1. Early Life and Background

George Monck's early life was shaped by his family's declining fortunes and the prevailing military landscape of the early 17th century, leading him to pursue a military career abroad.

1.1. Birth and Family

George Monck was born on 6 December 1608 at Potheridge, a family estate near Merton in Devon, England. He was the second son of Sir Thomas Monck (1570-1627) and Elizabeth Smith. His mother was the daughter of Sir George Smith, a wealthy merchant who served three times as Mayor of Exeter and owned twenty-five manors in the surrounding area.

The Monck family, though one of the oldest in Devon, faced financial difficulties. Sir George Smith allegedly failed to pay his daughter Elizabeth's promised dowry, leading to expensive legal disputes with Sir Thomas Monck. These financial troubles culminated in Sir Thomas's imprisonment for debt in 1625, where he remained until his death two years later. George Monck had an elder brother, Thomas (died 1647), and a younger brother, Nicholas Monck (1609-1661), who later became Bishop of Hereford and Provost of Eton College. His aunt, Grace Smith, was married to Sir Bevil Grenville, who died at the Battle of Lansdown in 1643 during the English Civil War. Sir Bevil's son, John Grenville, George Monck's cousin, significantly benefited from Monck's influence during the Restoration.

1.2. Education and Early Influences

Becoming a professional soldier and naval officer was a common career choice for younger sons of impoverished gentry in the early 17th century. His formative years included an incident in late 1626 when he and his brother Thomas assaulted Nicholas Battyn, the Undersheriff responsible for their father's imprisonment for debt. This act led to Monck's arrest for attempted murder and may have influenced his decision to seek a military career abroad.

2. Early Military Career (Pre-1641)

Monck's early military career saw him serve in various European campaigns, including in the highly regarded Dutch States Army, before his return to England and involvement in the Bishops' Wars.

2.1. Dutch Service

Monck began his military career in 1625, serving as an ensign in a company commanded by his cousin, Sir Richard Grenville, during the failed Cádiz expedition (1625) against Spain. The following year, in July 1627, he participated in the equally disastrous expedition against St Martin-de-Ré, an attempt to aid French Huguenots besieged in La Rochelle during the Anglo-French War (1627-1629).

He spent most of the next decade, from 1629 to 1638, serving in the Dutch States Army. At the time, the Dutch army was highly regarded for its military prowess due to its successes in the Eighty Years' War against Habsburg Spain. Many officers who later fought in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, such as Sir Thomas Fairfax and Sir Philip Skippon, also gained experience in the Dutch service. During the capture of Maastricht in 1632, Monck served in a regiment commanded by the Earl of Oxford, who was killed in the final assault. Monck then served under George Goring and, by 1637, had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He played a decisive role in the storming of Breda, a significant Dutch victory and one of the last major actions of the war. After a dispute with the civil authorities of Dordrecht, he resigned his commission and returned to England in 1638.

2.2. Return to England and Bishops' Wars

Upon his return to England, Monck obtained a position as lieutenant colonel in a regiment raised by Mountjoy Blount, 1st Earl of Newport, who was also Master-General of the Ordnance. He was deployed during the Bishops' Wars against Scotland in 1639 and 1640. Monck was one of the few English officers to emerge with credit from the Battle of Newburn in 1640, where he successfully saved the English artillery from capture. However, due to a lack of funds, the army was subsequently disbanded, leaving Monck unemployed for the following year.

3. Wars of the Three Kingdoms

This period saw Monck's involvement in the Irish Rebellion and the English Civil War, where he initially served the Royalists before being captured and later transitioning to the Parliamentarian side.

3.1. Royalist Service and Captivity

Following the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1641, the Parliament of England authorized the recruitment of a Royal Army to suppress it. Monck was appointed colonel of a regiment raised by his distant relative, Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester, which landed in Dublin in January 1642. He served under James Butler, Earl of Ormond, the Royalist commander in Ireland. Over the next eighteen months, Monck campaigned against rebel strongholds in Leinster, where he was allegedly responsible for several massacres in County Kildare. He also participated in the Battle of New Ross in March 1643.

