1. Life

Ernest Orlando Lawrence's personal journey and academic development were marked by a blend of intuitive scientific genius and a practical, hands-on approach that would define his career.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was born on August 8, 1901, in Canton, South Dakota. His parents, Carl Gustavus (1871-1954) and Gunda Regina (née Jacobson) Lawrence (1874-1959), were both descendants of Norwegian immigrants. They had met while teaching at the high school in Canton, where his father also served as the superintendent of schools. Lawrence had a younger brother, John H. Lawrence, who would later become a physician and a pioneer in the field of nuclear medicine. Growing up, his closest friend was Merle Tuve, who also became a highly accomplished physicist and developed the proximity fuse.

Lawrence attended public schools in Canton and Pierre. He initially enrolled at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, with aspirations of studying medicine. However, after a year, he transferred to the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, where he continued his medical studies. His path shifted under the influence of Lewis Akeley, a professor in the electrical engineering department, leading Lawrence to pursue physics and chemistry. He completed his bachelor's degree in chemistry with excellent grades in 1922. He then earned his Master of Arts (M.A.) degree in physics from the University of Minnesota in 1923, under the supervision of William Francis Gray Swann. For his master's thesis, Lawrence constructed an experimental apparatus that rotated an ellipsoid through a magnetic field.

Lawrence followed Swann first to the University of Chicago in 1923 and then to Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1924. He completed his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree in physics from Yale in 1925 as a National Research Fellow, writing his doctoral thesis on the photoelectric effect in potassium vapor. He was elected a member of Sigma Xi and, on Swann's recommendation, received a National Research Council fellowship. Unlike the common practice of the time, which involved traveling to Europe for further research, Lawrence chose to remain at Yale University with Swann as a researcher. With Jesse Beams from the University of Virginia, Lawrence continued his research on the photoelectric effect. They demonstrated that photoelectrons appeared within 2 x 10-9 seconds of photons striking the photoelectric surface, a measurement close to the limit of the technology at the time. They also observed that rapidly switching the light source on and off to reduce the emission time broadened the spectrum of emitted energy, which was consistent with Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

1.2. Early Career and Research

In 1926 and 1927, Lawrence received offers for assistant professorships from the University of Washington in Seattle and the University of California at a salary of 3.50 K USD per annum. Yale promptly matched the offer of an assistant professorship, but at a slightly lower salary of 3.00 K USD. Lawrence chose to remain at the more prestigious Yale. However, because he had never been an instructor, his appointment was met with some resentment from fellow faculty members, and for many, it did not fully compensate for his South Dakota immigrant background.

In 1928, Lawrence was hired as an associate professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Two years later, he became the university's youngest full professor. His arrival at Berkeley marked the beginning of his ascent as a prominent physicist, where he was soon dubbed "the key to nuclear energy." In 1934, building on the published work of Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie on artificial radioactivity, Lawrence discovered the nitrogen-13 isotope by firing high-energy protons into a carbon-13 element in his laboratory. He and his team, including Martin Kamen and Samuel Ruben, accidentally discovered the carbon-14 isotope by bombarding graphite with high-energy protons.

Robert Gordon Sproul, who became university president the day after Lawrence became a full professor, was a member of the Bohemian Club. In 1932, Sproul sponsored Lawrence's membership in the club. Through this connection, Lawrence met influential figures such as William Henry Crocker, Edwin Pauley, and John Francis Neylan, who helped him secure funding for his ambitious nuclear particle investigations. The great hope for medical applications arising from the development of particle physics was a significant factor in the early funding Lawrence was able to obtain for his research.

While at Yale, Lawrence met Mary Kimberly (Molly) Blumer, the eldest of four daughters of George Blumer, the dean of the Yale School of Medicine. They first met in 1926 and became engaged in 1931, marrying on May 14, 1932, at Trinity Church on the Green in New Haven, Connecticut. They had six children: Eric, Margaret, Mary, Robert, Barbara, and Susan. Lawrence named his son Robert after Robert Oppenheimer, his closest friend in Berkeley. In 1941, Molly's sister Elsie married Edwin McMillan, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1951 with Glenn T. Seaborg.

2. Major Activities and Achievements

Lawrence's career was defined by his groundbreaking inventions, his critical contributions during wartime, and his transformative leadership in post-war science, particularly his advocacy for "Big Science."

2.1. Invention and Development of the Cyclotron

The invention that brought Lawrence international fame began as a simple sketch on a paper napkin, evolving into a revolutionary device that transformed nuclear physics.

2.1.1. Conception and Initial Design

In 1929, while in the library, Lawrence was intrigued by a diagram in a journal article by Rolf Widerøe. The diagram depicted a device that produced high-energy particles through a succession of small "pushes." However, the device was laid out in a straight line, requiring increasingly longer electrodes to achieve higher energies. At the time, physicists were just beginning to explore the atomic nucleus. In 1919, Ernest Rutherford had succeeded in knocking protons out of nitrogen nuclei by firing alpha particles into them. Yet, to truly break apart or disintegrate nuclei, which possess a positive charge that repels other positively charged nuclei and are tightly bound by forces, much higher energies-on the order of millions of volts-were required.

Lawrence recognized that a linear particle accelerator would quickly become too long and unwieldy for a university laboratory. He conceived a way to make the accelerator more compact by setting a circular accelerating chamber between the poles of an electromagnet. The magnetic field would hold the charged protons in a spiral path as they were accelerated between just two semicircular electrodes, connected to an alternating potential. After numerous turns, the protons would impact the target as a beam of high-energy particles. Lawrence excitedly informed his colleagues that he had discovered a method for obtaining particles of very high energy without the need for extremely high voltage.

