1. Overview

George Eastman was a pioneering American entrepreneur and inventor who fundamentally transformed photography from an expensive, specialized hobby into an accessible activity for the general public. He achieved this by founding the Eastman Kodak Company and revolutionizing the photographic process with his invention of roll film. This innovation not only democratized photography but also laid the groundwork for the development of the motion picture industry, influencing early filmmakers such as Louis Le Prince, Thomas Edison, and the Lumière brothers.

Beyond his industrial achievements, Eastman was a prolific philanthropist, donating over 100.00 M USD (equivalent to more than 2.00 B USD in 2022) to various educational, healthcare, and cultural institutions. He supported institutions like the University of Rochester and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, established the Eastman School of Music and multiple dental clinics, and contributed to urban research and calendar reform. While his contributions significantly improved societal well-being and access to technology, his legacy is complex. He faced criticism for his views on race and his financial support for the American Eugenics Society, as well as for discriminatory practices within his company and associated institutions. In his final years, suffering from a debilitating spinal disorder and severe pain, Eastman died by suicide on March 14, 1932, leaving a note that read, "To my friends, my work is done - Why wait?"

2. Early life and background

George Eastman's formative years were marked by his family's financial struggles and his early exposure to the burgeoning industrial landscape of Rochester, New York, which shaped his self-reliant and innovative spirit.

2.1. Birth and family

George Eastman was born on July 12, 1854, in Waterville, New York, as the youngest of three children to George Washington Eastman and Maria Eastman (née Kilbourn). His parents had purchased a 10 acre (10 acre) farm in 1849 where he was born. He had two older sisters, Ellen Maria and Katie. The family faced financial difficulties, particularly after his father's health declined.

2.2. Childhood and education

Eastman's father had established the Eastman Commercial College in Rochester, New York, in the early 1840s. Rochester was rapidly industrializing at the time, becoming one of the first "boomtowns" in the United States. In 1860, as his father's health deteriorated, the family left their farm and moved to Rochester. George Washington Eastman died of a brain disorder on April 27, 1862, when George was seven years old. To support the family and afford George's schooling, his mother took in boarders.

Eastman was largely self-educated, though he attended a private school in Rochester after the age of eight. His second sister, Katie, contracted polio when young and died in late 1870, when George was 15 or 16 years old. This tragedy prompted the young George to leave school early and begin working to help support his family. As his photography business began to succeed, he vowed to repay his mother for the hardships she endured in raising him. His mother, Maria, passed away in 1907, a loss that deeply affected George. He later stated, "When my mother died I cried all day. I could not have stopped to save my life." Despite his mother's reluctance to accept his gifts during her lifetime, Eastman continued to honor her after her death, dedicating the Kilbourn Theater, a chamber-music hall within the Eastman Theatre, to her memory. He also maintained a rose bush at the Eastman House that was a cutting from her childhood home.

2.3. Early career

Eastman's professional journey began at a young age. He left high school at 14 and started working as an office clerk. He initially earned 3 USD per week at an insurance company before securing a position at the Rochester Savings Bank with an annual salary of 800 USD. It was during his time as a bank clerk in the 1870s that Eastman developed a keen interest in photography.

In 1874, he became fascinated with the process, which at the time involved coating glass plates with a light-sensitive emulsion just before exposure, a cumbersome and difficult method. He took lessons from local photographers George Monroe and George Selden. After three years of dedicated experimentation, he developed a machine for coating dry plates in 1879, a significant improvement over the wet plate process. He secured patents for his dry plates in both the United Kingdom and the United States, marking the beginning of his venture into the photography business in 1880.

3. Career and innovation

George Eastman's career was defined by his entrepreneurial vision and groundbreaking inventions that revolutionized photography and laid the foundation for the modern film industry.

3.1. Interest in photography and early experiments

Eastman's initial foray into photography was driven by a desire to simplify the complex and messy processes of the time. His early work focused on developing dry plates, which eliminated the need for photographers to prepare plates immediately before use. In 1879, he developed a machine to efficiently coat these dry plates, a crucial step toward mass production. Concurrently, he began experimenting with the idea of a flexible film roll that could replace fragile glass plates entirely. In 1884, he patented a process for changing the photographic base from glass to emulsion-coated roll paper, further advancing his vision for a more convenient photographic medium.