However, the outbreak of the First English Civil War in August 1642 meant that Ormond could no longer receive reinforcements or funds from England. By mid-1643, the Catholic Confederacy controlled most of Ireland, with the exception of Ulster, Dublin, and Cork City. Most of Ormond's officers, including Monck, advocated for the Irish Army to remain neutral between the Parliamentarians and Royalists. However, Charles I was keen to use these troops to aid his war effort in England. In September 1643, Ormond agreed to a truce, known as the "Cessation," with the Confederacy. Monck, among others, initially refused to swear allegiance to the King and was sent by Ormond as a prisoner to Bristol. He eventually agreed to support the Royalists but was captured by Parliamentarian forces at the Battle of Nantwich in January 1644. Due to his recognized experience and ability, Monck remained imprisoned for the next two years, during which he authored a military manual titled Observations on Military and Political Affairs.

3.2. Transition to Parliamentarian

Monck was released from captivity in 1646, following Charles I's surrender. He accepted an appointment in one of the regiments dispatched to Ireland by Parliament as reinforcements. In September 1647, he was appointed Parliamentarian commander in Eastern Ulster. Monck demonstrated his loyalty to Parliament by refusing to participate in the Second English Civil War and required all his officers to sign a declaration of support for Parliament.

However, his position in Ulster became precarious after the execution of Charles I in January 1649, as the region was dominated by Scots Presbyterian settlers supported by a Covenanter army under Robert Monro. These Scots objected to the English executing their king without consultation, viewing monarchy as divinely ordained and the execution as sacrilegious. Consequently, they defected to the Royalist-Confederate alliance led by Ormond. In a desperate move, Monck agreed to a secret truce with Eoghan Ó Néill, the Catholic leader in Ulster, a fact he did not disclose to Parliament until May. Recalled to London, he was reprimanded by a Parliamentary committee, though they privately acknowledged the desperate circumstances that necessitated his actions.

Despite some mistrust due to his former Royalist allegiance, Oliver Cromwell gave Monck command of a regiment in the Anglo-Scottish War (1650-1651). Monck's regiment fought at the Battle of Dunbar and later stormed Dundee, an action during which approximately 800 civilians were reportedly killed.

4. Commonwealth and Protectorate Period

During the Commonwealth and Protectorate, Monck served as a key military commander in Scotland and as a General at Sea, demonstrating his loyalty to Oliver Cromwell.

4.1. Scottish Commander

Throughout the Protectorate, Monck remained loyal to Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell appointed him military commander in Scotland, a position he held until February 1652. Monck became seriously ill at that time and retired to Bath to recover.

In April 1653, Cromwell dissolved the Rump Parliament, and in June, Monck was nominated MP for Devon in Barebone's Parliament. Although the First Anglo-Dutch War did not formally conclude until the Treaty of Westminster in February 1654, Monck was recalled and dispatched to Scotland to suppress the Royalist Glencairn's rising. Appointed military commander and Commander-in-Chief of Scotland from April 1654 to February 1660, he employed the ruthless tactics he had demonstrated in previous assignments, and by the end of 1655, the country had been pacified. He retained this position for the next five years, demonstrating his loyalty by removing any officers who expressed opposition to government policy and arresting religious dissidents.

4.2. First Anglo-Dutch War

Due to his expertise in utilizing artillery and the shortage of naval personnel caused by the revolution, Monck was appointed a General at sea in November 1652, alongside Robert Blake and Richard Deane, at the outbreak of the First Anglo-Dutch War. He fought in the crucial naval battles of 1653, including Portland, the Gabbard, and Scheveningen. In the Battle of Portland, he took command after Robert Blake was seriously wounded. Monck's forces defeated the Dutch fleet under Admiral Maarten Tromp at the Battle of the Gabbard and again at the Battle of Scheveningen, where Tromp was killed. The war concluded with the Treaty of Westminster in 1654, establishing England's naval superiority.

During his tenure as General at Sea (1652-1653), Monck, along with Blake and William Penn, actively pursued naval reforms. They adopted the line-ahead battle formation, a tactic where ships formed a single column to deliver concentrated broadsides, which proved effective at the Battle of the Gabbard. This formation was later adopted by the Dutch and became a fundamental naval strategy worldwide. The Anglo-Dutch Wars also solidified England's maritime strategy, emphasizing control of the Mediterranean Sea and securing command of the seas, objectives that would become crucial for the future British Royal Navy.

