1. Background

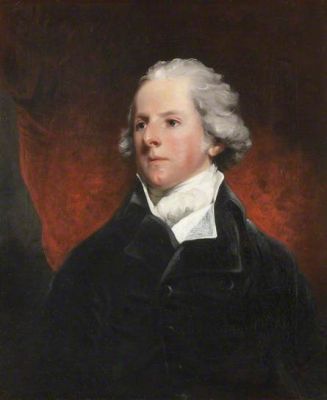

George Granville Leveson-Gower's early life was marked by his aristocratic lineage and a comprehensive education, preparing him for a life of public service and land management.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Born on 9 January 1758 in Arlington Street, London, George Granville Leveson-Gower was the eldest son of Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Marquess of Stafford, and his second wife, Lady Louisa Egerton. Lady Louisa was the daughter of Scroop Egerton, 1st Duke of Bridgewater. His half-brother was Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Granville.

Leveson-Gower received his education at Westminster School and later at Christ Church, Oxford, where he earned his Master of Arts (MA) degree in 1777. Following his university studies, he embarked on a Grand Tour, a traditional journey through Europe undertaken by young aristocrats to broaden their education and cultural experience.

2. Political Career

Leveson-Gower's political career spanned several decades, encompassing roles as a Member of Parliament, a diplomat, and a peer in the House of Lords, where he eventually attained the highest rank of Duke.

2.1. Early Parliamentary Service

Leveson-Gower began his parliamentary career as a Member of Parliament for Newcastle-under-Lyme, serving from 1779 to 1784. Although he lost his seat in the 1784 general election, he was re-elected in 1787 to represent Staffordshire, a constituency he continued to serve until 1799. In that year, he was summoned to the House of Lords through a writ of acceleration, inheriting his father's junior title of Baron Gower while his father was still alive.

2.2. Ambassador to France

Between 1790 and 1792, Leveson-Gower served as the Ambassador to France. Appointed at the age of 32 in June 1790, he found himself in a challenging diplomatic environment amidst the unfolding French Revolution. With Louis XVI under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace, Leveson-Gower was unable to engage closely with the royal family or participate in the traditional diplomatic functions at Versailles. He had no prior diplomatic experience and was considered ill-equipped to navigate the complexities of the revolutionary period, much like his predecessor, the Duke of Dorset.

His primary responsibility in Paris was to relay news from the French court back to Britain, regardless of its significance. While he reported on popular "disturbances," he demonstrated little comprehension of the broader political climate. On 10 August 1792, an insurrection led by the newly established Paris Revolutionary Commune forced the royal family from the Tuileries Palace. Three days later, Louis XVI was arrested and imprisoned in the Temple fortress. In protest, Britain severed diplomatic relations, leading to the closure of the British embassy and Leveson-Gower's removal from his diplomatic post in France. Captain George Monro replaced him to manage intelligence operations.

2.3. Later Political Career and Titles

Upon his return to Britain, Leveson-Gower declined offers for the prestigious posts of Lord Steward of the Household and Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland. However, in 1799, he accepted the office of joint Postmaster General, a position he held until 1801. He played a notable role in the downfall of Henry Addington's administration in 1804, after which he shifted his political allegiance from the Tory party to the Whig party. Despite his earlier active involvement, he largely withdrew from politics after 1807, though he later supported significant reforms such as Catholic Emancipation and the 1832 Reform Act.

In addition to his political roles, Leveson-Gower held several honorary and military appointments. On 20 September 1794, he was appointed Colonel of the new Staffordshire Regiment of Gentlemen and Yeomanry, personally commanding the Newcastle-under-Lyme Troop until his retirement in January 1800. He also served as Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire from 1799 to 1801 and Lord Lieutenant of Sutherland from 1794 to 1830. He was invested as a Privy Counsellor in 1790 and a Knight of the Garter in 1806. In 1831, as Marquess of Stafford, he served as the annual treasurer of the Royal Salop Infirmary in Shrewsbury. His ascent through the peerage culminated on 28 January 1833, when he was created Duke of Sutherland.

3. Wealth and Estates

George Granville Leveson-Gower's immense wealth and extensive landholdings positioned him as one of the richest individuals of his era, primarily due to significant inheritances and strategic land management.

3.1. Inheritance and Holdings

The Leveson-Gower family already possessed vast estates across Staffordshire, Shropshire, and Yorkshire. In 1803, Leveson-Gower significantly augmented his wealth through the inheritance of the immense estates of his maternal uncle, Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater. This inheritance included the lucrative Bridgewater Canal and a substantial art collection, which featured a significant portion of the renowned Orleans Collection. Both Leveson-Gower and his uncle had been members of the consortium that brought the Orleans Collection to London for dispersal.

The Duke of Bridgewater's will stipulated that these inherited properties would pass to Leveson-Gower's third son, Lord Francis Leveson-Gower, upon the first Duke of Sutherland's death. This inheritance brought him extraordinary wealth, leading to him being estimated as the wealthiest man of the 19th century, even surpassing Nathan Mayer Rothschild. The precise value of his estate at the time of his death remains unknown, simply categorized as "upper value." The diarist Charles Greville famously described him as a "leviathan of wealth" and "the richest individual who ever died." His rent income from his Scottish Highland properties alone saw a dramatic increase, surging from just under 55.00 K GBP to 200.00 K GBP within 13 years from 1802, a testament to the agricultural development spurred by the French Revolution and subsequent wars.

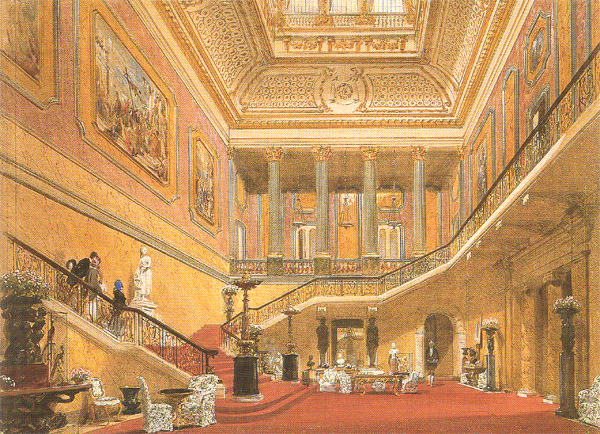

3.2. Stafford House

Following the death of the Duke of York in 1827, Leveson-Gower purchased the leasehold of Stafford House. This grand residence, now known as Lancaster House, became the principal London home for the Dukes of Sutherland until 1912, reflecting their prominent social and economic standing.

4. Sutherland Development and Highland Clearances

The management of his vast landholdings in Sutherland, Scotland, particularly the implementation of the Highland Clearances, remains the most controversial aspect of George Granville Leveson-Gower's legacy, marked by forced evictions and profound social disruption.

4.1. Estate Development and Policy

Leveson-Gower and his wife, Elizabeth Sutherland, 19th Countess of Sutherland, were central figures in the execution of the Highland Clearances, a program of "improvement" that involved the eviction of thousands of tenants and their resettlement in coastal crofts. The larger clearances in Sutherland primarily occurred between 1811 and 1820.

The rationale behind these changes was rooted in contemporary social and economic theories. Leveson-Gower, reportedly appalled by the poor living conditions of his tenants, and his wife, who had significant oversight of the estate, became convinced that subsistence farming in the interior of Sutherland was unsustainable in the long term. They believed that much higher rents could be obtained by converting the land to extensive sheep farms, thereby generating a significantly better income from the estate.

Plans for clearance had existed for some years within the Sutherland estate management, with some initial activity as early as 1772 when Lady Sutherland was a child. However, these early plans were hampered by a shortage of funds, a situation that persisted even after her marriage to Leveson-Gower. It was only after he inherited the immense wealth of the Duke of Bridgewater that these plans could proceed, with Leveson-Gower willingly investing large sums of his new fortune into the transformation of the Sutherland estate. Lady Sutherland took a keen interest in the estate, traveling to Dunrobin Castle most summers and maintaining continuous correspondence with the factor and James Loch, the Stafford estate commissioner.

In 1811, Parliament passed an Act that granted half the expenses for building roads in northern Scotland, provided that landowners covered the other half. The following year, Sutherland commenced building roads and bridges in the county, which had previously lacked such infrastructure.

4.2. Evictions and Resettlement

The process of tenant displacement was systematic and often brutal. The first wave of new clearances involved relocating families from Assynt to coastal villages, with the intention that they would take up fishing as a new livelihood.

The eviction in the Strath of Kildonan in 1813 met with significant opposition, leading to a six-week confrontation. This standoff was ultimately resolved only by calling in the army, though the estate did make some concessions to those who were evicted.