3.2. Founding of Eastman Kodak

In 1881, Eastman partnered with Henry A. Strong to establish the Eastman Dry Plate Company. Strong served as the company's president, while Eastman, as treasurer, managed most of the executive functions. The company's initial focus was on selling dry plates.

Eastman's relentless pursuit of innovation led to the development of a practical roll film. In 1885, he received a patent for this flexible film roll, and he then concentrated on creating a camera specifically designed to use it. On September 4, 1888, he patented and released the revolutionary Kodak camera. The name "Kodak" was a word Eastman himself created, chosen for its distinctiveness and ease of pronunciation in any language.

The first Kodak camera came pre-loaded with enough roll film for 100 exposures. Once all exposures were made, the photographer would mail the entire camera back to the Eastman company in Rochester, along with 10 USD. The company would then process the film, make prints of each exposure, load a new roll of film into the camera, and return the camera and prints to the photographer. This innovative service was encapsulated in the iconic slogan, "You press the button, we do the rest." This separation of photo-taking from the laborious development process was a novel concept that made photography far more accessible to amateurs, leading to immediate public popularity. By August 1888, Eastman was struggling to meet the overwhelming demand, and he and his team quickly began developing several other camera models.

The rapidly expanding Eastman Dry Plate Company was reorganized as the Eastman Company in 1889 and then officially incorporated as Eastman Kodak in 1892. The company became known for its distinctive yellow branding on film rolls and packaging, leading some to affectionately call Eastman "Mr. Yellow Coat Kodak."

3.3. Growth of the film industry and Kodak's dominance

Eastman shrewdly recognized that the primary source of revenue would come from the continuous sale of film rolls rather than just camera sales. He strategically focused on film production, providing high-quality, affordable film to every camera manufacturer. This approach effectively turned competitors into de facto business partners, solidifying Kodak's position in the market. In 1889, he patented the processes for the first nitrocellulose film in collaboration with chemist Henry Reichenbach.

Kodak's rapid growth was fueled by its aggressive pursuit of a near-monopoly through strategic patents and acquisitions. By 1896, Kodak had become the leading international supplier of film stock. By 1915, it was the largest employer in Rochester, boasting over 8,000 employees and annual earnings of 15.70 M USD. By 1934, shortly after Eastman's death, Kodak's workforce had expanded to 23,000.

The burgeoning motion picture industry became one of the largest markets for Kodak's film. When Thomas Edison and other film producers formed the Motion Picture Patents Company in 1908, Eastman negotiated for Kodak to be the sole supplier of film to the entire industry. However, these monopolistic actions attracted the attention of the federal government, leading to an antitrust investigation into Kodak in 1911. The investigation focused on exclusive contracts, acquisitions of competitors, and price-fixing. This resulted in a lawsuit against Kodak in 1913, culminating in a final judgment in 1921 that ordered Kodak to cease price-fixing and divest many of its interests.

Eastman also faced numerous patent infringement lawsuits throughout his career. One notable case involved Henry Reichenbach, who sued after being fired in 1892. The most significant legal challenge came from rival film producer Ansco, which acquired a patent for nitrocellulose film filed by inventor Hannibal Goodwin in 1887 (prior to Eastman's patent) but not granted until 1898. Kodak ultimately lost this decade-long lawsuit, incurring costs of 5.00 M USD.

3.4. Major innovations

Kodak's growth continued into the 20th century through a stream of innovations in film and cameras. A notable product was the Brownie camera, launched in 1900 for 1 USD, which was specifically marketed to children and played a significant role in popularizing photography among the masses.

Eastman's interest extended to color photography, beginning in 1904. He funded extensive experiments in color film production for the next decade. The initial result, created by John Capstaff, was a two-color process named Kodachrome. Later, in 1935, Kodak released the more famous second Kodachrome, which was the first marketed integral tripack film.

During World War I, Eastman established a photographic school in Rochester to train pilots for aerial reconnaissance, demonstrating photography's strategic importance.

Eastman was also progressive in his approach to labor relations. In an era of growing trade union activities, he sought to preempt worker demands by implementing various benefit programs. These included a welfare fund to provide workmen's compensation in 1910 and a profit-sharing program for all employees in 1912.

