Hordaland. On his mother's side, he had both Danish and Scottish roots. His great-grandfather, Andrew Chrystie (1697-1760), born in Dunbar, Scotland, migrated to Brevik in 1717, then moved to Moss. He married Marjorie Lawrie (1712-1784), also Scottish. Their daughter, Jacobine Chrystie (1746-1818), married Kristiansand town clerk Henrik Arnold Thaulow (1722-1799), who was the father of Wergeland's mother, Alette Thaulow (1780-1843). Wergeland received his first name, Henrik Arnold, from this elder Henrik Arnold.

1.2. Education

In 1825, Henrik Wergeland enrolled at Royal Frederick University (now the University of Oslo) to pursue studies in theology. Beyond his theological education, he also delved broadly into natural and social sciences, a comprehensive intellectual development that significantly shaped his worldview and influenced his later works and activism. He graduated in 1829.

2. Literary Career

Wergeland's literary career was marked by immense productivity and innovation, leaving an indelible mark on Norwegian literature through his poetry, plays, and various other writings.

2.1. Poetry and Major Works

In 1827, Wergeland published his debut collection of poems while still a student. This was followed in 1829 by a volume of lyrical and patriotic poems titled Digte, første Ring (Poems, First Circle), which immediately drew considerable attention to his name. This collection introduced his ideal love, the celestial Stella, often described as Wergeland's equivalent to Beatrice in Dante's Divine Comedy. Stella was a composite character based on four women Wergeland had fallen in love with, though he never achieved a deep relationship with any of them.

The character of Stella also inspired his monumental epic poem, Skabelsen, Mennesket og Messias (Creation, Man and the Messiah), published in 1830. This work was later remodeled in 1845 as Mennesket (Man). In these works, Wergeland explored the history of humanity and God's divine plan for humankind. These poems distinctly exhibit Platonic-romantic ideals, interwoven with principles from the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Through them, Wergeland often criticized the abuse of power, particularly targeting corrupt priests and their manipulation of people's minds. His poetic credo, emphasizing freedom and truth over tyrannical rule and priestly dogma, is famously encapsulated in lines such as:

: Heaven shall no more be split

: after the quadrants of altars,

: the earth no more be sundered and plundered

: by tyrant's sceptres.

: Bloodstained crowns, executioner's steel

: torches of thralldom and pyres of sacrifice

: no more shall gleam over earth.

: Through the gloom of priests, through the thunder of kings,

: the dawn of freedom,

: bright day of truth

: shines over the sky, now the roof of a temple,

: and descends on earth,

: who now turns into an altar

: for brotherly love.

: The spirits of the earth now glow

: in freshened hearts.

: Freedom is the heart of the spirit, Truth the spirit's desire.

: earthly spirits all

: to the soil will fall

: to the eternal call:

:Each in own brow wears his heavenly throne.

:Each in own heart wears his altar and sacrificial vessel.

:Lords are all on earth, priests are all for God.

Other significant narrative poems include Jan van Huysums Blomsterstykke (Flower-piece by Jan van Huysum, 1840), Svalen (The Swallow, 1841), Jøden (The Jew, 1842), Jødinden (The Jewess, 1844), and Den Engelske Lods (The English Pilot, 1844). These works, composed in short lyrical meters, are considered among the most important of their kind in Norwegian literature.

2.2. Plays and Other Writings

Wergeland's contributions extended beyond poetry to include drama, historical essays, and political commentary. His plays, such as Campbellerne (The Campbells, 1837), Søkadetterne (The Sea Cadets, 1837), and Venetianerne (The Venetians, 1843), however, did not achieve lasting theatrical success. Despite this, Campbellerne was a crowd-pleaser and considered his greatest theatrical success due to its immediate appeal. This musical play drew inspiration from tunes and poems by Robert Burns, commenting on Company rule in India and serfdom in Scotland, while also critiquing social conditions in Norway, including poverty and the behavior of avaricious lawyers.

His prose works include important historical essays like Hvi skrider Menneskeheden saa langsomt frem? (Why does humanity progress so slowly?, 1830), in which Wergeland articulated his conviction that divine guidance would lead humanity towards progress and brighter days. Another significant historical work is Norges Constitutions Historie (The History of the Norwegian Constitution, 1841-1843), which remains an important historical source.

