1. Overview

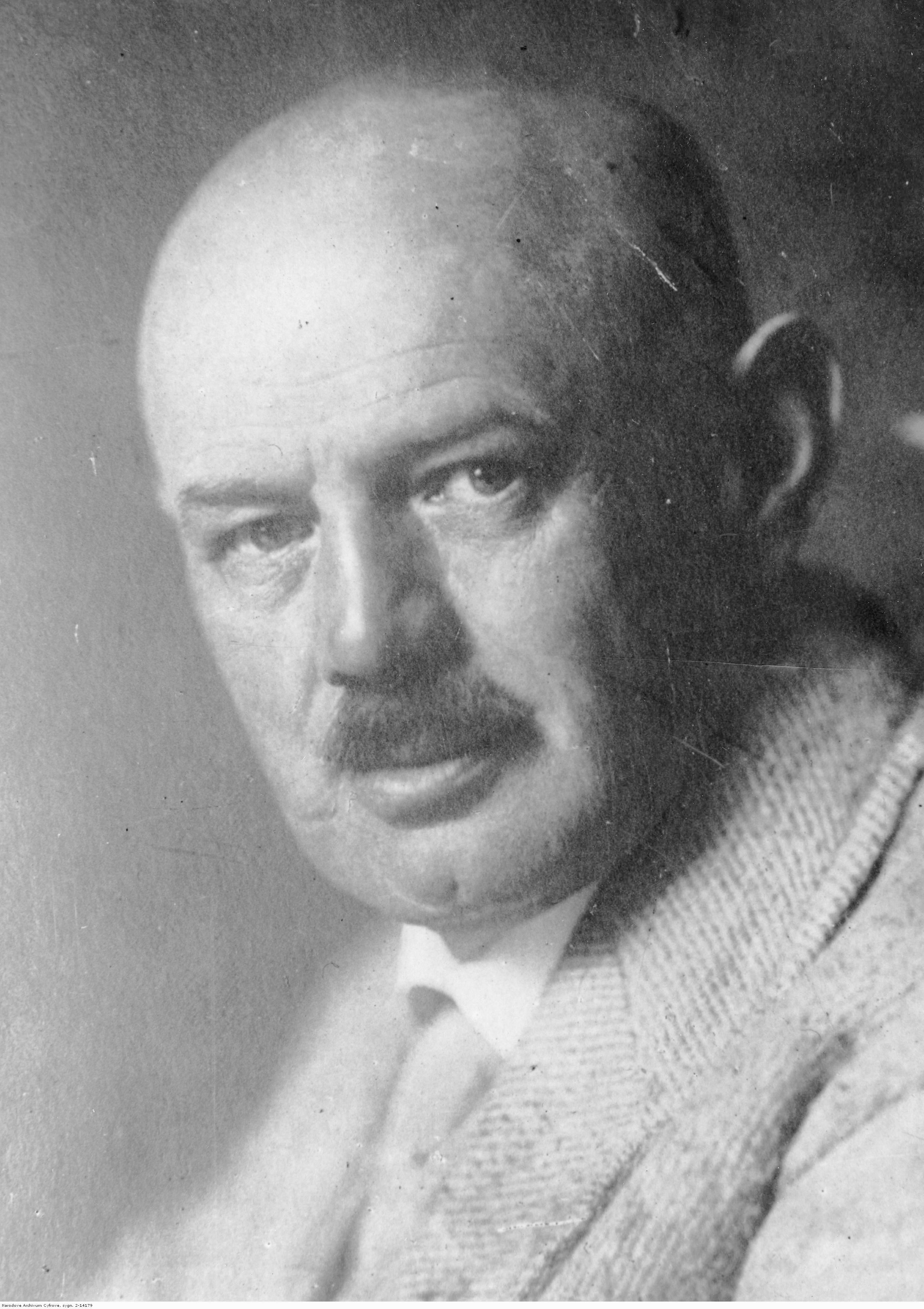

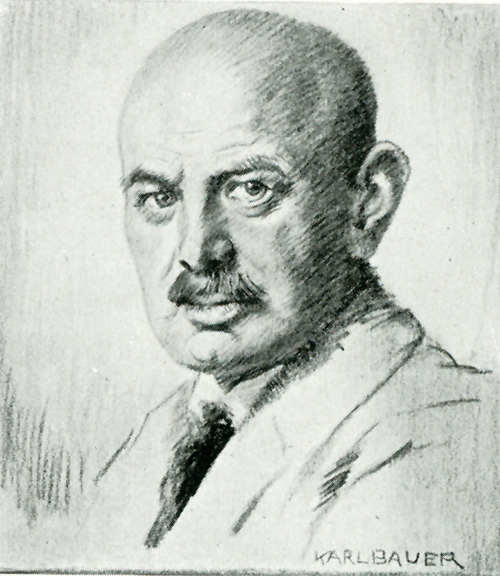

Dietrich Eckart was a prominent German journalist, playwright, poet, and political activist who played a foundational role in the early stages of the Nazi Party. Born in Bavaria, Eckart initially pursued studies in law and medicine before dedicating himself to a career in arts and journalism in Berlin. His literary work, particularly his nationalist and antisemitic adaptation of Henrik Ibsen's Peer Gynt, gained him significant recognition and provided him with social connections that proved crucial for the nascent Nazi movement.

Eckart's political thought was deeply rooted in völkisch ideology and virulent antisemitism. He was instrumental in the formation of the German Workers' Party (DAP), the precursor to the Nazi Party, and became the first editor and publisher of its official newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter. He also authored the lyrics for the party's first anthem, "Sturmlied", and coined the influential slogan "Deutschland erwache" ("Germany awake").

His most significant impact, however, lay in his profound mentorship of Adolf Hitler during the early 1920s. Eckart acted as a father figure and intellectual guide, shaping Hitler's core beliefs, introducing him to influential circles, and promoting the concept of Hitler as a "German Messiah." This mentorship was crucial in constructing the "Hitler Myth," a central element of Nazi propaganda that presented Hitler as a divinely chosen leader. Eckart participated in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, was briefly imprisoned, and died shortly after his release due to illness. Following the establishment of Nazi Germany in 1933, Eckart was posthumously elevated to the status of a major ideologue and national hero, acknowledged by Hitler as the spiritual co-founder of Nazism. However, historical assessments critically analyze his role, highlighting the destructive social and political consequences of his antisemitic, anti-democratic, and nationalist ideologies, which significantly contributed to the foundational tenets of Nazism.

2. Early Life and Education