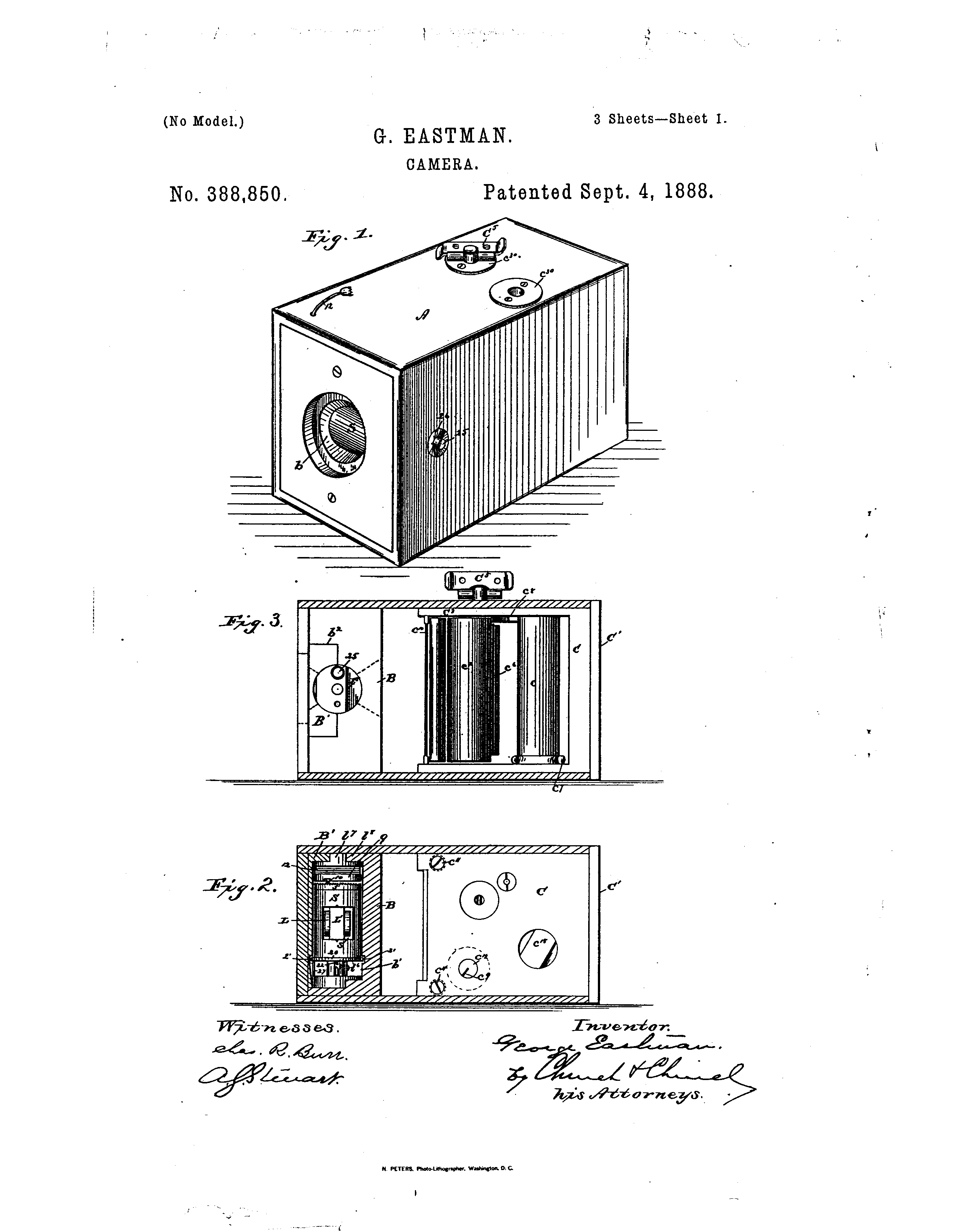

3.5. Key patents

George Eastman's contributions to photography are underscored by his numerous patents, which protected his groundbreaking inventions in film, cameras, and manufacturing processes. His significant patents include:

- United States Patent 226503: "Method and Apparatus for Coating Plates", filed September 1879, issued April 1880.

- United States Patent 306470: "Photographic Film", filed May 10, 1884, issued October 14, 1884.

- United States Patent 306594: "Photographic Film", filed March 7, 1884, issued October 14, 1884.

- United States Patent 317049: (with William H. Walker) "Roll Holder for Photographic Films", filed August 1884, issued May 1885.

- United States Patent 388850: "Camera", filed March 1888, issued September 1888.