He initially collaborated with Niels Edlefsen on this idea. Their first cyclotron was a small, 4 in diameter device constructed from brass, wire, and sealing wax, small enough to be held in one hand, and costing approximately 25 USD.

2.1.2. Technical Development and Expansion

After Edlefsen departed for an assistant professorship in September 1930, Lawrence sought capable graduate students to advance his idea. He brought in David H. Sloan and M. Stanley Livingston. Sloan worked on developing Widerøe's linear accelerator, successfully accelerating ions to 1 MeV by May 1931. Livingston, facing a greater technical challenge with the cyclotron, achieved significant success. On January 2, 1931, by applying 1,800 V to his 11-inch cyclotron, he produced 80,000-electron volt protons. A week later, he reached 1.22 MeV with 3,000 V, which was more than sufficient for his PhD thesis on its construction.

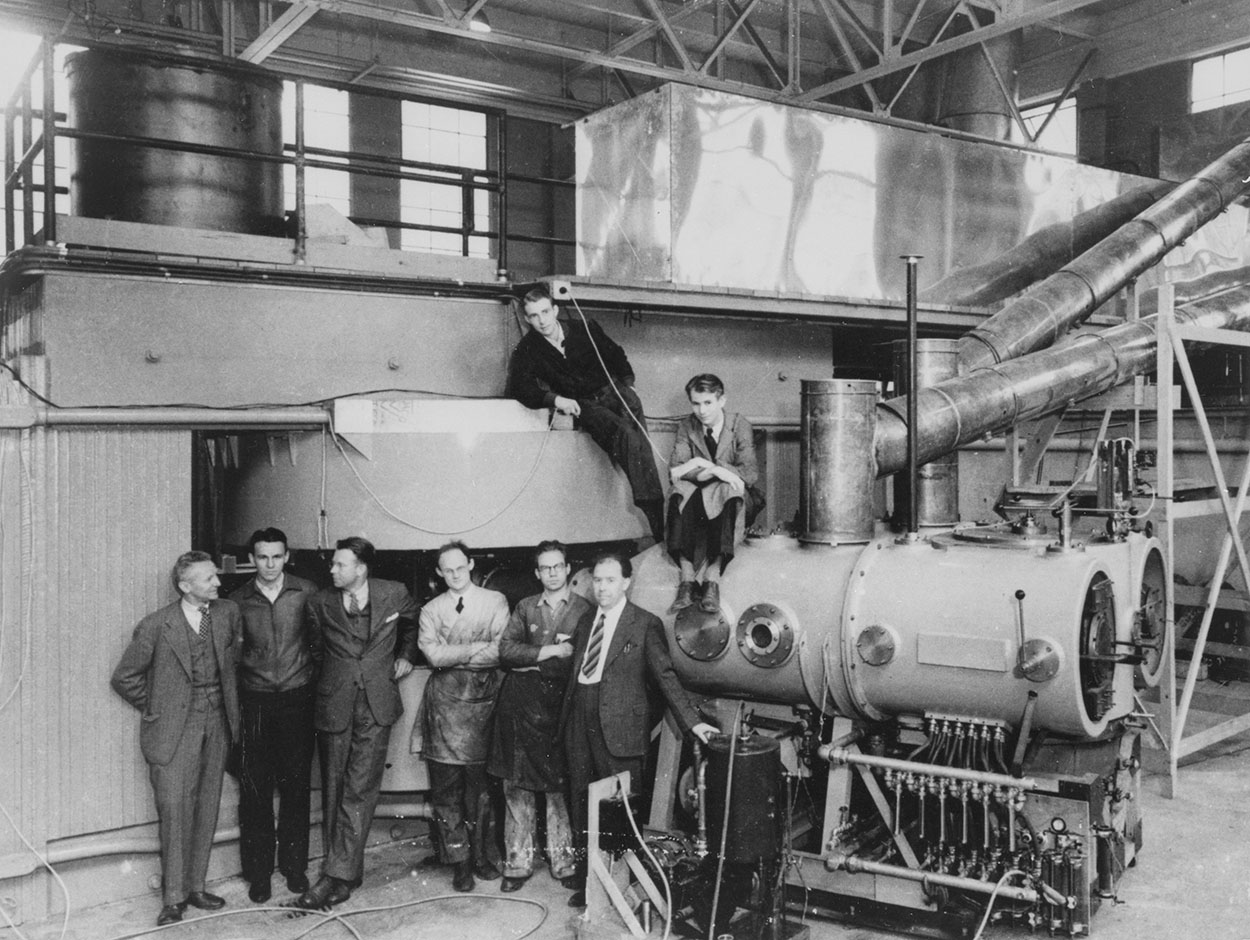

This early success established a recurring pattern in Lawrence's work: as soon as a prototype showed promise, he would immediately begin planning a new, larger, and more expensive machine. In early 1932, Lawrence and Livingston designed a 27 in cyclotron. While the magnet for the 11-inch cyclotron weighed 2 t, Lawrence located a massive 80 t magnet rusting in a junkyard in Palo Alto. This magnet had originally been built during World War I to power a transatlantic radio link, and it was repurposed for the 27-inch cyclotron.