Dietrich Eckart was born on March 23, 1868, in Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, a town located about 20 mile (32 km) southeast of Nuremberg in the Kingdom of Bavaria. His father, Christian Eckart, was a royal notary and lawyer, while his mother, Anna, was a devout Catholic. Tragedy struck Eckart early in life when his mother passed away when he was only ten years old. He subsequently faced disciplinary issues, leading to his expulsion from several schools. In 1895, his father died, leaving him a substantial inheritance, which Eckart quickly squandered.

Eckart initially pursued legal studies at the University of Erlangen before shifting to medicine at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. During his university years, he was an enthusiastic member of German Student Corps, participating in fencing and drinking activities. In 1891, he decided to abandon his academic pursuits to become a poet, playwright, and journalist. By 1899, diagnosed with morphine addiction and facing severe financial hardship, he relocated to Berlin. There, he wrote numerous plays, often drawing on autobiographical elements, and became a protégé of Count Georg von Hülsen-Haeseler (1858-1922), the artistic director of the Prussian Royal Theatre. Following a duel, Eckart was briefly incarcerated at Veste Oberhaus in Passau.

In 1907, Eckart resided with his brother Wilhelm in the Döberitz mansion colony, west of Berlin. He married Rose Marx, a wealthy widow from Bad Blankenburg, in 1913 and subsequently returned to Munich.

3. Literary and Media Career

Dietrich Eckart established himself as a poet, playwright, and journalist, achieving notable success in the theatrical world. His 1912 adaptation of Henrik Ibsen's classic play, Peer Gynt, proved to be a significant triumph, running for over 600 performances in Berlin alone. Eckart's version transformed Ibsen's original into a powerful dramatization infused with nationalist and antisemitic ideas. In his adaptation, Peer Gynt was reimagined as a superior Germanic hero, whose struggles against the "trolls" were presented as a fight against implicitly Jewish influences. While Ibsen's original depicted Gynt's selfish actions leading to his ruin and a shameful return, Eckart portrayed Gynt as a noble figure whose transgressions were justified, ultimately returning to reclaim his youthful innocence. This interpretation was heavily influenced by Eckart's admiration for the philosopher Otto Weininger, leading him to view Gynt as an antisemitic genius, with the "trolls" and "Dovre Giant" representing Weininger's concept of "Jewishness."

Despite this singular success, Eckart never achieved similar theatrical acclaim again, a failure he attributed to the pervasive influence of Jews in German culture. Nevertheless, the financial gains and social connections from Peer Gynt proved invaluable, enabling him to later introduce Adolf Hitler to numerous influential German citizens, a pivotal factor in Hitler's ascent to power.

Eckart also developed an ideology of a "genius superman," drawing inspiration from the writings of Völkisch author Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels and the philosopher Otto Weininger. He saw himself as a successor to figures like Heinrich Heine, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Angelus Silesius, and was particularly fascinated by the Buddhist concept of Maya, or illusion.

As a publicist, Eckart founded, published, and edited the antisemitic weekly Auf gut Deutsch ("In Plain German") in December 1918, with financial backing from the Thule Society. He collaborated with Alfred Rosenberg, whom he called his "co-warrior against Jerusalem," and Gottfried Feder. A staunch critic of the German Revolution and the Weimar Republic, Eckart vehemently opposed the Treaty of Versailles, which he condemned as treasonous. He was a fervent proponent of the stab-in-the-back legend (Dolchstoßlegende), which falsely blamed Social Democrats and Jews for Germany's defeat in World War I.

4. Ideology and Political Activism

Dietrich Eckart's political thought was characterized by a fervent embrace of völkisch ideology and virulent antisemitism, which he actively disseminated through his writings and political activities. His crucial role in the formation of early Nazi organizations solidified his position as a key figure in the nascent movement. Eckart was also known for borrowing the term "Third Reich" (Das Dritte Reich) from conservative revolutionary thinker Arthur Moeller van den Bruck.

4.1. Völkisch Ideology and Antisemitism

Eckart's worldview was shaped by various intellectual influences, notably Otto Weininger and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, whose ideas contributed to his conversion to radical antisemitism. While he was not always an antisemite-having written a poem in 1898 praising a Jewish girl and initially admiring Jewish figures like Heinrich Heine and Otto Weininger-his later views became extreme. Weininger, a Jewish philosopher who converted to Protestantism and espoused self-hating Jewish views, may have influenced Eckart's shift towards antisemitism.

A significant catalyst for Eckart's antisemitism was the publication of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fabricated text brought to Germany by "white Russian" émigrés fleeing the October Revolution. This book, which purported to outline an international Jewish conspiracy for world domination, was widely believed by many right-wing and völkisch political figures, including Eckart.

Eckart's antisemitism was deeply ingrained and extreme. He expressed the opinion that all Jews should be put on a train and driven into the Red Sea. He also advocated for severe penalties against Jews, proposing that any Jew who married a German woman should be jailed for three years, and executed if the "crime" was repeated. Paradoxically, Eckart also believed in a symbiotic relationship between Aryans and Jews, suggesting that humanity's existence depended on this antithesis and that "the end of all times" would come "if the Jewish people perished."

He viewed World War I not as a conflict between Germans and non-Germans, but as a "holy war" between Aryans and Jews, whom he believed conspired to bring about the downfall of the Russian and German empires. To describe this apocalyptic struggle, Eckart extensively drew imagery from the legends of Ragnarök and the Book of Revelation.

4.2. Founding of the German Workers' Party (DAP) and Nazi Party

Dietrich Eckart played a foundational role in the establishment of the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German Workers' Party, or DAP) in January 1919, alongside Anton Drexler, Gottfried Feder, and Karl Harrer. This party would later transform into the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), more commonly known as the Nazi Party, in February 1920, a change made to broaden its appeal.

Eckart was instrumental in the party's acquisition of the Münchener Beobachter newspaper in December 1920. He arranged a loan of 60.00 K DEM from German Army funds, made available by General Franz Ritter von Epp. Eckart's own house and possessions served as collateral for the loan, with Dr. Gottfried Grandel, an Augsburg chemist and factory owner who was a friend and party funder, acting as guarantor. The newspaper was subsequently renamed the Völkischer Beobachter ("Folkist Observer") and became the official organ of the Nazi Party, with Eckart serving as its first editor and publisher.

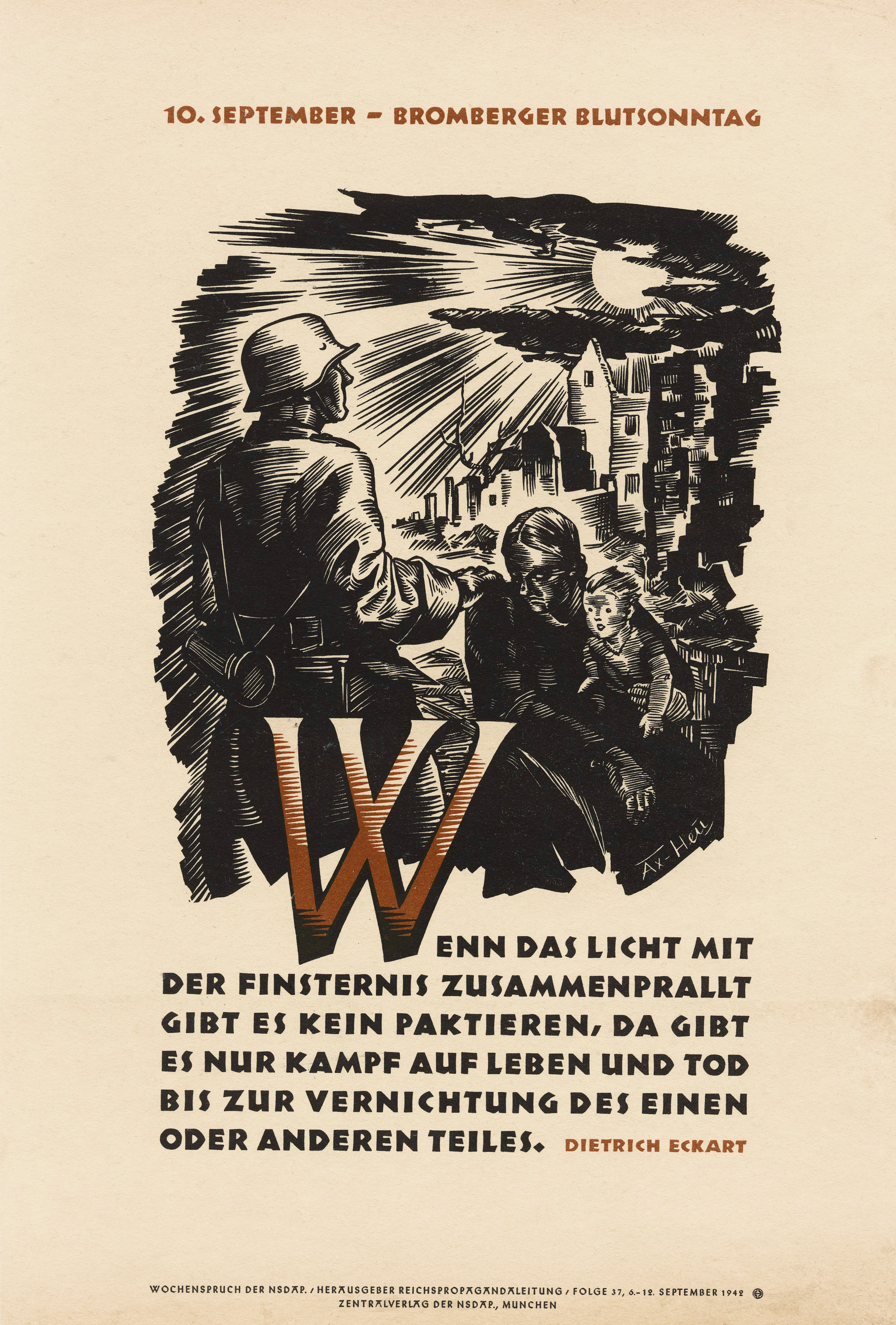

Beyond his publishing activities, Eckart was a key propagandist for the early Nazi movement. He coined the influential Nazi slogan "Deutschland erwache" ("Germany awake") and wrote the lyrics for the anthem based on it, the "Sturm-Lied" ("Storming Song"). His efforts contributed significantly to shaping the party's early propaganda and ideological messaging.

In 1921, Eckart publicly offered 1.00 K DEM to anyone who could name a Jewish family whose sons had served more than three weeks at the front during World War I. Rabbi Samuel Freund of Hanover successfully named 20 Jewish families who met this condition and sued Eckart when he refused to pay. During the trial, Freund further provided names of 50 more Jewish families, some with up to seven veterans, and several of whom had lost up to three sons in the war. Eckart ultimately lost the case and was compelled to pay the reward.

5. Relationship with Adolf Hitler

The relationship between Dietrich Eckart and Adolf Hitler was profound and complex, with Eckart serving as a crucial mentor and intellectual catalyst for Hitler's political ascent and the development of core Nazi ideology. Their bond was not merely political but also deeply emotional and intellectual, described by some historians as almost symbiotic.

5.1. Early Encounters and Mentorship

Eckart first encountered Hitler when the latter delivered a speech to the German Workers' Party (DAP) membership in the winter of 1919. Hitler immediately impressed Eckart, who recognized his potential, stating, "I felt myself attracted by his whole way of being, and very soon I realized that he was exactly the right man for our young movement." While it is likely a Nazi legend, Eckart is famously quoted as having said about Hitler on their first meeting, "That's Germany's next great man - one day the whole world will talk about him."

Being 21 years older than Hitler, Eckart assumed a paternal role for a group of younger völkisch men, including Hitler and Hermann Esser. He often mediated conflicts between Hitler and Esser, affirming Hitler's superiority as the DAP's most effective speaker. Eckart became Hitler's primary mentor, engaging in extensive intellectual exchanges that helped solidify the party's theories and beliefs. He provided practical support, lending Hitler books, giving him a trench coat, and correcting his speaking and writing style. Hitler later admitted, "Stylistically I was still an infant." Eckart also tutored the provincial Hitler in proper manners, viewing him as his protégé.

Hitler and Eckart shared many commonalities, including their interest in art and politics, their self-perception as artists, and a shared propensity for depression. Both also had early Jewish influences, a fact they preferred not to discuss. While Eckart, unlike Hitler, did not initially believe Jews were a separate race, by the time they met, Hitler's goal was "the total removal of the Jews." Eckart himself had expressed extreme antisemitic views, suggesting that all Jews should be put on a train and driven into the Red Sea, and advocating for imprisonment or execution for Jews who married German women. Despite these views, Eckart paradoxically believed that the existence of humanity depended on the antithesis between Aryans and Jews, writing in 1919 that it would be "the end of all times... if the Jewish people perished."

Eckart facilitated Hitler's entry into the Munich arts scene, introducing him to painter Max Zaeper and his salon of antisemitic artists, as well as to photographer Heinrich Hoffmann. He also introduced Alfred Rosenberg to Hitler, and between 1920 and 1923, Eckart and Rosenberg worked tirelessly for Hitler and the party. Through Rosenberg, Hitler was exposed to the writings of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. Both Eckart and Rosenberg significantly influenced Hitler's views on Russia, with Eckart seeing Russia as Germany's natural ally against the "current Jewish regime" (meaning the Bolsheviks). They provided the intellectual foundation for Hitler's Eastern policy, which was later put into practice by Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter.

In March 1920, at the request of Karl Mayr, the German General Staff officer who first introduced Hitler to politics, Hitler and Eckart flew to Berlin to meet Wolfgang Kapp and participate in the Kapp Putsch, aiming to connect Kapp's forces with Mayr. Although Kapp had previously donated 1.00 K DEM to Eckart's weekly magazine, the trip was unsuccessful. Hitler, wearing a false beard, suffered from airsickness on his first airplane flight, and the putsch was already collapsing upon their arrival. Captain Waldemar Pabst reportedly remarked, "The way you look and talk - people are going to laugh at you."

Eckart introduced Hitler to wealthy potential donors within the völkisch movement. While their fundraising efforts in Munich were not highly successful, they raised considerable funds in Berlin, where Eckart had better connections with the rich and powerful, including senior officials of the Pan-German League. During one of their frequent trips to the capital, Eckart introduced Hitler to socialite Helene Bechstein, who would become Hitler's future etiquette tutor, facilitating his entry into Berlin's upper class.

In June 1921, during a fundraising trip to Berlin by Hitler and Eckart, a mutiny erupted within the Nazi Party in Munich, with executive committee members seeking to merge with the rival German Socialist Party (DSP). Hitler returned to Munich on July 11 and angrily resigned. Recognizing that the loss of their leading public figure would mean the end of the party, the leadership, at Eckart's urging, asked him to negotiate Hitler's return. Hitler agreed to rejoin on the conditions that the party headquarters remain in Munich and that he replace Anton Drexler as party chairman, becoming the party's "Fuhrer" (dictator). The committee accepted, and Hitler rejoined on July 26, 1921.