Eastman also licensed, and later purchased, United States Patent 248179: "Photographic Apparatus" (a roll film holder), filed June 21, 1881, and issued October 11, 1881, to David H. Houston.

5. Personal life

George Eastman's personal life was characterized by deep family bonds, a range of personal interests, and a lifelong dedication to his work and philanthropic endeavors, which he pursued as a lifelong bachelor.

5.1. Family and relationships

Eastman never married. He maintained a close relationship with his mother, Maria, and his sister, Ellen Maria, and her family. He also developed a long-standing platonic relationship with Josephine Dickman, a trained singer and the wife of his business associate, George Dickman. This bond deepened significantly after his mother's death in 1907.

5.2. Hobbies and interests

Beyond his professional pursuits, Eastman was an avid traveler, enjoying journeys to various parts of the world. He had a strong appreciation for music, frequently attending social gatherings and demonstrating a passion for playing the piano.

5.3. Single life

Eastman remained a bachelor throughout his life. His dedication to his scientific research, business ventures, and extensive philanthropic activities consumed much of his time and energy, potentially contributing to his lifelong commitment to a single life.

6. Later years and death

George Eastman's final years were marked by a transition from daily management, a decline in health, and a profound decision that ended his life.

6.1. Retirement from management

In 1925, George Eastman formally stepped down from the daily operational management of Kodak, officially retiring as president. However, he remained deeply involved with the company in an executive capacity, serving as chairman of the board until his death. During this period, he particularly focused on contributing to the development of the company's research and development department. He had also established the Eastman Savings and Loan in 1920 to provide financial services to Kodak employees, an institution later rechartered as ESL Federal Credit Union. Eastman was also a presidential elector in 1900 and 1916.

6.2. Illness and suicide

In his final two years, Eastman suffered from intense pain caused by a debilitating disorder affecting his spine. He found it increasingly difficult to stand, and his walk became a slow shuffle. Modern medical understanding suggests he may have suffered from a form of degenerative disease such, as disc herniations causing painful nerve root compressions, or a type of lumbar spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal due to calcification in the vertebrae. His mother had also used a wheelchair during the final two years of her life, though her documented health history only mentions successful surgery for uterine cancer, not a spinal condition. Witnessing his mother's suffering and experiencing his own escalating pain and physical decline led Eastman to severe depression.

On March 14, 1932, at his home, George Eastman died by suicide with a single gunshot through the heart. He left a concise and poignant suicide note that read, "To my friends, my work is done - Why wait? GE." Raymond Granger, an insurance salesman visiting to collect payments from staff members, was among those who arrived at the scene to find the workforce in shock. Some chroniclers suggest that Eastman's fear of senility or other debilitating diseases of old age was a contributing factor to his decision.

6.3. Funeral and inheritance

Eastman's funeral was held at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Rochester. His coffin was carried out to Charles Gounod's "Marche Romaine." He was buried on the grounds of the company he founded, at what is now known as Eastman Business Park. The Security Trust Company of Rochester served as the executor of his estate. In a final act of philanthropy, Eastman bequeathed his entire estate to the University of Rochester.

7. Legacy and evaluation

George Eastman's legacy is immense, encompassing his revolutionary impact on photography, his industrial leadership, and his extensive philanthropic contributions, though his life and work also draw critical scrutiny.

7.1. Public image and biography

Throughout his life, Eastman disdained public notoriety and meticulously sought to control his public image. He was reluctant to share information in interviews, and on multiple occasions, both Eastman and Kodak actively blocked biographers from gaining full access to his records. It was not until 1996 that a definitive biography was finally published, offering a more complete picture of his life.

7.2. Honors and commemorations

Eastman has been widely honored for his contributions. He is the only individual to be represented by two stars in the Film category on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, one on Hollywood Boulevard and another on Vine Street, both recognizing his development of bromide paper, which became an industry standard.

The University of Rochester has named the Eastman Quadrangle on its River Campus in his honor. The Rochester Institute of Technology also has a building dedicated to him, acknowledging his substantial support and donations. At MIT, a plaque of Eastman is installed on one of the buildings he funded, and students traditionally rub the nose of Eastman's image on the plaque for good luck.

Eastman's former mansion at 900 East Avenue in Rochester, where he entertained friends and hosted private music concerts, was adapted and reopened in 1949 as the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film. It has since been designated a National Historic Landmark and is now known as the George Eastman Museum. His boyhood home was also preserved, relocated, and is now displayed at the Genesee Country Village and Museum.