Other notable writings from his prolific output include:

- Irreparible Tempus (1828)

- Sinclairs død (1828)

- Digte, Annen Ring (1833)

- Spaniolen (1833)

- Barnemordersken (1835)

- Digte (1838)

- Czaris (1838)

- Stockholmsfareren (1838)

- Engelsk salt (1838)

- Den konstitutionelle (1838)

- Vinægers fjeldeventyr (1838)

- Jødesagen I Det Norske Storthing (1842)

- Hasselnødder (1845)

- Det befriede Europa (1845)

- Kongens ankomst (1845)

2.3. Literary Style and Influences

Wergeland's writing style was distinctive and often revolutionary for his time. Critics, particularly Johan Sebastian Welhaven, initially described his earliest literary efforts as "wild and formless," attributing it to imagination without taste or knowledge. His monumental epic poem, Skabelsen, Mennesket og Messias, in particular, received severe criticism from Welhaven. This conflict was exacerbated by Wergeland's position as a patriot at the forefront of criticizing pro-Danish factions, leading to a long-standing antagonistic relationship and heated debates between the two. However, his early poetry has since been reassessed and is now more favorably recognized, even regarded as strangely modernistic while retaining elements of traditional Norwegian Eddic verse.

Influenced by classical Norse poets from the 6th to 11th centuries, Wergeland's writing was evocative and often intentionally veiled, featuring elaborate kennings that required extensive context to decipher. From an early stage, he experimented with free verse, eschewing traditional rhymes or meter. His metaphors were vivid and complex, and many of his poems were notably long, challenging the reader to deep contemplation, much like the works of his contemporaries Byron and Shelley, or even Shakespeare. This free form and potential for multiple interpretations were particularly offensive to Welhaven, who adhered to an aesthetic view of poetry that emphasized concentration on a single topic.

Wergeland's intellectual forefathers included those from the Enlightenment and French Revolution, evident in his critique of power abuse and his advocacy for democratic ideals. Although he initially wrote in Danish, he became a proponent for the development of a distinct and independent language for Norway, anticipating the linguistic efforts of Ivar Aasen by 15 years. His most prominent poetical symbols are the flower and the star, symbolizing heavenly and earthly love, nature, and beauty.

3. Political and Social Activism

Henrik Wergeland was not only a literary figure but also a fervent political and social activist, playing a pivotal role in shaping Norwegian national consciousness and championing progressive ideals.

3.1. National Movement and Constitution Day

Wergeland became a symbol of the fight for the celebration of May 17th, which eventually became Norway's national day. In 1829, he became a public hero following the infamous "battle of the Square" in Christiania. This event occurred because any celebration of the national day had been forbidden by royal decree. Wergeland was present during the tumult and became renowned for bravely standing up against the local governors. He later became the first person to deliver a public address on behalf of the day, earning him credit for having "initiated the day." To this day, his grave and statues are adorned with flowers by students and schoolchildren every year on May 17th. Notably, the Jewish community of Oslo pays their respects at his grave on this day, recognizing his successful efforts to repeal the constitutional ban on Jews entering Norway.

3.2. Social Reform and Advocacy for the Marginalized

Wergeland was deeply committed to social justice and the welfare of the common people. He tirelessly worked to alleviate the widespread poverty among the Norwegian peasantry, advocating for a simpler life and denouncing foreign luxuries, setting an example by wearing Norwegian homespun clothes.

He passionately argued for the emancipation of the oppressed and vulnerable, including his strong advocacy for allowing Jews into Norway. He also spoke out in favor of the rights of American slaves and supported Polish minorities within the Russian Empire, vehemently protesting against oppression in Spain. His efforts reflect his 18th-century Enlightenment perspective, emphasizing democracy and progress, and he actively appealed to the general populace, particularly laborers, to embrace these values. His suspicion of lawyers, especially their treatment of poor farmers, often led him into legal battles against them, which, while making him enemies, also underscored his defense of the marginalized.

3.3. Public Enlightenment and Engagement

Wergeland dedicated significant efforts to public education and enlightenment, aiming to foster a greater understanding of the constitutional rights granted to the Norwegian people. He actively traveled across Norway, visiting remote villages to preach and educate impoverished farmers. He was instrumental in establishing popular libraries throughout the country and engaged in newspaper editing, notably a radical magazine titled Statsborgeren from 1835 to 1837. He also authored textbooks and delivered numerous public addresses. His continuous advocacy for democratic values and the national cause led to his increasing popularity among the common people. In late 1838, King Carl Johan offered him a small "royal pension," which Wergeland accepted as remuneration for his work as a "public teacher," providing him sufficient income to marry and settle down. He later served as a librarian at the University Library from January 1836, and in 1840, he was selected as the first archivist of the National Archives of Norway, a position he held from January 4, 1841, until his retirement in autumn 1844. On April 17, 1841, he and Amalie moved to his new home, Grotten, situated near the new Norwegian royal palace, where he resided for the next few years.

