1. Overview

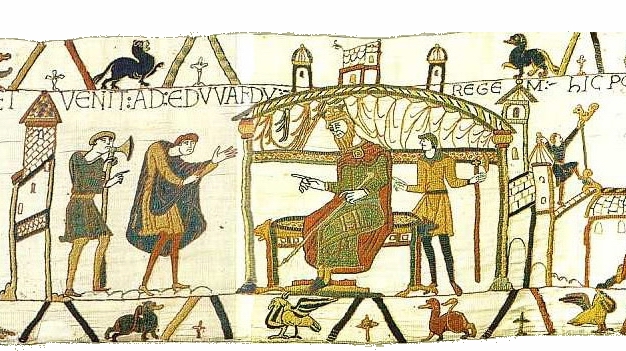

Edward the Confessor, born around 1003 to 1005 and dying on January 5, 1066, was an Anglo-Saxon King of England, traditionally regarded as the last monarch of the House of Wessex. His reign spanned from 1042 until his death, restoring the Wessex line after a period of Danish rule following Cnut the Great's conquest of England in 1016. Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, succeeding his half-brother Harthacnut. His death in 1066, without a clear heir, directly precipitated the Norman Conquest of England later that year, when his wife's brother Harold Godwinson, who succeeded him as king, was defeated and killed by the Normans under William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. Edward's young great-nephew, Edgar Ætheling, was briefly proclaimed king after Hastings but never crowned.

Historians hold differing views on Edward's lengthy 24-year reign. His traditional epithet, "the Confessor," reflects his popular image as an unworldly and pious figure, distinguishing him as a saint who maintained faith without suffering martyrdom, unlike his uncle, Edward the Martyr. Some scholars, such as Richard Mortimer, argue that his reign saw a significant disintegration of royal power in England, largely due to the rising influence of the powerful House of Godwin and the subsequent infighting over succession. In contrast, biographers like Frank Barlow and Peter Rex portray Edward as an effective and capable ruler-energetic, resourceful, and at times ruthless-suggesting that the swift Norman Conquest after his death unfairly tarnished his historical image. The Thai source further notes that his reign was a period where royal authority diminished while the power of the nobility increased, contributing to the circumstances that led to the Norman invasion.

Edward was canonized as a saint by Pope Alexander III in 1161, about a century after his death. He was recognized as one of England's national saints until approximately 1350, when King Edward III designated Saint George as the national patron. Saint Edward's feast day is observed on October 13 by both the Church of England and the Catholic Church, and he is recognized as a patron saint for kings, difficult marriages, separated couples, and vagrants.

2. Early Life and Exile

Edward was born between 1003 and 1005 in Islip, Oxfordshire, the seventh son of Æthelred the Unready and the first by his second wife, Emma of Normandy. He is first mentioned as a witness to two charters in 1005. He had a full brother, Alfred, and a sister, Godgifu. In royal charters, he was consistently listed after his older half-brothers, indicating his lower rank within the royal family.

His childhood was marked by intense Viking raids and invasions led by Sweyn Forkbeard and his son Cnut. In 1013, following Sweyn's seizure of the English throne, Edward's mother, Emma, fled to Normandy, taking Edward and Alfred with her; Æthelred soon followed. After Sweyn's death in February 1014, leading English figures invited Æthelred to return, provided he promised to rule more justly. Æthelred agreed and sent Edward back with his ambassadors. Edward's father died in April 1016, and his older half-brother, Edmund Ironside, continued the fight against Cnut. Scandinavian tradition suggests Edward fought alongside Edmund, though this is disputed given Edward was only around thirteen at the time. Edmund died in November 1016, making Cnut the undisputed king of England. Edward, Alfred, and Godgifu again went into exile. In 1017, Emma married Cnut, and in the same year, Cnut had Edward's last surviving elder half-brother, Eadwig Ætheling, executed.

