1. Overview

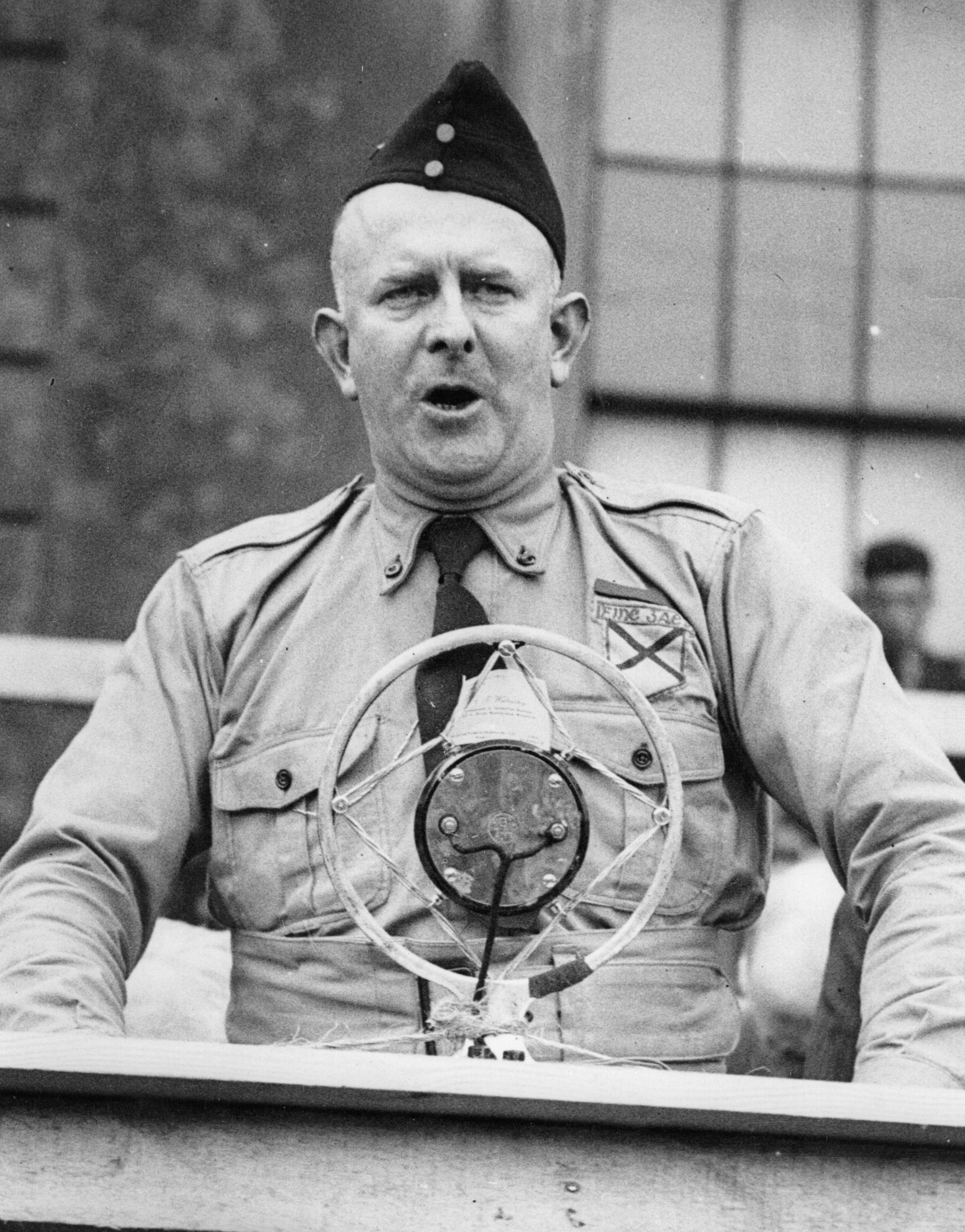

Eoin O'Duffy, born Owen Duffy (Eoin Ó DubhthaighOn O Dhuv-heeIrish), was a prominent Irish revolutionary, soldier, police commissioner, and politician who significantly shaped early 20th-century Irish history. His career spanned leadership roles in the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence and as Chief of Staff of the National Army during the Irish Civil War. Following his military service, he became the second Commissioner of the Garda Síochána, the police force of the new Irish Free State, where he played a crucial role in its establishment and character.