A particularly infamous incident occurred in 1814 during clearances in Strathnaver, supervised by one of the estate's factors, Patrick Sellar. To prevent houses from being reoccupied after eviction, their roof timbers were set on fire. Allegedly, an elderly, bedridden woman was still inside one of these burning houses. Although she was rescued, she died six days later. This incident led to Sellar's prosecution, initiated by Robert Mackid, a local law officer who was an enemy of Sellar. The case went to trial in 1816, and Sellar was acquitted. However, the resulting publicity was highly unfavorable to the Sutherlands. Sellar was subsequently replaced as factor, but larger clearances continued between 1818 and 1820. Despite efforts to control press coverage, in 1819, The Observer newspaper ran the damning headline: "the Devastation of Sutherland," reporting the widespread burning of roof timbers from numerous houses cleared simultaneously.

4.3. Social Impact and Criticism

The Highland Clearances under the Sutherlands had devastating consequences for the traditional Highland communities. Thousands of families were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands, disrupting centuries-old ways of life and leading to widespread poverty, displacement, and emigration. The policy, driven by economic gain from sheep farming, prioritized profit over human welfare, fundamentally altering the social fabric and demographics of the region.

The Sutherland family, particularly the Duke and Duchess, faced intense criticism for their role in these events. The phrase "the Devastation of Sutherland" encapsulates the profound negative impact. The clearances became a symbol of landlord tyranny and the human cost of agricultural "improvement." This criticism was not confined to contemporary newspaper reports; it also found expression in cultural forms. Several well-known Gaelic songs were composed specifically to mock the Duke personally. One of the most famous is Dùthaich Mhic AoidhGaelic (Mackay Country or Northern Sutherland), written by Ewen Robertson, who became known as the "Bard of the Clearances." This song, like others, condemns the Duke's actions and expresses the deep resentment and suffering of the evicted population. A verse from Dùthaich Mhic Aoidh translates to:

"First Duke of Sutherland, with your deceit,

And with your friendship with the Lowlanders,

It's in hell that you belong,

I'd rather have Judas by my side."

5. Personal Life

George Granville Leveson-Gower's personal life was intertwined with his family, particularly his marriage to Elizabeth Sutherland, which brought the vast Sutherland estates into his influence.

5.1. Marriage and Children

On 4 September 1785, George Granville Leveson-Gower married Elizabeth Sutherland, 19th Countess of Sutherland. Elizabeth was the daughter of William Sutherland, 18th Earl of Sutherland, and Mary Maxwell. Together, they had four surviving children:

- George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland (11 August 1786 - 27 February 1861), who succeeded his father as the 2nd Duke of Sutherland.

- Lady Charlotte Sophia Leveson-Gower (c. 1788 - 7 July 1870), who married Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 13th Duke of Norfolk and had issue.

- Lady Elizabeth Mary Leveson-Gower (1797-1891), who married Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster and had issue.

- Francis Leveson-Gower (later Egerton), 1st Earl of Ellesmere (1 January 1800 - 18 February 1857), who became a cabinet minister in the Tory government and was later created Earl of Ellesmere. The Bridgewater Estate, inherited by the 1st Duke, was passed in trust to Francis, his third son, in accordance with the Duke of Bridgewater's will.

Eleven years after being enfeebled by a paralytic stroke, George Granville Leveson-Gower died at Dunrobin Castle on 19 July 1833, at the age of 75. He was buried at Dornoch Cathedral. His eldest son, George, succeeded him in his titles. The Duchess of Sutherland died in January 1839, aged 73, and was also succeeded by their eldest son, George.

6. Monuments and Commemoration

Several monuments were erected in memory of George Granville Leveson-Gower, reflecting varying perspectives on his legacy and becoming focal points for historical debate, particularly in Scotland.

In Shropshire, the Lilleshall Monument was built in 1833. This 70 ft-high obelisk stands atop Lilleshall Hill, within the original estates of the Leveson family acquired after the dissolution of Lilleshall Abbey. It serves as a local landmark visible from a considerable distance. The tablet on its north face bears an inscription that reads: "To the memory of George Granville Leveson Gower, K.G. 1st Duke of Sutherland. The most just and generous of landlords. This monument is erected by the occupiers of his Grace's Shropshire farms as a public testimony that he went down to his grave with the blessings of his tenants on his head and left behind him upon his estates the best inheritance which a gentleman of England can bequeath to his son; men ready to stand by his house, heart and hand." This inscription reflects a highly positive, landlord-centric view of his character and management.

Another monument stands in the Trentham Gardens Estate in Trentham, Staffordshire. This colossal statue, designed by Winks and sculpted by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey, is mounted on a plain stone column with a tiered pedestal. It was erected in 1834 at the instigation of the second Duke, a year after his father's death.

However, the most controversial monument is a large statue, locally known as the Mannie, erected in 1837 on Ben Bhraggie near Golspie in Sutherland. Its existence has been the subject of ongoing debate due to the Duke's role in the Highland Clearances. In 1994, Sandy Lindsay, a former Scottish National Party councillor from Inverness, proposed its demolition. He later revised his plan, seeking permission from the local council to relocate the statue and replace it with plaques detailing the history of the Clearances. Lindsay suggested moving the statue to the grounds of Dunrobin Castle, after the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles declined his offer to take it. In November 2011, vandals made a failed attempt to topple the statue. A BBC news report on this incident quoted a local person who stated that few people wished the statue removed, instead viewing it as an important reminder of history. As of September 2024, the statue still stands, a stark symbol of the historical divisions and trauma associated with the Clearances.

7. Legacy and Assessment

George Granville Leveson-Gower's legacy is complex and deeply divided, marked by his immense wealth and contributions to land development, yet overshadowed by the profound human cost of the Highland Clearances.

7.1. Contributions and Positive Recognition

Despite the controversies, Leveson-Gower was recognized for certain achievements and received praise from some quarters. His efforts in building roads and bridges in Sutherland, initiated in 1812, significantly improved infrastructure in a region that had been largely undeveloped. He was also a patron of the arts, and his acquisition of the Bridgewater art collection further enriched his cultural holdings. The inscription on the Lilleshall Monument in Shropshire, describing him as "the most just and generous of landlords," reflects a perspective that viewed his land management as beneficial, particularly from the viewpoint of his English tenants who may not have experienced the same drastic changes as those in the Highlands. This suggests a perception of him as a benevolent figure within his traditional English estates.

7.2. Criticisms and Controversies

The most enduring and significant controversies associated with George Granville Leveson-Gower stem from his pivotal role in the Sutherland Clearances. These forced evictions, carried out under his and his wife's authority, led to the displacement of thousands of Highland tenants, the destruction of communities, and a profound sense of betrayal and suffering. The policy was widely condemned for its brutality and its prioritization of economic gain (through sheep farming) over human welfare.

The public reaction to the clearances was intensely negative, as evidenced by the 1819 The Observer headline, "the Devastation of Sutherland," which highlighted the widespread destruction. This historical assessment has persisted, with the Duke often being viewed as a symbol of the harsh realities of the clearances. The "Mannie" statue on Ben Bhraggie in Sutherland has become a focal point of this negative legacy, frequently subjected to vandalism and calls for its removal, reflecting the deep-seated resentment and historical trauma within the affected communities.

The cultural impact of his actions is also evident in Gaelic folk memory and song. Several well-known Gaelic songs were composed specifically to mock and condemn the Duke personally. Perhaps the most famous of these is Dùthaich Mhic AoidhGaelic (Mackay Country or Northern Sutherland), written by Ewen Robertson, who earned the epithet "Bard of the Clearances." These songs serve as powerful expressions of the anger, sorrow, and enduring criticism directed at the Duke and his family for their role in the clearances, ensuring that his controversial legacy remains a significant part of Scottish history and cultural memory.

8. Ancestry

George Granville Leveson-Gower's ancestry can be traced through several prominent noble families.

- 1. George Leveson-Gower, 1st Duke of Sutherland

- 2. Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Marquess of Stafford

- 3. Lady Louisa Egerton

- 4. John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower

- 5. Lady Evelyn Pierrepont

- 6. Scroop Egerton, 1st Duke of Bridgewater

- 7. Lady Rachel Russell

- 8. John Leveson-Gower, 1st Baron Gower

- 9. Lady Catherine Manners

- 10. Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull

- 11. Lady Mary Feilding

- 12. John Egerton, 3rd Earl of Bridgewater

- 13. Lady Jane Paulet

- 14. Wriothesley Russell, 2nd Duke of Bedford

- 15. Elizabeth Howland

- 16. Sir William Leveson-Gower, 4th Baronet

- 17. Lady Jane Granville

- 18. John Manners, 1st Duke of Rutland

- 19. Catherine Wriothesley Noel

- 20. Robert Pierrepont, of Thoresby, Nottinghamshire

- 21. Elizabeth Evelyn

- 22. William Feilding, 3rd Earl of Denbigh

- 23. Mary King

- 24. John Egerton, 2nd Earl of Bridgewater

- 25. Lady Elizabeth Cavendish

- 26. Charles Paulet, 1st Duke of Bolton

- 27. Mary Scrope

- 28. William Russell, Lord Russell

- 29. Lady Rachel Wriothesley

- 30. John Howland of Streatham

- 31. Elizabeth Child