Edward spent approximately twenty-five years in exile, primarily in Normandy, though his exact location is undocumented until the early 1030s. He likely received financial support from his sister Godgifu, who married Drogo of Mantes, Count of Vexin, around 1024. In the early 1030s, Edward witnessed four charters in Normandy, signing two as "king of England," indicating his continued claim to the throne. The Norman chronicler William of Jumièges recounted that Robert I, Duke of Normandy, Edward's cousin, attempted an invasion of England around 1034 to place Edward on the throne, but the expedition was blown off course to Jersey. Edward also garnered support for his claim from various continental abbots, notably Robert, abbot of the Norman Jumièges Abbey, who would later become Edward's Archbishop of Canterbury. During this period, Edward is said to have developed a deep personal piety, although some modern historians view this as a later construct of the campaign for his canonization, with Frank Barlow describing his lifestyle as that of a "typical member of the rustic nobility." Despite his royal lineage, Edward's prospects of ascending the English throne during his exile appeared slim, as his ambitious mother, Emma, was more focused on supporting Harthacnut, her son by Cnut.

3. Return to England and Accession

In 1035, Cnut died, and his son Harthacnut succeeded him as King of Denmark. His intention regarding England was unclear, and his preoccupation with defending his position in Denmark prevented him from coming to England to assert his claim. Consequently, his elder half-brother Harold Harefoot was appointed regent, while Emma administered Wessex on Harthacnut's behalf.

In 1036, Edward and his brother Alfred independently returned to England. Emma later alleged that they came in response to a forged letter from Harold inviting them to visit her, but historians believe Emma likely invited them herself to counter Harold's growing popularity. Alfred was captured by Godwin, Earl of Wessex, who then handed him over to Harold Harefoot. Harold had Alfred blinded by forcing red-hot pokers into his eyes, a brutal act intended to render him unsuitable for kingship. Alfred died shortly after from his wounds. This murder is widely considered the root of Edward's deep animosity towards Godwin and a primary reason for Godwin's subsequent banishment in 1051. Edward reportedly engaged in a successful skirmish near Southampton before retreating back to Normandy, demonstrating his prudence and contributing to his reputation as a soldier in Normandy and Scandinavia.

In 1037, Harold was recognized as king of England, and the following year, he expelled Emma, who then sought refuge in Bruges. Emma appealed to Edward for aid on behalf of Harthacnut, but Edward, lacking the resources for an invasion, refused and disclaimed any personal interest in the throne. With his position in Denmark now secure, Harthacnut planned an invasion of England, but Harold died in 1040, allowing Harthacnut to cross unopposed with his mother and claim the English throne.

In 1041, Harthacnut invited Edward back to England, likely recognizing him as his heir due to his own declining health. The 12th-century text Quadripartitus states that Edward's return was facilitated by the intervention of Bishop Ælfwine of Winchester and Earl Godwin. Edward met "the thegns of all England" at Hursteshever, possibly near modern-day Hurst Spit opposite the Isle of Wight, where he was formally accepted as king in exchange for an oath to uphold Cnut's laws. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that Edward was sworn in as king alongside Harthacnut. After Harthacnut's death on June 8, 1042, Edward, supported by Godwin, the most powerful English earl, succeeded to the throne. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle highlights his immediate popularity: "before he [Harthacnut] was buried, all the people chose Edward as king in London." Edward was crowned at Winchester Cathedral, the traditional royal seat of the West Saxons, on Easter Sunday, April 3, 1043.

4. Reign

Edward's 24-year reign saw significant political, social, and administrative developments, including the re-establishment of the House of Wessex's authority and shifts in the power dynamics within the English aristocracy.

4.1. Early Reign and Consolidation of Power

Upon his accession, Edward's position was initially precarious. He expressed dissatisfaction with his mother, Emma, for providing insufficient support before and after he became king. In November 1043, accompanied by his three leading earls - Leofric of Mercia, Godwin of Wessex, and Siward of Northumbria - Edward rode to Winchester to seize Emma's property, possibly to reclaim royal treasure she was withholding. Her advisor, Stigand, was temporarily stripped of his bishopric of Elmham in East Anglia, though both were soon restored to favor. Emma died in 1052.

Effective rule for Edward required maintaining good relations with these powerful earls. Loyalty to the ancient House of Wessex had diminished during the preceding Danish rule; only Leofric's family had served Æthelred. Siward was likely Danish, and Godwin, though English, was one of Cnut's "new men," married to Cnut's former sister-in-law. Despite these challenges, Edward, in his early years, successfully re-established the traditional strong monarchy. Frank Barlow characterizes him as "a vigorous and ambitious man, a true son of the impetuous Æthelred and the formidable Emma." Edward's royal lands, though wealthy, were fragmented across the southern earldoms, leaving him without a concentrated personal power base, which he seemingly made no effort to build. In 1050-51, he even disbanded his standing navy of fourteen foreign ships and abolished the tax levied to fund it, a move some historians interpret as a sign of financial weakness or a deliberate shift in policy.

4.2. The House of Godwin and Political Crises

Edward's reign was profoundly shaped by his intricate relationship with the powerful House of Godwin. In 1043, Godwin's eldest son, Sweyn Godwinson, was granted an earldom in the southwest midlands. On January 23, 1045, Edward married Godwin's daughter, Edith of Wessex, further cementing the family's influence. Soon after, Edith's brother Harold Godwinson and their Danish cousin Beorn Estrithson also received earldoms in southern England, effectively placing much of Southern England under the subordinate rule of Godwin and his family. However, this alliance was not without conflict. In 1047, Sweyn was banished for abducting the abbess of Leominster. He attempted to regain his earldom in 1049, but Harold and Beorn, who had likely received Sweyn's lands in his absence, reportedly opposed his return. Sweyn then murdered his cousin Beorn and was exiled again. Edward's nephew Ralph the Timid was granted Beorn's earldom, but the following year, Godwin successfully secured Sweyn's reinstatement.

A major political crisis erupted in 1051-52. Edward and his advisors, showing a preference for candidates without strong local ties, rejected a relative of Godwin chosen by the clergy and monks of Canterbury as Archbishop. Instead, Edward appointed Robert of Jumièges, who then accused Godwin of illegally possessing archiepiscopal estates. In September 1051, Edward's brother-in-law, Eustace II of Boulogne, visited and his men caused an affray in Dover. Edward ordered Godwin, as Earl of Kent, to punish the town's burgesses, but Godwin sided with them and refused the royal command. Edward saw this as an opportunity to curb his over-mighty earl. Archbishop Robert further inflamed the situation by accusing Godwin of plotting to murder the king, echoing the murder of Edward's brother Alfred in 1036. Leofric and Siward, supporting the king, raised their vassals, while Sweyn and Harold also mobilized their forces. However, neither side desired open conflict, and Godwin and Sweyn reportedly gave their sons as hostages, sending them to Normandy. The Godwin family's position crumbled as their retainers were unwilling to fight the king. When Stigand, acting as an intermediary, conveyed the king's sarcastic remark that Godwin could have peace if he could restore Alfred and his companions alive, Godwin and his sons fled to Flanders and Ireland. Edward then repudiated Queen Edith, sending her to a nunnery, possibly due to her childlessness, and Archbishop Robert even urged their divorce.

A year later, Godwin and his remaining sons returned with an army, garnering significant support, while Leofric and Siward failed to uphold the king. Both factions feared a civil war that would leave England vulnerable to foreign invasion. Despite his fury, Edward was compelled to concede, restoring Godwin and Harold to their earldoms. In turn, Robert of Jumièges and other French advisors fled, fearing Godwin's retribution. Edith was reinstated as queen, and Stigand, who had again mediated the crisis, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in Robert's place. Stigand controversially retained his existing bishopric of Winchester, and this pluralism became a persistent source of conflict with the Pope.

4.3. Foreign Policy and Defence

Throughout the 1050s, Edward pursued an assertive and generally successful foreign policy towards England's northern and western neighbors.

In his relations with Scotland, Edward leveraged internal conflicts to his advantage. Malcolm Canmore, whose father, Duncan I of Scotland, was killed in battle in 1040 by forces led by Macbeth, sought refuge at Edward's court. In 1054, Edward dispatched Siward to invade Scotland. Siward defeated Macbeth, and Malcolm, who accompanied the expedition, secured control over southern Scotland. By 1058, Malcolm had personally killed Macbeth in battle and ascended the Scottish throne. He visited Edward in 1059, but in 1061, he began raiding Northumbria, aiming to incorporate it into his domain.

Edward also demonstrated resolve in dealing with Wales. In 1053, he ordered the assassination of the South Welsh prince Rhys ap Rhydderch as retaliation for a raid on England; Rhys's head was delivered to the king. In 1055, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn consolidated his rule over Wales and formed an alliance with Ælfgar of Mercia, who had been outlawed for treason. Together, they defeated Earl Ralph at Hereford, forcing Harold Godwinson to assemble forces from nearly all of England to repel the invaders back into Wales. Peace was eventually concluded with the reinstatement of Ælfgar, who succeeded as Earl of Mercia upon his father's death in 1057. Gruffydd swore an oath acknowledging Edward as his faithful overlord. Ælfgar likely died in 1062, and his young son Edwin was permitted to succeed as Earl of Mercia. However, Harold then launched a surprise attack on Gruffydd, who managed to escape. When Harold and his brother Tostig attacked again the following year, Gruffydd retreated and was ultimately killed by Welsh adversaries. Edward and Harold were subsequently able to impose vassalage on several Welsh princes.

4.4. Later Reign and Withdrawal from Politics

Until the mid-1050s, Edward managed to strategically structure his earldoms to prevent the complete dominance of the Godwin family. Godwin died in 1053, and although Harold succeeded him as Earl of Wessex, none of his other brothers held earldoms at that time, making the Godwin house less powerful than it had been since Edward's accession. However, a series of deaths between 1055 and 1057 drastically altered the control of earldoms. In 1055, Siward died; his son was deemed too young to govern Northumbria, leading to the appointment of Harold's brother, Tostig Godwinson. In 1057, Leofric and Ralph the Timid died; Leofric's son Ælfgar succeeded as Earl of Mercia, and Harold's brother Gyrth Godwinson replaced Ælfgar as Earl of East Anglia. The fourth surviving Godwin brother, Leofwine Godwinson, was granted an earldom in the southeast, carved from Harold's own territory, with Harold receiving Ralph's former lands in compensation. By 1057, the Godwin brothers effectively controlled all of England, with the exception of Mercia. It is unclear whether Edward approved of this consolidation of power or was forced to accept it, but from this point, he appears to have increasingly withdrawn from active politics, dedicating himself to hunting, a pursuit he engaged in daily after attending church.

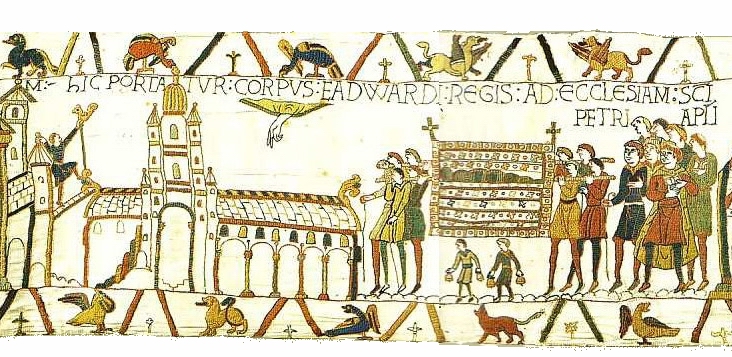

In October 1065, while Edward was hunting with Harold's brother, Tostig, then Earl of Northumbria, Tostig's thegns in Northumbria rebelled against his perceived oppressive rule, killing approximately 200 of his followers. They nominated Morcar, the brother of Edwin of Mercia, as earl and invited Morcar and Edwin to march south and join them. They met Harold at Northampton, where Tostig accused Harold before the king of conspiring with the rebels. Tostig, favored by both the king and queen, demanded that the revolt be suppressed. However, neither Harold nor any other magnate would commit to fighting in support of Tostig. Edward was compelled to accept Tostig's banishment, a humiliation that may have precipitated a series of strokes leading to his death. He was too frail to attend the consecration of his new church at Westminster Abbey, which had been largely completed in 1065, on December 28.

5. Westminster Abbey

Edward's Norman leanings are most evident in the significant architectural project of his reign: Westminster Abbey. This was the first Romanesque church constructed in England in the Norman style. Commissioned between 1042 and 1052, it was intended as a royal burial church. Its consecration took place on December 28, 1065, shortly before Edward's death, though it was only fully completed around 1090. The original abbey was later demolished in 1245 to make way for Henry III's new edifice, which stands today. Edward's Abbey bore a striking resemblance to Jumièges Abbey in Normandy, which was being built concurrently. Robert, Edward's Archbishop of Canterbury, must have been intimately involved in the design and construction of both, although it remains unclear which served as the architectural inspiration for the other.