However, O'Duffy's legacy is complex and controversial. In the 1930s, he became deeply attracted to fascism, leading the paramilitary Army Comrades Association, commonly known as the Blueshirts. He briefly served as the first leader of the Fine Gael political party, formed from a merger of conservative groups. His most controversial act was organizing and leading the Irish Brigade to fight for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, motivated by anti-communism and Catholic solidarity. His later life saw continued involvement in pro-Axis circles during World War II, though his influence waned. O'Duffy's career reflects a trajectory from a national hero of the independence movement to a figure widely criticized for his authoritarian and anti-democratic tendencies, leaving a contentious impact on Irish society and political discourse.

2. Early Life and Education

Eoin O'Duffy was born Owen Duffy on January 28, 1890, in Lough Egish, near Castleblayney, County Monaghan. He was the youngest of seven children in an impoverished smallholder family. His father, also named Owen Duffy, inherited a 15 acre (15 acre) farm from his father Peter in 1888. Despite owning land, the family often had to farm conacre land and work on roads to supplement their income.

O'Duffy attended Laggan national school before moving to a school in Laragh. There, he developed a keen interest in the Gaelic Revival and regularly attended night classes hosted by the Gaelic League. His mother, Bridget Fealy, died of cancer when he was 12, a loss that deeply affected him; he wore her ring for the remainder of his life.

3. Early Career

In 1909, O'Duffy sat for the king's scholarship examination for St Patrick's College, Dublin, but a guaranteed place was not secured. Consequently, he pursued a career as a surveyor, applying to become a clerk in the county surveyor's office in Monaghan. He achieved fifth place in the local government board examination in 1912, leading to his appointment. He relocated to Newbliss to commence his new position and later secured a post as an engineer.

4. Military Career and Independence Movement

Eoin O'Duffy's military career was central to his early life, marked by his rapid ascent within the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence and his subsequent leadership role in the National Army during the Irish Civil War.

4.1. Irish War of Independence

In 1917, O'Duffy joined the Irish Volunteers, which later became the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and actively participated in the Irish War of Independence. He quickly rose through the ranks, starting as Section Commander of the Clones Company, then Captain, then Commandant, and finally being appointed Brigadier in 1919. His abilities caught the attention of Michael Collins, who inducted him into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and supported his advancement within the movement. Collins notably described O'Duffy as "the best man in Ulster" in 1920. O'Duffy's extensive involvement in the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) and his detailed knowledge of Monaghan from his surveying job proved invaluable for the IRA's organizational and recruitment efforts.

In 1918, O'Duffy became secretary of Sinn Féin's north Monaghan area council. On September 14, 1918, he and Daniel Hogan were arrested after a GAA match and charged with "illegal assembly," leading to his imprisonment in Belfast Prison until November 19, 1918. Upon his release, O'Duffy focused on organizing his brigade and established an effective intelligence network by cultivating contacts within the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). He was forced to go on the run after an RIC raid on his home in September 1919 but continued to receive his salary from the Monaghan County Council.

On February 15, 1920, O'Duffy, alongside Ernie O'Malley, participated in the first capture of an RIC barracks by the IRA in Ballytrain, Monaghan. This raid significantly boosted local IRA recruitment, undermined RIC morale, and led to the closure of many rural barracks in Monaghan. He was subsequently arrested again and imprisoned in Belfast Prison, where he undertook a hunger strike. Released in June, he then organized Sinn Féin candidates for the 1920 Irish local elections in Monaghan.