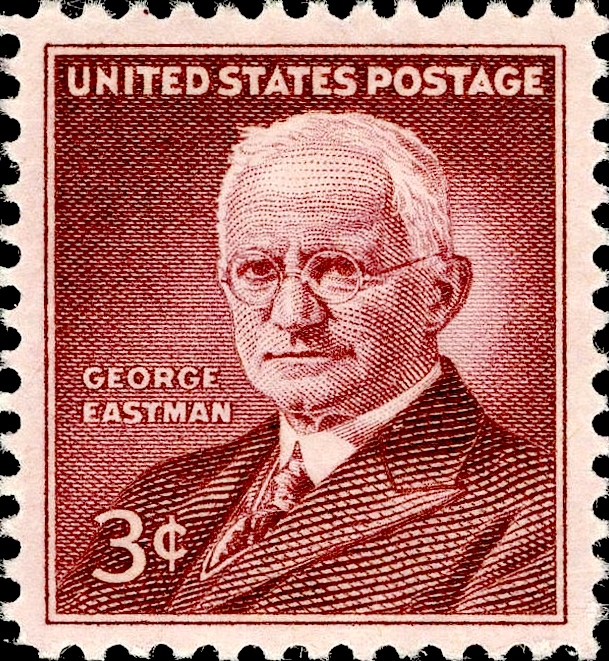

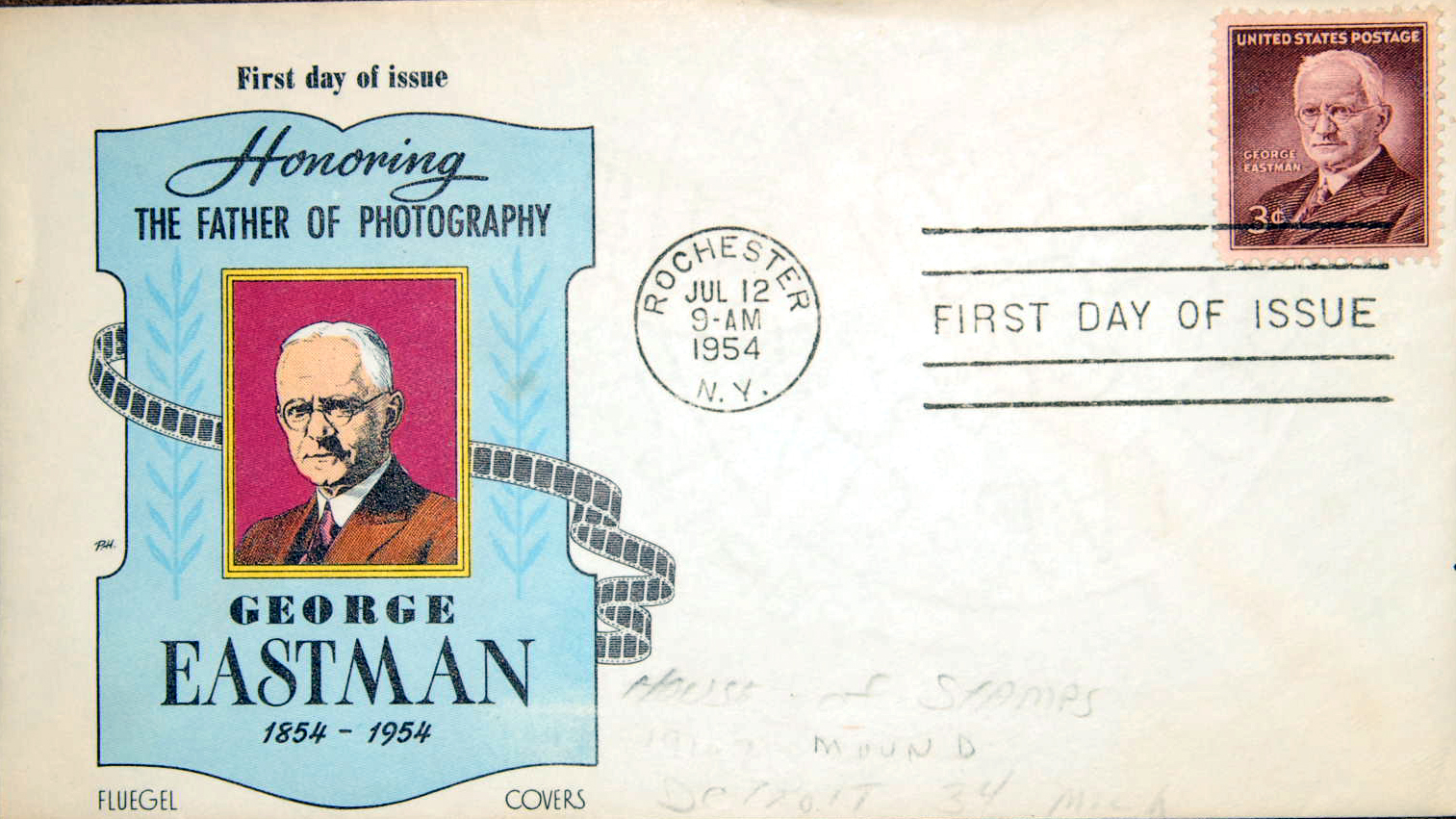

In 1930, Eastman was awarded the American Institute of Chemists Gold Medal. A monument dedicated to George Eastman was unveiled at Kodak Park (now Eastman Business Park) in 1934. On July 12, 1954, the U.S. Post Office issued a three-cent commemorative stamp marking the 100th anniversary of his birth, with its first issue in Rochester. Also in 1954, the University of Rochester erected a meridian marker near the center of the Eastman Quadrangle, funded by a gift from Eastman's former associate and University alumnus Charles F. Hutchison. A statue of Eastman was erected approximately 60 ft north-northeast of this meridian marker on the Eastman Quadrangle in the fall of 2009. In 1968, Eastman was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum. The auditorium at the Dave C. Swalm School of Chemical Engineering at Mississippi State University is also named for him.

7.3. Impact on photography and film industry

Eastman's most profound impact was on the accessibility and widespread adoption of photography. His invention of flexible roll film and the user-friendly Kodak camera, coupled with his "You press the button, we do the rest" service, removed the technical barriers that had previously limited photography to a select few. This made amateur photography a mainstream activity for the first time. He astutely recognized that the sale of film, rather than cameras, would be the primary revenue driver, a strategy that cemented Kodak's dominance.

Furthermore, his innovations in film technology, particularly the development of transparent cellulose film in 1889, provided the essential foundation for the burgeoning motion picture industry. His work directly influenced early pioneers like Edward Muybridge, Louis Le Prince, Léon Bouly, Thomas Edison, the Lumière brothers, and Georges Méliès, enabling the creation and popularization of cinema. Eastman's continuous investment in research and development, along with strategic business practices, ensured Kodak remained at the forefront of photographic innovation for decades, introducing products like the Brownie camera and advancements in color photography such as Kodachrome.