4.3. Role during the Protectorate

Monck remained a staunch supporter of Cromwell. When Oliver Cromwell died in September 1658, Monck transferred his support to Cromwell's son, Richard Cromwell, who was appointed Lord Protector. Monck's support for the Protectorate was based on his personal regard for its leader.

5. The Restoration

Monck played a pivotal and crucial role in the English Restoration, leading to significant political negotiations and receiving substantial titles and rewards from Charles II.

5.1. Crucial Role in Realizing the Restoration

The Third Protectorate Parliament, elected in January 1659, was dominated by moderate Presbyterians like Monck and Royalist sympathizers, whose primary objective was to reduce the power and expense of the military. In April, army radicals, led by John Lambert and Charles Fleetwood, dissolved Parliament and forced Richard Cromwell's resignation. This new regime, sometimes known as the Wallingford House party, abolished the Protectorate, reseated the Rump Parliament (which Cromwell had dismissed in 1653), and began removing officers and officials of suspect loyalty, including many serving in Scotland.

Monck was largely left in place because rumors of another Royalist uprising made it strategically preferable to retain him. Both his cousin, John Grenville, and his brother, Nicholas, were connected with the Royalist underground. In July 1659, Nicholas brought Monck a personal appeal from Charles II, asking for his assistance and offering up to 100.00 K GBP per year for his help. When Booth's Uprising broke out in August 1659, Monck considered joining it, but the revolt collapsed before he had time to commit himself. In October, the Wallingford House group dismissed the Rump, only to be forced to reinstate it in early December.

By the end of 1659, England appeared to be drifting into anarchy, with widespread demands for new elections and an end to military rule. Monck declared his support for the Rump against the Republican faction led by Lambert, while also coordinating with Sir Theophilus Jones, a former colleague in Ireland who seized Dublin Castle in late December. Simultaneously, Monck marched his army from Scotland to the English border, supported by a force raised by former New Model Army commander Sir Thomas Fairfax. Outnumbered and unpaid, Lambert's troops dispersed, and on 2 February 1660, Monck entered London. In April, elections were held for a Convention Parliament.

5.2. Political Negotiations and Influence

While Monck's backing was essential to the English Restoration, modern historians debate whether his actions were initiated by him or if he simply followed the overwhelming majority opinion, which by then favored reinstating the monarchy. Although he was elected MP for Devon, observers noted his limited interest in politics, and his lack of a regional power base in England, coupled with the proposed reduction of the army, worked against his future political influence.

Nevertheless, the Declaration of Breda, issued by Charles II on 4 April 1660, was largely based on Monck's recommendations. It promised a general pardon for actions committed during the civil wars and English Interregnum, with the exception of the regicides; retention by current owners of property purchased during the same period; religious toleration; and payment of arrears to the army. Based on these terms, Parliament resolved to proclaim Charles king and invited him to return to England. Charles left the Dutch Republic on 24 May and entered London five days later. Monck met Charles II upon his return, successfully realizing the Restoration without major upheaval.