Eckart also advised Hitler on individuals surrounding him and the party, such as the virulently antisemitic Julius Streicher, publisher of the quasi-pornographic Der Stürmer. Despite Hitler's aversion to pornography and disapproval of Streicher's sexual activities and his tendency to incite intra-party conflicts, Eckart reportedly told Hitler on multiple occasions that "one could not hope for a triumph of National Socialism without giving one's support to a man like Streicher." For a time, before Alfred Rosenberg assumed the role, Eckart, along with Gottfried Feder, was considered the Nazi Party's "philosopher."

5.2. Ideological Influence and the "Hitler Myth"

Eckart's influence on Hitler was profound, particularly in shaping his core beliefs and promoting the concept of a "German Messiah" who would lead the nation. Eckart's hero, Otto Weininger, had posited a dichotomy between genius and Jews, with genius representing masculinity and non-materialism, and Jews embodying pure femininity. Eckart adopted this philosophy, believing that the role of a genius was to liberate the world from the detrimental influence of Jews. This resonated with a segment of German society seeking a savior, a "German Messiah," to rescue them from the economic and political turmoil caused by the Great Depression and the economic repercussions of the Treaty of Versailles.

Under Eckart's guidance, Hitler began to perceive himself as this destined figure, a superior being. However, because geniuses were generally believed to be born, not made, Hitler could not publicly acknowledge the mentorship he received from Eckart and others. Consequently, in Mein Kampf, Hitler omitted any mention of Eckart, Karl Mayr, or other individuals who were instrumental in cultivating the image of Adolf Hitler as a natural genius and the German Messiah.

Shortly after the Nazi Party acquired the Völkischer Beobachter in December 1920, and Eckart was installed as editor with Rosenberg as his assistant, the two men began to use the newspaper as a vehicle to disseminate the "Hitler Myth." This narrative portrayed Hitler not merely as the leader of the Nazi Party but as a superior being, a divine German Messiah-the chosen one. The newspaper referred to him as "Germany's leader," and other Bavarian newspapers began to call him "the Bavarian Mussolini." This idea of Hitler's unique destiny spread, leading the Traunsteiner Wochenblatt newspaper to foresee, by November 1922, a time when "the masses of the people will raise [Hitler] up as their leader, and give him their allegiance through thick and thin."

Eckart also counseled Hitler that in his quest to be the "German Messiah," the ends justified the means. He advised Hitler not to be concerned about employing violence or transgressing societal norms, assuring him that, like Peer Gynt in his play, he would be forgiven for his "sins." In his introduction to the play, Eckart wrote that "German nature, which means, in the broader sense, the capability of self-sacrifice itself, that the world will heal, and find its way back to the pure divine, but only after a bloody war of annihilation against the united army of the 'trolls'; in other words, against the Midgard Serpent encircling the earth, the reptilian incarnation of the lie."

As Hitler gained more self-confidence, largely due to Eckart's mentorship, his reliance on Eckart as a mentor diminished, leading to a cooling of their relationship. In November 1922, Eckart and Emil Gansser, the party's chief fund-raiser outside Germany, traveled to Zurich, Switzerland, to meet Alfred Schwarzenbach, a wealthy silk entrepreneur. This trip, arranged by Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess, was followed by a repeat visit the next year, with Hitler also present. However, this second trip was a failure. Hitler's speech to German expatriates, right-wing Swiss officers, and Swiss businessmen, as well as the subsequent private meeting, proved to be a fiasco. Hitler attributed the failure to Eckart's lack of social graces.

In early 1923, after publishing a defamatory poem about then-German President Friedrich Ebert, Eckart evaded an arrest warrant by fleeing to the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgaden, close to the German-Austrian border, using the alias "Dr. Hoffman." In April, Hitler visited him at the Pension Moritz in Obersalzberg, staying for a few days under the name "Herr Wolf." This visit marked Hitler's first introduction to the area where he would later establish his mountain retreat, the Berghof.

Hitler had recently replaced Eckart as the publisher of the Völkischer Beobachter with Alfred Rosenberg, though he softened the blow by emphasizing his continued high regard for Eckart. Hitler stated that Eckart's "accomplishments are everlasting!" but that he was not constitutionally suited to run a large daily newspaper. Despite this, tensions began to surface between them, not only over personal disagreements but also due to Hitler's annoyance that Eckart doubted the possibility of a successful national revolution launched from Munich. Eckart famously argued, "Munich is not Berlin. It would lead to nothing but ultimate failure."