7.5. Criticisms and controversies

Despite his immense contributions and philanthropic endeavors, George Eastman's legacy is not without criticism, particularly concerning his views on race and his support for controversial social movements. Marion Gleason, a close confidante of Eastman, described his views on African Americans as "typical of his time - paternalistic, but strictly against social fraternization."

While he made exceptionally generous donations to historically black institutions like the Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Institute, becoming their largest donor in his era, he simultaneously upheld and reinforced the de facto segregation prevalent in Rochester. During Eastman's lifetime, Kodak hired virtually no black employees; a 1939 commission of the New York State Legislature on living conditions of African Americans found that Kodak had only a single black employee. Furthermore, the Eastman Dental Dispensary reportedly rejected black applicants, and the Eastman Theater restricted black patrons to its balcony. Eastman also rejected several requests to meet with NAACP representatives, including a direct appeal from president Walter Francis White in 1929.

From 1925 until his death, Eastman annually donated 10.00 K USD (increasing to 15.00 K USD in 1932) to the American Eugenics Society. Eugenics was a popular cause among many members of the upper class at the time, fueled by concerns about immigration and "race mixing." This financial support for a movement that advocated for selective breeding to "improve" the human race remains a controversial aspect of his legacy.

8. Representation in other media

George Eastman's life and groundbreaking work have been featured in various media.

- The PBS program American Experience produced an episode titled The Wizard of Photography: The story of George Eastman and how he transformed photography, which first aired on May 22, 2000.

- Several short documentary films about his life have been produced and are regularly screened at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester.