1. Overview

Elgin Gay Baylor was an American professional basketball player, coach, and executive who profoundly influenced the sport. He played 14 seasons as a forward for the Minneapolis/Los Angeles Lakers in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Renowned for his exceptional athleticism, innovative playing style, and trademark hanging jump shot, Baylor was a gifted shooter, a strong rebounder, and an accomplished passer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest players in basketball history, pioneering an acrobatic style that transformed the game and inspired future generations of superstars like Julius Erving and Michael Jordan.

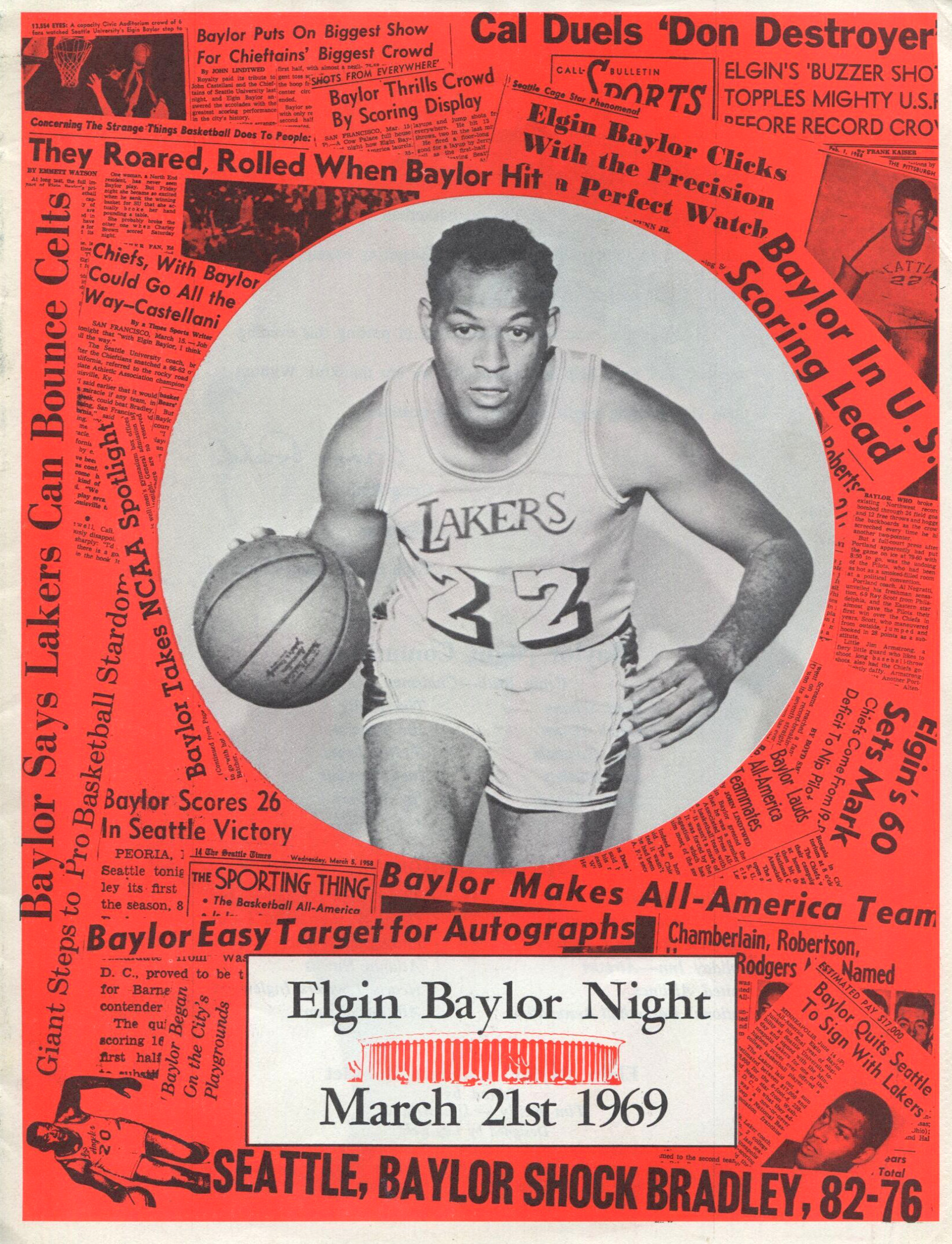

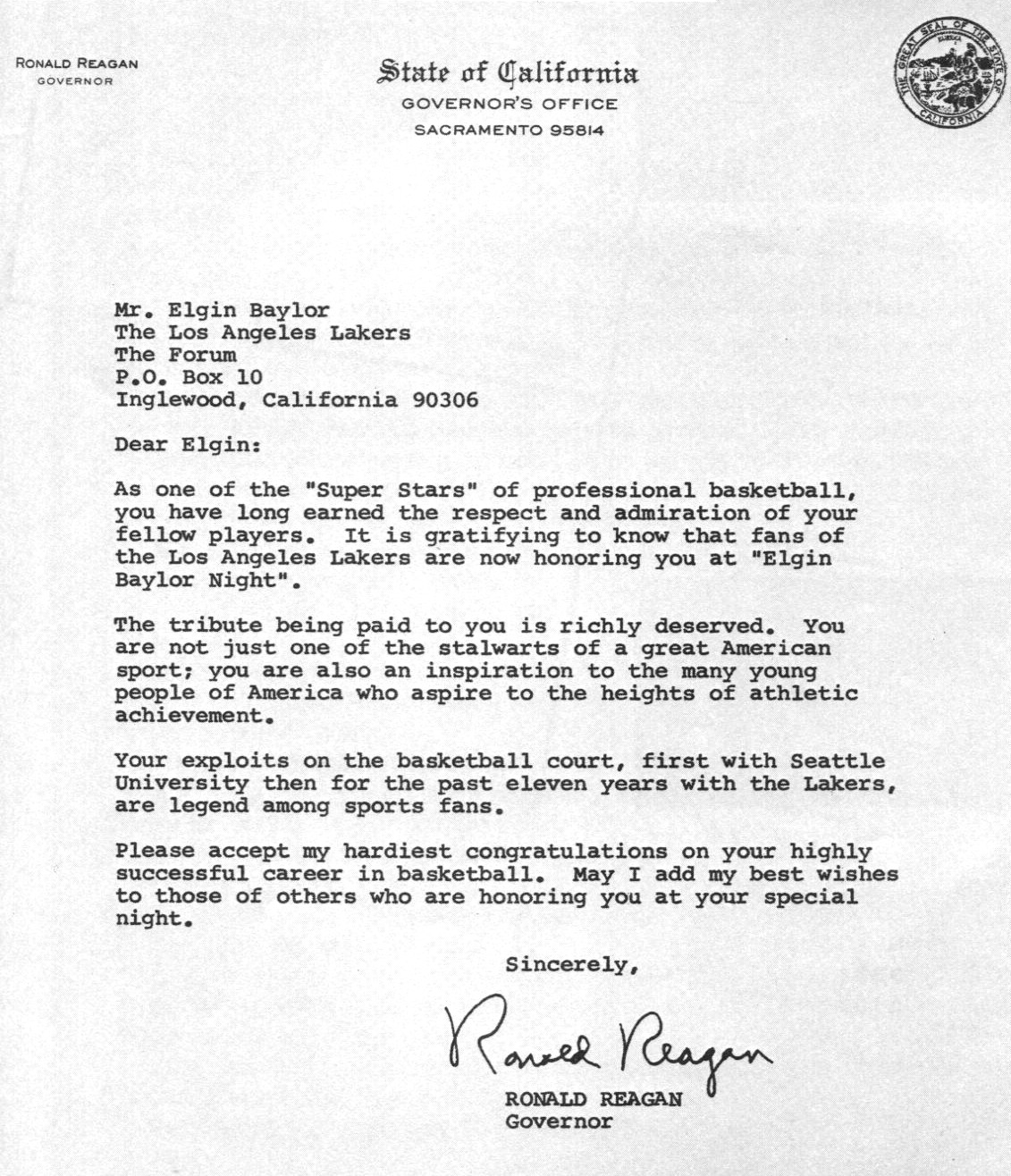

A No. 1 draft pick in 1958, Baylor earned the NBA Rookie of the Year award in 1959, was an 11-time NBA All-Star, and a 10-time member of the All-NBA First Team. He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1977 and was named to the NBA's 35th, 50th, and 75th Anniversary Teams. His No. 22 jersey is retired by the Lakers. After his playing career, Baylor served as a head coach for the New Orleans Jazz and later spent 22 years as the Vice President of Basketball Operations for the Los Angeles Clippers, earning the NBA Executive of the Year Award in 2006.

