1. Life

1.1. Early Life and Education

Emanuel Lasker was born on December 24, 1868, in Berlinchen in Neumark (now Barlinek in Poland). His father was a Jewish cantor. At the age of eleven, he was sent to Berlin to study mathematics, where he lived with his elder brother, Berthold Lasker, who was eight years his senior and introduced him to chess. Berthold himself was a top-ten chess player globally in the early 1890s. To supplement their income, Emanuel often played chess and card games for small stakes, particularly at the Café Kaiserhof.

Lasker achieved early success by winning the Café Kaiserhof's annual Winter tournament in 1888-89. This was followed by a victory in the Hauptturnier A (a "second division" tournament) at the sixth DSB Congress (German Chess Federation's congress) held in Breslau. His win in the Hauptturnier earned him the esteemed title of "master," allowing him to compete in higher-level tournaments and effectively launching his professional chess career. He defeated Viennese amateur von Feierfeil in a playoff after they tied in the final round.

1.2. Early Career

After becoming a master, Lasker quickly demonstrated his prowess. He finished second in an international tournament in Amsterdam in 1889, placing ahead of notable players like Mason and Gunsberg. In the spring of 1892, he won two tournaments in London, notably achieving victory in the stronger of the two without a single loss. In New York City in 1893, Lasker achieved a perfect score, winning all thirteen games, a rare feat in significant chess tournaments.

His early match record was equally impressive. In 1890, he drew a short playoff match against his brother Berthold in Berlin. From 1889 to 1893, he won all his other matches, mostly against top-tier opponents, including Curt von Bardeleben (1889), Jacques Mieses (1889), Henry Edward Bird (1890), Berthold Englisch (1890), Joseph Henry Blackburne (1892), Jackson Showalter (1892-93), and Celso Golmayo Zúpide (1893).

In 1892, Lasker founded The London Chess Fortnightly, one of his first chess magazines, which ran until July 1893. Soon after its final issue, he relocated to the United States, where he resided for the next two years. During this period, Lasker challenged Siegbert Tarrasch, who had won three consecutive strong international tournaments (Breslau 1889, Manchester 1890, and Dresden 1892), to a match. However, Tarrasch haughtily declined, insisting that Lasker first prove himself by winning one or two major international events.

1.3. Ascension to World Champion and Defense

After being rebuffed by Tarrasch, Emanuel Lasker sought to challenge the reigning World Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, for the title. This marked the beginning of his remarkable reign as the world champion.

1.3.1. Matches against Steinitz

Lasker initially proposed a stake of 5.00 K USD per side for the World Chess Championship match against Steinitz. Although an agreement was reached for 3.00 K USD per side, the final stake was reduced to 2.00 K USD due to Lasker's difficulty in raising the money. This amount was notably less than for some of Steinitz's previous matches; the combined stake of 4.00 K USD in 1894 would be equivalent to over 495.00 K USD in 2006.

The World Chess Championship 1894 match was held across venues in New York, Philadelphia, and Montreal. Despite Steinitz's confident prediction of an easy victory, Lasker shocked the chess world by winning the first game. Steinitz recovered in the second, maintaining balance until the sixth game. However, Lasker secured five consecutive wins from the seventh to the eleventh games, prompting Steinitz to request a week's rest. Upon resumption, Steinitz showed improved form, winning the 13th and 14th games, but he could not overcome Lasker's substantial lead from the middle of the match. Lasker convincingly won with a final score of ten wins, five losses, and four draws. On May 26, 1894, Lasker officially became the second recognized World Chess Champion. He further solidified his claim by defeating Steinitz even more decisively in their rematch in Moscow in 1896-97, with a score of ten wins, two losses, and five draws.

1.3.2. Tournament Successes

Despite Lasker's clear victories over Steinitz, influential players and journalists, including Gunsberg, Leopold Hoffer, and notably Siegbert Tarrasch, downplayed the significance of the 1894 match. They claimed Lasker won primarily because Steinitz was advanced in age (58 in 1894). Tarrasch, who had previously declined Lasker's challenge in 1892 by insisting Lasker win a major international tournament first, also criticized that Lasker had not yet played against the other top players of the time, such as Tarrasch himself and Mikhail Chigorin.

Lasker responded to these criticisms by compiling an even more impressive playing record. He took third place at Hastings 1895 chess tournament, finishing behind Harry Nelson Pillsbury and Chigorin, but ahead of Tarrasch and Steinitz. He then secured first prizes in several very strong international tournaments: St. Petersburg 1895-96 (an elite four-player tournament where he finished ahead of Steinitz, Pillsbury, and Chigorin), Nuremberg (1896), London (1899), and Paris (1900). He also tied for second at Cambridge Springs 1904 and tied for first at the Chigorin Memorial in St. Petersburg 1909. In 1906, he won a weaker tournament at Trenton Falls.

