1. Overview

Gontrand, also known as Gontran, Gontram, Guntram, Gunthram, Gunthchramn, and Guntramnus, was a prominent Merovingian monarch who reigned as King of Orléans from 561 AD until his death on March 28, 592 AD. Born around 532 in Soissons, he was the third-eldest and second-eldest surviving son of Chlothar I and Ingunda. Upon his father's demise in 561, the Kingdom of the Franks was partitioned, and Gontrand inherited a significant portion, establishing his capital at Orléans. While he ruled over a quarter of the Frankish realm, his domain encompassed what was commonly referred to as the Kingdom of Burgundy after its absorption by his father. Gontrand's name itself, "Gontrand," denotes "War Raven," a fitting appellation for a ruler who navigated complex political landscapes and military campaigns.

Despite an initial period characterized by intemperance, Gontrand underwent a profound personal transformation, dedicating his later years to repentance and governing according to Christian principles. This shift in character earned him the enduring moniker "good king Gontrand" from contemporary chronicler St. Gregory of Tours. Throughout his reign, Gontrand was celebrated for his benevolence and his commitment to social welfare, particularly during times of widespread hardship like plague and famine. He acted as a protector of the oppressed, a caregiver to the sick, and a tender parent to his subjects. His rule was marked by a strict yet just enforcement of law, tempered by a remarkable readiness to forgive personal offenses, including multiple assassination attempts against him. A devout patron of the Catholic Church, Gontrand munificently established and funded numerous churches and monasteries, solidifying his legacy as a deeply pious and compassionate monarch. His posthumous recognition as a Christian saint underscores his lasting impact and the veneration he received from his people.

2. Early Life and Accession

Gontrand's early life and the circumstances surrounding his rise to power are integral to understanding his subsequent reign.

2.1. Birth and Family

Born around 532 in Soissons, Gontrand was a key figure within the Merovingian dynasty, the ruling family of the Franks. His parents were Chlothar I, the influential King of the Franks who managed to reunify the Frankish realm, and Ingunda. As the third-eldest son, and the second-eldest who survived to inherit territory, Gontrand was positioned within a large and often contentious royal family. His relationships with his siblings, notably Charibert I, Sigebert I, and Chilperic I, would define much of his political career, characterized by both alliances and bitter conflicts over territorial control and influence.

2.2. Accession to the Throne

The death of Gontrand's father, Chlothar I, in 561 AD, triggered a customary but often turbulent division of the expansive Kingdom of the Franks among his surviving sons. Gontrand, along with his brothers Charibert I, Sigebert I, and Chilperic I, each inherited a quarter of the realm. Gontrand's specific inheritance led to him being crowned King of Orléans, establishing Orléans as his capital. This portion of the Frankish Kingdom also encompassed much of the territory that had formerly constituted the independent Kingdom of Burgundy, which Chlothar I had successfully incorporated into the Frankish domain. Thus, while Orléans served as his administrative center, his influence extended over the Burgundian lands, making him, in essence, the King of Burgundy, albeit as a vassal within the broader Frankish sphere. This division of the kingdom, while traditional, frequently led to internal strife and power struggles among the royal siblings.

3. Reign and Political Activities

Gontrand's reign was characterized by a complex interplay of internal dynastic conflicts, efforts to maintain domestic stability, and engagement in military campaigns and diplomatic relations with neighboring powers.

3.1. Internecine Conflicts

The Merovingian dynasty was frequently plagued by intense internecine conflicts, and Gontrand's rule was no exception. Following the death of his elder brother, Charibert I, in 567, Charibert's lands, including the important city of Paris, were divided among the three surviving brothers: Gontrand, Sigebert I (King of Austrasia), and Chilperic I (King of Soissons, later Neustria). Initially, they agreed to hold Paris in common, an attempt at shared governance that often proved fragile. The political maneuvering extended even to family matters; Charibert's widow, Theudechild, proposed marriage to Gontrand, the eldest remaining brother. However, a council convened in Paris as early as 557 had explicitly forbidden such unions as incestuous, reflecting the nascent influence of Christian doctrine on Frankish law. Consequently, Gontrand, though perhaps unwillingly, housed her safely in a monastery in Arles rather than entering into a prohibited marriage.

By 573, Gontrand found himself embroiled in a civil war with his brother Sigebert I. In a strategic move, Gontrand initially sought the aid of their third brother, Chilperic I. However, Gontrand later reversed his allegiance, a decision often attributed to the treacherous character of Chilperic, as noted by St. Gregory. This shift in loyalty led to Chilperic's retreat. Gontrand thereafter remained a staunch ally of Sigebert, and later, of Sigebert's wife, Brunhilda, and their sons, an alliance that persisted until Gontrand's death. When Sigebert was assassinated later in 575, Chilperic seized the opportunity to invade Austrasia. In response, Gontrand dispatched his most formidable general, Mummolus, widely regarded as the greatest military leader in Gaul at the time. Mummolus successfully defeated Chilperic's general Desiderius, compelling the Neustrian forces to withdraw from Austrasia and securing the future of Sigebert's line.

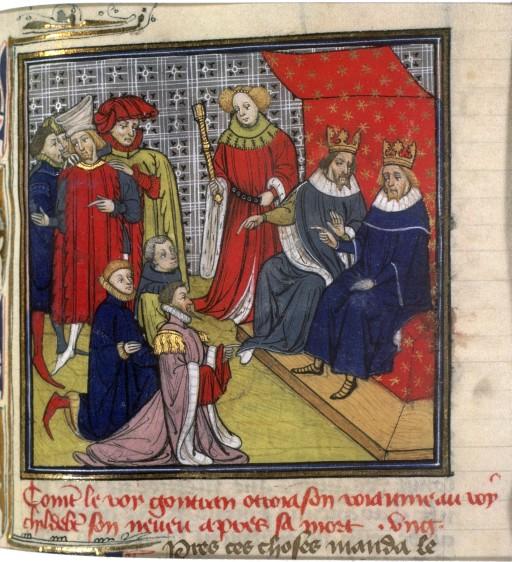

A personal tragedy further complicated Gontrand's dynastic concerns. In 577, his two surviving sons, Chlothar and Chlodomer, died of dysentery. This loss led Gontrand to adopt his nephew, Childebert II (Sigebert's son), as his son and heir, thereby solidifying his alliance with Austrasia and ensuring the continuation of a strong, unified front against Chilperic. Despite this adoption, Childebert II did not always demonstrate unwavering loyalty to his uncle. In 581, Chilperic launched new offensives, seizing many of Gontrand's cities. By 583, Chilperic had even forged an alliance with Childebert II, jointly attacking Gontrand. This prompted Gontrand to seek peace with Chilperic, leading to Childebert's withdrawal. In 584, Gontrand retaliated for Childebert's infidelity by invading his territory, capturing cities like Tours and Poitiers. However, his campaign was interrupted when he had to attend the baptism of his other nephew, Chlothar II, who now ruled in Neustria. The planned baptism, meant to take place in Orléans on July 4, the feast of St. Martin of Tours, did not occur as intended, and Gontrand instead diverted his forces to invade Septimania, though peace was soon established.

A significant development in 587 was the Treaty of Andelot, concluded between Gontrand and Childebert II in Trier. This treaty, a cornerstone of stability in the volatile Frankish realm, also involved Brunhilda (Sigebert's widow), Chlodosind (Childebert's sister), Faileuba (Childebert's queen), Magneric (Bishop of Trier), and Ageric (Bishop of Verdun). This pact, representing a formalization of their alliance, endured and provided a period of relative peace until Gontrand's death.

3.2. Domestic Policy and Rebellions

Gontrand's approach to governance was deeply influenced by his strong Christian convictions, particularly after a period of personal reflection and repentance. He strived to rule justly and benevolently, maintaining a reputation as a protector of the oppressed and a compassionate leader.

He dedicated himself to enforcing the law strictly but fairly, without regard for social status or personal favoritism, ensuring domestic order and justice for all. Despite this stern adherence to legal principles, Gontrand was remarkably forgiving of personal offenses, even surviving two assassination attempts against his life, which he chose to pardon. This blend of justice and mercy defined his rule. During times of severe hardship, such as outbreaks of plague and famine, Gontrand demonstrated immense generosity, providing aid and care to the sick and impoverished. St. Gregory of Tours famously lauded him as a "tender parent" to his subjects, highlighting his benevolent and caring nature.

Gontrand's reign also faced internal threats, most notably the rebellion of Gundowald in 584 or 585. Gundowald claimed to be an illegitimate son of Chlothar I and proclaimed himself king, gaining control of several major cities in southern Gaul, including Poitiers and Toulouse, which were part of Gontrand's domain. Gontrand swiftly moved against him, publicly dismissing his claims as those of a mere "miller's son named Ballomer." Gundowald eventually fled to Comminges, where Gontrand's army besieged the citadel. Though unable to capture the stronghold directly, Gontrand did not need to; Gundowald's own followers, facing an untenable situation, betrayed him and handed him over to Gontrand's forces, leading to his execution.