Although Edward does not appear to have been particularly interested in books or associated arts, his patronage of Westminster Abbey was pivotal in the development of English Romanesque architecture, showcasing him as an innovative and generous patron of the Church. According to the Korean source, Edward vowed during his Norman exile that if he regained his throne, he would undertake a pilgrimage to Rome. After his accession, when political instability prevented him from fulfilling this vow, Pope Leo IX advised him instead to build a monastery and assist the poor with the pilgrimage funds. Edward followed this counsel, ordering the expansion of the existing monastery, which became the foundation of Westminster Abbey. After the reign of Henry III, successive English monarchs were crowned in the Abbey built by Edward, where they pledged to uphold "Edward's Law." Although such a unified body of law attributable solely to Edward likely did not exist, the Abbey became a symbol of his idealized legacy and contributed to his later canonization.

6. Succession Crisis and the Norman Conquest

Historians have long debated Edward's intentions regarding his succession, with the discussion beginning as early as the 12th century with William of Malmesbury. One school of thought, largely based on Norman claims, asserts that Edward consistently intended for William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, to be his heir. This view often accepts the medieval assertion that Edward had already resolved to remain celibate before his marriage to Edith, thus precluding the possibility of a direct heir. However, most modern historians believe that Edward genuinely hoped to have a child with Edith, at least until their significant quarrel in 1051. William the Conqueror shared a familial tie with Edward, as William's grandfather, Richard II, Duke of Normandy, was the brother of Edward's mother, Emma of Normandy, making them first cousins once removed. William may have visited Edward during Godwin's exile, and it is believed that Edward promised William the succession at that time, though historians disagree on the seriousness of this promise and whether Edward later changed his mind.

The strongest legitimate claim to be Edward's heir belonged to Edward the Exile, the son of Edward's elder half-brother, Edmund Ironside. Edward the Exile had been taken to Hungary as a young child. In 1054, Bishop Ealdred of Worcester traveled to the Holy Roman Empire to secure his return, likely with the intent of positioning him as Edward's successor. The Exile returned to England in 1057 with his family but died almost immediately. His son, Edgar Ætheling, who was then around six years old, was subsequently raised at the English court. He was given the designation Ætheling, meaning "throne-worthy," which suggests that Edward might have considered him as an heir. Indeed, Edgar was briefly proclaimed king after Harold's death in 1066. However, Edgar's absence from the witness lists of Edward's diplomas and the lack of evidence in the Domesday Book that he held substantial land indicate that he was marginalized towards the end of Edward's reign.

After the mid-1050s, Edward increasingly withdrew from active governance, becoming more dependent on the Godwin family. It is possible he became resigned to the idea that one of them would eventually succeed him. Norman accounts claim that Edward dispatched Harold to Normandy around 1064 to confirm the promise of succession to William. The most compelling evidence for this comes from the Norman apologist William of Poitiers. According to his narrative, shortly before the Battle of Hastings, Harold sent an envoy to William who admitted that Edward had promised the throne to William, but argued that this promise was superseded by Edward's deathbed pledge to Harold. In his reply, William did not dispute the deathbed promise but maintained that Edward's earlier promise to him took precedence. In the view of historian Stephen Baxter, Edward's handling of the succession issue was "dangerously indecisive," a factor that significantly "contributed to one of the greatest catastrophes to which the English have ever succumbed"-the Norman Conquest.

7. Death and Burial

Edward the Confessor likely entrusted the kingdom to Harold Godwinson and Queen Edith shortly before his death. He died at Westminster on January 5, 1066. On January 6, he was buried in his newly constructed Westminster Abbey. In a testament to the immediate and pressing succession crisis, Harold Godwinson was crowned King of England on the very same day as Edward's burial.

8. Veneration and Sainthood

Edward the Confessor holds a unique place as the only King of England to be canonized by the Pope, yet he was part of a broader tradition of (uncanonized) Anglo-Saxon royal saints, such as Eadburh of Winchester and Edith of Wilton. Modern historians often view Edward as an unlikely candidate for sainthood, citing his documented proneness to fits of rage and his fondness for hunting, suggesting his canonization was primarily a political act. However, some argue that the early emergence of his cult indicates a credible foundation for his sanctity.

