1. Overview

Enshakushanna, also known as Enshagsagana, En-shag-kush-ana, Enukduanna, or En-Shakansha-Ana, was a significant king of Uruk during the mid-3rd millennium BC. He is listed in the Sumerian King List, which attributes a reign of 60 years to him. His rule was marked by extensive military campaigns, leading to the conquest of major city-states such as Hamazi, Akkad, Kish, and Nippur. Through these conquests, Enshakushanna asserted his hegemony over all of Sumer. He was the first ruler to adopt the influential Sumerian title `Lugal kalam ma.KISumerian`, meaning "King of all the Land," a title that would later evolve into "King of Sumer and Akkad" and signify broader control over Mesopotamia.

2. Life

Enshakushanna's life and reign are primarily understood through inscriptions and later historical records, which highlight his military prowess and the establishment of new royal titulature.

2.1. Early Life and Background

Enshakushanna is associated with the Second Dynasty of Uruk. According to the Sumerian King List, he was the initial king of this dynasty. However, modern scholarship suggests that the Sumerian King List's account of the Uruk Second Dynasty may be incomplete and chronologically inaccurate. There is a strong theory that Enshakushanna reigned much closer to the period of the Akkadian Empire, rather than at the beginning of the Second Dynasty. His father is identified as Elilina, who may have been Elulu, a king of Ur.

2.2. Reign and Conquests

Enshakushanna's reign was largely defined by his military campaigns and territorial expansion. He successfully conquered several prominent city-states, including Hamazi, Akkad, Kish, and Nippur, thereby establishing Uruk's dominance over Sumer.

One of his most notable military actions was the campaign against Kish and Akshak. This event is documented on a stone bowl found at Nippur, which details his victory:

For Enlil, king of all lands,

Enshakushanna, lord of the land of Sumer and king of the nation

when the gods commanded him,

he sacked Kish

(and) captured Enbi-Ishtar, the king of Kish.

The leader of Kish and the leader of Akshak, (when) both their cities were destroyed ...

(Lacuna)

in (?) [..] he returned to them,

but [he] dedicated their statues, their precious metals and lapis lazuli, their timber and treasure, to the god Enlil at Nippur.

This account indicates a decisive victory over Kish, leading to the capture of its king, Enbi-Ishtar, and the destruction of both Kish and Akshak. Archaeological evidence at Kish, particularly the EDIIIb destruction layers at Palace A and the Plano-Convex Building, supports a "pervasive violent destruction of the city of Kish at the end of the ED IIIb" period, which many scholars attribute to Enshakushanna's campaign. This act of city destruction is considered one of the earliest recorded instances of such an order in history.

Beyond his northern campaigns, Enshakushanna also attacked Akkad. A year name from his reign explicitly states, "Year in which En-šakušuana defeated Akkad." This victory occurred shortly before the rise of the Akkadian Empire, highlighting his significant influence in the region during a pivotal period.

3. Titulature

Enshakushanna was a pivotal figure in the development of Sumerian royal titles. He was the first ruler to adopt the Sumerian title `en ki-en-gi lugal kalamSumerian` (also transliterated as `Lugal kalam ma.KISumerian`). This title can be translated as "lord of Sumer and king of all the land." It has also been interpreted as "en of the region of Uruk and lugal of the region of Ur," suggesting a dual authority over both religious and secular domains, or over distinct geographical areas.

The adoption of "King of all the Land" was a significant innovation in Mesopotamian political thought. This title laid the groundwork for later, more comprehensive claims to regional hegemony. It is considered a precursor to the later and more widely recognized title `lugal ki-en-gi ki-uriSumerian`, or "King of Sumer and Akkad", which eventually came to signify kingship over the entirety of Mesopotamia. This demonstrates Enshakushanna's lasting impact on the conceptualization of royal power and territorial control in the ancient Near East.

4. Sumerian King List and Chronological Issues

Enshakushanna's placement and the duration of his reign in the Sumerian King List have been subjects of considerable scholarly debate. The Sumerian King List states that he reigned for 60 years and was the first king of the Second Dynasty of Uruk. However, the accuracy of the King List for the Second Dynasty of Uruk is questioned by modern scholarship, which suggests that its compilers had limited knowledge of the kings from this period, leading to significant omissions and potential chronological errors.

Recent archaeological findings and linguistic analyses have led to a reevaluation of Enshakushanna's chronological position. Evidence, such as the appearance of the same individuals in administrative documents from both Enshakushanna's era and the reign of Sargon of Akkad, along with the observation that the Sumerian language from Enshakushanna's time shows little change from that of Sargon's period, suggests that Enshakushanna's reign was much closer to the Akkadian Empire than previously thought. This challenges the King List's portrayal of him as the initial ruler of the Second Dynasty of Uruk. Consequently, the succession order of kings within the Second Dynasty of Uruk, including figures like Lugal-kisalsi and Lugal-kinishe-dudu, is undergoing significant revision among historians.

5. Succession and Political Context

Following Enshakushanna's reign, the succession in Uruk is somewhat debated, with some sources suggesting Girimesi as his successor, while others name Lugal-kinishe-dudu. Regardless of the immediate successor, the hegemony over Sumer appears to have shifted away from Uruk for a period, passing to Eannatum of Lagash. This indicates a dynamic political landscape where power frequently changed hands among the leading city-states.