O'Duffy's brigade began raiding Protestant homes for arms, which heightened sectarian tensions. While not solely targeting Protestants, these raids were motivated by resentment of Unionist support for the authorities. Some Protestants were outraged, while others reported polite interactions. The raids led to armed Orangemen parading in Unionist areas and retaliatory killings. O'Duffy supported the Belfast Boycott, leading his brigade to harass Protestant stores, burn delivery vans from Belfast, raid trains carrying northern goods, and sabotage rail tracks.

In 1921, O'Duffy adopted more ruthless tactics, intensifying attacks on British forces and executing suspected informers and other opponents of the IRA. Following an incident in February 1921 where a Protestant trader, George Lester, searched two boys suspected of being IRA dispatch carriers, O'Duffy ordered Lester's death. Lester survived, but in retaliation, the B Specials invaded Rosslea on February 23, sacking the Catholic part of the town. A month later, O'Duffy's IRA unit retaliated by burning fourteen houses and killing three Protestants, two of whom were B Specials.

He was appointed Director of the Army in 1921. In May 1921, he was elected as a Sinn Féin Teachta Dála (TD) for the Monaghan constituency to the Second Dáil, and was re-elected in the 1922 Irish general election. In March 1921, he became commander of the IRA's 2nd Northern Division. After the Truce with the British in July 1921, he was sent to Belfast. Following the events of Belfast's Bloody Sunday, he was tasked with liaising with the British to maintain the Truce and defend Catholic areas. During this period, he earned the nickname "Give 'em the lead" after a belligerent speech in South Armagh threatening to use "the lead against them" if Unionists opposed Ireland. He served as Director of Organisation in Ulster and Chief Liaison officer for Ulster when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed. In January 1922, he succeeded Richard Mulcahy as IRA Chief of Staff, becoming the youngest general in Europe until Francisco Franco was promoted to that rank.

4.2. Irish Civil War and National Army

In 1921, O'Duffy supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty, believing it was a necessary step towards a republic and being pessimistic about the IRA's chances if the war continued. Frank Aiken, a future political and military opponent, acknowledged O'Duffy's "Herculean work" for the pro-Treaty cause from the signing of the treaty until the attack on the Four Courts in June 1922, suggesting that without his efforts, the Civil War might not have occurred.

On January 14, Dan Hogan was arrested in Derry by the B Specials. In response, O'Duffy proposed to Michael Collins the kidnapping of one hundred prominent Orangemen in Fermanagh and Tyrone, a raid executed on February 7. On April 22, O'Duffy accused Liam Lynch's 1st Southern Division of withholding arms intended for the Northern IRA, while Lynch blamed O'Duffy for the failure of arms to reach the north.

O'Duffy served as a general in the National Army and was given control of the South-Western Command. During the ensuing Irish Civil War, he was a key architect of the Free State's strategy of seaborne landings in Republican-held areas. He captured Limerick for the Free State in July 1922, before facing resistance in the Battle of Killmallock south of the city. The deep animosities forged during the Civil War would continue to influence O'Duffy throughout his subsequent political career.

5. Public Service

Eoin O'Duffy's public service career was primarily defined by his significant role in shaping the Garda Síochána, the national police force of the Irish Free State.

5.1. Garda Commissioner

In September 1922, facing indiscipline within the newly formed Garda Síochána, Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O'Higgins appointed O'Duffy as Garda Commissioner. O'Duffy resigned from the army to take up this position. He is widely credited as a skilled organizer who was instrumental in the establishment of a largely respected, non-political, and unarmed police force in Ireland. He emphasized a strong Catholic ethos to distinguish the Gardaí from their predecessors, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), often instructing members that their police work was a religious duty, not merely an ordinary job.