2. Early life and education

Elgin Baylor's early life was shaped by the challenges of racial segregation in Washington D.C., which limited his access to basketball facilities. Despite these obstacles, he developed into a standout high school player, setting scoring records and earning accolades that foreshadowed his professional success.

2.1. Childhood and high school

Elgin Gay Baylor was born in Washington, D.C., on September 16, 1934, to Uzziel (Lewis) and John Wesley Baylor. He began playing basketball at the age of 14. Growing up near a D.C. city recreation center, Baylor faced significant limitations as African Americans were banned from using the facilities, restricting his access to basketball courts. His two brothers, Sal and Kermit, also played basketball.

Baylor played his first two years of high school basketball at Phelps Vocational High School during the 1951 and 1952 seasons. At the time, public schools in Washington, D.C., were segregated, meaning he only competed against other black high school teams. While at Phelps, Baylor set an area scoring record of 44 points against Cardozo High School. During his two All-City years at Phelps, he averaged 18.5 and 27.6 points per season. However, he struggled academically and dropped out of school in 1952-53 to work in a furniture store and play basketball in local recreational leagues.

Baylor returned to high school basketball for the 1954 season as a senior, playing for the recently opened all-black Spingarn High School. Standing 6 in and weighing 225 lb (225 lb), he was named first-team Washington All-Metropolitan, becoming the first African-American player to receive that honor. Baylor also won the SSA's Livingstone Trophy as the area's best basketball player for 1954. He finished the season with an impressive 36.1 point average in his eight Interhigh Division II league games. On February 3, 1954, in a game against his former team, Phelps, Baylor scored 31 points in the first half. Despite playing the entire second half with four fouls, he added 32 more points to set a new D.C.-area record of 63 points. This broke the previous record of 52 points set by Jim Wexler the year before, which had itself broken Baylor's earlier record of 44 points. However, because Wexler was white and Baylor was black, Baylor's record did not receive the same media coverage, including from The Washington Post, as Wexler's.

3. College career

Despite his high school success, Baylor faced challenges in college recruitment due to academic qualifications and the prevalent racial segregation that deterred college scouts from recruiting at black high schools. His collegiate journey ultimately led him to become a dominant force in the NCAA, culminating in a national championship appearance.

3.1. College of Idaho

Although some colleges were willing to accept Baylor, he did not qualify academically for major programs. A friend of Baylor's who attended the College of Idaho helped arrange a football scholarship for him for the 1954-55 academic year. Baylor never played football for the school; instead, he was accepted onto the college's basketball team without needing to try out. He quickly distinguished himself, outperforming other players on the team that season by averaging over 31 points and 20 rebounds per game.

After that season, the College of Idaho dismissed its head basketball coach and restricted its athletic scholarships. This led Baylor to seek other opportunities.

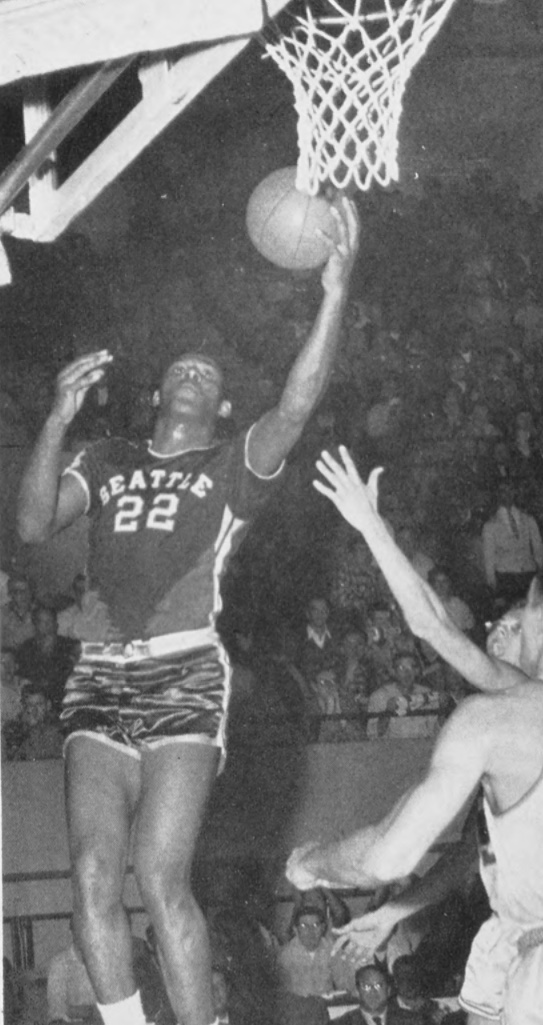

3.2. Seattle University

A car dealer in Seattle interested Baylor in Seattle University. Baylor sat out a year to play for Westside Ford, an Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) team in Seattle, while establishing his eligibility at Seattle University. The Minneapolis Lakers drafted him in the 14th round of the 1956 NBA draft, but Baylor opted to remain in school.

During the 1956-57 season, Baylor averaged 29.7 points and 20.3 rebounds per game for Seattle. The following season, he averaged 32.5 points per game and led the Seattle University Chieftains (now known as the Redhawks) to the NCAA championship game. This marked Seattle's only trip to the Final Four, where they ultimately fell to the Kentucky Wildcats with a score of 72-84. Following his junior season, Baylor was drafted again by the Minneapolis Lakers, this time with the No. 1 overall pick in the 1958 NBA draft. He decided to leave school to join them for the 1958-59 NBA season.

Over his three collegiate seasons-one at the College of Idaho and two at Seattle University-Baylor averaged 31.3 points and 19.5 rebounds per game. He led the NCAA in rebounds during the 1956-57 season.

4. Professional career

Elgin Baylor's professional career with the Lakers spanned 14 seasons, during which he established himself as a revolutionary player, overcoming injuries and military service to achieve individual greatness, though a championship eluded him until his retirement.

4.1. Minneapolis / Los Angeles Lakers (1958-1971)

Baylor's tenure with the Lakers began in Minneapolis and continued after the team's move to Los Angeles, where he became a franchise cornerstone, leading the team through multiple NBA Finals appearances.

4.1.1. Rookie season and saving the franchise

The Minneapolis Lakers used the No. 1 overall pick in the 1958 NBA draft to select Baylor, convincing him to forgo his senior year at Seattle University and join the professional ranks. The team had been struggling significantly since the retirement of its star center George Mikan in 1954. The year before Baylor's arrival, the Lakers finished with a dismal 19-53 record, the worst in the league, with a slow, bulky, and aging squad. The franchise also lacked a permanent home arena, was losing popularity, and faced severe financial trouble. Owner Bob Short, who was on the verge of selling the team, believed Baylor's exceptional athletic talents and all-around game could save the franchise. Short famously told the Los Angeles Times in a 1971 interview, "If he had turned me down then, I would have been out of business. The club would have gone bankrupt." Baylor signed with the Lakers for 20.00 K USD per year, a substantial sum in the NBA at the time. According to basketball historian James Fisher, Baylor, by virtue of his exceptional skills and central role in the team's business plan, became the NBA's first true franchise player.

Baylor immediately exceeded expectations and played a crucial role in revitalizing the Lakers franchise. As a rookie in 1958-59, he finished fourth in the league in scoring with 24.9 points per game, third in rebounding with 15.0 rebounds per game, and eighth in assists with 4.1 assists per game. He scored 55 points in a single game, which was then the third-highest mark in league history, behind Joe Fulks' 63 and Mikan's 61.

On January 16, 1959, Baylor took a principled stand against racial discrimination. He refused to play in a road game in Charleston, West Virginia, after the hotel the team had booked denied lodging to the team's three black players, Baylor, Bo Ellis, and Ed Fleming. When a teammate attempted to persuade him to play, Baylor responded, "I'm a human being, I'm not an animal put in a cage and let out for the show." Days later, the mayor of Charleston apologized to Baylor. Two years later, Baylor returned to Charleston for the All-Star Game, staying at the hotel that had previously refused him and eating at the restaurant that had denied him entry, underscoring his unwavering commitment to human dignity.

Baylor won the NBA Rookie of the Year Award and led the Lakers to the NBA Finals, where they lost to the Boston Celtics in the first four-game sweep in finals history. This defeat marked the beginning of what would become the greatest rivalry in NBA history between the Lakers and Celtics. Baylor's presence helped the Lakers improve their record significantly, from 19-53 to 33-39.