Despite this shift, Uruk remained an important player. Lugal-kinishe-dudu, a later king of Uruk, formed an alliance with Entemena, a successor of Eannatum, demonstrating continued political maneuvering and coalition-building among the Sumerian city-states. This alliance was notably directed against Lagash's primary rival, Umma, illustrating the ongoing conflicts and rivalries that characterized the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia.

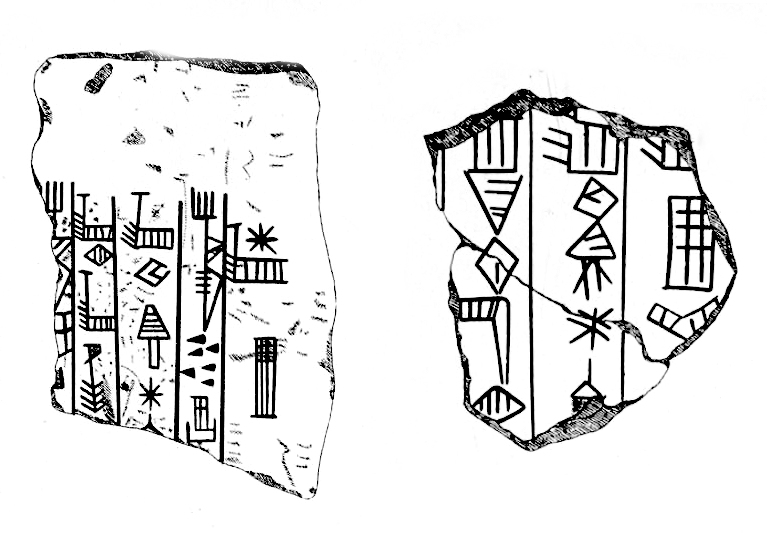

6. Inscriptions and Artifacts

Several inscriptions bearing Enshakushanna's name have been discovered, providing direct archaeological evidence of his existence and reign. Among these is a significant dedication tablet, which is currently housed in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation.

The inscription on this tablet reads:

`𒀭𒇽𒆪𒊏 / 𒂗𒊮𒀭𒈾 /𒂗 𒆠𒂗𒄀 / 𒈗 𒌦𒈣 / 𒌉𒂍𒇷𒇷𒈾 / 𒂍𒉌𒈬𒈾𒆕Sumerian`

Its transliteration and translation are:

`DingirLU2-KU-ra / en-sha3-kush2-an-na / en ki-en-gi / lugal kalam-ma / dumu e2-li-li-na#? / e2-ni mu-na-du3Sumerian`

"For ... (unknown god): Enshakushanna, lord of Sumer and king of all the land, son of Elilina, built the temple for Him."

This inscription not only confirms his titles but also identifies his father as "Elilina." Scholars suggest that "Elilina" might refer to King Elulu of Ur, further connecting Enshakushanna to a broader network of early Mesopotamian royalty. The tablet serves as a crucial artifact for understanding his reign and the political and religious practices of his time.

Other fragments also bear his name, providing additional textual evidence of his activities and confirming his historical presence as a ruler who left a tangible mark on the archaeological record.

7. Assessment

Enshakushanna's reign represents a critical period in early Mesopotamian history, characterized by military expansion and the formalization of royal authority.

7.1. Historical Significance and Impact

Enshakushanna's historical significance lies primarily in his military achievements and his innovative use of royal titulature. His successful campaigns against powerful city-states like Kish, Akkad, Hamazi, and Nippur demonstrate Uruk's ascendancy and his ability to establish a broad hegemony over Sumer. These conquests were not merely territorial gains but also involved the capture of rival kings and the acquisition of vast wealth, which he dedicated to the god Enlil at Nippur.

Perhaps his most lasting legacy is the introduction of the title `Lugal kalam ma.KISumerian`, "King of all the Land." This title was a groundbreaking assertion of comprehensive sovereignty, moving beyond local city-state rule to claim authority over a wider geographic and political entity. This concept of overarching kingship profoundly influenced subsequent rulers, including Lugal-zage-si of Umma, who also claimed control over all Sumer, and most notably, Sargon of Akkad, whose Akkadian Empire would later unify Mesopotamia under a single rule, adopting and evolving similar universalistic titles. Enshakushanna's pioneering use of this title thus marks an important step towards the eventual political unification of Mesopotamia.

7.2. Criticism and Controversy

Despite his achievements, Enshakushanna's reign is not without controversy, particularly regarding the dating of his rule and his destructive actions. The Sumerian King List's placement of him as the first king of the Second Dynasty of Uruk and its attribution of a 60-year reign are widely debated by modern scholars. Evidence suggesting his reign was much closer to the Akkadian Empire challenges the traditional chronology and highlights the limitations of the Sumerian King List as a sole historical source. This ongoing scholarly debate underscores the challenges in reconstructing precise chronological sequences for early Mesopotamian history.

Furthermore, Enshakushanna's documented order to destroy the city of Kish after his victory over its king, Enbi-Ishtar, stands as a notable point of criticism. This act, supported by archaeological evidence of widespread destruction layers at Kish, is considered one of the earliest recorded instances of a deliberate and pervasive city destruction order in history. While such actions were part of ancient warfare, the explicit command to "sacked Kish" and the subsequent dedication of its treasures to Enlil at Nippur reflect a harsh imposition of power. This event serves as a stark reminder of the brutal realities of inter-city conflicts in Early Dynastic Mesopotamia and raises questions about the human cost of asserting hegemony during this period.