O'Duffy was also a staunch opponent of alcohol within the force. In his first public address as Commissioner, he instructed Gardaí to avoid it and encouraged them to join the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association of the Sacred Heart. Although Gardaí were generally not permitted to wear pins on their uniform, O'Duffy made an exception for the Pioneer pin. In 1924, during the Irish Army Mutiny, he was concurrently appointed as General Officer Commanding of the Irish Army, holding both roles until 1925.

In February 1933, following a general election, Executive Council President Éamon de Valera dismissed O'Duffy as Garda Commissioner. De Valera publicly stated in the Dáil that O'Duffy was "likely to be biased in his attitude because of past political affiliations." However, the underlying reason appeared to be the new government's discovery that O'Duffy had been among those who urged the Cumann na nGaedheal government of W. T. Cosgrave to consider a military coup rather than transfer power to the incoming Fianna Fáil administration after the 1932 Irish general election. O'Duffy declined an offer of another position of equivalent rank in the public service. Years later, Ernest Blythe stated that Cosgrave himself had become so concerned by O'Duffy's conduct that he would have dismissed him had he remained in power. Nevertheless, O'Duffy's dismissal was criticized by Cumann na nGaedheal politicians in the Dáil at the time.

6. Involvement in Sport

Eoin O'Duffy was a highly active and influential figure in various sporting organizations across Ireland, particularly within the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA).

6.1. Ulster GAA

O'Duffy was a leading member of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in Ulster. He was appointed secretary of the Ulster Provincial Council in 1912. He later served as Treasurer of the GAA Ulster Council from 1921 to 1934. His significant contributions to the development of the GAA in Ulster are commemorated by the O'Duffy Terrace at St Tiernach's Park in Clones, County Monaghan, the principal provincial stadium. In December 2009, a plaque was erected in O'Duffy's memory in Aughnamullen, unveiled by Tom Daly, the President of the Ulster GAA Council. He was also a member of the Harps' Gaelic football club.

6.2. Other Sports

Beyond his prominent role in Ulster GAA, O'Duffy was active in other sports as well. He served as President of the Irish Amateur Handball Association from 1926 to 1934. He also led the National Athletic and Cycling Association from 1931 to 1934, an organization he had founded in 1922. Additionally, he was President of the Irish Olympic Council from 1931 to 1932.

O'Duffy held a strong belief in the ideal of "cleaned manliness" through sport. He articulated that sport "cultivates in a boy habits of self-control [and] self-denial" and promotes "the cleanest and most wholesome of the instincts of youth." He suggested that a lack of participation in sports could lead some boys to "fail to keep their athleticism, but became weedy youths, smoking too soon, drinking too soon."

7. Ideology and Political Thought

Eoin O'Duffy's political and social thought evolved significantly throughout his career, marked by a strong emphasis on national identity, a belief in the moral benefits of sport, and a later embrace of fascism and staunch anti-communism.

Initially, O'Duffy believed in the ideal of "cleaned manliness," viewing sport as a crucial tool for character development. He stated that sport "cultivates in a boy habits of self-control [and] self-denial" and promotes "the cleanest and most wholesome of the instincts of youth." He warned that a lack of sport could lead to "weedy youths, smoking too soon, drinking too soon."

In the 1930s, O'Duffy became increasingly attracted to the various fascist movements emerging across Europe, particularly admiring Benito Mussolini's Italy. He adopted outward symbols of European fascism, such as the straight-arm Roman salute and distinctive blue uniforms, for his paramilitary organization, the Blueshirts. His new constitution for the Blueshirts promoted corporatism, Irish unification, and opposition to "alien" control and influence. His embrace of fascism was rooted in a belief in a "corporate system" that he saw as an alternative to both Marxism and capitalism.