4. Personal Life

Wergeland's personal life, particularly his marriage, provided him with both stability and new inspiration.

4.1. Marriage and Family

Wergeland met Amalie Sofie Bekkevold, then 19 years old and the daughter of an inn proprietor, at a small inn at the Christiania quay. He quickly fell in love and proposed the same autumn. They were married on 27 April 1839, in the church of Eidsvoll, with Wergeland's father officiating the ceremony.

Despite her working-class background, Amalie was charming, witty, and intelligent, quickly endearing herself to Wergeland's family. His sister, Camilla Collett, became her lifelong trusted friend. While their marriage did not produce any biological children, the couple adopted Olaf, an illegitimate son Wergeland had fathered in 1835. Wergeland ensured Olaf received an education, and Olaf Knudsen, as he was known, later became a prominent teacher and the founder of the Norwegian School-gardening movement.

Amalie became the muse for a new collection of Wergeland's love poems, distinguished by their imagery of flowers, contrasting with his earlier love poems that had been filled with images of stars. After Wergeland's death, Amalie married Nils Andreas Biørn, the priest who officiated Wergeland's funeral and an old college friend. She had eight children with Biørn. However, upon her death many years later, her eulogy famously noted: "The widow of Wergeland has died at last, and she has inspired poems like no-one else in Norwegian literature."

5. Controversies and Criticisms

Wergeland's life and career were marked by significant disputes, critical receptions, and personal challenges that shaped his public image and personal struggles.

5.1. Literary Disputes

From 1830 to 1835, Wergeland was subjected to severe attacks from critics, most notably Johan Sebastian Welhaven. Welhaven, a classicist, could not tolerate Wergeland's innovative and "explosive" writing style, publishing an essay specifically criticizing it. In response, Wergeland released several poetical farces under the pseudonym "Siful Sifadda." This conflict, which originated as a mock-quarrel in the Norwegian Students' Community, escalated into a prolonged newspaper dispute lasting nearly two years. Welhaven's criticisms and the accompanying slander from his associates created a lasting prejudice against Wergeland and his early works.

5.2. Personality and Public Image

Wergeland had a hot temper and fought willingly for social justice. At the time, poverty was common in the rural areas, and serfdom was widespread. He was generally suspicious of lawyers due to their attitude towards farmers, particularly impoverished ones, and often engaged in legal battles against them, as lawyers could legally seize small homesteads. Wergeland made significant enemies through these actions, and in one notable case, a judicial problem lasted for years and nearly led him to bankruptcy. This particular quarrel began at Gardermoen, which was then a drill field for a section of the Norwegian army. In his plays, his nemesis, the procurator Jens Obel Praëm, was often cast as the devil himself. Wergeland was notably tall for his era, standing about 71 in (180 cm), a head taller than most of his contemporaries. He was often observed gazing upwards, especially while riding his horse through town. His horse, Veslebrunen (little brown), a small Norwegian breed (though not a pony), meant that Wergeland's feet often dragged on the ground while riding.

5.3. Political Criticisms and Personal Hardships

Wergeland also faced considerable political backlash. After years of being rejected for chaplain or priest positions due to his perceived "irresponsible" and "unpredictable" lifestyle, compounded by his ongoing legal dispute with procurator Jens Obel Praëm, he accepted a small "royal pension" from King Carl Johan in late 1838. This acceptance, however, drew suspicion from his former comrades in the republican movement, who accused him of betraying their cause by taking money from the King. Wergeland's view of Carl Johan was complex; while he saw him as a symbol of the French Revolution's values, he also recognized him as the Swedish king who had hindered Norway's national independence.

The radicals labeled Wergeland a renegade, forcing him to defend himself extensively. He often felt isolated and betrayed. During one student party, his attempt to propose a toast was rudely interrupted, leading him to despair and break a bottle against his forehead. Only one physician later recalled Wergeland weeping that night. When the students later formed a procession, they left him behind, but a single student, Johan Sverdrup (who would later become the father of Norwegian parliamentarism), offered him his arm, lifting Wergeland's spirits. This marked a symbolic walk between two generations of the Norwegian left-wing movement.