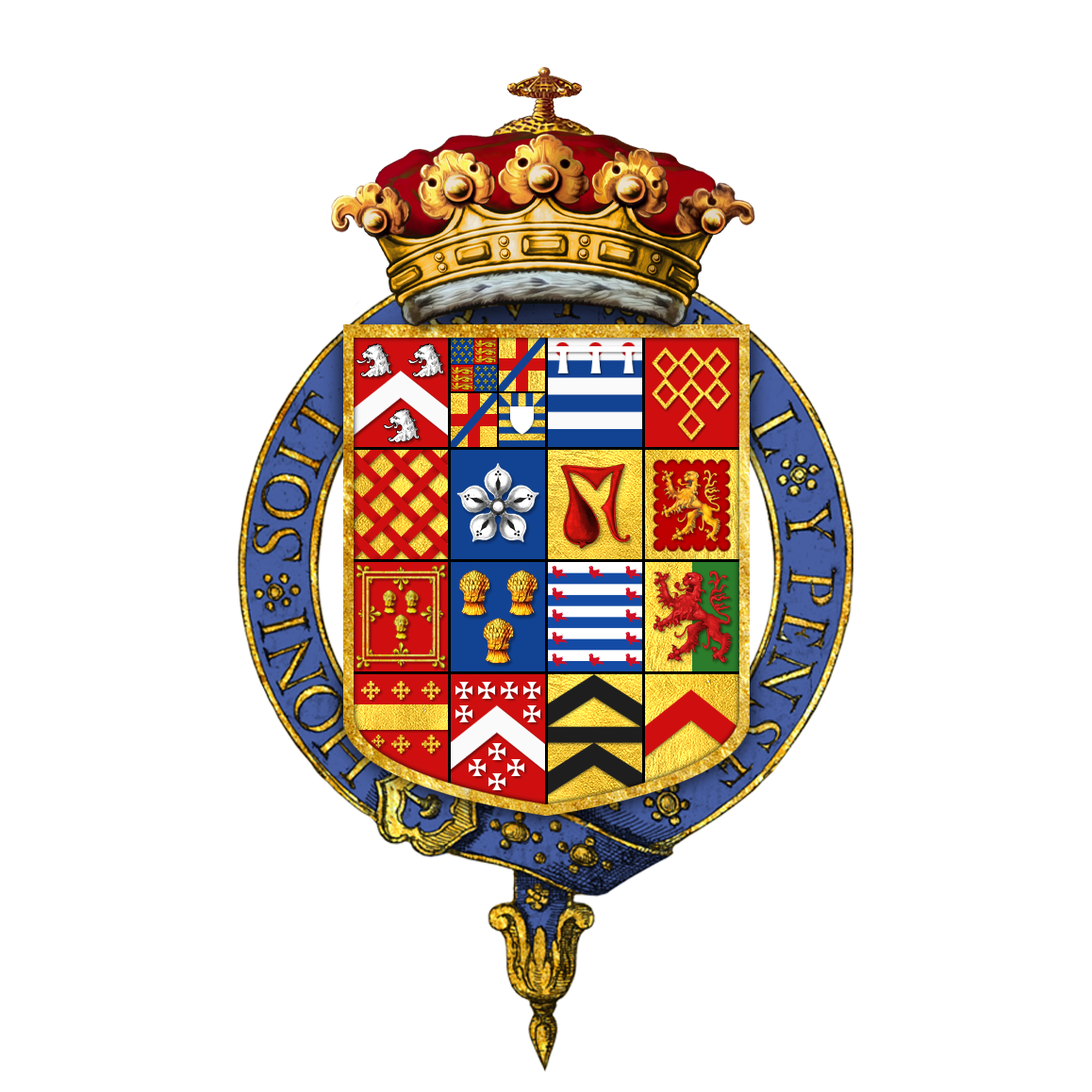

5.3. Titles and Rewards

In recognition of his vital services, Charles II bestowed significant titles, honors, and financial rewards upon Monck. In July 1660, Monck was created Duke of Albemarle (a title he held until his death in 1670) and appointed to the Privy Council. He also received the former Palace of Beaulieu, lands in Ireland and England worth 7.00 K GBP per year, and an annual pension of 700 GBP.

He was granted various important offices, including Lord Lieutenant of Devon and Custos Rotulorum of Devon (both held from 1660 to 1670). He was also appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Forces (1660-1670) and held the rank of Captain General. Although initially appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland (June 1660-February 1662), Monck fell seriously ill in August 1661 and was replaced by Ormond, being compensated with the additional office of Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex (1662-1670). He also held the position of Master of the Horse (1660-1668) and was made a Knight of the Garter.

Monck also secured significant positions for his dependents and connections. His cousin, John Grenville, became Earl of Bath, while his brother, Nicholas Monck, was appointed Bishop of Hereford. His cousin, William Morice, became Secretary of State for the Northern Department, and his brother-in-law, Thomas Clarges, was appointed Commissary General of Musters.

In 1663, Monck was selected as one of eight proprietors of the Province of Carolina in North America, which now encompasses the modern US states of South Carolina and North Carolina. The Albemarle Sound in North Carolina is named after his ducal title. He also became a shareholder in the Royal African Company, which was established to challenge Dutch control of the Atlantic slave trade and contributed significantly to the commercial tensions that led to the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

Monck's mounted guard, known as Monck's Life Guards, became the 2nd/Queen's Troop of the Life Guards regiment. In 1661, his infantry regiment became the Household Infantry Regiment, later officially named the Coldstream Guards, a name it retains to this day, with Monck serving as its Colonel from 1650 to 1670.