O'Duffy was a devout anti-communist, viewing the Spanish Civil War as a conflict "between Christ and antichrist" and perceiving the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as a communist group. While he admired Italian fascism, he expressed a preference for it over German Nazism, stating that "the Nazi policy is not compatible with the corporative system." He also publicly argued against antisemitism at the 1934 International Fascist conference in Montreux, asserting that Ireland had "no Jewish problem" and that he "could not subscribe to the principle of the persecution of any race." However, his later book, Crusade in Spain, contained antisemitic undertones, describing trade unions as "powerful political Jewish-Masonic organisations, directed and focused by the Communist International." This demonstrates a complex and at times contradictory ideological stance, ultimately leaning towards authoritarian and nationalist ideals.

8. Political Activities

Eoin O'Duffy's political activities were marked by his leadership of paramilitary and political movements, and his attempts to influence Irish politics during the inter-war period, culminating in his controversial involvement in the Spanish Civil War.

8.1. Leader of the Blueshirts

In July 1933, urged by Ernest Blythe and Thomas F. O'Higgins, O'Duffy assumed leadership of the Army Comrades Association (ACA). This organization was formed to protect public meetings of Cumann na nGaedheal, which had been disrupted by Irish Republican Army members under the slogan "No Free Speech for Traitors." O'Duffy, along with many other conservative elements within the Irish Free State, began to embrace fascist ideology, which was fashionable at the time. O'Duffy was considered an ideal choice to lead the ACA due to his charisma, organizational skills, and his perceived untainted reputation from the failures of the previous Cumann na nGaedheal government.

O'Duffy's leadership of the ACA was approved on July 20. He swiftly renamed the movement the National Guard. An admirer of Italian leader Benito Mussolini, O'Duffy and his organization adopted outward symbols of European fascism, such as the straight-arm Roman salute and a distinctive blue uniform, quickly earning them the nickname Blueshirts, akin to the Italian Blackshirts and German Brownshirts. O'Duffy launched a weekly newspaper, the Blueshirt, and published a new constitution advocating corporatism, Irish unification, and opposition to "alien" control and influence.

In July 1933, O'Duffy announced plans for a Blueshirt parade in Dublin to commemorate Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, and Kevin O'Higgins. An annual march to Leinster Lawn had been held for these pro-Treaty nationalists until Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932. Éamon de Valera feared a similar coup d'état to those seen in Italy. The Special Branch raided the homes of prominent Cumann na nGaedheal figures to seize their firearms. On August 11, de Valera reinstated the Constitution (Amendment No. 17) Act 1931, banned the parade, and deployed Gardaí to key locations. Forty-eight hours before the planned march, 200 men were recruited into an auxiliary special branch of the police, soon nicknamed the Broy Harriers.

On August 22, the Blueshirts were declared an illegal organization. To circumvent this ban, the movement adopted another new name, the League of Youth. In 1933, a group of Irish republicans, including Dan Keating, planned to assassinate O'Duffy in Ballyseedy, County Kerry, while he was en route to a meeting. However, a man sent to Limerick purposely provided false information, allowing O'Duffy to escape.

During the early stages of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935, O'Duffy offered Benito Mussolini the service of 1,000 Blueshirts, believing the conflict represented a struggle between civilization and barbarism. In a September 18 interview, he stated that the Blueshirts were volunteering to fight "not for Italy or against Abyssinia, but for the principle of the corporate system" against which "the forces of both Marxism and of capitalism" were arrayed. O'Duffy and some of his men also attended the 1934 International Fascist conference in Montreux, where he notably argued against antisemitism, stating they had "no Jewish problem in Ireland" and he "could not subscribe to the principle of the persecution of any race." Upon his return to Ireland, he indicated his preference for Italian fascism over German Nazism, stating that "the Nazi policy is not compatible with the corporative system."

