1. Overview

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 - November 27, 1978) was an American politician and a pivotal figure in the LGBTQ+ rights movement. He achieved national recognition as the first openly gay man elected to public office in California, securing a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977. Milk's political career, though brief, was marked by his fierce advocacy for individual freedoms, social justice, and neighborhood empowerment. He championed progressive policies, including a landmark anti-discrimination ordinance based on sexual orientation. His life was tragically cut short when he and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone were assassinated by former Supervisor Dan White on November 27, 1978.

Milk's assassination and the controversial trial that followed sparked widespread outrage, including the White Night riots, and brought significant attention to the injustices faced by the gay community. Despite a short tenure, Milk became an enduring icon and a martyr for LGBTQ+ rights, symbolizing the struggle for visibility, equality, and hope. His legacy continues to inspire activists and politicians, influencing the ongoing fight for human rights and contributing to the broader understanding of civil liberties in America. In 2009, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of his profound impact.

2. Early Life and Background

Harvey Milk's early life and varied career before his full immersion in politics reveal a gradual transformation from a conservative background to a passionate advocate for social change.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Harvey Bernard Milk was born on May 22, 1930, in Woodmere, New York, a suburb of New York City. He was the younger son of Litvak parents, William Milk and Minerva Karns. His grandfather, Morris Milk, owned a department store and played a role in organizing the first synagogue in the area. As a child, Milk was often teased for his prominent ears, large nose, and oversized feet, leading him to develop a persona as a class clown to gain attention. During his school years, he participated in football and developed a strong passion for opera. His high school yearbook entry read: "Glimpy Milk-and they say WOMEN are never at a loss for words."

Milk graduated from Bay Shore High School in Bay Shore, New York, in 1947. He then attended New York State College for Teachers in Albany (now the University at Albany, SUNY) from 1947 to 1951, where he majored in mathematics. He also contributed to the college newspaper. A classmate from that period recalled him as "a man's man," suggesting that his homosexuality was not openly perceived or discussed at the time.

3. Move to San Francisco and Political Awakening

Milk's relocation to San Francisco and his experiences in the burgeoning Castro District were pivotal in transforming him into a political activist and a leader in the gay rights movement.

3.1. Life in San Francisco and the Castro

Since the end of World War II, San Francisco, a major port city, had become home to a significant number of gay men who, having been discharged from the military, chose to remain rather than return to their hometowns where they might face ostracism. By 1969, the Kinsey Institute estimated that San Francisco had more gay people per capita than any other American city, making it the focus of a National Institute of Mental Health survey on homosexuals. Milk and Jack McKinley were among the thousands of gay men drawn to San Francisco. McKinley, a stage manager, was offered a job in the New York City production of Jesus Christ Superstar after arriving in San Francisco with the Broadway touring company of Hair. Their tumultuous relationship ended, but Milk found the city appealing and decided to stay, initially working at an investment firm. In 1970, increasingly frustrated by the political climate following the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, Milk was fired from his job after refusing to cut his long hair.

Milk then drifted from California to Texas to New York without a steady job or clear plan. In New York City, he reconnected with director Tom O'Horgan's theater company as a "general aide" and associate producer for productions like Lenny and Eve Merriam's Inner City. His time among the flower child cast members significantly eroded his conservatism. A 1971 The New York Times story described Milk as "a sad eyed man-another aging hippie with long, long hair, wearing faded jeans and pretty beads." His former lover, Craig Rodwell, wondered if it could be the same person. Despite concerns from a Wall Street friend about his lack of a plan, Milk was remembered as "happier than at any time I had ever seen him in his entire life." In Rosa von Praunheim's 1971 documentary short film Homosexuals in New York, Milk appeared as an exuberant protester on Christopher Street Day.

Milk later met Scott Smith, 18 years his junior, and they began a relationship. Milk and Smith returned to San Francisco, living on their savings. In March 1973, after a roll of film Milk left at a local shop was ruined, he and Smith used their last 1.00 K USD to open Castro Camera on Castro Street. This store quickly became a central hub for the burgeoning gay community in the Castro.

3.2. Early Political Campaigns

In the late 1960s, local gay rights organizations like the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) and the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) began actively combating police harassment and entrapment in San Francisco. Laws were strict; oral sex was a felony, and in 1970, nearly 90 people were arrested for public sex in city parks at night, with 2,800 gay men arrested for public sex in 1971 alone. Any morals charge arrest required registration as a sex offender.

Key California politicians, including Congressman Phillip Burton and Assemblyman Willie Brown, recognized the growing political influence of homosexuals in the city and sought their votes. Brown pushed for legalization of sex between consenting adults in 1969, though unsuccessfully. Moderate Supervisor Dianne Feinstein also courted SIR for her mayoral bid. Ex-policeman Richard Hongisto actively appealed to the gay community and won his sheriff's campaign in 1971, demonstrating the community's nascent political power.

SIR members, including Jim Foster, Rick Stokes, and Advocate publisher David B. Goodstein, formed the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club ("Alice") in 1971. This club worked to influence liberal politicians, successfully advocating for an ordinance outlawing employment discrimination based on sexual orientation in 1972 with Feinstein's support. Foster gained national prominence as the first openly gay man to address a political convention at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, making him a key voice for the gay community.