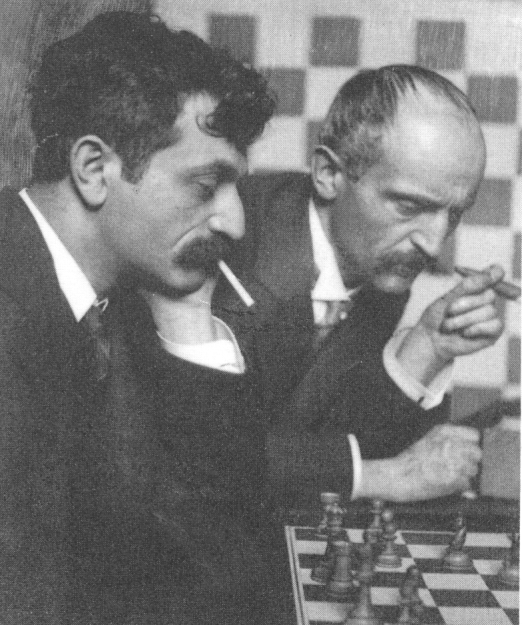

A highlight of his tournament career came at St. Petersburg (1914), where he overcame a 1½-point deficit to finish ahead of the rising stars, José Raúl Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine, both of whom would later become World Champions. For decades, it was reported that Tsar Nicholas II of Russia conferred the title of Grandmaster of Chess upon the five finalists of this tournament (Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch, and Marshall). However, chess historian Edward Winter has questioned this account, noting that the earliest sources supporting this story were published significantly later, in 1940 and 1942.

1.3.3. Major Defense Matches

Between his rematch with Steinitz in 1896-97 and 1914, Lasker maintained an impressive match record, winning all but one of his regular matches, with three of these being decisive defenses of his World Championship title. A planned World Championship match against Géza Maróczy in 1906 failed to materialize due to unfinalized arrangements.

Lasker's first World Championship defense since 1897 was against Frank Marshall in the World Chess Championship 1907. Despite Marshall's aggressive playing style, he was unable to win a single game, ultimately losing the match by a score of 11½-3½ (eight losses, seven draws).

He then faced Siegbert Tarrasch in the World Chess Championship 1908, with games played in Düsseldorf and Munich. Tarrasch, a proponent of rigid chess principles, viewed Lasker as a mere "coffeehouse player" who won through dubious tricks. Lasker, in turn, ridiculed Tarrasch's arrogance, considering him more suited for salons than the chessboard. At the opening ceremony, Tarrasch famously refused to engage with Lasker, stating only: "Mr. Lasker, I have only three words to say to you: check and mate!" Lasker responded by dominating the match, winning four of the first five games with a style Tarrasch found incomprehensible. For instance, in the second game, after 19 moves, Lasker was a pawn down with a bad bishop and doubled pawns, a position seemingly advantageous for Tarrasch. Yet, 20 moves later, Tarrasch was compelled to resign. Lasker ultimately secured a decisive victory with a score of 10½-5½ (eight wins, five draws, three losses). Tarrasch later humorously attributed his defeat to the wet weather.

In 1909, Lasker played two matches against Dawid Janowski, a Polish expatriate known for his all-out attacking style. The first was a short exhibition match in Paris, which ended in a 2-2 draw (two wins, two losses). Several months later, they played a longer match in Paris, which some chess historians regard as a World Chess Championship match, while others consider it an exhibition. Understanding Janowski's aggressive nature, Lasker employed a solid defensive strategy that led Janowski to launch his attacks prematurely, leaving him vulnerable. Lasker easily won this match 8-2 (seven wins, two draws, one loss). Unconvinced, Janowski requested a rematch, which Lasker accepted. The World Chess Championship match took place in Berlin in November-December 1910. Lasker decisively crushed Janowski with a score of 9½-1½ (eight wins, three draws, no losses). Janowski, perplexed by Lasker's moves, reportedly told Edward Lasker, "Your homonym plays so stupidly that I cannot even look at the chessboard when he thinks. I am afraid I will not do anything good in this match."

Between his two matches against Janowski, Lasker organized another World Chess Championship in January-February 1910 against Carl Schlechter. Schlechter was known for his modest demeanor and peaceful playing style, frequently accepting draw offers (approximately 80% of his games ended in draws), which made him unlikely to win major tournaments by a decisive margin. Lasker initially sought to attack, but Schlechter's defense was impenetrable, leading to four consecutive draws. In the fifth game, Lasker held a significant advantage but committed a blunder that cost him the game, putting Schlechter one point ahead midway through the match. The subsequent four games were hard-fought draws. In the sixth, Schlechter managed a draw despite being a pawn down, and in the seventh, Lasker narrowly avoided a loss due to a brilliant exchange sacrifice by Schlechter. In the ninth game, only a blunder by Lasker allowed Schlechter to draw an otherwise lost ending. With the score 5-4 in Schlechter's favor before the final game, it was a critical moment. In the tenth game, Schlechter pursued a tactical win and gained a large advantage, but he missed a clear winning line on the 35th move. He continued to take increasing risks and eventually lost the game. As a result, the match ended in a 5-5 draw, and Lasker retained his World Champion title. It was speculated that Schlechter took unusual risks in the tenth game because the match terms required him to win by a two-game margin. However, Isaak and Vladimir Linder, citing Austrian chess historian Michael Ehn, suggest this was unlikely, as Lasker agreed to waive the two-game provision when the match was reduced to only 10 games. Ehn quoted Schlechter's comment in the Allgemeine Sportzeitung (ASZ) of December 9, 1909: "There will be ten games in all. The winner on points will receive the title of world champion. If the points are equal, the decision will be made by the arbiter."

1.3.4. Abandoned Challenges

In 1911, Lasker received a challenge for a world title match from the rising star José Raúl Capablanca. Lasker was hesitant to play the traditional "first to win ten games" match in the semi-tropical climate of Havana, especially as draws were becoming more frequent, potentially extending the match for over six months. He proposed alternative conditions: the match should be limited to the best of thirty games, counting draws; if neither player held a lead of at least two games by the end, it would be considered a draw; if either player won six games and led by at least two games before thirty games, they would be declared the winner; the champion would decide the venue and stakes and have exclusive publication rights; the challenger would deposit a forfeit of 2.00 K USD (equivalent to over 250.00 K USD in 2020 values); and a time limit of twelve moves per hour, with play limited to two 2½-hour sessions daily, five days a week.

Capablanca objected to several of these conditions, particularly the time limit, the short playing sessions, the thirty-game limit, and especially the requirement to win by a two-game margin to claim the title, which he deemed unfair. Lasker took offense at the tone of Capablanca's criticism, leading him to break off negotiations. Until 1914, Lasker and Capablanca were not on speaking terms. However, at the 1914 St. Petersburg tournament, Capablanca proposed a revised set of rules for World Championship matches, which were accepted by all leading players, including Lasker.

In late 1912, Lasker also began negotiations for a world title match with Akiba Rubinstein, whose tournament record had been on par with Lasker's and slightly ahead of Capablanca's in recent years. An agreement was made for a match if Rubinstein could secure the necessary funds. Unfortunately, Rubinstein lacked wealthy backers, and the match never took place, highlighting a significant flaw in the championship system of the era. The outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914 ultimately ended any immediate hopes of Lasker playing either Rubinstein or Capablanca for the World Championship.

1.3.5. During World War I

Throughout World War I (1914-1918), Lasker participated in only two serious chess events. In 1916, he convincingly defeated Tarrasch in a non-title match, with a score of 5½-½. In September-October 1918, shortly before the armistice, Lasker won a quadrangular (four-player) tournament in Berlin, finishing half a point ahead of Rubinstein.

During this period, Lasker invested all his savings in German war bonds, which subsequently lost almost all their value due to wartime and post-war inflation. He also wrote a controversial pamphlet arguing that civilization would be imperiled if Germany lost the war.

1.4. Academic and Philosophical Activities

Despite his exceptional chess achievements, Lasker's intellectual pursuits extended far beyond the game. His parents recognized his strong intellectual talents, particularly in mathematics, and sent him to study in Berlin, where he also discovered his aptitude for chess. Lasker earned his abitur (high school graduation certificate) in Landsberg an der Warthe (now Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland, but then part of Prussia). He continued his studies in mathematics and philosophy at universities in Berlin, Göttingen (where David Hilbert was one of his doctoral advisors), and Heidelberg.

In 1895, he published two mathematical articles in the prestigious journal Nature. Following the advice of David Hilbert, Lasker enrolled in doctoral studies at Erlangen from 1900 to 1902. In 1901, he submitted his doctoral thesis, Über Reihen auf der Convergenzgrenze ("On Series at Convergence Boundaries"), at Erlangen, and it was subsequently published by the Royal Society in the same year. He was awarded a doctorate in mathematics in 1902. His most significant mathematical work, published in 1905, introduced a theorem on primary decompositions of ideals. This theorem was later generalized by Emmy Noether and is now considered of fundamental importance to modern algebra and algebraic geometry. Rings possessing this "primary decomposition property" are known as "Laskerian rings" in his honor.

Lasker held brief teaching positions as a mathematics lecturer at Tulane University in New Orleans (1893) and Victoria University in Manchester (1901). However, he was unable to secure a long-term academic position, which led him to pursue his scholarly interests independently.

In 1906, Lasker published a booklet titled Kampf (Struggle), in which he attempted to formulate a universal theory of all competitive activities, encompassing chess, business, and even warfare. He followed this with two other books classified as philosophical works: Das Begreifen der Welt (Comprehending the World; 1913) and Die Philosophie des Unvollendbar (The Philosophy of the Unattainable; 1918). Despite their intellectual ambition, these philosophical writings, along with a drama he co-wrote, received limited attention from the wider public and academic community. He also approached political issues through the lens of chess principles, seeking to develop solutions for societal problems.

1.5. Other Activities and Personal Life (1894-1918)

In 1896-97, Lasker published his influential book Common Sense in Chess, which was based on a series of lectures he had delivered in London in 1895.

In 1903, Lasker participated in a six-game match against Mikhail Chigorin in Ostend. This match was sponsored by the wealthy lawyer and industrialist Isaac Rice to test the Rice Gambit. Lasker narrowly lost the match. Three years later, he became the secretary of the Rice Gambit Association, founded by Rice to promote the gambit. In 1907, Lasker publicly endorsed Rice's views on the convergence of chess and military strategy.

In November 1904, Lasker launched Lasker's Chess Magazine, which ran until 1909. Starting in 1910, he contributed a weekly chess column for the New York Evening Post, where he served as the Chess Editor.

Emanuel Lasker developed a keen interest in the strategic board game Go after being introduced to it by his namesake, Edward Lasker, likely around 1907 or 1908. He and Edward played Go together while preparing for Lasker's 1908 match with Tarrasch. His interest in Go persisted throughout his life, and he became one of the strongest Go players in Germany and Europe, occasionally contributing to the magazine Deutsche Go-Zeitung. He is famously quoted as saying, "Had I discovered Go sooner, I would probably have never become world chess champion."

At the age of 42, in July 1911, Lasker married Martha Cohn (née Bamberger), a wealthy widow who was a year older than him and already a grandmother. They resided in Berlin. Martha Cohn was also a writer, publishing popular stories under the pseudonym "L. Marco."

1.6. Match against Capablanca and Loss of Title

In January 1920, Lasker and José Raúl Capablanca signed an agreement for a World Championship match to be played in 1921. Due to the delay, Lasker insisted on a clause that allowed him to play any other challenger for the championship in 1920. This clause also stipulated that if Lasker lost a title match in 1920, the contract with Capablanca would be nullified, and if Lasker resigned the title, Capablanca would become World Champion. Lasker had included a similar abdication clause in his pre-World War I agreement to play Akiba Rubinstein for the title.