4.1.2. Peak years and record-breaking

In 1960, the Lakers moved from Minneapolis to Los Angeles, becoming the first NBA team on the West Coast. This relocation was crucial for the league's national expansion. To further bolster the team, the Lakers drafted Jerry West as their No. 2 overall pick in the 1960 NBA draft to play point guard, and hired Fred Schaus, who had also coached West during his college career. The dynamic duo of Baylor and West, later joined in 1968 by center Wilt Chamberlain, propelled the Lakers to consistent success in the Western Division throughout the 1960s.

From the 1960-61 to the 1962-63 seasons, Baylor averaged an astounding 34.8, 38.3, and 34.0 points per game, respectively. On November 15 of the 1960-61 season, Baylor set an NBA scoring record when he scored 71 points in a victory against the New York Knicks, while also grabbing 25 rebounds. In doing so, Baylor became the first NBA player to score more than 70 points in a game, breaking his own NBA record of 64 points that he had set the previous November. Baylor held the record until 1962, when Chamberlain scored 100 points. Knicks player Richie Guerin later commented that Baylor's 71-point performance was "far better" than Chamberlain's 100, noting that Baylor achieved his points "naturally" while Chamberlain's teammates were actively trying to set him up for the record. The Lakers' move to Los Angeles, coupled with Baylor's and West's stellar play, quickly captivated the city, with celebrities frequently seen courtside.

Baylor, a United States Army Reservist, was called to active duty during the 1961-62 NBA season. Stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington, he could play for the Lakers only when on a weekend pass. This meant he was unable to practice with the team before or during the season and had to fly coach across the country on weekends to join the team. Despite playing only 48 games that season, he still managed to score over 1,800 points, averaging a career-high 38.3 points (the highest average in NBA history by any player other than Chamberlain), 18.6 rebounds, and 4.6 assists per game. Later that season, in a Game Five NBA Finals victory against the Boston Celtics, Baylor set the still-standing NBA record for points in an NBA Finals game with 61. Basketball historian James Fisher described Baylor's performance that season as: "Not bad for a part-time job." Baylor himself later said he "kind of enjoyed that season."

4.1.3. Military service and impact of injuries

Baylor's career was significantly impacted by his military service and a series of severe knee injuries. His call to active duty in the Army Reserve during the 1961-62 season meant he could only play for the Lakers on weekend passes, severely limiting his availability and practice time. Despite this, he achieved remarkable individual statistics, including his career-high 38.3 points per game.

His physical challenges deepened when he suffered a severe knee injury during the opening game of the 1965 Western Division playoffs against the Baltimore Bullets. Baylor distinctly recalled hearing his left knee ligament tear. The injury required surgery and forced him to miss the remainder of the playoffs. Although he managed to score more than 24 points in each of the next four seasons despite his injury, the limitations of knee surgery at the time and the lack of comprehensive rehabilitation left him with persistent knee problems. These issues ultimately necessitated surgery on both knees, severely impairing his playing ability for the rest of his career. Doctors initially believed his basketball career was over. Despite regaining about "75% of his peak mobility," Baylor's once-acrobatic style was hampered.

He played just two games in the 1970-71 NBA season before rupturing his Achilles tendon, an injury that effectively ended his ability to perform at an elite level.

4.1.4. Retirement and championship irony

Due to his persistent and debilitating injuries, Baylor finally retired nine games into the 1971-72 NBA season. He announced his retirement at a press conference on November 4, 1971, stating that he could no longer play at the highest level of the sport and wanted to free up a roster spot for other players on the Lakers. His last game was a 105-109 loss to the Golden State Warriors on October 31, 1971.

In his 14 seasons as the Lakers' forward, Baylor helped lead the team to the NBA Finals eight times, but the team lost each time, often to their arch-rivals, the Boston Celtics. The timing of his retirement proved to be a poignant irony: the Lakers' first game after his departure, on November 5, 1971, marked the beginning of an NBA-record 33-game win streak. This historic run culminated in the Lakers winning the 1972 NBA championship, their first in Los Angeles. Many teammates and observers believed Baylor's retirement, after years of carrying the franchise, galvanized the team and fostered a new level of unity, ultimately leading to their long-awaited championship. Despite not playing in the championship season, Baylor was given a championship ring by the Lakers for his significant contributions to the franchise. He is often listed as the greatest NBA player never to win a championship.

4.2. Player characteristics and playing style

Baylor was renowned as an all-around player, excelling in every facet of the game, including offense, defense, rebounding, and passing. Standing 6 in, he was considered short for a forward even during his era. However, he compensated with immense strength, allowing him to "muscle through" defenders, and an unparalleled finesse and creativity to maneuver around them, frequently securing second-chance points from missed shots.