Milk's interest in politics was sparked by personal frustrations with civic problems. In 1973, a state bureaucrat demanded a 100 USD deposit against state sales tax from Milk's Castro Camera. Milk vehemently protested, eventually getting the deposit reduced to 30 USD. Around the same time, he was infuriated by government priorities when a teacher had to borrow a projector from his store because school equipment was broken. Witnessing John N. Mitchell's evasive "I don't recall" responses during the Watergate hearings further solidified his resolve. He later stated, "I finally reached the point where I knew I had to become involved or shut up," deciding to run for city supervisor.

Milk's initial foray into politics was met with resistance from the established gay political figures. Jim Foster, a veteran activist, refused to endorse Milk, stating, "There's an old saying in the Democratic Party. You don't get to dance unless you put up the chairs. I've never seen you put up the chairs." This marked the beginning of an antagonistic relationship between Milk and the Alice Club. However, some gay bar owners, frustrated by police harassment and Alice's perceived timidity, endorsed Milk.

Journalist Frances FitzGerald described Milk as a "born politician," despite his initial inexperience. His 1973 campaign lacked funding, support, or staff, relying instead on a message of sound financial management and prioritizing individuals over large corporations. He supported reorganizing supervisor elections from citywide to district ballots, aiming to empower neighborhoods. His platform also included culturally liberal views, such as opposing government interference in private sexual matters and favoring marijuana legalization. Milk's flamboyant speeches and media savvy gained him significant press, securing 16,900 votes and a 10th-place finish out of 32 candidates. Had district elections been in place, he would have won.

From early in his career, Milk excelled at coalition building. When the Teamsters union sought support for a strike against beer distributors, Milk offered assistance with gay bars in exchange for the union hiring more gay drivers. He successfully rallied gay bars in the Castro District to boycott the beer, with additional support from Arab and Chinese grocers. This alliance solidified his relationship with organized labor and led him to adopt the moniker "The Mayor of Castro Street." As the Castro's influence grew, so did Milk's reputation. Tom O'Horgan noted, "Harvey spent most of his life looking for a stage. On Castro Street he finally found it."

Tensions arose between older residents of the Most Holy Redeemer Parish and the influx of gay individuals into the Castro. In 1973, when gay men attempted to open an antique shop, the Eureka Valley Merchants Association (EVMA) tried to block their business license. In response, Milk and other gay business owners founded the Castro Village Association, with Milk as its president. He advocated for gay people to support gay businesses and organized the first Castro Street Fair in 1974 to boost local commerce. Over 5,000 people attended, and some EVMA members were astonished by the fair's commercial success, which surpassed any previous single day's business.

Although a newcomer, Milk emerged as a leader in the Castro. Taking his political aspirations more seriously, he ran for supervisor again in 1975, cutting his long hair, abstaining from marijuana, and vowing to avoid gay bathhouses. His campaigning earned him support from teamsters, firefighters, and construction unions. Castro Camera became the neighborhood's political hub, with Milk often recruiting passersby-many of whom he found attractive-to volunteer for his campaigns.

Milk championed small businesses and neighborhood growth, contrasting with Mayor Joseph Alioto's policy since 1968 of attracting large corporations, which critics termed the "Manhattanization of San Francisco." In 1975, George Moscone, who had instrumental in repealing California's sodomy law, was elected mayor. Moscone recognized Milk's influence by visiting his election night headquarters, personally thanking him, and offering him a position as a city commissioner. Milk placed seventh in the election, just one position shy of a supervisor seat.

Despite new city leadership, conservative strongholds remained. Moscone appointed Charles Gain as police chief, against the wishes of the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD). Gain, who had criticized the police for racial insensitivity and alcohol abuse, became a national news story for welcoming openly gay officers, further alienating much of the force.

Milk's role as a representative for San Francisco's gay community expanded when, on September 22, 1975, Oliver Sipple, a former Marine, saved President Gerald Ford from an assassination attempt in San Francisco. Sipple, who had been Joe Campbell's lover before Campbell's suicide attempt, wished his sexuality to remain private. However, Milk seized the opportunity to demonstrate gay heroism, telling a friend, "It's too good an opportunity. For once we can show that gays do heroic things, not just all that ca-ca about molesting children and hanging out in bathrooms." Milk contacted a newspaper, leading to columnist Herb Caen outing Sipple in the San Francisco Chronicle, which was then picked up by national media. Time named Milk a leader in San Francisco's gay community. Sipple, despite being involved in the gay community for years, sued the Chronicle for invasion of privacy. President Ford sent Sipple a thank-you note, but Milk claimed Sipple's sexuality was why he didn't receive a White House invitation.

In 1976, Mayor Moscone appointed Milk to the Board of Permit Appeals, making him the first openly gay city commissioner in the United States. Milk then decided to run for the California State Assembly. The district was favorable to him, encompassing many neighborhoods where Milk had strong support. In the previous supervisor race, Milk had received more votes than the incumbent assemblyman. However, Moscone had already agreed with the assembly speaker to back another candidate, Art Agnos. Furthermore, Moscone's order stipulated that appointed or elected officials could not campaign while performing their duties.

Milk served only five weeks on the Board of Permit Appeals before Moscone was forced to fire him when Milk announced his State Assembly candidacy; Rick Stokes replaced him. This firing, along with the "backroom deal" for Agnos, fueled Milk's campaign as he embraced the identity of a political underdog. He criticized the city and state governments and accused the prevailing gay political establishment, especially the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, of excluding him, calling Jim Foster and Stokes "gay Uncle Toms." He enthusiastically adopted a local weekly magazine's headline: "Harvey Milk vs. The Machine." The Alice B. Toklas Club did not endorse either Milk or Agnos in the primary, while other gay-aligned groups endorsed Agnos or gave dual endorsements.