Lawrence received a patent for the cyclotron in 1934, which he assigned to the Research Corporation, a private foundation that provided significant funding for much of his early work. Despite the cyclotron's growing power, major scientific discoveries initially eluded Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory, primarily because the team focused more on the development and refinement of the cyclotron itself rather than its immediate scientific applications. Nevertheless, through his increasingly larger machines, Lawrence provided crucial equipment for experiments in high-energy physics. Around this device, he built what became the world's foremost laboratory for the new field of nuclear physics research in the 1930s.

In February 1936, Harvard University's president, James B. Conant, made attractive offers to both Lawrence and Robert Oppenheimer. In response, the University of California's president, Robert Gordon Sproul, improved the conditions at Berkeley. On July 1, 1936, the Radiation Laboratory became an official department of the University of California, with Lawrence formally appointed as its director and a full-time assistant director. The university also committed to providing 20.00 K USD annually for its research activities. Lawrence adopted a distinct business model for his laboratory: he staffed it with graduate students, junior faculty from the physics department, recent PhDs willing to work for minimal pay, and fellowship holders or wealthy guests who could serve without compensation. This approach fostered a dynamic and productive research environment.

2.1.3. Scientific and Societal Reception

Using the new 27-inch cyclotron, the Berkeley team observed that every element they bombarded with recently discovered deuterium emitted energy within the same range. They postulated the existence of a new, unknown particle as a possible source of limitless energy. William Laurence of The New York Times hailed Lawrence as "a new miracle worker of science."

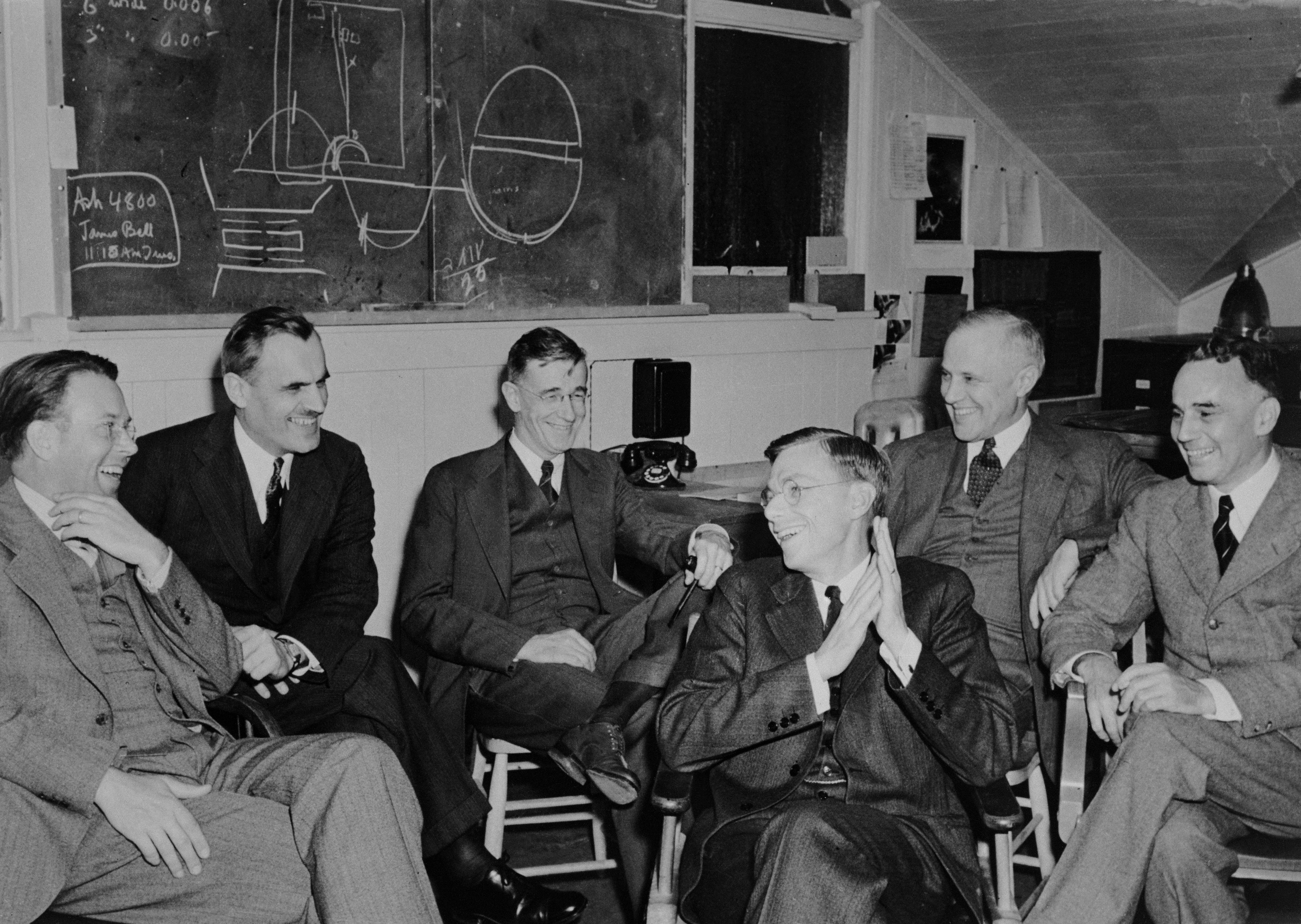

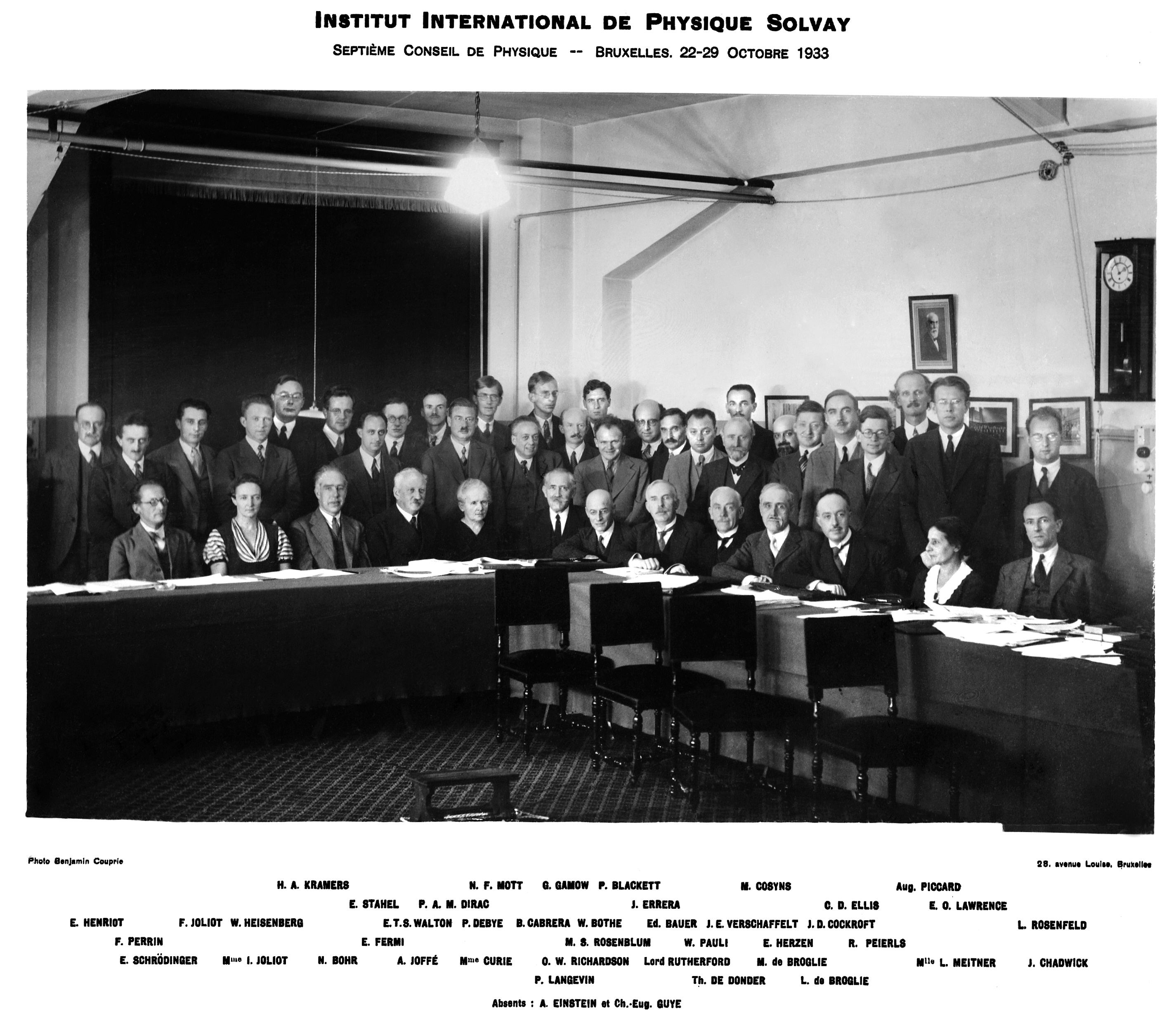

At the invitation of John Cockcroft, Lawrence attended the 1933 Solvay Conference in Belgium, a prestigious gathering of the world's leading physicists, predominantly from Europe. Lawrence was asked to present on the cyclotron. However, his claims of limitless energy were met with skepticism, particularly from James Chadwick of the Cavendish Laboratory, who had discovered the neutron in 1932. Chadwick, in an accent that Lawrence perceived as condescending, suggested that the observations were due to contamination of their apparatus.

Upon his return to Berkeley, Lawrence mobilized his team to meticulously re-examine their results to gather sufficient evidence to convince Chadwick. Meanwhile, at the Cavendish Laboratory, Rutherford and Mark Oliphant discovered that deuterium fuses to form helium-3, which explained the effect the cyclotroneers had observed. Chadwick's assessment was correct: Lawrence's team had indeed been observing contamination, and in doing so, they had overlooked another significant discovery-that of nuclear fusion. Lawrence's response was to push forward with the creation of even larger cyclotrons. The 27-inch cyclotron was succeeded by a 37-inch cyclotron in June 1937, which was then replaced by a 60-inch cyclotron in May 1939. The 60-inch cyclotron was used to bombard iron and produced its first radioactive isotopes in June of that year.

Lawrence was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in November 1939 "for the invention and development of the cyclotron and for results obtained with it, especially with regard to artificial radioactive elements." He was the first Nobel Laureate from Berkeley, the first from South Dakota, and the first to be honored while at a state-supported university. Due to World War II, the Nobel award ceremony was held on February 29, 1940, in Berkeley, California, at the auditorium of Wheeler Hall on the university campus. Lawrence received his medal from Carl E. Wallerstedt, Sweden's Consul General in San Francisco. Robert W. Wood wrote to Lawrence, presciently noting, "As you are laying the foundations for the cataclysmic explosion of uranium... I'm sure old Nobel would approve."

In March 1940, a group of prominent scientists and administrators, including Arthur Compton, Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Karl T. Compton, and Alfred Lee Loomis, traveled to Berkeley to discuss Lawrence's proposal for a 184 in cyclotron, which would feature a 4.50 K t magnet and was estimated to cost 2.65 M USD. The Rockefeller Foundation provided 1.15 M USD to initiate the project.

2.2. Scientific Contributions and Discoveries

Through the cyclotron, Lawrence and his team made significant advancements in understanding isotopes and their applications, particularly in medicine.

2.2.1. Isotope and Element Discoveries

Building on the work of others, Lawrence and his team made crucial discoveries of artificial radioactive isotopes and the synthesis of new elements. Following the published research on artificial radioactivity by Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie in 1934, Lawrence discovered the nitrogen-13 isotope by bombarding carbon-13 with high-energy protons. Later, his team, including Martin Kamen and Samuel Ruben, accidentally discovered the carbon-14 isotope by bombarding graphite with high-energy protons.

In December 1940, Glenn T. Seaborg and Emilio Segrè, using the 60 in cyclotron, bombarded uranium-238 with deuterons, producing a new element, neptunium-238. This element then decayed by beta emission to form plutonium-238. Crucially, one of its isotopes, plutonium-239, was found to be capable of nuclear fission, offering another pathway for creating an atomic bomb. The discovery of plutonium was kept secret until the end of World War II due to its potential military applications. Lawrence's laboratory was also instrumental in the discovery of technetium and most of the transuranic elements synthesized up to the 1950s.

2.2.2. Applications in Medicine and Biochemistry

Recognizing the greater ease of securing funding for medical purposes, particularly cancer treatment, compared to pure nuclear physics, Lawrence actively encouraged the use of the cyclotron for medical research. He collaborated with his brother, John H. Lawrence, a physician and pioneer in nuclear medicine, and Israel Lyon Chaikoff from the University of California's physiology department, to explore the therapeutic applications of radioactive isotopes.

Phosphorus-32 was easily produced in the cyclotron, and John H. Lawrence successfully used it to treat a woman afflicted with polycythemia vera, a blood disease. John also conducted tests on mice with leukemia in 1938, finding that radioactive phosphorus concentrated in fast-growing cancer cells. This discovery led to clinical trials on human patients, and a 1948 evaluation of the therapy showed that remissions occurred under certain circumstances. Ernest Lawrence also held high hopes for the medical use of neutrons. The first cancer patient received neutron therapy from the 60 in cyclotron on November 20, 1939. Chaikoff, in turn, conducted trials on the use of radioactive isotopes as radioactive tracers to explore the mechanisms of biochemical reactions.

2.3. World War II and the Manhattan Project

Lawrence's critical involvement in the U.S. war effort, particularly his contributions to the development of nuclear weapons, marked a significant turning point in his career and the history of science.

2.3.1. Radiation Laboratory and Uranium Enrichment

After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, Lawrence became deeply involved in military projects. He assisted in recruiting staff for the MIT Radiation Laboratory, where American physicists developed the cavity magnetron, a technology invented by Mark Oliphant's team in Britain. The new laboratory's name was deliberately copied from Lawrence's laboratory in Berkeley for security reasons. He also participated in recruiting personnel for underwater sound laboratories, which focused on developing techniques for detecting German submarines.

Meanwhile, work continued at Berkeley with the cyclotrons. In December 1940, Glenn T. Seaborg and Emilio Segrè used the 60 in cyclotron to bombard uranium-238 with deuterons, producing a new element, neptunium-238, which subsequently decayed by beta emission to form plutonium-238. One of its isotopes, plutonium-239, was found to be fissile, providing another potential pathway for creating an atomic bomb.

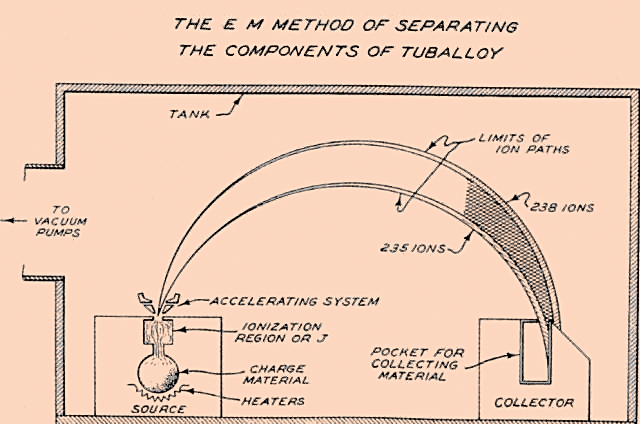

In September 1941, Mark Oliphant met with Lawrence and Oppenheimer at Berkeley, where they showed him the site for the new 184 in cyclotron. Oliphant, in turn, challenged the Americans for not following up on the recommendations of the British MAUD Committee, which advocated for a program to develop an atomic bomb. Lawrence had already been considering the complex problem of separating the fissile isotope uranium-235 from uranium-238, a process known today as uranium enrichment. Separating uranium isotopes was particularly difficult because the two isotopes possess nearly identical chemical properties and could only be gradually separated using their minuscule mass differences. Separating isotopes with a mass spectrometer was a technique Oliphant had pioneered with lithium in 1934.

Lawrence began converting his old 37-inch cyclotron into a giant mass spectrometer for this purpose. On his recommendation, the director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves Jr., appointed Oppenheimer as head of its Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. While Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory developed the electromagnetic uranium enrichment process, the Los Alamos Laboratory was responsible for designing and constructing the atomic bombs. Both laboratories were managed by the University of California.

The electromagnetic isotope separation process utilized devices known as calutrons, a hybrid of two standard laboratory instruments: the mass spectrometer and the cyclotron. The name "calutron" was derived from "California university cyclotrons." In November 1943, Lawrence's team at Berkeley was significantly bolstered by the arrival of 29 British scientists, including Oliphant. In the electromagnetic process, a magnetic field deflected charged particles according to their mass, allowing for separation. The process was neither scientifically elegant nor industrially efficient; compared with a gaseous diffusion plant or a nuclear reactor, an electromagnetic separation plant consumed more scarce materials, required more manpower to operate, and was more expensive to build. Nevertheless, the process was approved because it was based on proven technology, thus presenting less risk, and could be built in stages, rapidly scaling up to industrial capacity.

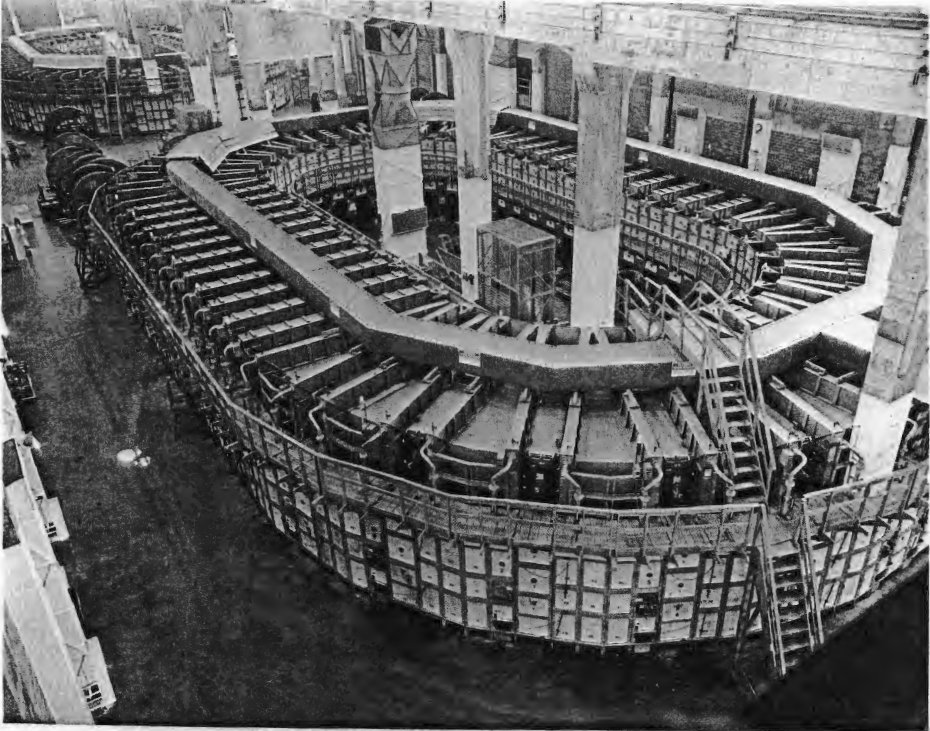

2.3.2. Nuclear Material Production at Oak Ridge

Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which came to be known as Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster. The calutrons, which required 14.70 K t of silver for their coils, were manufactured by Allis-Chalmers in Milwaukee and shipped to Oak Ridge. The initial design called for five first-stage processing units, known as Alpha racetracks, and two units for final processing, known as Beta racetracks. In September 1943, Groves authorized the construction of four additional racetracks, designated as Alpha II.

When the plant commenced test operations on schedule in October 1943, a significant problem arose: the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment due to the immense power of the magnets and had to be more securely fastened. A more serious issue emerged when the magnetic coils began to short out. In December, Groves ordered a magnet to be opened, revealing handfuls of rust inside. Groves then mandated that the racetracks be dismantled and the magnets sent back to the factory for thorough cleaning. A pickling plant was established on-site to clean the pipes and fittings, addressing the contamination issue.

Tennessee Eastman was hired to manage the Y-12 plant. Initially, Y-12 enriched the uranium-235 content to between 13% and 15%, shipping the first few hundred grams of it to Los Alamos Laboratory in March 1944. The process was highly inefficient, with only 1 part in 5,825 of the uranium feed emerging as the final product, the rest being splattered over equipment. Strenuous recovery efforts helped raise production to 10% of the uranium-235 feed by January 1945. In February, the Alpha racetracks began receiving slightly enriched (1.4%) feed from the new S-50 thermal diffusion plant. The following month, they received enhanced (5%) feed from the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant. By April 1945, K-25 was producing uranium sufficiently enriched to feed directly into the Beta tracks.

On July 16, 1945, Lawrence observed the Trinity nuclear test of the first atomic bomb with Chadwick and Charles A. Thomas. Few were more excited by its success than Lawrence. The question of how to use the now functional weapon on Japan became a contentious issue among the scientists. While Oppenheimer favored no demonstration of the new weapon's power to Japanese leaders, Lawrence strongly believed that a demonstration would be a wise course of action. When a uranium bomb was used without warning in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Lawrence felt great pride in his accomplishment.

Lawrence had hoped that the Manhattan Project would continue to develop improved calutrons and construct Alpha III racetracks, but these were ultimately judged to be uneconomical. The Alpha tracks were shut down in September 1945. Although performing better than ever, they could not compete with the efficiency of K-25 and the new K-27, which began operation in January 1946. In December 1946, the Y-12 plant was closed, reducing the Tennessee Eastman payroll from 8,600 to 1,500 employees and saving 2.00 M USD per month. Staff numbers at the Radiation Laboratory also declined significantly, falling from 1,086 in May 1945 to 424 by the end of the year.

2.4. Post-War Activities and "Big Science"

After World War II, Lawrence transitioned to advocating for and shaping large-scale, government-funded scientific research programs, a concept he termed "Big Science."

2.4.1. Advocacy for Big Science

After the war, Lawrence campaigned extensively for government sponsorship of large scientific programs. He was a forceful advocate of "Big Science," emphasizing the need for massive facilities, significant funding, and collaborative research teams. In 1946, he requested over 2.00 M USD from the Manhattan Project for research at the Radiation Laboratory. General Groves approved the funding but cut several programs, including Seaborg's proposal for a "hot" radiation laboratory in densely populated Berkeley and John Lawrence's for the production of medical isotopes, as this need could now be better met by nuclear reactors. One obstacle was the University of California, which was eager to divest itself of its wartime military obligations. However, Lawrence and Groves successfully persuaded President Sproul to accept a contract extension. By 1946, the Manhattan Project was spending 7 USD on physics at the University of California for every dollar spent by the university itself, illustrating the significant shift towards government-funded research.

Lawrence's approach to physics was notably intuitive and practical. He appeared to have an almost aversion to abstract mathematical thought, preferring to focus on the "physics of the problem" rather than intricate differential equations. Despite this, he retained a complete mastery of the mathematics of classical electricity and magnetism.

2.4.2. Development of New Accelerators and Laboratory Founding

The 184 in cyclotron, which had been planned before the war, was completed with wartime funding from the Manhattan Project. It incorporated new ideas by Edwin McMillan and was completed as a synchrocyclotron, commencing operation on November 13, 1946. For the first time since 1935, Lawrence actively participated in the experiments, working with Eugene Gardner in an unsuccessful attempt to create recently discovered pi mesons with the synchrotron. César Lattes later used the apparatus they had created to find negative pi mesons in 1948.

Responsibility for the national laboratories transitioned to the newly created Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) on January 1, 1947. That year, Lawrence requested 15.00 M USD for his projects, which included a new linear accelerator and a new gigaelectronvolt synchrotron that became known as the Bevatron. The University of California's contract to run the Los Alamos Laboratory was set to expire on July 1, 1948, and some board members wished to divest the university of the responsibility for managing a site outside California. After some negotiation, the university agreed to extend the contract for what was now the Los Alamos National Laboratory for four more years and to appoint Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Oppenheimer as its director in October 1945, as a professor. Soon after, Lawrence received all the funds he had requested.

3. Ideology and Philosophy

Lawrence's underlying principles, scientific approach, and political leanings were deeply intertwined, particularly within the tumultuous context of the Cold War.

3.1. Scientific Methodology

Lawrence was known for his highly intuitive and practical approach to physics. He emphasized experimental results over abstract mathematical theory, often preferring a physical explanation of a problem rather than delving into complex differential equations. This hands-on, problem-solving technique allowed him to quickly grasp the core physics of a situation and drive the development of new experimental apparatus. His colleagues noted his remarkable ability to retain a deep understanding of classical electricity and magnetism, even while seemingly avoiding intricate mathematical details.

3.2. Political Views and Cold War Activities

Despite voting for Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lawrence was a Republican. He strongly disapproved of Oppenheimer's pre-war efforts to unionize the Radiation Laboratory workers, which Lawrence considered "leftwandering activities." Lawrence viewed political activity as a waste of time better spent on scientific research and preferred that it be kept out of the Radiation Laboratory.

In the charged Cold War climate of the post-war University of California, Lawrence accepted the actions of the House Un-American Activities Committee as legitimate and did not perceive them as indicative of a systemic problem involving academic freedom or human rights. While he was protective of individuals within his laboratory, he was even more protective of the laboratory's reputation. He was compelled to defend Radiation Laboratory staff members, such as Robert Serber, who were investigated by the university's Personnel Security Board, and in several cases, he provided character references in support of his staff. However, Lawrence barred Robert Oppenheimer's brother, Frank Oppenheimer, from the Radiation Laboratory, which damaged his relationship with Robert. An acrimonious loyalty oath campaign at the University of California also led to the departure of several faculty members. When hearings were held to revoke Robert Oppenheimer's security clearance, Lawrence declined to attend due to illness, but a transcript in which he was critical of Oppenheimer was presented in his absence. These political tensions contributed to ill-feeling and distrust, ultimately undermining the creative and collaborative environment he had built at the laboratory.

Lawrence was alarmed by the Soviet Union's first nuclear test in August 1949. He concluded that the appropriate response was an all-out effort to build a more powerful nuclear weapon: the hydrogen bomb. He proposed using accelerators instead of nuclear reactors to produce the neutrons needed to create the tritium required for the bomb, as well as plutonium, although the latter was more challenging, requiring much higher energies. He initially proposed the construction of Mark I, a prototype 7.00 M USD, 25 MeV linear accelerator, codenamed the Materials Test Accelerator (MTA). He soon spoke of an even larger MTA, known as the Mark II, which could produce tritium or plutonium from depleted uranium-238. Serber and Segrè attempted in vain to explain the technical problems that made it impractical, but Lawrence felt that their concerns were unpatriotic.

Lawrence strongly supported Edward Teller's campaign for a second nuclear weapons laboratory, which Lawrence proposed to locate alongside the MTA Mark I at Livermore, California. Lawrence and Teller had to argue their case not only with the Atomic Energy Commission, which did not want it, and the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which was implacably opposed, but also with proponents who felt that Chicago was a more obvious site for such a facility. The new laboratory at Livermore was finally approved on July 17, 1952, but the Mark II MTA project was canceled. By this time, the Atomic Energy Commission had spent 45.00 M USD on the Mark I, which had commenced operation but was primarily used to produce polonium for the nuclear weapons program. Meanwhile, the Brookhaven National Laboratory's Cosmotron had already generated a 1 GeV beam.

4. Personal Life

Ernest Lawrence's personal life was centered around his family, providing a foundation amidst his intense scientific pursuits. He married Mary Kimberly (Molly) Blumer on May 14, 1932. Molly was the eldest of four daughters of George Blumer, the dean of the Yale School of Medicine. The couple had six children: Eric, Margaret, Mary, Robert, Barbara, and Susan. Notably, Lawrence named his son Robert after his close friend and colleague, Robert Oppenheimer. His family life was also connected to the broader scientific community, as Molly's sister Elsie married Edwin McMillan, who later became a Nobel laureate.

5. Death

In July 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Lawrence to travel to Geneva, Switzerland, to help negotiate a proposed Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union. Lewis Strauss, the Chairman of the AEC, had strongly advocated for Lawrence's inclusion in the delegation, as both men had championed the development of the hydrogen bomb, and Strauss had helped raise funds for Lawrence's cyclotron in 1939. Strauss was keen to have Lawrence as part of the Geneva delegation because Lawrence was known to favor continued nuclear testing.

Despite suffering from a serious flare-up of his chronic ulcerative colitis, Lawrence decided to go. However, he became gravely ill while in Geneva and was rushed back to the hospital at Stanford University. Surgeons performed an ileostomy, removing much of his large intestine, but also discovered other severe health issues, including advanced atherosclerosis in one of his arteries. Ernest Orlando Lawrence died in Palo Alto Hospital on August 27, 1958, nineteen days after his 57th birthday. Molly Lawrence did not wish for a public funeral but agreed to a memorial service at the First Congregational Church in Berkeley, where University of California President Clark Kerr delivered the eulogy.

6. Assessment and Legacy

Ernest Orlando Lawrence's enduring impact on science, technology, and society is multifaceted, marked by both profound advancements and complex ethical considerations.

6.1. Major Awards and Honors

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Lawrence received numerous prestigious scientific awards and honors throughout his career. He was awarded the Elliott Cresson Medal and the Hughes Medal in 1937, the Comstock Prize in Physics in 1938, and the Duddell Medal and Prize in 1940. Further accolades included the Holley Medal in 1942, the Medal for Merit in 1946, the William Procter Prize in 1951, and the Faraday Medal in 1952. In 1957, he received the Enrico Fermi Award from the Atomic Energy Commission.

Lawrence was elected a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1934, and both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society in 1937. He was made an Officer of the Legion d'Honneur in 1948 and was the first recipient of the Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy in 1958. In 1982, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

6.2. Namesakes and Memorials

Almost immediately after Lawrence's death, the Regents of the University of California voted to rename two of the university's nuclear research laboratories in his honor: the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award was established in his memory in 1959. Chemical element number 103, discovered at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 1961, was named lawrencium in his honor. In 1968, the Lawrence Hall of Science, a public science education center, was established in his memory. His papers are preserved in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

6.3. Impact on Science and Society

Lawrence's work had a transformative impact on the nature of scientific research itself. Before him, "little science" was largely conducted by lone individuals working with modest means on a small scale. After him, massive industrial and especially governmental expenditures of manpower and monetary funding made "Big Science," carried out by large-scale research teams, a major segment of the national economy. This shift fundamentally altered the fields of particle physics and nuclear technology, fostering an era of large-scale scientific infrastructure and collaborative research. His contributions also highlight the complex and evolving relationship between scientific research, government funding, and policy, particularly in the context of national security and technological advancement.

6.4. Criticisms and Controversies

Lawrence's legacy is not without its criticisms and controversies, particularly concerning his involvement in nuclear weapons development and his political stances during the Cold War. His enthusiastic support for the Manhattan Project and his pride in the use of the atomic bomb, even without warning, on Hiroshima, stand in stark contrast to the ethical dilemmas faced by many of his scientific contemporaries, including Oppenheimer.

The dual-use nature of his scientific discoveries-their potential for both medical benefit and destructive weaponry-remains a central point of ethical debate. This was poignantly illustrated in the 1980s when his widow, Molly Lawrence, repeatedly petitioned the University of California Board of Regents to remove her husband's name from the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, citing its focus on nuclear weapons. Her requests were denied each time, underscoring the enduring tension between scientific progress and its moral implications.

Furthermore, Lawrence's political activities during the Cold War, including his acceptance of the House Un-American Activities Committee's actions and his stance on loyalty oaths, contributed to a climate of distrust and division within the scientific community. His decision to bar Frank Oppenheimer from the Radiation Laboratory and his critical testimony regarding Robert Oppenheimer's security clearance strained personal relationships and highlighted the pressures faced by scientists during a period of intense ideological conflict. These aspects of his career offer a balanced perspective on the complex consequences, both positive and negative, of his profound scientific contributions.