8.2. Leader of Fine Gael

On August 24, 1933, representatives of Cumann na nGaedheal and the National Centre Party approached O'Duffy, proposing that the Blueshirts merge with their parties in exchange for O'Duffy becoming their leader. Under pressure from de Valera's ban on the organization, the Blueshirts approved the merger on September 8, leading to the formation of Fine Gael from Cumann na nGaedheal, the Centre Party, and the Blueshirt movement. Although not a TD, O'Duffy became the new party's first leader, with W. T. Cosgrave serving as Vice President and parliamentary leader. The National Guard, now renamed the Young Ireland Association, transitioned from an illegal paramilitary group into the militant wing of a political party.

The new party's policy document, published in mid-November 1933, aimed for the reunification of Ireland within the British Commonwealth but conspicuously omitted any mention of a corporatist parliament and explicitly committed itself to democracy. As a result, O'Duffy was compelled to moderate his anti-democratic rhetoric, although many of his Blueshirt colleagues continued to advocate authoritarianism.

Fine Gael meetings frequently faced attacks from IRA members, and O'Duffy's tours of rural towns often led to heightened tensions and violence. On October 6, 1933, O'Duffy was involved in disturbances in Tralee, where he was struck on the head with a hammer and had his car torched while attempting to attend a Fine Gael convention. De Valera used this violence to justify a crackdown on Blueshirt activities. A raid on the Young Ireland Association found evidence that it was merely the National Guard under a new name, leading to the organization being banned once again. O'Duffy responded with a speech in Ballyshannon, referring to himself as a republican and declaring that "whenever Mr de Valera runs away from the Republic and arrests you Republicans, and puts you on board beds in Mountjoy, he is entitled to the fate he gave Mick Collins and Kevin O'Higgins." He was arrested by the Gardaí several days later, initially released on appeal, but then summoned before the Military Tribunal on charges of membership in an illegal organization and incitement to murder the president of the executive council; however, he was not convicted of either charge.

O'Duffy proved to be an unsuitable leader for a political party. He was primarily a soldier rather than a politician and possessed a temperamental nature. He resented Cumann na nGaedheal's shift away from republicanism after Collins' death in 1922, insisting that Fine Gael would not "play second fiddle to anybody in the matter of Nationality." O'Duffy's strong nationalistic views alienated former Unionists who had supported Cumann na nGaedheal since the Civil War and alarmed pro-Commonwealth moderates within Fine Gael. This also resulted in an exclusion order being placed on him in Northern Ireland. O'Duffy also clashed with his party on economic policy; while Fine Gael favored a return to pasture farming and free trade, O'Duffy supported the experiments in tillage and protectionism implemented by his Fianna Fáil rivals, forcing him to seek a difficult compromise.

His Fine Gael colleagues, who saw themselves as defenders of law-and-order, were embarrassed by the Blueshirts' use of violence and attacks on the Gardaí, as well as O'Duffy's connections with foreign fascist organizations and his view of the IRA as a communist group. O'Duffy's prestige suffered when Fine Gael only secured majorities on six councils compared to Fianna Fáil's fifteen in the 1934 Irish local elections, despite O'Duffy's prediction of winning twenty. The financial cost of Blueshirt activism also began to strain the party. O'Duffy's approval of illegal agitation against the government's collection of land annuities, his declaration of support for a republic, and the revelation of his connections with the British Union of Fascists and the Fedrelandslaget were the final catalysts for moderates in Fine Gael. On September 5 and 7, 1934, Cosgrave, Ned Cronin, and James Dillon met with O'Duffy, resulting in an agreement that O'Duffy would "deliver only carefully prepared and concise speeches from manuscripts" and give interviews "only after consultation and in writing." In response, O'Duffy resigned from the party on September 18. After his resignation, O'Duffy denounced Fine Gael as "the pan-British party of the Free State" and claimed he resigned "because he was not prepared to lead the League of Youth with the Union Jack tied to his neck."

8.3. Spanish Civil War Participation

Initially, O'Duffy publicly stated he was "glad to be out of politics" after his resignation from Fine Gael. However, in October 1934, he announced his intention to lead the Blueshirts as an independent movement. The Blueshirts subsequently split into two factions, one supporting O'Duffy and the other backing Ned Cronin's leadership. O'Duffy and Cronin toured the country, attempting to gain the support of local Blueshirt branches. By 1935, the Blueshirts had largely disintegrated. Seeking to regain his former political influence, O'Duffy attempted to court the IRA, encouraging his followers to wear Easter lilies and to refrain from informing on republicans. In June 1935, O'Duffy launched the National Corporate Party, a fascist political party directly inspired by Benito Mussolini's Italy.

The following year, he organized an Irish Brigade to fight for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. His motivations were rooted in Ireland's historic link with Spain, his fervent anti-communism, and a desire to defend Catholicism. He famously declared the conflict "is not a conflict between fascism and anti-fascism but between Christ and antichrist." In London in September 1936, O'Duffy met Juan de la Cierva and Emilio Mola, promising to recruit an Irish contingent to fight against the Republicans.

Despite the Irish Government advising against participation in the war, approximately 700 of O'Duffy's followers traveled to Spain to fight on the Nationalist side. O'Duffy later claimed to have received over 7,000 applications, but various complications meant only about 700 made it to Spain. O'Duffy's men saw limited fighting, and the brigade was eventually sent home by Nationalist leader Francisco Franco, returning in June 1937. Franco was reportedly unimpressed by the Brigade's lack of military expertise, and there were significant internal disputes among O'Duffy and his officers regarding the Brigade's direction.

9. Later Life and Death

Upon his return to Ireland from Spain, O'Duffy's political standing was in disarray. He authored a book, Crusade in Spain (1938), detailing the Irish Brigade's experiences. The book contained antisemitic undertones, with O'Duffy writing that trade unions were "powerful political Jewish-Masonic organisations, directed and focused by the Communist International." He later congratulated General Franco on his victory in the Spanish Civil War, with Franco thanking O'Duffy for his congratulations "on the victory of the Spanish Army in defence of Christianity, occidental civilisation and humanity, over the forces of destruction and disorder."

In 1936, O'Duffy attended the founding meeting of Cumann Poblachta na hÉireann but never became a member. In 1940, he also attended the founding meeting of Córas na Poblachta alongside former leaders of the Irish Christian Front. In 1939, The Irish Times reported that O'Duffy and his followers were attempting to establish a new organization, though nothing materialized. He was subsequently placed under surveillance by the G2, the Irish military intelligence service.

In February 1939, O'Duffy met with Oskar Pfaus, a German spy, whom he connected with the IRA. He also met the Italian diplomat Vincenzo Berardis, who assessed O'Duffy as a committed fascist, noting his approval of the S-Plan and his opposition to de Valera's coercion against the IRA. A month later, O'Duffy met Berardis again to seek support for a new fascist party that would unite Irish fascists and republicans. G2 suspected O'Duffy was "flirting with the IRA" by acting as a negotiator between them and the Germans, and he is thought to have met with several leading IRA figures and German diplomat Eduard Hempel in a remote part of County Donegal during the summer of 1939. At one point, O'Duffy was offered a position as an IRA intelligence officer and was invited to join former IRA Chiefs of Staff Moss Twomey and Andy Cooney in a protest against the "Yankee invasion of the Six Counties" in the summer of 1941.

In early November 1940, O'Duffy spoke with German spy Hermann Goertz in a meeting arranged by Seamus O'Donovan. O'Duffy made a positive impression on Goertz and introduced him to General Hugo MacNeill. MacNeill subsequently met with O'Duffy and German diplomat Henning Thomsen the following month to draft a bilateral understanding between the Irish army and Germany in the event of a British invasion of Ireland. In February-March 1943, transmissions purportedly from an associate of O'Duffy were sent using Goertz's code to the Abwehr in Berlin, offering to raise a 'Green Division' of volunteers to fight alongside the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front against Bolshevism. However, this telegram was sent by Joseph Andrews, a man unconnected to O'Duffy, who was attempting to extract money from the Germans. Andrews was arrested in Dublin in December 1943, and O'Duffy was unaware of the proposal made in his name.