Milk's campaign, run from Castro Camera, was notoriously disorganized. Volunteers were plentiful, but notes and lists were kept on scrap papers, and campaign funds came directly from the cash register without proper accounting. An 11-year-old neighborhood girl served as the campaign manager's assistant. Milk himself was highly energetic and prone to temperamental outbursts, quickly recovering to shout excitedly about other matters. Many of his rants were directed at Scott Smith, who became increasingly disillusioned with the man who was no longer the laid-back hippie he had fallen in love with.

Despite his manic energy, Milk was dedicated, good-humored, and had a genius for attracting media attention. He spent long hours registering voters and shaking hands at bus stops and movie theater lines, seizing every opportunity to promote himself. His success was evident. With numerous volunteers, he had dozens standing along the busy thoroughfare of Market Street as "human billboards," holding "Milk for Assembly" signs. He also distributed campaign literature to various groups, including the influential Peoples Temple, accepting their volunteers to work his phones. In 1978, Milk wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter defending the cult leader Jim Jones as "a man of the highest character." This relationship with the Temple mirrored that of other Northern California politicians, as Jones and his followers were a "potent political force" that helped elect Mayor Moscone, District Attorney Joseph Freitas, and Sheriff Richard Hongisto. When Milk discovered Jones was backing both him and Art Agnos, he told a friend, "Well fuck him. I'll take his workers, but, that's the game Jim Jones plays." To his volunteers, however, he instructed: "Make sure you're always nice to the Peoples Temple. If they ask you to do something, do it, and then send them a note thanking them for asking you to do it."

The race was close, and Milk lost by fewer than 4,000 votes. Agnos offered Milk valuable advice, criticizing his speeches as "a downer... You talk about how you're gonna throw the bums out, but how are you gonna fix things-other than beat me? You shouldn't leave your audience on a down." Following his loss, Milk, realizing the Toklas Club would never fully support him, co-founded the San Francisco Gay Democratic Club.

4. Political Career

Harvey Milk's tenure as an elected official, though brief, was marked by significant legislative achievements and a political philosophy centered on empowering marginalized communities and addressing everyday issues.

4.1. Election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors

The defeat of the Dade County civil rights ordinance in Miami in 1977, championed by singer Anita Bryant's "Save Our Children" campaign, shocked gay activists nationwide. The campaign effectively garnered 64,000 signatures to put the issue to a county-wide vote. They ran television advertisements contrasting the Orange Bowl Parade with San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Parade, claiming Dade County would become a "hotbed of homosexuality" where "men... cavort with little boys." The ordinance was overwhelmingly repealed, with 70% voting against it in the largest special election turnout in Dade County's history. This victory energized conservative Christian fundamentalists, who saw an opportunity for a new political cause.

Gay activists were dismayed by the lack of support. On the night of the Dade County vote, an impromptu demonstration of over 3,000 Castro residents marched through the streets, chanting "Out of the bars and into the streets!" Milk led the 5 mile course, deliberately keeping it moving to prevent a riot. He famously declared, "This is the power of the gay community. Anita's going to create a national gay force." This scenario repeated itself as similar civil rights ordinances were overturned in Saint Paul, Minnesota; Wichita, Kansas; and Eugene, Oregon throughout 1977 and 1978.

California State Senator John Briggs, aspiring to be governor in 1978, seized on this momentum. Impressed by the voter turnout in Miami, he drafted a bill to ban gay and lesbian teachers, and any public school employees supporting gay rights, from schools throughout California. Briggs privately dismissed his anti-gay stance as "Just politics." Random attacks on gays increased in the Castro, and when police response was deemed inadequate, gay groups patrolled the neighborhood themselves. On June 21, 1977, gay man Robert Hillsborough died from 15 stab wounds, with his attackers chanting "Faggot!" Mayor Moscone and Hillsborough's mother blamed Anita Bryant and John Briggs, who, a week prior, had called San Francisco a "sexual garbage heap" due to its homosexual population. Weeks later, the 1977 San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade drew 250,000 to 375,000 attendees, the largest Gay Pride event to date, with newspapers attributing the increased numbers to John Briggs's actions.

In November 1976, San Francisco voters approved a reorganization of supervisor elections, shifting from citywide ballots to district-based representation. This change favored Milk, who quickly became the leading candidate in District 5, which included Castro Street.

The opposition to gay rights fueled a surge in gay political engagement in San Francisco. Seventeen candidates, more than half of them gay, entered the supervisor race for the Castro District. The New York Times noted a "veritable invasion of gay people into San Francisco," estimating the city's gay population at 100,000 to 200,000 out of 750,000. The Castro Village Association had grown to 90 businesses, and the local bank branch, once the city's smallest, became its largest, requiring expansion. Milk's biographer Randy Shilts noted that Milk's campaign was driven by "broader historical forces."

Milk's main opponent was Rick Stokes, a lawyer backed by the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club. Stokes had been openly gay longer than Milk, having even endured electroshock therapy in an attempt to "cure" his homosexuality. However, Milk was more vocal about the role of gay people in politics. Stokes claimed he was "just a businessman who happens to be gay," suggesting a more assimilated approach. Milk's contrasting populist philosophy, as conveyed to The New York Times, was: "We don't want sympathetic liberals, we want gays to represent gays... I represent the gay street people-the 14-year-old runaway from San Antonio. We have to make up for hundreds of years of persecution. We have to give hope to that poor runaway kid from San Antonio. They go to the bars because churches are hostile. They need hope! They need a piece of the pie!"

Milk's platform also included advocating for larger, less expensive childcare facilities, free public transportation, and a civilian board to oversee the police. He consistently promoted neighborhood issues. He used the same energetic campaign tactics as in previous races: human billboards, hours of handshaking, and dozens of speeches urging gay people to have hope. This time, The San Francisco Chronicle endorsed him. On election day, November 8, 1977, he won by 30% against sixteen other candidates. After his victory, he rode triumphantly into Castro Street on the back of his campaign manager's motorcycle, escorted by Sheriff Richard Hongisto, to what a newspaper described as a "tumultuous and moving welcome."

Around this time, Milk began a relationship with Jack Lira, a young man who was frequently drunk in public and often had to be escorted out of political events by Milk's aides. Milk had been receiving increasingly violent death threats since his run for the California State Assembly. Concerned about becoming an assassination target due to his raised public profile, he recorded his thoughts on tape, including whom he wished to succeed him if he were killed. He famously added: "If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door."

4.2. Tenure as Supervisor

Milk's swearing-in on January 8, 1978, made national headlines, as he became the first non-incumbent openly gay man elected to public office in the United States. He likened himself to pioneering African American baseball player Jackie Robinson and walked to City Hall arm in arm with Jack Lira, declaring, "You can stand around and throw bricks at Silly Hall or you can take it over. Well, here we are." His swearing-in was part of a wave of new political representation in San Francisco: also sworn in were a single mother (Carol Ruth Silver), a Chinese American (Gordon Lau), and an African American woman (Ella Hill Hutch)-all firsts for the city. Dan White, a former police officer and firefighter, was also a first-time supervisor, expressing pride that his grandmother witnessed his swearing-in.

Milk's energy, penchant for pranks, and unpredictable nature often exasperated Board of Supervisors President Dianne Feinstein. In his first meeting with Mayor Moscone, Milk boldly declared himself the "number one queen" and asserted that Moscone would have to work through him, not the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, to secure the city's gay votes-which constituted a quarter of San Francisco's electorate. Milk quickly became Moscone's closest ally on the Board of Supervisors.

Milk frequently targeted large corporations and real estate developers. He expressed outrage when a parking garage was planned to replace homes downtown and attempted to pass a commuter tax to make office workers living outside the city pay for city services they used. Milk often voted against Feinstein and other more experienced board members. Early in his term, Milk initially agreed with fellow Supervisor Dan White, whose district was two miles south of the Castro, that a mental health facility for troubled adolescents should not be located there. However, after learning more about the facility, Milk changed his vote, ensuring White's defeat on an issue White had passionately championed during his campaign. White never forgot this, and subsequently opposed every initiative and issue Milk supported.

Milk began his tenure by sponsoring a civil rights bill that outlawed discrimination based on sexual orientation in public accommodations, housing, and employment. This ordinance was hailed by The New York Times as the "most stringent and encompassing in the nation" and a clear demonstration of "the growing political power of homosexuals." Only Supervisor White voted against it. Mayor Moscone enthusiastically signed it into law using a light blue pen Milk had given him for the occasion.

Another bill Milk focused on was designed to address the city's top complaint according to a recent citywide poll: dog excrement. Within a month of his swearing-in, he began working on a city ordinance requiring dog owners to scoop their pets' feces. This "pooper scooper law" received extensive coverage from San Francisco television and newspapers. Anne Kronenberg, Milk's campaign manager, noted he was "a master at figuring out what would get him covered in the newspaper." He famously invited the press to Duboce Park to explain the law's necessity, and while cameras were rolling, he seemingly accidentally stepped in dog feces. His staffers knew he had scouted the perfect spot for this public display for an hour before the press conference. This stunt earned him the most fan mail of his political tenure and was picked up by national news.

Milk eventually grew tired of Lira's drinking and considered ending their relationship. A few weeks later, Lira called, demanding Milk come home. Milk arrived to find Lira had hanged himself. Already prone to severe depression, Lira had previously attempted suicide. One of his suicide notes indicated his distress over the anti-gay campaigns of Anita Bryant and John Briggs.

4.3. Key Political Issues and Activities

John Briggs was forced to drop out of the 1978 race for California governor, but he garnered enthusiastic support for Proposition 6, also known as the Briggs Initiative. This proposed law would have mandated the firing of gay teachers and any public school employees who supported gay rights. Briggs's messages supporting Proposition 6 were widespread across California. Harvey Milk actively campaigned against the bill throughout the state, vowing that even if Briggs won California, he would not win San Francisco. In their numerous public debates, which became sharp and quick-witted, Briggs argued that homosexual teachers sought to abuse and recruit children. Milk countered with law enforcement statistics showing that pedophiles primarily identified as heterosexual, and often dismissed Briggs's claims with humorous one-liners, such as: "If it were true that children mimicked their teachers, you'd sure have a helluva lot more nuns running around."

Attendance at Gay Pride marches during the summer of 1978 in Los Angeles and San Francisco surged. An estimated 250,000 to 375,000 people attended San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Parade, with newspapers crediting John Briggs for the higher numbers. Organizers encouraged participants to carry signs indicating their hometowns for the cameras, to highlight how far people traveled to live in the Castro District. Milk rode in an open car, holding a sign that read "I'm from Woodmere, N.Y." During this period, he delivered a version of what would become his most famous oration, the "Hope Speech," which The San Francisco Examiner reported "ignited the crowd":

On this anniversary of Stonewall, I ask my gay sisters and brothers to make the commitment to fight. For themselves, for their freedom, for their country... We will not win our rights by staying quietly in our closets... We are coming out to fight the lies, the myths, the distortions. We are coming out to tell the truths about gays, for I am tired of the conspiracy of silence, so I'm going to talk about it. And I want you to talk about it. You must come out. Come out to your parents, your relatives.

Despite the losses in gay rights battles across the country that year, Milk remained optimistic. He stated, "Even if gays lose in these initiatives, people are still being educated. Because of Anita Bryant and Dade County, the entire country was educated about homosexuality to a greater extent than ever before. The first step is always hostility, and after that you can sit down and talk about it." Citing potential infringements on individual rights, former California Governor Ronald Reagan, Governor Jerry Brown, and President Jimmy Carter all voiced their opposition to the proposition. On November 7, 1978, Proposition 6 was defeated by more than a million votes statewide, astonishing gay activists. In San Francisco, 75 percent of voters opposed it.

5. Assassination and Aftermath

The tragic assassinations of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone, followed by the controversial trial of Dan White and the public unrest it ignited, deeply affected San Francisco and influenced the course of legal reform.

5.1. Assassination

On November 10, 1978, just 10 months after being sworn in, Dan White resigned from his position on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, citing that his annual salary of 9.60 K USD was insufficient to support his family. Within days, White requested to withdraw his resignation and be reinstated, a request Mayor Moscone initially agreed to. However, after further consideration and intervention by other supervisors, Moscone was convinced to appoint someone more aligned with the growing ethnic diversity of White's district and the liberal leanings of the Board. This included considering a more progressive replacement, such as Federal Housing Officer Don Horanzy, instead of White.

Adding to the city's turmoil, on November 18 and 19, news broke of the Jonestown mass suicide, where 900 members of the Peoples Temple had died in Guyana. California Representative Leo Ryan was among those killed. White reportedly remarked to aides working for his reinstatement, "You see that? One day I'm on the front page and the next I'm swept right off."

Moscone planned to formally announce White's replacement on November 27, 1978. A half hour before the press conference, White bypassed metal detectors by entering City Hall through a basement window. He proceeded to Moscone's office, where witnesses heard shouting followed by gunshots. White shot Moscone in the shoulder and chest, then twice more in the head at close range. White then quickly walked to his former office, reloading his police-issue revolver with hollow-point bullets along the way. He intercepted Milk, asking him to step inside. Dianne Feinstein heard gunshots and called the police, then found Milk face down on the floor, shot five times, including twice in the head. Soon after, Feinstein announced to the press: "Today, San Francisco has experienced a double tragedy of immense proportions. As President of the Board of Supervisors, it is my duty to inform you that both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed, and the suspect is Supervisor Dan White." Milk was 48 years old; Moscone was 49.

Within an hour of the shootings, White called his wife from a nearby diner. She met him at a church, and together they went to the police where White turned himself in. In the immediate aftermath, thousands of people laid flowers on the steps of City Hall. That evening, 25,000 to 40,000 people formed a spontaneous candlelight march from Castro Street to City Hall. The following day, the bodies of Moscone and Milk were brought to the City Hall rotunda for mourners to pay their respects. Six thousand mourners attended a service for Mayor Moscone at St. Mary's Cathedral. Two memorials were held for Milk: a smaller service at Temple Emanu-El and a larger, more boisterous one at the Opera House.

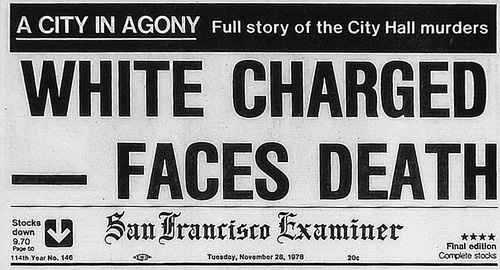

5.2. Dan White's Trial and the White Night Riots

The assassinations and Dan White's trial shocked the nation and exposed deep tensions between San Francisco's liberal populace and its predominantly working-class Irish police force, who largely resented the growing gay immigration and the city's progressive government. After White surrendered and confessed, he was held in his cell while former police colleagues told Harvey Milk jokes. Police officers openly wore "Free Dan White" T-shirts in the days following the murders. A San Francisco undersheriff later commented: "The more I observed what went on at the jail, the more I began to stop seeing what Dan White did as the act of an individual and began to see it as a political act in a political movement." White showed no remorse for his actions, only exhibiting vulnerability during an eight-minute phone call to his mother from jail.

The jury for White's trial consisted primarily of white, middle-class, Catholic San Franciscans, with gays and ethnic minorities largely excluded from the jury pool. Some jurors reportedly cried when they heard White's tearful recorded confession, which concluded with the interrogator (a childhood friend of White's and his police softball coach) thanking White for his honesty. White's defense attorney, Doug Schmidt, employed the legal defense of diminished capacity, arguing that his client was not responsible for his actions because "Good people, fine people, with fine backgrounds, simply don't kill people in cold blood." Schmidt claimed White's anguish and mental deterioration were exacerbated by a junk food binge the night before the murders, contrasting with his usual health-food conscious habits. This controversial argument was quickly dubbed the "Twinkie defense" by local newspapers.

On May 21, 1979, White was acquitted of the first-degree murder charge, but found guilty of voluntary manslaughter for both victims. He was sentenced to seven and two-thirds years in prison. With time served and good behavior, he would be released in five years. White reportedly cried upon hearing the verdict.

Acting Mayor Feinstein, Supervisor Carol Ruth Silver, and Milk's successor Harry Britt condemned the jury's decision. When the verdict was announced over the police radio, someone on the police band sang "Danny Boy". A surge of people from the Castro District marched back to City Hall, chanting "Avenge Harvey Milk" and "He got away with murder." The situation quickly escalated into pandemonium as rocks were thrown at the building's front doors. Milk's friends and aides attempted to de-escalate the situation, but the mob of over 3,000 ignored them, setting police cars on fire and cheering as they pushed a burning newspaper dispenser through the broken doors of City Hall. One rioter, when asked why they were destroying parts of the city, famously replied: "Just tell people that we ate too many Twinkies. That's why this is happening." The chief of police ordered his officers not to retaliate but to hold their ground. The White Night riots, as they became known, lasted several hours.

Later that evening, several police cruisers filled with officers in riot gear arrived at the Elephant Walk Bar on Castro Street. Milk's protégé Cleve Jones and San Francisco Chronicle reporter Warren Hinckle witnessed officers storming the bar and randomly beating patrons. After a 15-minute melee, they left the bar and attacked people walking along the street.

After the verdict, District Attorney Joseph Freitas faced a furious gay community demanding an explanation. Freitas admitted to feeling sympathetic towards White before the trial and neglected to question the biases of the interrogator who recorded White's confession (who was White's childhood friend and police softball coach), stating he did not want to embarrass the detective in front of his family in court. Freitas also failed to question White's mental state or lack of a history of mental illness, and did not present city politics as a potential motive for revenge. Supervisor Carol Ruth Silver testified on the final day of the trial that Milk and White were not friendly, but this was the only testimony the jury heard about their strained relationship. Freitas ultimately blamed the jury, claiming they had been "taken in by the whole emotional aspect of [the] trial."

The murders of Milk and Moscone and White's trial profoundly impacted city politics and the California legal system. In 1980, San Francisco ended district supervisor elections, fearing that a divisive Board of Supervisors would harm the city and that the system had contributed to the assassinations. However, a grassroots neighborhood effort successfully restored district elections in the mid-1990s, with the city returning to neighborhood representation in 2000. As a direct result of Dan White's trial, California voters amended the law to reduce the likelihood of acquittals for accused individuals who understood their actions but claimed diminished capacity. Diminished capacity was abolished as a defense, though courts still allowed evidence of it when determining incarceration, commitment, or other punishments for convicted defendants. The "Twinkie defense" has entered American popular culture, often oversimplified as a case where a murderer escaped justice due to eating junk food, obscuring White's lack of political acumen, his complex relationships with Moscone and Milk, and what San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen described as his "dislike of homosexuals."

Dan White served just over five years for the double homicide; he was released from prison on January 7, 1984. On October 21, 1985, White was found dead in his wife's garage, having committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. He was 39 years old. His defense attorney told reporters that White had been despondent over the loss of his family and the situation he had caused, adding, "This was a sick man."

When Milk's friends searched his closet for a suit for his casket, they discovered how much the decrease in his income as a supervisor had affected him, as all his clothes were falling apart and his socks had holes. His remains were cremated, and his ashes were divided. His closest friends scattered most of the ashes in San Francisco Bay. Other ashes were encapsulated and buried beneath the sidewalk in front of 575 Castro Street, the former location of Castro Camera. A memorial to Milk is located on the ground floor of the Neptune Society Columbarium in San Francisco. Harry Britt, one of four individuals Milk had designated as an acceptable replacement in case of his assassination, was chosen by acting Mayor Dianne Feinstein to fill Milk's vacant supervisor seat.

6. Legacy and Influence

Harvey Milk's enduring legacy is rooted in his pioneering political career, his impactful advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights and social justice, and his symbolic role as an icon for hope and visibility, despite his short life and tragic assassination.

6.1. Cultural and Political Impact

Milk's political career was fundamentally about making government responsive to individuals, promoting gay liberation, and emphasizing the importance of neighborhoods. Each campaign he undertook incorporated a new dimension into his public political philosophy. His 1973 campaign initially focused on the overlooked interests of small business owners in a city dominated by large corporations. While he never hid his homosexuality, it became a central issue during his 1976 California State Assembly race and was brought to the forefront in the 1977 supervisor election against Rick Stokes, as an extension of his ideas of individual freedom.

Milk firmly believed that neighborhoods fostered unity and a sense of small-town community, advocating that the Castro District should provide services for all its residents. He opposed the closure of an elementary school, seeing his neighborhood as having the potential to welcome everyone, even though most gay people in the Castro did not have children. He instructed his aides to prioritize fixing potholes and proudly announced that 50 new stop signs had been installed in District 5. His decision to prioritize the "pooper scooper law," addressing city residents' most frequent complaint about dog feces, underscored his pragmatic approach. Randy Shilts commented, "some would claim Harvey was a socialist or various other sorts of ideologues, but, in reality, Harvey's political philosophy was never more complicated than the issue of dogshit; government should solve people's basic problems."

Karen Foss, a communications professor, attributes Milk's impact on San Francisco politics to his unique persona. She describes him as a "highly energetic, charismatic figure with a love of theatrics and nothing to lose." Through humor, role reversal, and his status as both an insider and outsider, Milk fostered an environment conducive to dialogue on critical issues. He effectively integrated the diverse voices of his various constituencies. Milk had been a captivating speaker since his first campaign in 1973, and his oratorical skills only improved as a City Supervisor. His most renowned talking points became known as the "Hope Speech," a staple throughout his political career. It began with a playful acknowledgment of the accusation that gay people "recruit" impressionable youth: "My name is Harvey Milk-and I want to recruit you." A version delivered near the end of his life is considered his most powerful, with a particularly effective closing:

And the young gay people in the Altoona, Pennsylvanias and the Richmond, Minnesotas who are coming out and hear Anita Bryant in television and her story. The only thing they have to look forward to is hope. And you have to give them hope. Hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow, hope for a better place to come to if the pressures at home are too great. Hope that all will be all right. Without hope, not only gays, but the blacks, the seniors, the handicapped, the us'es, the us'es will give up. And if you help elect to the central committee and other offices, more gay people, that gives a green light to all who feel disenfranchised, a green light to move forward. It means hope to a nation that has given up, because if a gay person makes it, the doors are open to everyone.

In his final year, Milk stressed the importance of gay people being more visible to combat discrimination and violence. Although Milk never came out to his mother before her death, in his taped premonition of his assassination, he urged others to do so:

I cannot prevent anyone from getting angry, or mad, or frustrated. I can only hope that they'll turn that anger and frustration and madness into something positive, so that two, three, four, five hundred will step forward, so the gay doctors will come out, the gay lawyers, the gay judges, gay bankers, gay architects... I hope that every professional gay will say 'enough', come forward and tell everybody, wear a sign, let the world know. Maybe that will help.

Milk's assassination has become inextricably linked with his political effectiveness, partly because he was killed at the peak of his popularity. Historian Neil Miller writes, "No contemporary American gay leader has yet to achieve in life the stature Milk found in death." His legacy remains complex; Randy Shilts concludes his biography by stating that Milk's success, murder, and the injustice of White's verdict collectively represent the experience of all gays, making Milk's life "a metaphor for the homosexual experience in America." However, Frances FitzGerald observed that Milk's legend was difficult to sustain because no one could truly fill his void: "The Castro saw him as a martyr but understood his martyrdom as an end rather than a beginning. He had died, and with him a great deal of the Castro's optimism, idealism, and ambition seemed to die as well. The Castro could find no one to take his place in its affections, and possibly wanted no one." On the 20th anniversary of Milk's death, historian John D'Emilio remarked, "The legacy that I think he would want to be remembered for is the imperative to live one's life at all times with integrity." For such a brief political career, Cleve Jones attributes greater impact to his assassination than to his life: "His murder and the response to it made permanent and unquestionable the full participation of gay and lesbian people in the political process."

6.2. Tributes and Media

The City of San Francisco has honored Milk by naming several locations after him. The Harvey Milk Recreational Arts Center serves as headquarters for youth drama and performing arts programs. In 1996, Douglass Elementary in the Castro District was renamed the Harvey Milk Civil Rights Academy. The Eureka Valley Branch of the San Francisco Public Library was also renamed in his honor in 1981, located at 1 José Sarria Court, named for the first openly gay man to run for public office in the United States. On May 22, 2008, what would have been Milk's 78th birthday, a bust of his likeness was unveiled in San Francisco City Hall at the top of the grand staircase. Designed by Eugene Daub of the Firmin, Hendrickson Sculpture Group, the bust was accepted into the city's Civic Art Collection on June 2, 2008. Engraved on its pedestal is a quotation from one of Milk's audiotapes recorded in anticipation of his assassination: "I ask for the movement to continue because my election gave young people out there hope. You gotta give 'em hope." On the 82nd anniversary of his birth, a street in San Diego was renamed Harvey Milk Street, and a new park, Harvey Milk Promenade Park, was opened in Long Beach, California. At the intersection of Market and Castro streets in San Francisco, an enormous Gay Pride flag flies, situated in Harvey Milk Plaza. The San Francisco Gay Democratic Club changed its name to the Harvey Milk Memorial Gay Democratic Club in 1978 (now the Harvey Milk LGBTQ Democratic Club), and it is recognized as the largest Democratic organization in San Francisco.

In April 2018, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and Mayor Mark Farrell approved and signed legislation renaming Terminal 1 at San Francisco International Airport after Milk, with plans to install memorial artwork. This followed an earlier, unsuccessful attempt to rename the entire airport in his honor. Officially opening on July 23, 2019, Harvey Milk Terminal 1 became the world's first airport terminal named after an LGBTQ+ community leader. In New York City, Harvey Milk High School operates as a program for at-risk youth, focusing on the specific needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students within the Hetrick-Martin Institute.

In July 2016, US Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus announced his intention to name the second ship of the Military Sealift Command's John Lewis-class oilers the USNS Harvey Milk. All ships of this class are named after civil rights leaders. The ship was officially named at a ceremony in San Francisco on August 16, 2016. Milk had served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War, aboard the submarine rescue ship Kittiwake, holding the rank of lieutenant, junior grade before being forced to accept an "other than honorable" discharge due to his homosexuality. The naming generated some controversy given Milk's anti-war stance later in his life, but it marked the first U.S. Navy ship named for an openly gay leader. Construction of the vessel began on December 13, 2019, with its launch occurring in November 2021.

In June 2018, responding to a grassroots effort, the city council of Portland, Oregon, voted to rename a thirteen-block southwestern section of Stark Street to Harvey Milk Street. Mayor Ted Wheeler stated that this act "sends a signal that we are an open and a welcoming and an inclusive community." In 2019, Paris named a square Place Harvey-Milk in Le Marais.

In 1982, freelance reporter Randy Shilts completed The Mayor of Castro Street, the first biography of Milk, written while Shilts faced difficulty securing stable employment as an openly gay journalist. The Times of Harvey Milk, a documentary film based on Shilts's material, won the 1984 Academy Award for Documentary Feature. Director Rob Epstein noted that while Milk's assassination felt life-changing in San Francisco, it was largely a brief, localized news story elsewhere. Milk's life was also explored in Helene Meyers's work, "Got Jewish Milk: Screening Epstein and Van Sant for Intersectional Film History," which examined his contemporary depiction and "Jewishness."

Milk's life has inspired various artistic works, including a musical theater production, an eponymous opera, and a cantata. He is also the subject of a children's picture book and a French-language historical novel for young-adult readers. The biopic Milk, released in 2008 after 15 years in development, was directed by Gus Van Sant and starred Sean Penn as Milk and Josh Brolin as Dan White. The film won two Academy Awards for Best Original Screenplay and Best Actor. Filming took eight weeks and often utilized extras who had been present at the actual historical events, including a scene depicting Milk's "Hope Speech" at the 1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade.

Milk was included in Time's "Time 100 Heroes and Icons of the 20th Century," recognized as "a symbol of what gays can accomplish and the dangers they face in doing so." According to writer John Cloud, Milk, despite his antics and publicity stunts, "none understood how his public role could affect private lives better than Milk... [he] knew that the root cause of the gay predicament was invisibility." The Advocate listed Milk third in its "40 Heroes" of the 20th century issue, quoting Dianne Feinstein: "His homosexuality gave him an insight into the scars which all oppressed people wear. He believed that no sacrifice was too great a price to pay for the cause of human rights."

In August 2009, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Milk the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his contributions to the gay rights movement, stating, "he fought discrimination with visionary courage and conviction." Milk's nephew, Stuart Milk, accepted the award on his uncle's behalf. Shortly thereafter, Stuart co-founded the Harvey Milk Foundation with Anne Kronenberg, with the support of Desmond Tutu, who also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 and served on the Foundation's advisory board. Later that year, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger designated May 22 as Harvey Milk Day and inducted Milk into the California Hall of Fame.

Since 2003, the GLBT Historical Society, a San Francisco-based museum, archives, and research center, has featured the story of Harvey Milk in three exhibitions. The estate of Scott Smith donated Milk's personal belongings, preserved after his death, to this institution. On May 22, 2014, the United States Postal Service issued a postage stamp honoring Harvey Milk, making him the first openly LGBTQ+ political official to receive this honor. The stamp features a photo taken in front of Milk's Castro Camera store and was unveiled on what would have been his 84th birthday.

Harry Britt, Milk's successor, summarized Milk's impact on the evening of his assassination in 1978: "No matter what the world has taught us about ourselves, we can be beautiful and we can get our thing together... Harvey was a prophet... he lived by a vision... Something very special is going to happen in this city and it will have Harvey Milk's name on it." In 2010, radio producer JD Doyle aired the two-hour "Harvey Milk Music" program on Queer Music Heritage, collecting music about and inspired by Milk's story.

In 2012, Milk was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago celebrating LGBTQ+ history and figures. He was also named one of the inaugural fifty American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn.

Musical and band references to Milk include:

- Blue Gene Tyranny's 1978 composition "Harvey Milk (Portrait)" which skillfully uses recordings of Milk's 1978 speeches.

- The punk band Dead Kennedys released a scathing version of "I Fought the Law" in 1987, rewritten from Dan White's perspective, changing the chorus to "I fought the law and I won" and including lyrics about "blowing George and Harvey's brains out" and "Twinkies are my best friends."

- A metal band named Harvey Milk was formed in Athens, Georgia, in the early 1990s and remains active.

- The band Concrete Blonde mentioned him in their 1989 single "God is a Bullet," stating, "John Lennon, King, Harvey Milk - all damned useless men."

- The opera "Harvey Milk," with music by Stewart Wallace and a libretto by Michael Korie, premiered in 1995 with the San Francisco Opera and was recorded in 1996.

- The 1999 film Execution of Justice, based on Emily Mann's book, recreates Milk's assassination.

- The 2000 TV movie American Justice: It's Not My Fault - The Strange Defense examined the assassination using archival footage of Milk and White.

- In 2004, playwright and actor Jade Esteban Estrada portrayed Milk in his one-man musical comedy Icons: The Lesbian and Gay History of the World Volume Two.

- In 1998, folk musician Zoë Lewis honored Milk in her song "Harvey" from the album Sheep.

- Brian Singer was slated to direct a biopic titled The Mayor of Castro Street, but its production was delayed due to the 2007-2008 WGA strike and remains unproduced.