A report in the American Chess Bulletin (July-August 1920 issue) claimed that Lasker had resigned the world title in favor of Capablanca because the match conditions were unpopular in the chess world. However, the Bulletin speculated that the conditions were not unpopular enough to warrant resignation, suggesting Lasker's true concern was insufficient financial backing to justify dedicating nine months to the match. When Lasker formally resigned the title, he was unaware that chess enthusiasts in Havana had just raised 20.00 K USD to fund the match, provided it was played there. Upon learning of Lasker's resignation, Capablanca traveled to the Netherlands, where Lasker was living, to inform him of Havana's offer. In August 1920, Lasker agreed to play in Havana but insisted that he would be the challenger, as Capablanca was now the champion. Capablanca signed an agreement accepting this point and publicly confirmed it. Lasker also declared that, should he defeat Capablanca, he would resign the title again to allow younger masters to compete for it.

The match commenced in March-April 1921. After four draws, the fifth game saw Lasker make a significant blunder with Black in an otherwise equal ending. Capablanca's solid playing style allowed him to draw the next four games without taking unnecessary risks. In the tenth game, Lasker, playing with White, handled a position with an Isolated Queen Pawn but failed to generate sufficient activity. Capablanca secured a superior ending and duly won. Capablanca also won the eleventh and fourteenth games, leading Lasker to resign the match.

Reuben Fine and Harry Golombek attributed Lasker's defeat to a mysteriously poor form during the match. In contrast, former World Champion Vladimir Kramnik believed that Lasker played quite well and that the match was an "even and fascinating fight" until Lasker's final blunder. Kramnik further suggested that Capablanca, being 20 years younger and having more recent competitive practice, was simply a slightly stronger player at that moment.

1.7. European Life and Travels

After losing the World Championship to Capablanca, Lasker, then in his early 50s, largely retired from serious match play, with his only subsequent match being an unfinished exhibition against Frank James Marshall in 1940. He continued to achieve notable tournament results, winning the Moravská Ostrava 1923 chess tournament (undefeated), the New York 1924 chess tournament (1½ points ahead of Capablanca), and finishing second at Moscow in 1925 (1½ points behind Efim Bogoljubow, ½ point ahead of Capablanca). Following the 1925 Moscow tournament, he effectively retired from elite competitive chess.

During the Moscow 1925 tournament, Lasker received a telegram informing him that the drama written by himself and his brother Berthold Lasker, Vom Menschen die Geschichte ("History of Mankind"), had been accepted for performance at the Lessing theater in Berlin. This news reportedly distracted Lasker, leading to a significant loss against Carlos Torre on the same day. However, the play itself was not a success.

In 1926, Lasker wrote Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, which he re-wrote in English in 1927 as Lasker's Manual of Chess. He also authored books on other games of mental skill, including Encyclopedia of Games (1929) and Das verständige Kartenspiel ("Sensible Card Play"; 1929), both of which introduced problems in the mathematical analysis of card games. His 1931 work, Brettspiele der Völker ("Board Games of the Nations"), featured 30 pages dedicated to Go and a section about Lasca, a game he invented in 1911.

In 1930, Lasker worked as a special correspondent for Dutch and German newspapers, reporting on the Culbertson-Buller bridge match. During this time, he became a registered teacher of the Culbertson system of contract bridge. He developed into an expert bridge player, representing Germany at international events in the early 1930s, and published Das Bridgespiel ("The Game of Bridge") in 1931. In October 1928, Emanuel Lasker's brother Berthold Lasker passed away.

In the spring of 1933, Adolf Hitler's regime initiated a campaign of discrimination and intimidation against Jews, systematically depriving them of their property and citizenship. As both Emanuel Lasker and his wife Martha were Jewish, they were compelled to leave Germany in the same year. After a brief stay in England, they were invited to live in the Soviet Union in 1935 by Nikolai Krylenko, the Commissar of Justice, who was also an enthusiastic supporter of chess. In the USSR, Lasker renounced his German citizenship and acquired Soviet citizenship. He established permanent residence in Moscow and was appointed to a position at Moscow's Institute for Mathematics, as well as serving as a trainer for the USSR national chess team.

Lasker temporarily returned to competitive chess in the Soviet Union to earn money. He finished fifth in Zürich 1934 and achieved a remarkable third place in Moscow 1935, where he was undefeated, finishing only half a point behind Mikhail Botvinnik and Salo Flohr, and notably ahead of Capablanca. His performance in Moscow 1935 at the age of 66 was widely celebrated as "a biological miracle." He continued playing, finishing sixth in Moscow 1936 and tied for seventh in Nottingham 1936.

1.8. Settling in the United States

In August 1937, Martha and Emanuel Lasker decided to leave the Soviet Union, likely due to political upheaval within the country, and moved to the United States in October 1937, first residing in Chicago before settling in New York. In the United States, Lasker, now too old for serious competitive chess, sought to support himself by giving chess and bridge lectures and exhibitions. In 1940, he published his final book, The Community of the Future, in which he proposed solutions for serious political problems, including anti-Semitism and unemployment, demonstrating his lifelong commitment to addressing societal challenges.

2. Assessment

2.1. Playing Strength and Style

Lasker's playing style was often described by his contemporaries as "psychological," implying that he considered his opponent's subjective qualities and mental state in addition to the objective positional demands of the game. Some, like Richard Réti, even suggested that Lasker deliberately played inferior moves to discomfort or confuse his opponents, with W. H. K. Pollock famously commenting, "It is no easy matter to reply correctly to Lasker's bad moves."

However, Lasker himself denied intentionally playing bad moves, and most modern chess commentators and historians agree with him. According to Grandmaster Andrew Soltis and International Master John L. Watson, the characteristics that appeared mysterious to his contemporaries-such as sacrifices for positional advantage, prioritizing "practical" moves over finding the theoretically "best" move, and counterattacking or complicating positions before a disadvantage became critical-are now common in modern chess play. Former World Champion Vladimir Kramnik noted that Lasker "realized that different types of advantage could be interchangeable: tactical edge could be converted into strategic advantage and vice versa," a concept that baffled contemporaries who were still grappling with the codified theories of Steinitz and Tarrasch.

Max Euwe believed that Lasker's success stemmed from his "exceptional defensive technique," stating that "almost all there is to say about defensive chess can be demonstrated by examples from the games of Steinitz and Lasker," with Steinitz representing passive defense and Lasker exemplifying active defense.

Lasker's famous victory against José Raúl Capablanca at St. Petersburg in 1914, a crucial game he needed to win to stay in contention for first place, is often cited as evidence of his "psychological" approach. Reuben Fine described Lasker's choice of opening, the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez, as "innocuous but psychologically potent." Luděk Pachman suggested that Lasker's choice presented Capablanca with a dilemma: needing to play safely with only a half-point lead, but facing an opening whose pawn structure gives White an endgame advantage, forcing Black to use his bishop pair aggressively in the middlegame to neutralize it. However, analysis of Lasker's career shows he had excellent results with this variation as White against strong opponents and often used it in "must-win" situations, leading Kramnik to conclude that his play in this game demonstrated deep positional understanding rather than mere psychology.

While Reuben Fine thought Lasker paid little attention to openings, Capablanca contended that Lasker knew openings exceptionally well but disagreed with much of the contemporary analysis. Indeed, prior to his 1894 World Championship match, Lasker thoroughly studied openings, especially Steinitz's preferred lines. He predominantly favored e4 openings, with the Ruy Lopez being a particular favorite. Although he opened with 1.d4 less frequently, his games starting with 1.d4 had a higher winning percentage. As Black, he typically responded to 1.e4 with the French Defense and to 1.d4 with the Queen's Gambit. He also frequently employed the Sicilian Defense. Capablanca believed that no player surpassed Lasker in the ability to quickly and accurately assess a position, determining who held the better winning prospects and what strategy each side should adopt. Capablanca also noted Lasker's remarkable adaptability, observing that he played in no definite style and was both a tenacious defender and a highly efficient finisher of his own attacks.

Lasker built upon Steinitz's principles, and both demonstrated a profound shift from the earlier "romantic" chess mentality. Thanks to Steinitz and Lasker, positional players became more common, with figures like Tarrasch, Schlechter, and Rubinstein excelling in this style. However, unlike Steinitz, who founded a distinct school of chess thought, Lasker's intuitive and complex talents were much harder for the masses to grasp, thus preventing the formation of a "Lasker school."

Beyond his immense chess skill, Lasker was renowned for his exceptional competitive temperament. His rival, Siegbert Tarrasch, once remarked, "Lasker occasionally loses a game, but he never loses his head." Lasker thrived on the challenge of adapting to diverse playing styles and the fluctuating dynamics of tournaments. Although exceptionally strong in matches, he proved even more formidable in tournaments. For over two decades, he consistently outscored the younger Capablanca, including at St. Petersburg 1914, New York 1924, and Moscow 1925, and Moscow 1935. It was only in 1936, fifteen years after their World Championship match and when Lasker was 67 years old, that Capablanca finally finished ahead of him.

In 1964, Chessworld magazine published an article by future World Champion Bobby Fischer listing the ten greatest players in history. Fischer controversially omitted Lasker, disparaging him as a "coffee-house player [who] knew nothing about openings and didn't understand positional chess." However, in a subsequent poll of leading players, Mikhail Tal, Viktor Korchnoi, and Robert Byrne all named Lasker as the greatest player ever. Both Pal Benko and Byrne later stated that Fischer reconsidered his initial assessment and acknowledged Lasker as a great player.

Statistical ranking systems consistently place Lasker among the greatest players of all time. The book Warriors of the Mind ranks him sixth, behind Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, Fischer, Mikhail Botvinnik, and Capablanca. In his 1978 book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present, Arpad Elo gave retrospective ratings based on players' best five-year spans, concluding that Lasker was the joint second strongest player surveyed (tied with Botvinnik and behind Capablanca). The Chessmetrics system, sensitive to comparison periods, ranks Lasker between fifth and second strongest of all time for peak periods ranging from one to twenty years. Its author, statistician Jeff Sonas, concluded that only Kasparov and Karpov surpassed Lasker's long-term dominance of the game. According to Chessmetrics, Lasker held the number one ranking for 292 different months, totaling over 24 years, with his first No. 1 rank in June 1890 and his last in December 1926, spanning 36½ years. Chessmetrics also identifies him as the strongest 67-year-old in history: in December 1935, his rating was 2691 (ranking 7th in the world), significantly higher than the next best 67-year-old, Viktor Korchnoi, who had a rating of 2660 (ranking 39th) in March 1998.

2.2. Influence on Chess

Lasker did not establish a specific school of players who adopted his exact playing style. As Max Euwe noted, "It is not possible to learn much from him. One can only stand and wonder." However, Lasker's pragmatic and combative approach significantly influenced Soviet players such as Mikhail Tal and Viktor Korchnoi.

