1. Life and Career

Theodor Seuss Geisel's life and career spanned nearly a century, marked by significant creative output and shifts in focus from early illustration and wartime propaganda to his enduring legacy in children's literature.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Theodor Seuss Geisel was born and raised in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, Theodor Robert Geisel, initially managed the family brewery. However, due to Prohibition, the brewery was forced to close, and his father was later appointed to supervise Springfield's public park system by Mayor John A. Denison. His mother was Henrietta Geisel (née Seuss), whose maiden name became his famous pen name. The family was of German descent, and Geisel was raised as a Missouri Synod Lutheran, a denomination he maintained throughout his life. His boyhood home on Fairfield Street in Springfield was near Mulberry Street, which he later immortalized in his first children's book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

Geisel attended Dartmouth College, graduating in 1925. During his time there, he joined the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity and contributed to the humor magazine Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, eventually becoming its editor-in-chief. A notable incident occurred when he was caught drinking gin with friends in his room, an illegal act under Prohibition laws. As a consequence, Dean Craven Laycock insisted Geisel resign from all extracurricular activities, including the Jack-O-Lantern. To circumvent this, Geisel began signing his work with the pen name "Seuss." He was greatly influenced in his writing by W. Benfield Pressey, a professor of rhetoric at Dartmouth, whom he called his "big inspiration for writing."

Upon graduating from Dartmouth, Geisel pursued further studies at Lincoln College, Oxford, with the intention of earning a Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) in English literature. It was at Oxford that he met his future wife, Helen Palmer. Palmer recognized his talent for drawing animals, recalling that his notebooks were "always filled with these fabulous animals," and encouraged him to pursue drawing professionally instead of becoming an English teacher.

1.2. Early Career

Geisel left Oxford in February 1927 without completing his degree and returned to the United States. He immediately began submitting his writings and drawings to various magazines, book publishers, and advertising agencies. His first nationally published cartoon appeared in The Saturday Evening Post on July 16, 1927, earning him $25 and motivating him to move from Springfield to New York City. Later that year, he accepted a position as a writer and illustrator at the humor magazine Judge. Feeling financially stable, he married Helen Palmer on November 29, 1927. His first work signed "Dr. Seuss" was published in Judge about six months after he joined the magazine.

In early 1928, one of Geisel's cartoons for Judge featured Flit, a popular bug spray produced by Standard Oil of New Jersey. This cartoon caught the attention of an advertising executive's wife, leading to Geisel's first Flit advertisement appearing on May 31, 1928. The campaign, which continued until 1941, featured the memorable catchphrase "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" which became a part of popular culture and was even used by comedians like Fred Allen and Jack Benny. As his reputation grew through the Flit campaign, Geisel's work became highly sought after, appearing regularly in prominent magazines such as Life, Liberty, and Vanity Fair.

The income from his advertising work and magazine submissions made Geisel quite prosperous. This financial stability allowed him and Helen to move into better living quarters and engage with higher social circles, including befriending the wealthy family of banker Frank A. Vanderlip. They also traveled extensively, visiting 30 countries by 1936. Despite his focus on children's books later in life, Geisel and Helen did not have children of their own. Geisel felt that travel fueled his creativity. His advertising success led to further contracts with companies like Ford Motor Company, NBC Radio Network, and Holly Sugar. In 1931, Viking Press published his first foray into books, Boners, a collection of illustrated children's sayings that became a The New York Times non-fiction bestseller and led to a sequel. Despite this early success, an ABC book featuring "very strange animals" that he wrote and illustrated failed to secure a publisher.

In 1936, while returning from a European ocean voyage, the rhythmic hum of the ship's engines inspired the poem that would become his first children's book: And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. This book faced numerous rejections, reportedly between 20 and 43 publishers. According to Geisel, he was on his way to burn the manuscript when a chance encounter with an old Dartmouth classmate led to its publication by Vanguard Press. Before the United States entered World War II, Geisel published four more books: The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1938), The King's Stilts (1939), and The Seven Lady Godivas (1939), all written in prose, which was atypical for him. This was followed by Horton Hatches the Egg in 1940, marking his return to verse.

1.3. World War II-Era Work

As World War II intensified, Geisel shifted his focus to political cartoons, producing over 400 in two years as an editorial cartoonist for the left-leaning New York City daily newspaper, PM.

1.3.1. Political Cartoons

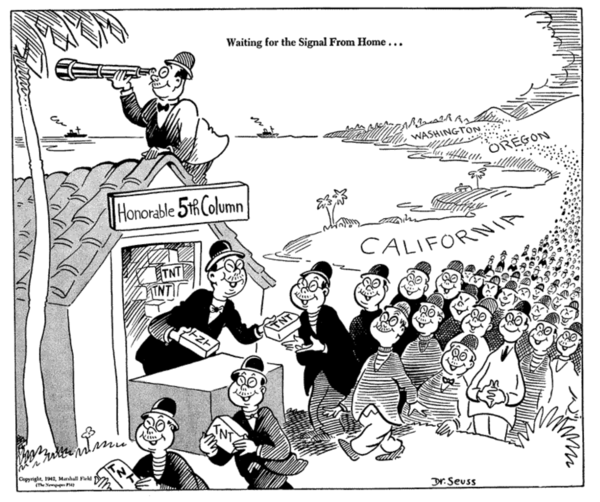

Geisel's political cartoons, later collected in Dr. Seuss Goes to War, strongly condemned Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and were highly critical of non-interventionists, or "isolationists," such as Charles Lindbergh, who opposed US entry into the war. He depicted the fear of communism as exaggerated, identifying greater threats from groups like the House Committee on Unamerican Activities and those who advocated cutting the U.S.'s "life line" to the USSR and Joseph Stalin, whom he once controversially portrayed as a porter carrying "our war load."

However, Geisel's wartime cartoons also contained deeply troubling racial caricatures. One cartoon depicted Japanese Americans with exaggerated, stereotypical features-buckteeth, glasses, and slanted eyes-being handed TNT in anticipation of a "signal from home," suggesting they were a fifth column awaiting orders from Japan to commit sabotage on American soil. These depictions contributed to the harmful stereotype and incitement of discrimination against Japanese Americans during a period of widespread internment. Despite this, other cartoons by Geisel from the same period deplored the racism at home against Jews and black individuals, arguing that such prejudice harmed the overall war effort. His cartoons were generally supportive of President Roosevelt's handling of the war, combining exhortations to ration and contribute with frequent attacks on Congress (particularly the Republican Party), parts of the press (including the New York Daily News, Chicago Tribune, and Washington Times-Herald), and other critics whom he believed were intentionally or inadvertently fostering disunity and aiding the Nazis.

1.3.2. War-Related Film Production

In 1942, Geisel dedicated his efforts to directly supporting the U.S. war effort. He initially created posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. In 1943, he joined the Army as a captain and was appointed commander of the Animation Department within the First Motion Picture Unit of the United States Army Air Forces. In this role, he wrote films including Your Job in Germany, a 1945 propaganda film about establishing peace in Europe after World War II, and Our Job in Japan. He also contributed to the Private Snafu series, which consisted of adult army training films. For his service in the Army, Geisel was awarded the Legion of Merit. His work on Our Job in Japan later formed the basis for Design for Death (1947), a commercially released film exploring Japanese culture, which earned an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film. Additionally, Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950), an animated short film based on an original story by Geisel, received the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film.

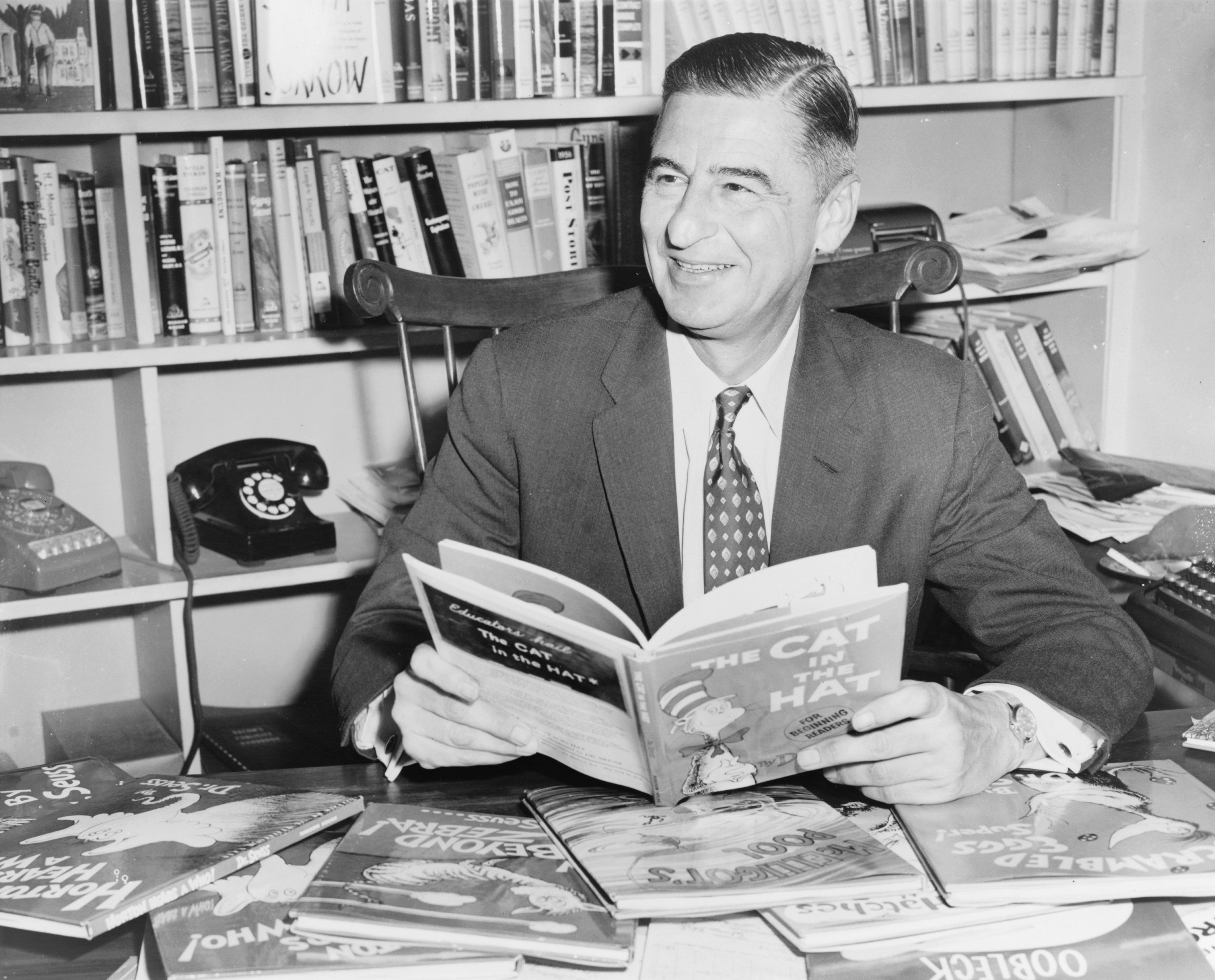

1.4. Later Career and Literary Achievements

After the conclusion of World War II, Geisel and his wife relocated to the La Jolla community of San Diego, California, where he returned to his primary focus of writing children's books. He published most of his works through Random House in North America and William Collins, Sons (later HarperCollins) internationally. During this period, he produced many of his most beloved and enduring books, including If I Ran the Zoo (1950), Horton Hears a Who! (1955), If I Ran the Circus (1956), The Cat in the Hat (1957), How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), and Green Eggs and Ham (1960). While he never won the prestigious Caldecott Medal or the Newbery Medal, three of his titles were recognized as Caldecott Honor books (formerly runners-up): McElligot's Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950). In 1953, Dr. Seuss also wrote the musical film and fantasy film The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.; however, the movie was a critical and financial failure, leading Geisel to never attempt another feature film. Throughout the 1950s, he also published numerous illustrated short stories, primarily in Redbook magazine, some of which were later collected (e.g., in The Sneetches and Other Stories) or expanded into independent books.

A pivotal moment in his career occurred in May 1954 when Life magazine published a report on illiteracy among schoolchildren, concluding that children were disengaged from reading due to boring textbooks. William Ellsworth Spaulding, then director of the education division at Houghton Mifflin, compiled a list of 348 words he deemed essential for first-graders. He challenged Geisel to reduce this list to 250 words and write a book using only those words, urging him to "bring back a book children can't put down." Nine months later, Geisel completed The Cat in the Hat, utilizing 236 of the provided words. This book masterfully combined Geisel's characteristic drawing style, verse rhythms, and imaginative power with a simplified vocabulary, making it accessible to beginning readers. The Cat in the Hat and subsequent books specifically designed for young children achieved immense international success and remain highly popular. For instance, in 2009, Green Eggs and Ham sold 540,000 copies, The Cat in the Hat sold 452,000 copies, and One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish (1960) sold 409,000 copies, outperforming the majority of newly published children's books. Geisel continued to write many more children's books, some maintaining his simplified-vocabulary style (marketed as Beginner Books) and others reverting to his earlier, more elaborate approach.

In 1955, Dartmouth College honored Geisel with an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters. The citation acknowledged his unique ability to captivate children and parents alike with his imaginative creations and recognized the intelligence, kindness, and humanity underlying his humor. Geisel humorously remarked that he would now have to sign his name "Dr. Dr. Seuss." Due to his wife Helen's illness, he delayed accepting the honor until June 1956.

Geisel's wife Helen struggled with prolonged illnesses. Tragically, on October 23, 1967, Helen died by suicide. On August 5, 1968, Geisel married Audrey Dimond, with whom he had reportedly been having an affair. Despite dedicating much of his life to children's literature, Theodor Geisel never had children of his own, famously quipping, "You have 'em; I'll entertain 'em." Audrey confirmed this, stating that Geisel "lived his whole life without children and he was very happy without children." Audrey oversaw Geisel's literary estate until her death on December 19, 2018, at the age of 97.

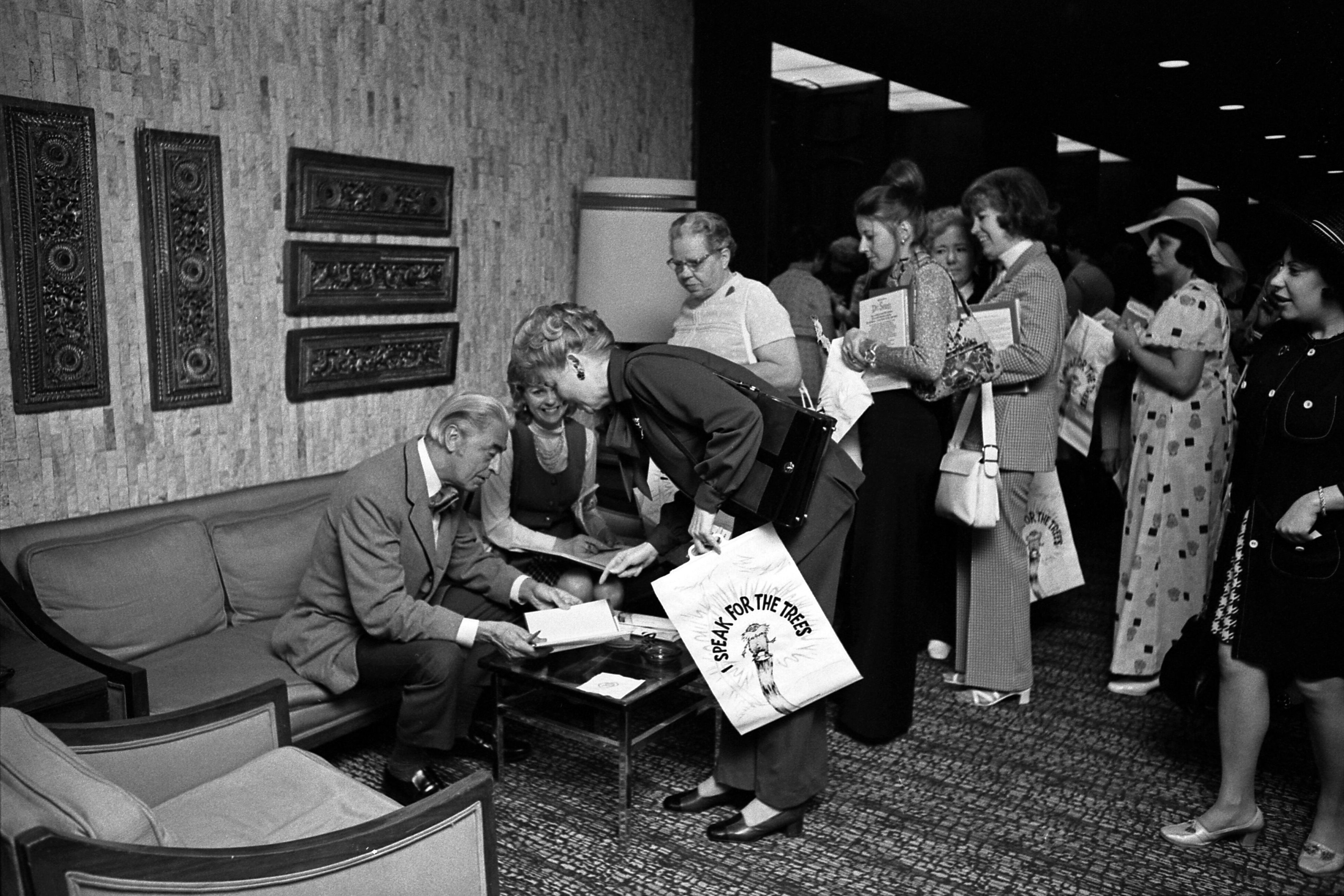

In 1980, Geisel received an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters (L.H.D.) from Whittier College. The same year, he was awarded the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal by professional children's librarians from the Association for Library Service to Children, acknowledging his "substantial and lasting contributions to children's literature." This award was given every five years at the time. In 1984, he received a special Pulitzer Prize for his "contribution over nearly half a century to the education and enjoyment of America's children and their parents."

2. Pen Names

Theodor Seuss Geisel used several pen names throughout his career, each with its own story. His most famous, "Dr. Seuss," is commonly pronounced 'sooss' in an anglicized manner, though his family, and Geisel himself, pronounced "Seuss" as 'zoyss', rhyming with "voice." Alexander Laing, a collaborator on the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, penned a verse to clarify the pronunciation:

You're wrong as the deuce

And you shouldn't rejoice

If you're calling him Seuss.

He pronounces it Soice (or Zoice)

Geisel adopted the anglicized pronunciation because it "evoked a figure advantageous for an author of children's books to be associated with-Mother Goose" and because it was the pronunciation most people naturally used. He added "Doctor" to his pen name as a nod to his father, who had always hoped his son would pursue a career in medicine.

For books that Geisel wrote but others illustrated, he used the pen name "Theo LeSieg." This name is simply "Geisel" spelled backward, and he began using it with the publication of I Wish That I Had Duck Feet in 1965.

Geisel also published one book, Because a Little Bug Went Ka-Choo!! (1975), under the pseudonym "Rosetta Stone." This collaborative work with Michael K. Frith chose the name to honor Geisel's second wife, Audrey, whose maiden name was Stone.

3. Political Views

Theodor Seuss Geisel was a liberal Democrat and a staunch supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal policies. His early political cartoons demonstrated a passionate opposition to fascism, advocating for intervention before and after the U.S. entered World War II. He depicted the widespread fear of communism as exaggerated, identifying greater threats from domestic forces such as the House Committee on Unamerican Activities and those who criticized aid to the Soviet Union or Joseph Stalin.

However, Geisel's wartime political cartoons also contained deeply problematic and prejudiced portrayals. He supported the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, believing it was necessary to prevent potential sabotage. His stance at the time was articulated bluntly: "But right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: 'Brothers!' It is a rather flabby battle cry. If we want to win, we've got to kill Japs, whether it depresses John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left." This statement reflects a regrettable aspect of his views during the war, demonstrating a clear racial animosity. After the war, Geisel re-evaluated his perspective, acknowledging his past animosity. His book Horton Hears a Who! (1954) is often interpreted as an allegory for the American post-war occupation of Japan and was notably dedicated to a Japanese friend, signifying a personal atonement.

Later in his career, Geisel converted a copy of his children's book, Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now!, into a polemic targeting U.S. President Richard Nixon shortly before the end of the Watergate scandal (1972-1974), which saw Nixon's resignation. He replaced the main character's name throughout the book, retitling it "Richard M. Nixon, Will You Please Go Now!" This version was published in major newspapers through the column of his friend Art Buchwald.

The line "a person's a person, no matter how small" from Horton Hears a Who! has been widely adopted as a slogan by the pro-life movement in the United States. Geisel himself and, later, his widow Audrey, objected strongly to this use. According to Audrey Geisel's attorney, "She doesn't like people to hijack Dr. Seuss characters or material to front their own points of view." In the 1980s, Geisel reportedly threatened to sue an anti-abortion group for using this phrase on their stationery, which led to its removal. While his biographer stated that Geisel never publicly expressed an opinion on abortion, Audrey Geisel later provided financial support to Planned Parenthood, indicating her stance on reproductive rights.

3.1. Messages in Children's Books

Despite his political leanings, Geisel made a point of not explicitly starting his stories with a moral in mind, famously stating that "kids can see a moral coming a mile off." However, he acknowledged that "there's an inherent moral in any story" and once remarked that he was "subversive as hell."

Indeed, Geisel's children's books subtly and explicitly convey his views on a wide array of social and political issues. The Lorax (1971) stands as a powerful allegory for environmentalism and anti-consumerism. The Sneetches (1961) addresses themes of racial equality and the absurdity of discrimination based on superficial differences. The Butter Battle Book (1984) serves as a commentary on the arms race and the dangers of escalating conflict. Yertle the Turtle (1958) is a pointed critique of Adolf Hitler and anti-authoritarianism, illustrating the pitfalls of tyranny. How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957) critiques the economic materialism and consumerism often associated with the Christmas season. Finally, Horton Hears a Who! (1954) champions anti-isolationism and internationalism, emphasizing the importance of protecting the vulnerable and advocating for marginalized voices regardless of their size.

3.2. Controversies and Retired Books

Over time, Dr. Seuss's work for children has faced increasing criticism for containing unconscious racist themes and problematic portrayals. A 2019 academic paper published in "Research on Diversity in Youth Literature" examined 50 of Geisel's works and found that 43 out of 45 characters of color exhibited Orientalist characteristics. The paper also highlighted Geisel's earlier anti-Black and anti-Semitic cartoons from the 1920s, in addition to his World War II anti-Japanese propaganda.

In response to these criticisms and in an effort to ensure its catalog represents and supports all communities and families, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the organization managing the rights to his works, announced on March 2, 2021, that it would cease publication and licensing of six specific books. The titles are And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937), If I Ran the Zoo (1950), McElligot's Pool (1947), On Beyond Zebra! (1955), Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953), and The Cat's Quizzer (1976). The organization stated that these books "portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong."

This decision sparked significant public debate. Some conservative commentators and politicians criticized the move as an example of "cancel culture," arguing against what they perceived as an overreach of political correctness. However, this perspective has also been challenged. For instance, in 2024, a Republican-backed law in Tennessee led to the removal of many books from school libraries, including some by Dr. Seuss, ironically by a political faction that had previously decried "cancel culture" affecting his works. This demonstrated that scrutiny over appropriateness in literature is not limited to one political ideology but can manifest in different forms across the political spectrum.

4. Artistic Style

Theodor Seuss Geisel's artistic style is instantly recognizable, characterized by its unique blend of poetic rhythm and distinctive visual elements.

4.1. Poetic Meter and Literary Devices

Geisel primarily wrote most of his books in anapestic tetrameter, a poetic meter that has been used by many poets throughout English literary history. This distinctive rhythmic structure, which features two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable, often repeated four times per line, is widely considered one of the key reasons for the enthusiastic reception of Geisel's writing. His frequent use of alliteration, assonance, and invented words further contributed to the musicality and memorability of his stories, captivating young readers and making his books enjoyable to read aloud.

4.2. Artwork and Visual Characteristics

Geisel's early artwork, particularly his commercial illustrations, often utilized the shaded textures of pencil drawings or watercolors. However, in his children's books published after World War II, he generally transitioned to a starker medium: pen and ink. These illustrations typically used only black, white, and one or two additional colors, creating a bold and simplified visual style. Later books, such as The Lorax, incorporated a wider range of colors.

Geisel's visual style was unique and immediately identifiable. His figures are frequently depicted as "rounded" and somewhat droopy, a characteristic seen in the faces of both the Grinch and the Cat in the Hat. A striking feature of his illustrations is the deliberate avoidance of straight lines for buildings and machinery, even when representing real-world objects. For example, If I Ran the Circus features a droopy hoisting crane and a similarly droopy steam calliope.

Geisel clearly enjoyed drawing architecturally elaborate objects, and many of his motifs can be traced to structures in his childhood home of Springfield, Massachusetts. These include the onion domes of its Main Street and elements reminiscent of his family's brewery. His endlessly varied yet never rectilinear palaces, ramps, platforms, and free-standing stairways are among his most imaginative and evocative creations. Geisel also delighted in designing complex imaginary machines, such as the "Audio-Telly-O-Tally-O-Count" from Dr. Seuss's Sleep Book, or the "most peculiar machine" belonging to Sylvester McMonkey McBean in The Sneetches. Furthermore, he was fond of illustrating outlandish arrangements of feathers or fur, as seen in the 500th hat of Bartholomew Cubbins, the elaborate tail of Gertrude McFuzz, and the pet for girls who enjoy brushing and combing in One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish.

Geisel's illustrations vividly convey motion. He frequently employed a distinctive "voilà" gesture, where a hand flips outward with fingers slightly spread backward and the thumb up. This gesture is performed by Ish in One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish (with fish performing it with their fins), during the introduction of various acts in If I Ran the Circus, and in the introduction of the "Little Cats" in The Cat in the Hat Comes Back. He also often drew hands with interlocked fingers, creating the appearance of characters twiddling their thumbs. Following the tradition of cartooning, Geisel used motion lines to illustrate movement, such as the sweeping lines accompanying Sneelock's final dive in If I Ran the Circus. Cartoon lines were also utilized to depict the action of the senses-sight, smell, and hearing-in The Big Brag, and even to illustrate "thought," as demonstrated when the Grinch conceives his infamous plan to ruin Christmas.

5. Personal Life

Theodor Seuss Geisel's personal life, while largely kept private, included significant events and relationships. He was married twice. His first marriage was to Helen Palmer. Helen experienced a long struggle with various illnesses. Tragically, on October 23, 1967, she died by suicide.

Less than a year later, on August 5, 1968, Geisel married Audrey Dimond. Reports suggested that he and Audrey had been involved in an affair prior to Helen's death. Despite dedicating a substantial portion of his life to creating literature for children, Theodor Geisel never had biological children of his own. He famously joked about his approach to children, stating, "You have 'em; I'll entertain 'em." Audrey Geisel later elaborated on his perspective, confirming that Geisel "lived his whole life without children and he was very happy without children." Audrey oversaw Geisel's literary estate until her death on December 19, 2018, at the age of 97.

6. Awards and Honors

Theodor Seuss Geisel received numerous accolades and recognitions throughout his distinguished career for his substantial contributions to literature and education.

He was awarded two Primetime Emmy Awards: one for Outstanding Children's Special for Halloween Is Grinch Night in 1978, and another for Outstanding Animated Program for The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat in 1982.

In 1980, Geisel received an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters (L.H.D.) from Whittier College. The same year, he was honored with the prestigious Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal from the professional children's librarians. This award recognized his "substantial and lasting contributions to children's literature" and was presented every five years at that time.

A pinnacle of his recognition came in 1984 when he was granted a special Pulitzer Prize. The citation commended his "contribution over nearly half a century to the education and enjoyment of America's children and their parents." His birthday, March 2, has since been adopted as the annual date for National Read Across America Day, an initiative promoting reading established by the National Education Association.

7. Death

Theodor Seuss Geisel died of cancer on September 24, 1991, at his home in the La Jolla community of San Diego, California. He was 87 years old. Following his passing, his ashes were scattered in the Pacific Ocean.

8. Legacy and Impact

Theodor Seuss Geisel's legacy extends far beyond his published works, encompassing various posthumous honors, ongoing critical discussions, and a profound influence on literature and education.

8.1. Posthumous Honors and Memorials

Four years after his death, on December 1, 1995, the University Library Building at the University of California, San Diego was renamed Geisel Library in honor of Geisel and his widow, Audrey, acknowledging their generous contributions to the library and their dedication to improving literacy. The library houses a significant collection of Geisel's original works, including drawings and notes.

In 2002, the Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden opened in his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts, featuring bronze sculptures of Geisel alongside many of his beloved characters. This was followed by the opening of the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum in 2017, located adjacent to the sculpture garden within the Springfield Museums Quadrangle. In 2008, Dr. Seuss was inducted into the California Hall of Fame.

To further honor his contributions to early reading, U.S. children's librarians established the annual Theodor Seuss Geisel Award in 2004. This award recognizes "the most distinguished American book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding year," emphasizing creativity and imagination to engage children from pre-kindergarten to second grade.

At Dartmouth College, Geisel's alma mater, incoming first-year students participate in pre-matriculation trips run by the Dartmouth Outing Club, where they famously enjoy green eggs and ham for breakfast at the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge. On April 4, 2012, Dartmouth Medical School was renamed the Audrey and Theodor Geisel School of Medicine, in recognition of the Geisels' long-standing generosity to the college. Additionally, Dr. Seuss has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, located at the 6500 block of Hollywood Boulevard. In 2012, a crater on the planet Mercury was named after Geisel.

8.2. Criticism and Controversies

Despite his widespread popularity, Theodor Seuss Geisel's legacy has been subject to increasing scrutiny, particularly concerning accusations of racist depictions and orientalism within his works. In 2017, when then-First Lady Melania Trump donated Seuss books to a school, a librarian controversially rejected them, citing that his illustrations were "steeped in racist propaganda and caricatures, and harmful stereotypes."

A significant academic paper from 2019, published in "Research on Diversity in Youth Literature," analyzed 50 of Geisel's works and reported that 43 out of 45 characters of color displayed Orientalist features. The study also highlighted his early career, noting the publication of anti-Black and anti-Semitic cartoons in the 1920s, and his creation of explicitly anti-Japanese propaganda during World War II, which contributed to the incitement of prejudice and the internment of Japanese Americans.

In 2021, on what would have been Geisel's 117th birthday, President Joe Biden notably omitted any mention of Dr. Seuss in his annual "Read Across America Day" proclamation, breaking a tradition upheld by previous administrations. This decision was largely seen as a response to the growing awareness of the problematic elements in some of Geisel's works. On the same day, Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced its decision to cease publication and licensing of six books-And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot's Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat's Quizzer. The organization cited that these books "portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong."

This move by Dr. Seuss Enterprises sparked a debate, with some conservative groups denouncing it as an example of "cancel culture." However, the conversation around literary appropriateness continued to evolve, demonstrating that such issues are not confined to a single political stance. For instance, in 2024, books by Dr. Seuss were among many withdrawn from school libraries in Tennessee due to a Republican-backed law, illustrating a complex and shifting landscape of content review across different political viewpoints.

8.3. Influence on Literature and Education

Dr. Seuss made profound and lasting contributions to children's literature and early education. His unique ability to combine imaginative storytelling with a simplified vocabulary revolutionized how children learned to read. His creation of the Beginner Books series, spurred by concerns about child illiteracy stemming from boring textbooks, directly addressed a critical need. Books like The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham proved that early readers could be both accessible and exciting, making reading an enjoyable adventure rather than a chore. This innovation not only captured the imaginations of millions of children but also provided a vital tool for educators, transforming literacy instruction in the United States and beyond.

His distinctive artistic style, characterized by whimsical creatures and non-linear architecture, and his innovative use of anapestic meter and invented words, created a world that was both fantastical and inviting. This blend of literary and visual artistry encouraged creativity and linguistic play, leaving an indelible mark on generations of readers and aspiring authors. His works also subtly introduced children to complex social and political themes, fostering early critical thinking and empathy.

9. Adaptations

For much of his career, Theodor Seuss Geisel was hesitant to allow his characters to be marketed outside of his books. However, he gradually eased this policy, particularly regarding animated cartoons, an art form in which he had gained experience during World War II.

The first adaptation of Geisel's work was an animated short film based on Horton Hatches the Egg, animated at Leon Schlesinger Productions in 1942 and directed by Bob Clampett. George Pal adapted two of Geisel's works into stop-motion films as part of his Puppetoons theatrical cartoon series for Paramount Pictures: The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1943) and And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1944), both of which were nominated for an Academy Award for "Short Subject (Cartoon)".

In 1966, Geisel authorized his friend and former wartime colleague, eminent cartoon artist Chuck Jones, to create a cartoon version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! This animated special, narrated by Boris Karloff (who also voiced the Grinch), is still a widely broadcast annual Christmas television special. Jones also directed an adaptation of Horton Hears a Who! in 1970 and produced an adaptation of The Cat in the Hat in 1971.

From 1972 to 1983, Geisel wrote six animated specials produced by DePatie-Freleng: The Lorax (1972), Dr. Seuss on the Loose (1973), The Hoober-Bloob Highway (1975), Halloween Is Grinch Night (1977), Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You? (1980), and The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat (1982). Several of these specials earned multiple Emmy Awards. A Soviet paint-on-glass-animated short film titled Welcome (1986) was an adaptation of Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose. The final adaptation of Geisel's work released before his death was The Butter Battle Book, a television special directed by Ralph Bakshi. After his passing, a television film titled In Search of Dr. Seuss was released in 1994, which adapted many of Seuss's stories.

After Geisel's death in 1991, his widow Audrey Geisel managed licensing matters until her passing in 2018, after which control transferred to the nonprofit Dr. Seuss Enterprises. Audrey approved a live-action feature film version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas starring Jim Carrey, as well as a Seuss-themed Broadway musical called Seussical, both of which premiered in 2000. In 2003, another live-action film adaptation, The Cat in the Hat, was released, featuring Mike Myers as the title character. Audrey Geisel was critical of this film, particularly Myers' casting, and stated that she would not permit any further live-action adaptations of Geisel's books.

However, animated adaptations continued. A first CGI feature film adaptation of Horton Hears a Who! was approved and released on March 14, 2008, to positive reviews. A second CGI-animated feature film adaptation of The Lorax was released by Universal Pictures on March 2, 2012, on what would have been Seuss's 108th birthday. The third CGI-animated feature film based on Seuss's work, The Grinch, was released by Universal Pictures on November 9, 2018.

Geisel's books and characters are also featured in Seuss Landing, one of the themed islands at the Islands of Adventure theme park in Orlando, Florida. In an effort to match Geisel's distinctive visual style, the area is reportedly designed without any straight lines. The Hollywood Reporter has reported that Warner Animation Group and Dr. Seuss Enterprises have reached a deal to produce new animated films based on Dr. Seuss's stories, with their first project being a fully animated version of The Cat in the Hat.

9.1. Theatrical Films

| Year | Title | Format | Director(s) | Screenwriter(s) | Distributor | Studio | Length | Budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | Horton Hatches the Egg | traditional animation | Bob Clampett | - | Warner Bros. Pictures | Leon Schlesinger Productions | 10 min | - |

| 1943 | The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins | stop motion | George Pal | - | Paramount Pictures | George Pal Productions | 10 min | - |

| 1944 | And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street | - | George Pal Productions | - | ||||

| 1950 | Gerald McBoing-Boing | traditional animation | Robert Cannon | - | UPA and Columbia Pictures | United Productions of America | 10 min | - |

| 1953 | The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. | live-action | Roy Rowland | Dr. Seuss and Allan Scott | Columbia Pictures | A Stanley Kramer Company Production | 92 min | 2.75 M USD |

| 2000 | How the Grinch Stole Christmas | Ron Howard | Jeffrey Price & Peter S. Seaman | Universal Pictures | Imagine Entertainment | 104 min | 123.00 M USD | |

| 2003 | The Cat in the Hat | Bo Welch | Alec Berg, David Mandel & Jeff Schaffer | Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures | 82 min | 109.00 M USD | ||

| 2008 | Horton Hears a Who! | computer animation | Jimmy Hayward & Steve Martino | Cinco Paul and Ken Daurio | 20th Century Fox | 20th Century Fox Animation Blue Sky Studios | 86 min | 85.00 M USD |

| 2012 | The Lorax | Chris Renaud and Kyle Balda | Universal Pictures | Illumination Entertainment | 70.00 M USD | |||

| 2018 | The Grinch | Scott Mosier and Yarrow Cheney | Michael LeSieur and Tommy Swerdlow | 90 min | 75.00 M USD | |||

| 2026 | The Cat in the Hat | Erica Rivinoja & Alessandro Carloni | Warner Bros. Pictures | Warner Bros. Pictures Animation | TBA | |||

| Thing One and Thing Two | TBA | |||||||

| 2028 | Oh, the Places You'll Go! | Jon M. Chu | TBA | |||||

9.2. Television Series and Specials

Five television series have been adapted from Geisel's work. The first, Gerald McBoing-Boing, was an animated television adaptation of Geisel's 1951 cartoon of the same name and aired for three months between 1956 and 1957. The second, The Wubbulous World of Dr. Seuss, was a mix of live-action and puppetry by Jim Henson Television, the producers of The Muppets. It aired for two seasons on Nickelodeon in the United States, from 1996 to 1998. The third, Gerald McBoing-Boing, is a remake of the 1956 series. Produced in Canada by Cookie Jar Entertainment (now DHX Media) and in North America by Classic Media (now DreamWorks Classics), it ran from 2005 to 2007. The fourth, The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That!, produced by Portfolio Entertainment Inc., began on August 7, 2010, in Canada and September 6, 2010, in the United States and continues to produce new episodes. The fifth, Green Eggs and Ham, is an animated streaming television adaptation of Geisel's 1960 book of the same title and premiered on November 8, 2019, on Netflix. A second season, titled Green Eggs and Ham: The Second Serving, premiered in 2022.

| Year | Title | Format | Studio | Director | Writer | Distributor | Length | Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | How the Grinch Stole Christmas! | traditional animation | Chuck Jones Productions | Chuck Jones | Dr. Seuss, Irv Spector, and Bob Ogle | MGM | 25 min | CBS |

| 1970 | Horton Hears a Who! | Dr. Seuss | ||||||

| 1971 | The Cat in the Hat | DePatie-Freleng Enterprises | Hawley Pratt | CBS | ||||

| 1972 | The Lorax | |||||||

| 1973 | Dr. Seuss on the Loose | |||||||

| 1975 | The Hoober-Bloob Highway | Alan Zaslove | ||||||

| 1977 | Halloween Is Grinch Night | Gerard Baldwin | ABC | ABC | ||||

| 1980 | Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You? | |||||||

| 1982 | The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat | Bill Perez | ||||||

| 1989 | The Butter Battle Book | Bakshi Production | Ralph Bakshi | Turner | TNT | |||

| 1995 | Daisy-Head Mayzie | Hanna-Barbera Productions | Tony Collingwood |

| Year | Title | Format | Director | Writer | Studio | Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996-1998 | The Wubbulous World of Dr. Seuss | live-action/puppet | Various | Various | Jim Henson Productions | Nickelodeon |

| 2010-2018 | The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That! | traditional animation | Collingwood O'Hare Productions Portfolio Entertainment Random House Children's Entertainment KQED | Treehouse TV | ||

| 2019-2022 | Green Eggs and Ham | Gulfstream Pictures A Stern Talking To A Very Good Production Warner Bros. Animation | Netflix |

10. Bibliography

Theodor Seuss Geisel wrote and illustrated more than 60 books throughout his long career. Most of these were published under his renowned pseudonym, Dr. Seuss, but he also authored over a dozen books as Theo LeSieg and one as Rosetta Stone. His books have consistently topped bestseller lists, collectively selling over 600 million copies and being translated into more than 20 languages.

In 2000, Publishers Weekly compiled a list of the best-selling children's books of all time. Out of the top 100 hardcover titles, 16 were written by Geisel, including Green Eggs and Ham at number 4, The Cat in the Hat at number 9, and One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish at number 13. Even in the years following his death in 1991, additional books were published based on his sketches and notes, such as Hooray for Diffendoofer Day! and Daisy-Head Mayzie. My Many Colored Days, originally written in 1973, was posthumously published in 1996. In September 2011, a collection of seven stories originally published in magazines during the 1950s was released under the title The Bippolo Seed and Other Lost Stories.

10.1. Selected titles

- And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937)

- Horton Hatches the Egg (1940)

- Horton Hears a Who! (1954)

- The Cat in the Hat (1957)

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957)

- The Cat in the Hat Comes Back (1958)

- One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish (1960)

- Green Eggs and Ham (1960)

- The Sneetches and Other Stories (1961)

- Hop on Pop (1963)

- Fox in Socks (1965)

- The Lorax (1971)

- The Butter Battle Book (1981)

- I Am Not Going to Get Up Today! (1987)

- Oh, the Places You'll Go! (1990)