Adding to his struggles, Wergeland was barred from publishing in some major newspapers, including Morgenbladet, which refused to print his responses or even his poetic defenses. In response to their claim that he was "irritable and in a bad mood," Wergeland famously penned a free-meter poem:

I in a bad mood, Morgenblad? I, who need nothing more than a glimpse of sun to burst out in loud laughter, from a joy I cannot explain?

This poem was eventually published in another newspaper, and Morgenbladet later issued an apology to Wergeland in the spring of 1846.

Wergeland also faced significant financial hardship. In January 1844, the court reached a compromise in the long-standing Praëm case, requiring Wergeland to pay a bail of 800 speciedaler, a sum far exceeding his means. He felt humiliated and was forced to sell his home, Grotten, which was purchased by a sympathetic friend the following winter. The immense psychological pressure from these disputes and financial burdens may have contributed to his declining health.

6. Illness and Death

Wergeland's final years were marked by a severe decline in health, yet he continued his prolific literary output until his very last days.

6.1. Period of Illness

In the spring of 1844, Wergeland contracted pneumonia, forcing him to stay at home for two weeks. While recovering, he insisted on participating in the national celebrations that year. His sister, Camilla, noted his appearance, describing him as "pale as death, but in the spirit of 17 May" on his way to the festivities. Soon after, his illness recurred, accompanied by symptoms of tuberculosis, which proved to be terminal. Theories about the exact nature of his illness also include the possibility of lung cancer, stemming from a lifetime of smoking, the dangers of which were largely unknown at the time.

Despite his worsening condition, Wergeland maintained an astonishing level of productivity from his sickbed during his last year. He wrote rapidly, producing numerous letters, poems, political statements, and plays. Due to his dire economic situation, he was forced to move from Grotten to a smaller house, Hjerterum, in April 1845. His new home, however, was not yet finished, necessitating a ten-day stay at the national hospital Rikshospitalet. During this period, he composed some of his most renowned "sickbed poems." He continued to write almost until the very end, with his last known poem dated 9 July, merely three days before his death.

6.2. Funeral and Burial

Henrik Wergeland passed away at his home in the early morning hours of 12 July 1845. His funeral, held on 17 July, was a monumental public event, attended by thousands of mourners, many of whom had traveled from the districts surrounding Christiania. The officiating priest, expecting only a few hundred attendees, was astonished by the turnout, which numbered ten times his initial estimate. Wergeland's coffin was carried by Norwegian students, who reportedly insisted on bearing it themselves, while the designated wagon proceeded in front of them, empty.

Throughout the afternoon, Wergeland's grave was left open, allowing countless individuals to pay their respects by spreading flowers on his coffin until evening. Three days later, on 20 July, his father, Nicolai Wergeland, expressed his profound gratitude in Morgenbladet, stating that his son had finally received the honor he deserved:

Now I see how you all loved him, how you revered him... God reward and bless you all! The brother you held in such esteem had a risky beginning, was misunderstood a long time and suffered long, but had a beautiful ending. His life was not strewn with roses, but his death and grave the more -

Initially, Wergeland was interred in a humble section of the churchyard. However, his friends soon began advocating in newspapers for a more prominent burial site. Consequently, his remains were relocated to his current grave in 1848. Following this, a debate arose regarding a suitable monument for his grave. The monument that now marks his resting place was generously provided by Swedish Jews and was officially unveiled on 17 June 1849, after a six-month delay.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

Henrik Wergeland's lasting impact on Norwegian society, culture, and literature is profound, solidifying his status as a national icon whose contributions continue to be celebrated and reevaluated.

7.1. Historical and Cultural Impact

Wergeland is recognized as a leading pioneer in the development of a distinctly Norwegian literary heritage and modern Norwegian culture. He was endowed with natural leadership qualities and tirelessly dedicated himself to inspiring patriotism and nation-building through his energetic lectures, sermons, newspaper editing, library initiatives, textbook authorship, and poetry.

His strong sense of social justice led him to champion the rights of the oppressed. He spoke passionately for the liberation of Jews in Norway, advocated for the abolition of slavery in the United States, supported the rights of Polish minorities under Russian rule, and protested against oppression in Spain. Operating from an 18th-century Enlightenment perspective, he fervently promoted democratic ideals and social progress, specifically appealing to the working class and general populace.