Baylor was particularly celebrated for his superior leaping abilities, which enabled him to score by staying airborne longer than his defenders. Bill Russell famously called him "the godfather of hang time." He innovated various "moves" to deceive opponents, often involving changing hands or direction mid-air. His offensive repertoire included a running bank shot and a left-handed hook shot, despite being right-handed. He also utilized an on-court facial twitch as a deceptive head fake. Baylor attributed his success to a natural talent for jumping and the ability to spontaneously react to defensive plays.

Before Baylor joined the NBA in 1958, the league's play was often described as methodical and mechanical, dominated by set jump shots and running hook shots. Baylor introduced a creative and acrobatic playing style that fundamentally transformed the game. His ability to elevate and maneuver in the air, seemingly defying gravity, ushered in an era of "vertical" basketball, moving the sport beyond its previous "horizontal" confines, as noted by Bill Simmons. His innovative approach and aerial artistry significantly influenced later NBA superstars such as Connie Hawkins, Julius Erving, and Michael Jordan. His contemporaries held him in high regard: Oscar Robertson described Baylor as "the first and original high flier," Bill Sharman called him "the greatest cornerman who ever played pro basketball," and Tom Heinsohn stated, "Baylor as forward beats out Bird, Julius Erving and everybody else." Tommy Hawkins summarized his impact by saying, "Pound-for-pound, no one was greater than Elgin Baylor." The Basketball Hall of Fame itself referred to Baylor as "Unstoppable."

Baylor was also an underrated rebounder, averaging 13.5 rebounds per game over his career. His remarkable 19.8 rebounds per game during the 1960-61 season was a feat exceeded by only five other players in NBA history, all of whom were 6 in or taller, making his achievement particularly notable for his size.

5. Coaching career

After his illustrious playing career, Baylor transitioned into coaching, though his tenure was less successful than his time on the court.

In 1974, Baylor was hired as an assistant coach for the New Orleans Jazz. He briefly served as an interim head coach for one game following the dismissal of Scotty Robertson, before Butch van Breda Kolff took over. Baylor officially became the head coach from the 1976-77 season until the 1978-79 season. During his time with the Jazz, he coached star player Pete Maravich. However, Baylor had a lackluster coaching record of 86 wins and 135 losses, with a win percentage of .389, and never led the Jazz to the playoffs. He was fired shortly before the team relocated to Salt Lake City, Utah.

6. Executive career

Baylor's longest post-playing career role was as a basketball executive, where he spent over two decades with the Los Angeles Clippers, navigating the team through challenging periods and achieving recognition for his management.

6.1. Los Angeles Clippers

In 1986, Baylor was hired by the Los Angeles Clippers as the team's Vice President of Basketball Operations. He held this position for 22 years, until October 2008, managing the team for the majority of the Donald Sterling ownership period. During his long tenure, Baylor was instrumental in building the team around key players such as Danny Manning in the 1990s and Elton Brand in the 2000s.

Despite his efforts, the Clippers achieved only two winning seasons under his leadership and amassed a win-loss record of 607-1153. They made the playoffs only four times and won just one playoff series during this period. However, Baylor's contributions were recognized in 2006 when he was selected as the NBA Executive of the Year. He was relieved of his executive duties in October 2008, shortly before the start of the 2008-09 season, at the age of 74.

In February 2009, Baylor filed an employment discrimination lawsuit against the Clippers, team owner Donald Sterling, team president Andy Roeser, and the NBA. He alleged that he was underpaid during his tenure with the team and then fired because of his age and race. Baylor later dropped the racial discrimination claims from the suit. In 2011, a jury decided in the Clippers' favor on Baylor's remaining claims, finding that his termination was based on the team's poor performance. However, Baylor stated he felt vindicated when Donald Sterling was banned for life from the NBA in 2014 after recordings of him making racist comments were publicized by the press.

7. Later life and death

After his extensive careers in basketball, Baylor continued to be a public figure, making television appearances and engaging in other activities. His passing in 2021 prompted widespread tributes from across the basketball world.

Baylor's popularity extended beyond the basketball court, leading to appearances on various television series. He was featured on Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In in 1968, appeared in The Jackson 5's first TV special in 1971, had a role in an episode of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century titled "Olympiad," and was seen in an episode of The White Shadow called "If Your Number's Up, Get Down." In 1974, he also volunteered to play a mixed doubles exhibition tennis match with Tracy Austin against Lawrence McCutcheon and Lea Antonopolis in Claremont, California, for a sold-out crowd.

Elgin Baylor died in a Los Angeles hospital of natural causes on March 22, 2021, at the age of 86. He was surrounded by his wife, Elaine, and their daughter, Krystle, as well as two children from a previous marriage, Alan and Alison, and his sister, Gladys. He is interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills).

8. Legacy and impact

Elgin Baylor's enduring influence on basketball is profound, marked by his revolutionary playing style, numerous accolades, and his stand against discrimination. His contributions transformed the game and continue to inspire.

8.1. Revolutionizing basketball play

Since the beginning of his NBA career, Baylor has been considered one of the best basketball players in the world, and his reputation as one of the greatest in history has endured. Before Baylor joined the NBA in 1958, the league's play was often described as methodical and mechanical, dominated by set jump shots and running hook shots. Baylor introduced a creative and acrobatic playing style that fundamentally transformed the way basketball was played. His ability to elevate and maneuver in the air, seemingly defying gravity, ushered in an era of "vertical" basketball, moving the sport beyond its previous "horizontal" confines, as noted by Bill Simmons, who wrote, "Along with Russell, Elgin turned a horizontal game into a vertical one."

His innovative approach and aerial artistry significantly influenced later NBA superstars such as Connie Hawkins, Julius Erving, and Michael Jordan. His contemporaries held him in high regard: Oscar Robertson described Baylor as "the first and original high flier," Bill Sharman called Baylor "the greatest cornerman who ever played pro basketball," and Tom Heinsohn stated, "Baylor as forward beats out Bird, Julius Erving and everybody else." Tommy Hawkins summarized his impact by saying, "Pound-for-pound, no one was greater than Elgin Baylor." The Basketball Hall of Fame itself referred to Baylor as "Unstoppable."

Baylor was the last of the great undersized forwards in a league where many guards are now his size or bigger. He finished his playing days with 23,149 points, 3,650 assists, and 11,463 rebounds over 846 games. His signature running bank shot, which he was able to release quickly and effectively over taller players, led him to numerous NBA scoring records, several of which still stand. The 71 points Baylor scored on November 15, 1960, was a record at the time; it was also a team record that would not be surpassed until Kobe Bryant scored 81 points against the Toronto Raptors in January 2006. The 61 points he scored in Game 5 of the NBA Finals in 1962 is still an NBA Finals record. Over his career, he averaged 27.4 points and 4.3 assists per game. An underrated rebounder, Baylor averaged 13.5 rebounds per game during his career, including a remarkable 19.8 rebounds per game during the 1960-61 season-a season average exceeded by only five other players in NBA history, all of whom were 6 in or taller.

8.2. Major awards and honors

A 10-time All-NBA First Team selection and 11-time NBA All-Star, Baylor was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1977. He was named to the NBA 35th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1980, the NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1996, and the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021. In 2009, SLAM Magazine ranked him number 11 among its Top 50 NBA players of all time. In 2022, to commemorate the NBA's 75th Anniversary, The Athletic ranked Baylor as the 23rd greatest player in NBA history.

Baylor is often listed as the greatest NBA player never to win a championship. However, the Lakers did give Baylor a championship ring for his contributions at the start of the 1971-72 season, which the team went on to win after his retirement.

Fifty-one years after Baylor left Seattle University, the school named its basketball court in his honor on November 19, 2009, now known as the Elgin Baylor Court in Seattle's KeyArena. The Seattle Redhawks also host the annual Elgin Baylor Classic. In June 2017, The College of Idaho had Baylor as one of the inaugural inductees into the school's Hall of Fame. The first biography of Baylor was written by Slam Online contributor Bijan C. Bayne in 2015. On April 6, 2018, a statue of Baylor, designed by Gary Tillery and Omri Amrany, was unveiled at the Staples Center (now Crypto.com Arena) prior to a Lakers game against the Minnesota Timberwolves.