By this time, O'Duffy had developed a serious drinking problem, and his health began to seriously deteriorate. He died on November 30, 1944, at the age of 54. He received a state funeral. Following a Requiem Mass in St Mary's Pro-Cathedral, he was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. In 2006, RTÉ aired a documentary titled Eoin O'Duffy - An Irish Fascist.

10. Assessment and Controversy

Eoin O'Duffy's legacy is a subject of considerable debate, marked by both his recognized organizational skills and significant criticisms regarding his political ideologies and actions.

10.1. Positive Contributions

O'Duffy is acknowledged for his strong organizational abilities, which were evident throughout his early military career. His rapid rise through the ranks of the IRA and his effectiveness in commanding units during the Irish War of Independence demonstrate his leadership capabilities. Furthermore, he is widely credited with playing a crucial role in establishing the Garda Síochána, the police force of the Irish Free State. His efforts helped shape the Gardaí into a largely respected, non-political, and unarmed force, contributing significantly to the stability of the nascent state. His contributions to the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) and other Irish sporting bodies are also noted as positive influences on Irish cultural and athletic development.

10.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his early contributions, O'Duffy's later career is marred by significant criticisms and controversies. His actions during the War of Independence, particularly the arms raids on Protestant homes and the retaliatory violence in Rosslea, contributed to sectarian tensions and resulted in civilian casualties.

His most profound criticisms stem from his embrace of fascism in the 1930s. As leader of the Blueshirts, he adopted symbols and rhetoric associated with European authoritarian movements, and his organization engaged in violence against political opponents. His brief leadership of Fine Gael was characterized by clashes with party moderates over his continued authoritarian leanings and connections with foreign fascist organizations. His anti-democratic rhetoric and attempts to undermine the democratic process, such as allegedly urging a military coup in 1932, are major points of contention.

O'Duffy's decision to lead the Irish Brigade to fight for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War further cemented his association with controversial ideologies. His justification of the war as a battle between "Christ and antichrist" and his later book, Crusade in Spain, which contained antisemitic undertones, reflect a troubling ideological stance that clashed with principles of human rights and civil liberties. His clandestine involvement with pro-Axis circles during World War II also raises concerns about his alignment with totalitarian regimes. Overall, O'Duffy's legacy is critically viewed for his shift towards authoritarianism, his role in sectarian violence, and his embrace of ideologies that undermined democratic values and human rights in Ireland.

11. Legacy and Impact

Eoin O'Duffy's legacy remains a complex and often debated aspect of Irish history. While initially celebrated as a hero of the Irish War of Independence and the architect of the Garda Síochána, his later embrace of fascism and his controversial political activities profoundly impacted his historical memory. His leadership of the Blueshirts introduced overt fascist symbols and rhetoric into Irish political discourse, contributing to a period of significant political instability and violence in the 1930s. This period highlighted deep divisions within Irish society regarding democracy, authority, and national identity.

His involvement in the Spanish Civil War further solidified his image as a figure aligned with authoritarian movements, despite his claims of defending Catholicism. This action, undertaken against the advice of the Irish government, underscored a tension between Irish neutrality and ideological allegiances during a tumultuous global period. O'Duffy's later attempts to engage with German intelligence during World War II, though ultimately ineffective, further complicate his legacy, associating him with pro-Axis sentiments.

Today, O'Duffy is largely remembered as a cautionary figure, a symbol of the authoritarian temptations that emerged in the inter-war period. His trajectory from a respected military and public servant to a controversial fascist leader serves as a reminder of the challenges to democracy and human rights in newly independent states. While his early organizational skills are acknowledged, his later actions and ideologies continue to provoke critical assessment, shaping a legacy that emphasizes the importance of democratic values and civil liberties in Irish society.