Despite his own role in promoting Hitler as a genius and messiah, Eckart complained to Ernst Hanfstaengl, another of Hitler's mentors, in May 1923, that Hitler exhibited "megalomania halfway between a Messiah complex and Neroism" after Hitler compared himself to Jesus expelling money-changers from the temple. Motivated by his temporary frustration with Eckart and Eckart's impracticality in operational matters, Hitler began attempting to manage the party without Eckart's assistance. When forced to rely on Eckart again as a political operative, the results were disappointing. Hitler started to view Eckart as a political liability due to his disorganization and increasing alcohol consumption. Nevertheless, Hitler did not discard or sideline him, as he had done with other early comrades who had obstructed his path. He remained intellectually and emotionally close to Eckart, continuing to visit him in the mountains, underscoring that their relationship extended beyond mere politics.

6. Political Participation and Death

On November 9, 1923, Dietrich Eckart actively participated in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich, a pivotal event in the early history of the Nazi Party. Following the collapse of the putsch, he was arrested along with Hitler and other prominent party officials. Eckart was subsequently incarcerated in Landsberg Prison. However, due to his deteriorating health, he was released shortly after his imprisonment.

Upon his release, Eckart traveled to Berchtesgaden to recuperate. He died there on December 26, 1923, at the age of 55, from a heart attack. He was buried in Berchtesgaden's old cemetery, in close proximity to the future graves of Nazi Party official Hans Lammers and his family.

Although Adolf Hitler did not mention Eckart in the first volume of his autobiographical manifesto, Mein Kampf, he dedicated the second volume to him after Eckart's death. In this dedication, Hitler wrote that Eckart was "one of the best, who devoted his life to the awakening of our people, in his writings and his thoughts and finally in his deeds." In private, Hitler consistently acknowledged Eckart's role as his mentor and teacher. In 1942, Hitler remarked, "We have all moved forward since then, that's why we don't see what [Eckart] used to be back then: a polar star. The writings of all others were filled with platitudes, but if he told you off: such wit! I was a mere infant then in terms of style." Hitler later confided to one of his secretaries that his friendship with Eckart was "one of the best things he experienced in the 1920s" and that he never again found a friend with whom he felt such "a harmony of thinking and feeling."

7. Ideas and Assessments

Dietrich Eckart is widely regarded as a significant ideological precursor to Nazism, with Hitler himself acknowledging him as its spiritual co-founder. His ideas were deeply rooted in a radical, antisemitic, and nationalist worldview that contributed fundamentally to the tenets of the Nazi movement.

7.1. Posthumous Recognition and Nazi Era Status

During the Nazi period, Dietrich Eckart was posthumously elevated to the status of a national hero and an ideological precursor, with numerous monuments and memorials established in his honor to solidify his symbolic importance. When the Waldbühne (Forest Stage) near the Olympic Stadium in Berlin was opened for the 1936 Summer Olympics, Hitler named it the "Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne" (Dietrich Eckart Theatre). The 5th Standarte (regiment) of the SS-Totenkopfverbände was granted the honor-title Dietrich Eckart. In 1937, the Realprogymnasium in Emmendingen was expanded and renamed the "Dietrich-Eckart secondary school for boys." Several new roads were also named after Eckart. All of these names were subsequently changed after the fall of the Nazi regime.

Eckart's birthplace, Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, was officially renamed with the added suffix "Dietrich-Eckart-Stadt" during the Nazi era. In 1934, Adolf Hitler personally inaugurated a monument in Eckart's honor in the city park. This monument has since been rededicated to Christopher of Bavaria (1416-1448), King of Denmark, who is believed to have been born in the town.

In March 1938, when Passau commemorated Eckart's 70th birthday at Veste Oberhaus Castle, the Lord Mayor announced the creation of a Dietrich-Eckart-Foundation and the restoration of the room where Eckart had been imprisoned. Additionally, a street in Passau was dedicated to Eckart.

7.2. Historical Assessments and Criticisms

Dietrich Eckart is widely considered the spiritual father of Nazism, a designation affirmed by Hitler himself, who acknowledged Eckart as the movement's spiritual co-founder. His ideas and influence played a critical role in shaping the early Nazi ideology, particularly its virulent antisemitism and anti-democratic stance.

Eckart's interpretation of World War I as a "holy war" between Aryans and Jews, rather than a conventional conflict, highlights the extreme nature of his racial theories. He believed that Jews were plotting the downfall of empires and used apocalyptic imagery from Ragnarök and the Book of Revelation to describe this perceived struggle. This perspective laid a pseudo-religious foundation for the Nazi regime's later genocidal policies.