Edward's approach to church appointments often reflected a more worldly perspective. In 1051, when he appointed Robert of Jumièges as Archbishop of Canterbury, he selected the prominent craftsman Spearhafoc to succeed Robert as Bishop of London. Robert, however, refused to consecrate Spearhafoc, claiming papal prohibition. Despite this, Spearhafoc occupied the bishopric for several months with Edward's backing. After the Godwin family fled the country during the 1051-52 crisis, Edward expelled Spearhafoc, who reportedly fled with a substantial amount of gold and gems that had been entrusted to him for the making of a crown for Edward. Stigand, who replaced Robert of Jumièges as Archbishop of Canterbury, was notable as the first non-monastic archbishop in nearly a century. He faced excommunication from several popes due to his controversial practice of holding both the sees of Canterbury and Winchester simultaneously. This irregularity led several bishops to seek consecration abroad. Edward generally favored clerks over monks for the most important and wealthiest bishoprics and likely accepted gifts from candidates seeking bishoprics and abbacies, though his appointments were broadly considered respectable. When Odda of Deerhurst died without heirs in 1056, Edward seized lands Odda had granted to Pershore Abbey and instead bestowed them upon his Westminster foundation. Historian Ann Williams notes that in the 11th century, "the Confessor did not... have the saintly reputation which he later enjoyed, largely through the efforts of the Westminster monks themselves."

Following 1066, a subdued cult of Edward as a saint gradually developed, possibly initially discouraged by the early Norman abbots of Westminster, but gaining momentum in the early 12th century. Osbert of Clare, the prior of Westminster Abbey, spearheaded a campaign for Edward's canonization, seeking to augment the Abbey's wealth and influence. By 1138, Osbert had transformed the Vita Ædwardi Regis, a life of Edward commissioned by his widow, into a conventional saint's life. He interpreted an ambiguous passage in the Vita regarding Edward's marriage to Edith-which might have implied a chaste union-to claim that Edward had been celibate, perhaps to absolve Edith of blame for her childlessness. In 1139, Osbert traveled to Rome to petition for Edward's canonization with the support of King Stephen, but he lacked the full endorsement of the English ecclesiastical hierarchy, and Stephen was embroiled in a dispute with the Church. Consequently, Pope Innocent II postponed a decision, stating that Osbert's testimonials of Edward's holiness were insufficient.

The opportunity for canonization arose in 1159 amidst a disputed papal election. Henry II's crucial support helped secure the recognition of Pope Alexander III. In 1160, Laurence, the new abbot of Westminster, capitalized on this, renewing Edward's claim. This time, the petition received the full backing of both the king and the English hierarchy. A grateful Pope Alexander III issued the bull of canonization on February 7, 1161, a convergence of interests between Westminster Abbey, King Henry II, and Pope Alexander III. Edward was granted the title "Confessor," a designation for a person believed to have led a saintly life but who did not suffer martyrdom. In the 1230s, King Henry III developed a strong devotion to the cult of Saint Edward. He commissioned a new biography of Edward by Matthew Paris and, in 1269, constructed a magnificent new tomb for the saint within a rebuilt Westminster Abbey. Henry III further honored Edward by naming his eldest son, the future Edward I, after him.

Until approximately 1350, Edmund the Martyr, Gregory the Great, and Edward the Confessor were revered as England's national saints. However, Edward III, preferring the more war-like figure of Saint George, established the Order of the Garter in 1348 with Saint George as its patron. The chapel of Saint Edward the Confessor at Windsor Castle was subsequently re-dedicated to Saint George, who was formally acclaimed as patron of the English race in 1351. While Edward became a less popular saint for many, but he remained particularly significant to the Norman dynasty, which asserted its legitimacy by claiming to be the successor to Edward, the last legitimate Anglo-Saxon king.

The shrine of Saint Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey remains at its location following the final translation of his body to a chapel east of the sanctuary by Henry III on October 13, 1269. His translation day, October 13 (which also marked his first translation in 1163), is observed as an optional memorial in the Catholic dioceses of England. Saint Edward may also be commemorated on the anniversary of his death, January 5, the date he is listed in the Martyrologium Romanum. The Church of England's calendar of saints designates October 13 as a Lesser Festival. Each October, Westminster Abbey hosts a week of festivities and prayers in his honor. Edward is also revered as a patron saint for difficult marriages.

9. Historical Assessment and Legacy

Edward the Confessor's reign and impact are subject to varied historical interpretations, shaping his lasting legacy on English monarchy, society, and culture.

9.1. Positive Assessment

Edward is often positively assessed for his deep personal piety and profound patronage of the Church, most notably exemplified by his commission and construction of Westminster Abbey. This significant architectural undertaking not only served as a royal burial site but also established a prominent center of religious devotion. His devoutness contributed to an idealized image as a just and saintly ruler in the centuries following his death, an image actively promoted by the monks of Westminster Abbey and later kings who sought to legitimize their own rule through association with his sanctity. Despite historical debates about his political effectiveness, his personal faith and commitment to religious foundations are consistently highlighted as positive aspects of his character and reign.