Another significant domestic challenge arose in 590, when Gontrand's niece, Basina, instigated a rebellion at the Holy Cross abbey of Poitiers. Gontrand, with the crucial aid of many of his bishops, successfully quelled this uprising, reaffirming his authority and demonstrating the close relationship between his secular power and the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

3.3. Military Campaigns and Foreign Relations

Beyond internal politics, Gontrand engaged in various military campaigns and diplomatic efforts to secure and expand his kingdom's influence.

One notable area of conflict was with the Bretons. In 587, Gontrand successfully compelled obedience from Waroch II, the Breton ruler of the Vannetais. He forced Waroch to renew an oath originally made in 578 and demanded 1,000 solidi in compensation for raids on the Nantais region. However, by 588, this compensation had still not been paid, as Waroch had ambiguously promised it to both Gontrand and Chlothar II, who likely held suzerainty over Vannes. In 589 or 590, Gontrand escalated the situation by sending an expedition against Waroch, led by his generals Beppolem and Ebrachain. These two commanders were mutual enemies, with Ebrachain also being an adversary of Fredegund (Chilperic's wife), who ironically sent Saxons from Bayeux to aid Waroch. Beppolem fought valiantly alone for three days before falling in battle. Subsequently, Waroch attempted to flee to the Channel Islands, but Ebrachain intercepted and destroyed his ships, forcing him to accept a peace agreement. This new accord required the renewal of the oath and the surrender of a nephew as a hostage. Despite these efforts, the Bretons largely maintained their independent spirit and continued to resist Frankish authority effectively.

In 589, Gontrand initiated a final military advance on Septimania, a region in southern Gaul. However, this campaign proved unsuccessful, yielding no lasting gains for the Frankish kingdom. In addition to these major actions, Gontrand continuously fought against various barbarian groups who threatened the borders and stability of his realm, demonstrating his ongoing commitment to defending his kingdom from external menaces.

4. Personal Life and Character

Gontrand's personal life reflects a journey of self-reflection and transformation, ultimately shaping his enduring reputation as a pious and benevolent monarch.

4.1. Marriages and Children

King Gontrand had three significant marital relationships during his lifetime, each with its own complexities and tragic outcomes regarding his succession.

His first union was with a concubine named **Veneranda**, who was a slave belonging to one of his people. From this relationship, Gontrand had a son named **Gundobad**. After this, Gontrand arranged for Gundobad to be sent to Orléans, perhaps as a means of establishing him within the royal court or preparing him for a future role.

Subsequently, Gontrand married **Marcatrude**, the daughter of a nobleman named Magnar. Marcatrude's jealousy became a destructive force, particularly directed towards Gundobad. According to historical accounts, she orchestrated Gundobad's death by poisoning his drink. The chronicler St. Gregory of Tours recounts that in divine judgment, Marcatrude soon lost her own son and incurred the king's deep hatred. Consequently, she was dismissed by Gontrand and died shortly thereafter.

After Marcatrude's dismissal and death, Gontrand married his third wife, **Austregilde**, also known by the name Bobilla. This marriage produced two sons for Gontrand: **Chlothar** (the elder) and **Chlodomer** (the younger). Tragically, both Chlothar and Chlodomer died young in 577 AD from dysentery, leaving Gontrand without a direct male heir from his legitimate marriages. This succession crisis compelled him to adopt his nephew, Childebert II, as his heir, altering the course of the Frankish succession.

4.2. Piety and Governance

Gontrand's reign is notably marked by a significant personal transformation. While he experienced a "period of intemperance" in his earlier life, he was later overcome with profound remorse for his past sins. This introspection led him to dedicate his remaining years to fervent repentance, not only for himself but also on behalf of his nation. His path to atonement involved rigorous fasting, prayer, and weeping, as he offered himself completely to God. This remarkable shift in character profoundly influenced his approach to governance.

Throughout the remainder of his prosperous reign, Gontrand made a concerted effort to rule strictly by Christian principles. St. Gregory of Tours, a contemporary and highly regarded chronicler of the period, frequently lauded him as "good king Gontrand." Gregory's accounts depict Gontrand as a compassionate and just ruler, highlighting his role as a staunch protector of the oppressed. He was known for being a diligent caregiver to the sick and demonstrated a tender, paternal affection towards his subjects. His generosity was particularly evident during severe crises such as outbreaks of plague and periods of famine, when he freely distributed his wealth to alleviate suffering.

Gontrand upheld the law with unwavering strictness and justice, ensuring that legal enforcement was applied fairly to all, regardless of their social standing. Despite his strictness, he possessed a remarkable capacity for forgiveness, readily pardoning offenses committed against him personally, including two documented assassination attempts. His deep piety was also manifested in his munificent patronage of the Church; he extensively built and generously endowed numerous churches and monasteries throughout his kingdom. St. Gregory further attributed many miracles to King Gontrand, both during his life and after his death, with Gregory himself claiming to have witnessed some of these miraculous events, solidifying Gontrand's reputation as a divinely favored ruler.

5. Death and Veneration

Gontrand's death marked the end of a significant reign, immediately followed by his popular veneration as a saint.

5.1. Death

King Gontrand died in Chalon-sur-Saône on March 28, 592 AD. His death brought an end to a 31-year reign characterized by both political turmoil and significant personal and governmental reform. As he had no surviving direct male heirs from his marriages, his nephew, Childebert II of Austrasia, whom Gontrand had previously adopted, succeeded him to the throne. Gontrand was laid to rest in the Church of Saint Marcellus, a religious edifice which he himself had founded and generously endowed in Chalon-sur-Saône. His burial in a church he established underscores his deep devotion and patronage of the Christian faith.

5.2. Canonization and Legacy

Immediately following his death, Gontrand's subjects, recognizing his profound piety and benevolent rule, proclaimed him a saint. This popular acclamation was later formalized, and the Catholic Church officially recognizes him as Saint Gontrand, celebrating his feast day annually on March 28, the anniversary of his death.

His legacy is one of a ruler who, despite the violent and often ruthless political landscape of the Merovingian era, became known for his justice, mercy, and profound Christian faith. The preservation of his relics, particularly his skull, is a testament to the enduring reverence for him. Centuries later, during the upheaval of the 16th century, Huguenots-Protestant reformers who were often hostile to Catholic veneration of saints-desecrated his tomb and scattered his ashes. However, his skull miraculously remained untouched in their fury. This relic is now carefully preserved within a silver case in Chalon-sur-Saône, serving as a tangible connection to "good king Gontrand" and a symbol of his enduring spiritual and historical significance.

6. Historical Assessment

Gontrand's reign is remembered for its unique blend of political acumen and a deep, transformative piety, leading to a largely positive historical assessment.

6.1. Contributions and Positive Aspects

Gontrand's reign is distinguished by numerous positive contributions that solidified his reputation as a benevolent and effective ruler. Unlike many of his contemporary Merovingian kings, who were often characterized by ruthless ambition and internecine warfare, Gontrand cultivated an image of profound "fraternal love"-a quality explicitly noted by the chronicler St. Gregory of Tours as lacking in his brothers. This compassion extended to his subjects, whom he viewed as a "tender parent," consistently prioritizing their well-being.

His commitment to social welfare was particularly evident during times of widespread distress. During devastating outbreaks of plague and periods of severe famine, Gontrand was remarkably generous with his personal wealth, ensuring that the sick received care and the impoverished were relieved of their suffering. This active role in alleviating hardship contrasted sharply with the more detached or exploitative approaches of other rulers.

Furthermore, Gontrand was a steadfast supporter of the Catholic Church. He made significant financial contributions and took personal initiative in the construction and endowment of numerous churches and monasteries across his kingdom. This patronage was not merely a political act but stemmed from his deep personal piety and his belief in governing according to Christian principles. His efforts strengthened the Church's role in society and fostered a sense of moral order within his realm. His reputation as "good king Gontrand," as consistently described by St. Gregory of Tours, reflects a ruler who genuinely sought to embody Christian virtues in his governance, acting as a protector of the oppressed and a just enforcer of the law, even while demonstrating a remarkable capacity for forgiveness against those who wronged him personally.

6.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his widely lauded reputation as "good king Gontrand," his rule was not without its criticisms and controversial aspects, particularly concerning his earlier life and the volatile political environment he inherited.

Early in his life, Gontrand experienced what historians describe as a "period of intemperance." While the specific details of this period are not extensively elaborated upon, it suggests a phase of personal conduct that later caused him significant remorse and led to his renowned repentance. This transformation, while highlighting his capacity for moral growth, implicitly acknowledges a less virtuous past.

Moreover, Gontrand operated within a brutal political landscape where assassination attempts were a grim reality of royal life. He personally survived at least two such attempts, a testament to the constant dangers faced by Merovingian monarchs, even those known for their benevolence. These incidents underscore the pervasive intrigue and violence that permeated the Frankish court, suggesting that Gontrand's reign, despite his efforts towards justice and piety, was never entirely free from threat or moral compromise inherent in the struggle for power. His decision to pardon these attempts, rather than retaliate with severity, stands as a remarkable aspect of his character, reinforcing his image as a merciful ruler while simultaneously revealing the continuous challenges to his authority and personal safety.