6. Later Career and Public Office

After the Restoration, Monck continued to serve the Crown in various capacities, including during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and in administrative roles, despite his declining health.

After 1660, due to a combination of illness and a lack of interest in politics, Monck generally avoided front-line political involvement, focusing instead on maximizing his personal wealth. His wife, Anne Clarges, gained a reputation for selling offices, a common practice at the time, though her humble origins likely fueled resentment. The diarist Samuel Pepys famously described her as a "homely, plain dowd" and a "filthy woman," though Pepys's views were influenced by the rivalry between Monck and his own cousin, Edward Montagu, for control of the Admiralty.

6.1. Second Anglo-Dutch War

Monck returned to active military command during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, which began in 1665. The conflict was supported by Monck and other government investors in the Royal African Company. Command of the fleet was initially given to James, Duke of York, with Sandwich as his deputy, while Monck took over administrative duties at the Admiralty.

In 1666, Monck shared command of the English fleet with Prince Rupert. During the Four Days' Battle in June, Rupert's squadron was detached to intercept French reinforcements, leaving Monck to face the superior Dutch fleet led by Michiel de Ruyter. Despite heavy losses, Monck's forces fought bravely and managed to inflict significant damage on the Dutch, forcing both sides to withdraw. The English achieved a victory in the subsequent St. James's Day Battle in July, though the reported success was somewhat exaggerated. In August, Monck's forces also conducted raids on Dutch merchant shipping, notably Holmes's Bonfire.

6.2. Period of the Great Plague and Great Fire of London

Monck gained considerable popularity for remaining in London throughout the 1665 Great Plague of London, when most of the government and wealthier citizens fled to Oxford. His presence helped maintain public confidence and order during the crisis.

In September 1666, following the devastating Great Fire of London, Monck was recalled from naval command by Charles II to help maintain order amidst the chaos. His leadership was crucial in organizing relief efforts and restoring stability to the capital.

6.3. Administrative and Other Public Offices

The 1666 campaign was Monck's last active military command. The English fleet faced severe financial constraints, leading to its laying up, which culminated in the humiliating Raid on the Medway by the Dutch fleet in June 1667. Although this raid ended the war, Monck was one of the few figures to escape censure by Parliament for the disaster.

In 1667, Monck was appointed First Lord of the Treasury (a position he held until his death in 1670). However, he was by then suffering from severe edema, which significantly limited his ability to attend meetings and perform his duties. The practical work of the Treasury was largely delegated to a committee.

7. Personal Life

This section details George Monck's marriage and family life.

7.1. Marriage and Family

In January 1653, George Monck married Anne Clarges (1619-1670), the daughter of a London farrier and the widow of Thomas Radford. The legality of their marriage was later questioned as Radford's death was not officially confirmed until a year after their wedding. Anne's brother, Thomas, a committed Royalist, was knighted after the Restoration and had a long career in Parliament. George and Anne had one son who survived into adulthood, Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle (1653-1688).

8. Death and Legacy

This section covers the circumstances of George Monck's death, his burial, and his lasting historical impact.

8.1. Circumstances of Death

In his final years, George Monck's health steadily declined due to severe edema. He died on 3 January 1670, at the age of 61. His wife, Anne, followed him in death just three weeks later.

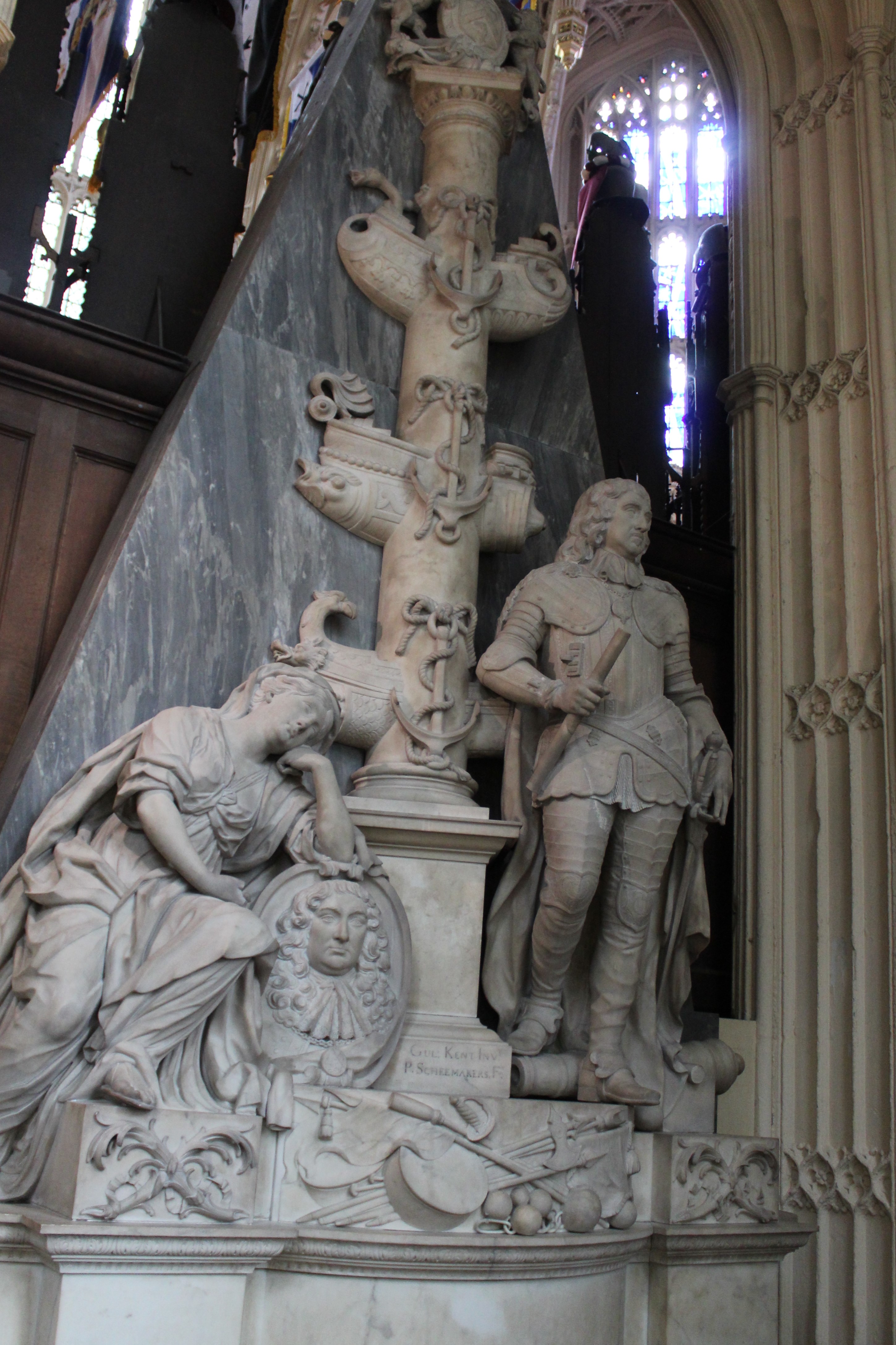

8.2. Burial and Commemoration

Monck was buried in Westminster Abbey, a testament to his significant contributions to England. Some years after his death, a monument designed by William Kent and Peter Scheemakers was erected in the Abbey in his honor. A ballad titled On the Death of His Grace, the Duke of Albemarle was composed to commemorate him.

8.3. Historical Evaluation and Impact

George Monck is historically evaluated as a pivotal figure in English history, primarily for his decisive role in the English Restoration. His actions brought stability to England after years of civil war and the tumultuous English Interregnum, facilitating the peaceful return of the monarchy. His military career was marked by both strategic brilliance and a willingness to employ ruthless tactics to achieve his objectives, particularly in Ireland and Scotland.

His contributions to naval reform during the First Anglo-Dutch War, particularly the adoption of the line-ahead battle formation, had a lasting impact on naval warfare worldwide. Despite his shifting allegiances during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, his ultimate commitment to order and stability made him indispensable during the period of political uncertainty following Cromwell's death. The Monck family line and the Dukedom of Albemarle became extinct upon the death of his only son, Christopher Monck, in 1688, who left no children. The Earldom of Albemarle was later re-created for Arnold van Keppel. While James II attempted to revive the Dukedom of Albemarle for his illegitimate son, Henry FitzJames, in 1696, this was a Jacobite peerage without practical effect and became extinct upon Henry's death in 1702.