9.2. Criticism and Controversy

Despite his saintly image, Edward's reign has faced considerable criticism. Historians often point to a perceived political weakness, characterized by his increasing withdrawal from active governance, particularly in his later years. This disengagement led to the dominance of powerful noble families, most notably the House of Godwin, which consolidated immense power throughout England. Critics also highlight his reliance on foreign advisors, particularly Normans, which generated resentment among the Anglo-Saxon nobility and populace, contributing to internal political tensions.

The unresolved succession issue is perhaps the most significant point of controversy. Edward's failure to secure a clear and universally accepted heir directly contributed to the instability that culminated in the Norman Conquest. His fluctuating intentions regarding succession, alternating between potential Norman claimants and Anglo-Saxon relatives, and the alleged deathbed promise to Harold Godwinson, created a dangerous power vacuum. This indecisiveness is seen as having a profound negative impact on royal power and overall social stability, setting the stage for one of England's most transformative and violent periods. Furthermore, historical accounts suggest Edward was not above accepting bribes; the Ramsey Liber Benefactorum records an instance where he allegedly accepted 20 marks in gold and his wife 5 marks for a favorable judgment, indicating a more worldly approach than his saintly image often portrays. His rule has been described as that of a "monk more than a king," characterized by a "soft and inactive" approach that missed opportunities to stabilize the Anglo-Saxon state, ultimately laying the groundwork for the Norman Conquest through his trust in Normans.

9.3. Impact on England

Edward the Confessor's reign left a multifaceted legacy on England. Architecturally, his most enduring contribution is the original Westminster Abbey, which, as England's first Norman Romanesque church, significantly influenced subsequent English architecture. This project not only demonstrated his innovative patronage of the Church but also established a new precedent for royal burial and coronation sites.

Symbolically, Edward's role in shaping royal legitimacy became profound. The Norman dynasty, eager to present themselves as rightful successors rather than mere conquerors, actively cultivated the idea that William the Conqueror was Edward's designated heir. This narrative solidified Edward's image as the last legitimate Anglo-Saxon king, whose succession was supposedly violated, thereby justifying the Norman invasion as a restoration of order rather than an usurpation. After his canonization, Edward became a potent symbol of "free England" preceding the Conquest, embodying a idealized past where "Edward's Law" (though no such codified laws existed from his reign) represented a period of peace and justice. This symbolic role continued to resonate through subsequent centuries, influencing the identity of the English monarchy and providing a narrative of continuity even after such a dramatic dynastic shift. His actions, or inactions, regarding the succession undeniably had a lasting impact, leading directly to the pivotal events of 1066 and fundamentally altering the course of English history, society, and culture.

10. Personal Life and Character

Edward the Confessor's personal attributes and character are portrayed with a mix of idealized and more realistic descriptions. The Vita Ædwardi Regis, a contemporary biography, describes him as "a very proper figure of a man - of outstanding height, and distinguished by his milky white hair and beard, full face and rosy cheeks, thin white hands, and long translucent fingers; in all the rest of his body he was an unblemished royal person." This account further paints him as "pleasant, but always dignified, he walked with eyes downcast, most graciously affable to one and all. If some cause aroused his temper, he seemed as terrible as a lion, but he never revealed his anger by railing." As historian Richard Mortimer notes, this portrayal contains clear elements of an idealized king, presented in flattering terms.

Other sources provide additional details and a more balanced view. The Korean source mentions he had a tall stature, pale white skin, and silver-blonde hair. While his saintly image emphasizes his piety and monastic inclinations, some accounts suggest a contrasting temperament, including a tendency for fits of rage, as noted by historians discussing his suitability for sainthood.

His relationship with his wife, Edith of Wessex, Godwin's daughter, was also a subject of historical interest. While they were married in 1045, some historical interpretations, particularly those promoting his celibacy for canonization purposes, suggest that their marriage was chaste and that Edward deliberately chose not to have an heir, prioritizing his personal vow of purity over dynastic concerns. This interpretation, however, is debated by modern historians, many of whom believe he likely desired an heir, at least until the political crisis of 1051.