8.3. Criticisms and controversies

Baylor's career was not without its controversies, particularly during his time as an executive. In 2009, he filed an employment discrimination lawsuit against the Los Angeles Clippers, team owner Donald Sterling, team president Andy Roeser, and the NBA. He alleged that he was underpaid and subsequently fired because of his age and race. Although Baylor later dropped the racial discrimination claims, a jury in 2011 sided with the Clippers, finding that his termination was based on the team's poor performance. However, Baylor stated he felt vindicated when Sterling was banned for life from the NBA in 2014 after recordings of him making racist comments were publicized by the press, highlighting the systemic issues Baylor had challenged.

Additionally, a "Curse of Elgin Baylor" has been suggested by some, given his nine appearances in championship finals (NCAA and NBA) without winning a title as a player, and the Los Angeles Clippers' consistent struggles during his long tenure as general manager.

9. Career statistics

Elgin Baylor's career statistics showcase his prolific scoring, rebounding, and all-around abilities throughout his time in the NBA.

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958-59 | Minneapolis | 70 | 40.8 | .408 | .777 | 15.0 | 4.1 | 24.9 |

| 1959-60 | Minneapolis | 70 | 41.0 | .424 | .732 | 16.4 | 3.5 | 29.6 |

| 1960-61 | L.A. Lakers | 73 | 42.9 | .430 | .783 | 19.8 | 5.1 | 34.8 |

| 1961-62 | L.A. Lakers | 48 | 44.4 | .428 | .754 | 18.6 | 4.6 | 38.3 |

| 1962-63 | L.A. Lakers | 80 | 42.1 | .453 | .837 | 14.3 | 4.8 | 34.0 |

| 1963-64 | L.A. Lakers | 78 | 40.6 | .425 | .804 | 12.0 | 4.4 | 25.4 |

| 1964-65 | L.A. Lakers | 74 | 41.3 | .401 | .792 | 12.8 | 3.8 | 27.1 |

| 1965-66 | L.A. Lakers | 65 | 30.4 | .401 | .739 | 9.6 | 3.4 | 16.6 |

| 1966-67 | L.A. Lakers | 70 | 38.7 | .429 | .813 | 12.8 | 3.1 | 26.6 |

| 1967-68 | L.A. Lakers | 77 | 39.3 | .443 | .786 | 12.2 | 4.6 | 26.0 |

| 1968-69 | L.A. Lakers | 76 | 40.3 | .447 | .743 | 10.6 | 5.4 | 24.8 |

| 1969-70 | L.A. Lakers | 54 | 41.0 | .486 | .773 | 10.4 | 5.4 | 24.0 |

| 1970-71 | L.A. Lakers | 2 | 28.5 | .421 | .667 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| 1971-72 | L.A. Lakers | 9 | 26.6 | .433 | .815 | 6.3 | 2.0 | 11.8 |

| Career | 846 | 40.0 | .431 | .780 | 13.5 | 4.3 | 27.4 | |

| All-Star | 11 | 29.2 | .427 | .796 | 9.0 | 3.5 | 19.8 | |

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Minneapolis | 13 | 42.8 | .403 | .770 | 12.0 | 3.3 | 25.5 |

| 1960 | Minneapolis | 9 | 45.3 | .474 | .840 | 14.1 | 3.4 | 33.4 |

| 1961 | L.A. Lakers | 12 | 45.0 | .470 | .824 | 15.3 | 4.6 | 38.1 |

| 1962 | L.A. Lakers | 13 | 43.9 | .438 | .774 | 17.7 | 3.6 | 38.6 |

| 1963 | L.A. Lakers | 13 | 43.2 | .442 | .825 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 32.6 |

| 1964 | L.A. Lakers | 5 | 44.2 | .378 | .775 | 11.6 | 5.6 | 24.2 |

| 1965 | L.A. Lakers | 1 | 5.0 | .000 | ||||

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| 1966 | L.A. Lakers | 14 | 41.9 | .442 | .810 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 26.8 |

| 1967 | L.A. Lakers | 3 | 40.3 | .368 | .750 | 13.0 | 3.0 | 23.7 |

| 1968 | L.A. Lakers | 15 | 42.2 | .468 | .679 | 14.5 | 4.0 | 28.5 |

| 1969 | L.A. Lakers | 18 | 35.6 | .385 | .630 | 9.2 | 4.1 | 15.4 |

| 1970 | L.A. Lakers | 18 | 37.1 | .466 | .741 | 9.6 | 4.6 | 18.7 |

| Career | 134 | 41.1 | .439 | .769 | 12.9 | 4.0 | 27.0 | |