Several "Lasker Variations" exist in chess openings, including Lasker's Defense to the Queen's Gambit, Lasker's Defense to the Evans Gambit (which effectively ended the use of this gambit in tournament play for decades until its revival in the 1990s), and the Lasker Variation in the McCutcheon Variation of the French Defense.

Deeply affected by the poverty in which Wilhelm Steinitz died, Lasker was determined not to face a similar fate. He became known for demanding high fees for playing in matches and tournaments. Furthermore, he argued that players, not just publishers, should own the copyright to their games, thereby retaining a share of the profits. Initially, these demands caused friction with editors and other players. However, they were instrumental in paving the way for the emergence of full-time chess professionals who derive their livelihoods primarily from playing, writing, and teaching chess. The issue of copyright in chess games had been contentious since at least the mid-1840s, with both Steinitz and Lasker vigorously asserting players' rights and incorporating copyright clauses into their match contracts.

Despite its benefits for professional chess, Lasker's insistence on substantial purses for championship matches sometimes prevented or delayed eagerly anticipated contests. For example, Frank James Marshall challenged him for the World Championship in 1904 but could not meet Lasker's financial demands until 1907. This problem persisted through the reign of Lasker's successor, Capablanca. Recognizing the issues caused by these controversial match conditions, Capablanca twice attempted (in 1914 and 1922) to establish a standardized set of rules for World Championship matches, which were readily accepted by other top players.

2.3. Work in Other Fields

In his seminal 1905 article on commutative algebra, Lasker introduced the groundbreaking theory of primary decomposition of ideals. This work proved influential in the theory of Noetherian rings, and rings possessing the primary decomposition property are named "Laskerian rings" in his honor.

Lasker's early attempts to create a general theory of all competitive activities, as outlined in his book Kampf, laid conceptual groundwork for later, more systematic efforts in game theory, notably by John von Neumann. His subsequent writings on card games also presented significant challenges in the mathematical analysis of card games. According to R. J. Nowakowski, Lasker "came close to a complete theory of impartial games."

However, despite his intellectual breadth, Lasker's dramatic and philosophical works never achieved widespread recognition or critical acclaim.

3. Personal Life and Family

Lasker's personal life was intertwined with his intellectual pursuits and close relationships. He was survived by his wife, Martha Cohn, and his sister, Mrs. Lotta Hirschberg. His sister-in-law was the renowned poet Else Lasker-Schüler, who was married to his brother Berthold.

Edward Lasker, a German-American chess master, engineer, and author born in Kempen (Kępno), claimed a distant relation to Emanuel Lasker. Both played in the prestigious New York 1924 chess tournament, where Edward noted that Emanuel informed him shortly before his death about a family tree showing their connection.

Emanuel Lasker was a close friend of Albert Einstein, who penned the introduction to the posthumous biography Emanuel Lasker, The Life of a Chess Master by Dr. Jacques Hannak (1952). In this preface, Einstein expressed his deep admiration for Lasker, writing that Lasker was "undoubtedly one of the most interesting people I came to know in my later years." He added, "We must be thankful to those who have penned the story of his life for this and succeeding generations. For there are few men who have had a warm interest in all the great human problems and at the same time kept their personality so uniquely independent."

4. Death

Emanuel Lasker died on January 11, 1941, in New York, at the age of 72, due to a kidney infection. He was admitted as a charity patient at the Mount Sinai Hospital. His funeral service was held at the Riverside Memorial Chapel, and he was subsequently buried at the historic Beth Olam Cemetery in Queens, New York.

5. Publications

Emanuel Lasker was a prolific writer, contributing extensively to the fields of chess, other games, mathematics, and philosophy.

5.1. Chess Publications

- The London Chess Fortnightly, 1892-93

- Common Sense in Chess, 1896 (an abstract of 12 lectures delivered in London in 1895)

- Lasker's How to Play Chess: An Elementary Text Book for Beginners, Which Teaches Chess By a New, Easy and Comprehensive Method, 1900

- Lasker's Chess Magazine, 1904-1907

- The International Chess Congress, St. Petersburg, 1909, 1910

- Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, 1926

- Lasker's Manual of Chess, 1925 (English version published in 1927), noted for its philosophical tone as much as its chess content

- Lasker's Chess Primer, 1934

5.2. Publications on Other Games

- Encyclopedia of Games Vol. I, Card Strategy, New York 1929

- Das verständige Kartenspiel (Sensible Card Play), Berlin 1929 (English translation in the same year)

- Brettspiele der Völker (Board Games of the Nations), Berlin 1931 (includes sections on Go and Lasca)

- Das Bridgespiel ("The Game of Bridge"), 1931

5.3. Mathematical Publications

- "Metrical Relations of Plane Spaces of n Manifoldness," Nature, August 1895

- "About a certain Class of Curved Lines in Space of n Manifoldness," Nature, October 1895

- Über Reihen auf der Convergenzgrenze ("On Series at Convergence Boundaries"), Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 1901 (Lasker's PhD thesis)

- "Zur Theorie der Moduln und Ideale," Math. Ann., 1905

5.4. Philosophical Publications

- Kampf (Struggle), 1906

- Das Begreifen der Welt (Comprehending the World), 1913

- Die Philosophie des Unvollendbar (The Philosophy of the Unattainable), 1918

- Vom Menschen die Geschichte ("History of Mankind"), 1925 (a play, co-written with his brother Berthold Lasker)

- The Community of the Future, 1940

6. Tournament and Match Results

The following tables summarize Emanuel Lasker's major chess tournament and match results. In the "Score" columns, the first value indicates the total points obtained out of the maximum possible. In the second "Score" column, "+" denotes the number of won games, "-" indicates losses, and "=" denotes draws.

| Date | Location | Place | Total Score | Game Score | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1888/89 | Berlin (Café Kaiserhof) | 1st | 20/20 | +20-0=0 | |

| 1889 | Breslau "B" | 1st = | 12/15 | +11-2=2 | Tied with von Feyerfeil and won the play-off. This was Hauptturnier A of the sixth DSB Congress, i.e. the "second-division" tournament. |

| 1889 | Amsterdam "A" tournament | 2nd | 6/8 | +5-1=2 | Behind Amos Burn; ahead of James Mason, Isidor Gunsberg and others. This was the stronger of the two Amsterdam tournaments held at that time. |

| 1890 | Berlin | 1-2 | 6½/8 | +6-1=1 | Tied with his brother Berthold Lasker. |

| 1890 | Graz | 3rd | 4/6 | +3-1=2 | Behind Gyula Makovetz and Johann Hermann Bauer. |

| 1892 | London | 1st | 9/11 | +8-1=2 | Ahead of Mason and Rudolf Loman. |

| 1892 | London | 1st | 6½/8 | +5-0=3 | Ahead of Joseph Henry Blackburne, Mason, Gunsberg and Henry Edward Bird. |

| 1893 | New York City | 1st | 13/13 | +13-0=0 | Ahead of Adolf Albin, Jackson Showalter and a newcomer named Harry Nelson Pillsbury. |

| 1895 | Hastings | 3rd | 15½/21 | +14-4=3 | Behind Pillsbury and Mikhail Chigorin; ahead of Siegbert Tarrasch, Wilhelm Steinitz and the rest of a strong field. |

| 1895/96 | St. Petersburg | 1st | 11½/18 | +8-3=7 | A Quadrangular tournament; ahead of Steinitz (by two points), Pillsbury and Chigorin. |

| 1896 | Nuremberg | 1st | 13½/18 | +12-3=3 | Ahead of Géza Maróczy, Pillsbury, Tarrasch, Dawid Janowski, Steinitz and the rest of a strong field. |

| 1899 | London | 1st | 23½/28 | +20-1=7 | Ahead of Janowski, Pillsbury, Maróczy, Carl Schlechter, Blackburne, Chigorin and several other strong players. |

| 1900 | Paris | 1st | 14½/16 | +14-1=1 | Ahead of Pillsbury (by two points), Frank James Marshall, Maróczy, Burn, Chigorin and several others. |

| 1904 | Cambridge Springs | 2nd = | 11/15 | +9-2=4 | Tied with Janowski; two points behind Marshall; ahead of Georg Marco, Showalter, Schlechter, Chigorin, Jacques Mieses, Pillsbury and others. |

| 1906 | Trenton Falls | 1st | 5/6 | +4-0=2 | A Quadrangular tournament; ahead of Curt, Albert Fox and Raubitschek. |

| 1909 | St. Petersburg | 1st = | 14½/18 | +13-2=3 | Tied with Akiba Rubinstein; ahead of Oldřich Duras and Rudolf Spielmann (by 3½ points), Ossip Bernstein, Richard Teichmann and several other strong players. |

| 1914 | St. Petersburg | 1st | 13½/18 | +10-1=7 | Ahead of José Raúl Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall. This tournament had an unusual structure: there was a preliminary tournament in which eleven players played each other player once; the top five players then played a separate final tournament in which each player who made the "cut" played the other finalists twice; but their scores from the preliminary tournament were carried forward. Even the preliminary tournament would now be considered a "super-tournament". Capablanca "won" the preliminary tournament by 1½ points without losing a game, but Lasker achieved a plus score against all his opponents in the final tournament and finished with a combined score ½ point ahead of Capablanca's. |

| 1918 | Berlin | 1st | 4½/6 | +3-0=3 | Quadrangular tournament. Ahead of Rubinstein, Schlechter and Tarrasch. |

| 1923 | Moravská Ostrava | 1st | 10½/13 | +8-0=5 | Ahead of Richard Réti, Ernst Grünfeld, Alexey Selezniev, Savielly Tartakower, Max Euwe and other strong players. |

| 1924 | New York City | 1st | 16/20 | +13-1=6 | Ahead of Capablanca (by 1½ points), Alekhine, Marshall, and the rest of a very strong field. |

| 1925 | Moscow | 2nd | 14/20 | +10-2=8 | Behind Efim Bogoljubow; ahead of Capablanca, Marshall, Tartakower, Carlos Torre, other strong non-Soviet players and the leading Soviet players. |

| 1934 | Zürich | 5th | 10/15 | +9-4=2 | Behind Alekhine, Euwe, Salo Flohr and Bogoljubow; ahead of Bernstein, Aron Nimzowitsch, Gideon Ståhlberg and various others. |

| 1935 | Moscow | 3rd | 12½/19 | +6-0=13 | Half a point behind Mikhail Botvinnik and Flohr; ahead of Capablanca, Spielmann, Ilya Kan, Grigory Levenfish, Andor Lilienthal, Viacheslav Ragozin and others. Emanuel Lasker was about 67 years old at the time. |

| 1936 | Moscow | 6th | 8/18 | +3-5=10 | Capablanca won. |

| 1936 | Nottingham | 7-8th | 8½/14 | +6-3=5 | Capablanca and Botvinnik tied for first place. |

| Date | Opponent | Result | Location | Total Score | Game Score | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | E.R. von Feyerfeil | Won | Breslau | 1-0 | +1-0=0 | Play-off match |

| 1889/90 | Curt von Bardeleben | Won | Berlin | 2½-1½ | +2-1=1 | |

| 1889/90 | Jacques Mieses | Won | Leipzig | 6½-1½ | +5-0=3 | |

| 1890 | Berthold Lasker | Drew | Berlin | ½-½ | +0-0=1 | Play-off match |

| 1890 | Henry Edward Bird | Won | Liverpool | 8½-3½ | +7-2=3 | |

| 1890 | N.T. Miniati | Won | Manchester | 4-1 | +3-0=2 | |

| 1890 | Berthold Englisch | Won | Vienna | 3½-1½ | +2-0=3 | |

| 1891 | Francis Joseph Lee | Won | London | 1½-½ | +1-0=1 | |

| 1892 | Joseph Henry Blackburne | Won | London | 8-2 | +6-0=4 | |

| 1892 | Bird | Won | Newcastle upon Tyne | 5-0 | +5-0=0 | |

| 1892/93 | Jackson Showalter | Won | Logansport and Kokomo, Indiana | 7-3 | +6-2=2 | |

| 1893 | Celso Golmayo Zúpide | Won | Havana | 2½-½ | +2-0=1 | |

| 1893 | Andrés Clemente Vázquez | Won | Havana | 3-0 | +3-0=0 | |

| 1893 | A. Ponce | Won | Havana | 2-0 | +2-0=0 | |

| 1893 | Alfred Ettlinger | Won | New York City | 5-0 | +5-0=0 | |

| 1894 | Wilhelm Steinitz | Won | New York, Philadelphia, Montreal | 12-7 | +10-5=4 | Won World Chess Championship |

| 1896/97 | Steinitz | Won | Moscow | 12½-4½ | +10-2=5 | Retained World Chess Championship |

| 1901 | Dawid Janowski | Won | Manchester | 1½-½ | +1-0=1 | |

| 1903 | Mikhail Chigorin | Lost | Brighton | 2½-3½ | +1-2=3 | Rice Gambit-themed match |

| 1907 | Frank James Marshall | Won | New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Chicago, Memphis | 11½-3½ | +8-0=7 | Retained World Chess Championship |

| 1908 | Siegbert Tarrasch | Won | Düsseldorf, Munich | 10½-5½ | +8-3=5 | Retained World Chess Championship |

| 1908 | Abraham Speijer | Won | Amsterdam | 2½-½ | +2-0=1 | |

| 1909 | Janowski | Drew | Paris | 2-2 | +2-2=0 | Exhibition match |

| 1909 | Janowski | Won | Paris | 8-2 | +7-1=2 | |

| 1910 | Carl Schlechter | Drew | Vienna-Berlin | 5-5 | +1-1=8 | Retained World Chess Championship |

| 1910 | Janowski | Won | Berlin | 9½-1½ | +8-0=3 | Retained World Chess Championship |

| 1914 | Ossip Bernstein | Drew | Moscow | 1-1 | +1-1=0 | Exhibition match |

| 1916 | Tarrasch | Won | Berlin | 5½-½ | +5-0=1 | |

| 1921 | José Raúl Capablanca | Lost | Havana | 5-9 | +0-4=10 | Lost World Chess Championship |

| 1940 | Frank James Marshall | Unfinished due to Lasker's illness and death | New York | ½-1½ | +0-1=1 | Exhibition match |

7. Notable Games

Several games from Emanuel Lasker's career are considered particularly significant for their tactical or strategic depth and have been extensively analyzed by chess experts.

- Lasker vs. Johann Hermann Bauer, Amsterdam 1889. While not the earliest instance of a successful two-bishops sacrifice, this combination is famously known as a "Lasker-Bauer combination" or "Lasker sacrifice."

- Harry Nelson Pillsbury vs. Lasker, St. Petersburg 1895. A brilliant sacrifice on the 17th move initiates a decisive attack leading to victory for Lasker.

- Wilhelm Steinitz vs. Lasker, London 1899. This game features a fierce struggle between the old champion and the new one.

- Frank James Marshall vs. Lasker, World Championship Match 1907, game 1. Lasker's initial attack proves insufficient for a quick win, so he expertly transitions into an endgame where he swiftly outmaneuvers Marshall.

- Lasker vs. Carl Schlechter, match 1910, game 10. While not a masterpiece of chess, this game is notable because it was the one that allowed Lasker to save his world title in 1910, preventing Schlechter from clinching the championship.

- Lasker vs. Jose Raul Capablanca, St. Petersburg 1914. In a game he crucially needed to win, Lasker unexpectedly opted for a quiet opening, allowing Capablanca to simplify the game early. This game has been the subject of much debate regarding whether Lasker's approach was a subtle psychological maneuver or a display of deep positional understanding.

- Max Euwe vs. Lasker, Zurich 1934. At 66 years old, Lasker defeated a future World Champion in this game, famously sacrificing his queen to transform a defensive position into a winning attack.

8. In Popular Culture

Emanuel Lasker's enduring legacy has occasionally found its way into popular culture. In Michael Chabon's alternate history mystery novel, The Yiddish Policemen's Union, a murdered character named Mendel Shpilman (born in the 1960s), who is an avid chess enthusiast, uses "Emanuel Lasker" as an alias. This reference is immediately recognized by the protagonist, Detective Meyer Landsman, who also possesses a knowledge of chess.