Wergeland became a powerful symbol for the Norwegian Left-wing movement, and his influence resonated through subsequent generations of Norwegian poets and thinkers, extending to the present day. Many later poets acknowledge their artistic debt to him. As the Norwegian poet Ingeborg Refling Hagen eloquently put it, "When in our footprints something sprouts,/ it's a new growth of Wergeland's thoughts." His prominent poetical symbols, the flower and the star, continue to represent heavenly and earthly love, nature, and beauty in Norwegian literature.

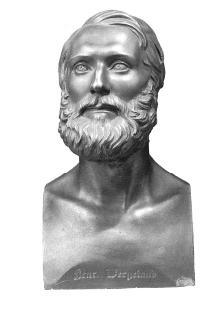

7.2. Memorials and Commemoration

Henrik Wergeland has been honored in various ways, cementing his place in Norwegian memory. His statue stands prominently between the Royal Palace and the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament) along Oslo's main street, with its back turned towards the Nationaltheatret. This monument was erected on 17 May 1881, and the dedicatory oration was delivered by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, another towering figure in Norwegian literature. Annually on May 17th, students from the University of Oslo place a wreath of flowers on his statue. During World War II, the Nazi occupation forces explicitly forbade any celebration of Wergeland, a testament to his enduring patriotic significance.

Ingeborg Refling Hagen, among others, initiated an annual celebration on Wergeland's birthday. She established the traditional "flower-parade" and keeps his memory alive through recitations, songs, and performances of his plays. Beyond Norway, a statue of Henrik Wergeland can also be found in Fargo, North Dakota, in the United States.

7.3. Reception and Reassessment

While Wergeland's early works faced significant criticism for their unconventional style, leading to disputes with figures like Johan Sebastian Welhaven, his poetry has undergone substantial reassessment in recent times. His early poetic efforts, once denounced as "wild and formless," are now recognized more favorably, even regarded as surprisingly modernistic while simultaneously retaining elements of traditional Norwegian Eddic verse. This ongoing reinterpretation acknowledges the depth and complexity of his artistic vision, confirming his lasting impact on the literary landscape.

8. Works

Henrik Wergeland's extensive literary output includes poetry, dramas, historical works, and essays:

- Irreparible Tempus (1828)

- Sinclairs død (1828)

- Digte, Første Ring (Poems, First Circle) (1829)

- Skabelsen, Mennesket og Messias (Creation, Man and the Messiah) (1830), remodeled as Mennesket (Man) in 1845

- Spaniolen (The Spaniard) (1833)

- Digte, Annen Ring (Poems, Second Circle) (1833)

- Barnemordersken (The Child Murderess) (1835)

- Søkadetterne (The Sea Cadets) (1837)

- Campbellerne (The Campbells) (1837)

- Digte (Poems) (1838)

- Czaris (1838)

- Stockholmsfareren (The Stockholm Traveler) (1838)

- Engelsk salt (English Salt) (1838)

- Den konstitutionelle (The Constitutional) (1838)

- Vinægers fjeldeventyr (Vinegar's Mountain Adventure) (1838)

- Jan van Huysums Blomsterstykke (Jan van Huysum's Flower-piece) (1840)

- Svalen (The Swallow) (1841)

- Norges Konstitusjons Historie (The History of the Norwegian Constitution) (1841-1843)

- Jødesagen I Det Norske Storthing (The Jewish Case in the Norwegian Parliament) (1842)

- Jøden (The Jew) (1842)

- Venetianerne (The Venetians) (1843)

- Jødinden (The Jewess) (1844)

- Den engelske lods (The English Pilot) (1844)

- Hasselnødder (Hazelnuts) (1845)

- Det befriede Europa (The Liberated Europe) (1845)

- Kongens ankomst (The King's Arrival) (1845)

The collected writings of Henrik Wergeland (Samlede Skrifter : trykt og utrykt) were published in 23 volumes between 1918 and 1940, edited by Herman Jæger and Didrik Arup Seip. An earlier compilation also titled Samlede Skrifter (9 vols., Christiania, 1852-1857) was edited by H. Lassen. Wergeland's lyrics have been translated into English by several scholars, including Illit Gröndal, G. M. Gathorne-Hardy, Jethro Bithell, Axel Gerhard Dehly, and Anne Born.