In 1925, Eckart's unfinished essay, Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin: Zwiegespräch zwischen Hitler und mir ("Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin: Dialogue Between Hitler and Me"), was published posthumously. While some historians, like Margarete Plewnia, view the dialogue as Eckart's own invention, others, including Ernst Nolte, Friedrich Heer, and Klaus Scholder, believe it reflects Hitler's actual words, as it was completed and published by Alfred Rosenberg using Eckart's notes. Historian Richard Steigmann-Gall considered the book a reliable indicator of Eckart's views. Steigmann-Gall quoted from the book, "In Christ, the embodiment of all manliness, we find all that we need. And if we occasionally speak of Baldur (a god in Norse mythology), our words always contain some joy, some satisfaction, that our pagan ancestors were already so Christian as to have an indication of Christ in this ideal figure." Steigmann-Gall concluded that Eckart, far from advocating paganism or anti-Christian religion, saw Christ as a leader to be emulated in Germany's post-war turmoil. However, historian Ernst Piper dismissed Steigmann-Gall's views on a positive relationship between early NSDAP members' admiration for Christ and Christianity. Eckart fiercely opposed the political Catholicism of the Bavarian People's Party and its national ally, the Centre Party, instead supporting a vaguely defined "positive Christianity." Through the pages of Völkischer Beobachter, Eckart attempted to win over Bavarian Catholics to the Nazi cause, but this effort ultimately failed with the Beer Hall Putsch, which put the Nazis at odds with Bavarian Catholics. Joseph Howard Tyson notes that Eckart's anti-Old Testament views bear a strong resemblance to the early Christian heresy of Marcionism.

In 1935, Alfred Rosenberg published Dietrich Eckart. Ein Vermächtnis ("Dietrich Eckart. A Legacy"), a collection of Eckart's writings. This work includes passages that further illuminate Eckart's views on genius, spirituality, and his stark contrast between what he perceived as "true genius" (associated with Christ) and the "race" of Heinrich Heine (associated with Jewishness). He wrote: "To be a genius means to use the soul, to strive for the divine, to escape from the mean; and even if this cannot be totally achieved, there will be no space for the opposite of good. It does not prevent the genius to portray also the wretchedness of being in all shapes and colors, being the great artist that he is; but he does this as an observer, not taking part, sine ira et studio, his heart remains pure. ... The ideal in this, just like in every respect whatsoever is Christ; his words 'You judge by human standards; I pass judgment on no one' show the completely divine freedom from the influence of the senses, the overcoming of the earthly world even without art as an intermediary. At the other end you find Heinrich Heine and his race ... all they do culminates in ... the motive, in subjugating the world, and the less this works, the more hate-filled their work becomes that is to satisfy their motive, the more deceitful and fallacious every try to reach the goal. No trace of true genius, the very opposite of the manliness of genius..." This passage underscores Eckart's profound antisemitism, intertwining it with his twisted notions of artistic genius and spiritual purity, ultimately serving to dehumanize Jewish people and justify their persecution.

Various contemporaries and historians have offered assessments of Eckart's personality and character. Early Nazi adherent Ernst Hanfstaengl described Eckart as "a perfect example of an old-fashioned Bavarian with the appearance of a walrus." Journalist Edgar Ansel Mowrer characterized him as "a strange drunken genius." Historian Samuel W. Mitcham called Eckart an "eccentric intellectual" and "extreme antisemite" who was also a "man of the world" fond of "wine, women, and pleasures of the flesh." Alan Bullock depicted Eckart as having "violent nationalist, anti-democratic, and anti-clerical opinions, a racist with an enthusiasm for Nordic folklore and a taste for Jew-baiting" who "talked well even when he was drunk" and "knew everyone in Munich." Richard J. Evans noted that Eckart, a "failed racist poet and dramatist," attributed his career failures to Jewish dominance in German culture, defining anything subversive or materialistic as "Jewish." Joachim C. Fest described Eckart as a "roughhewn and comical figure, with [a] thick round head, [and a] partiality for good wine and crude talk" with a "bluff and uncomplicated manner." His revolutionary goals included promoting "true socialism" and freeing the country from "interest slavery." Thomas Weber characterized Eckart as having a "jovial but moody nature," while John Toland described him as "an original raffish man with a touch of genius," a "tall, bald, burly eccentric who spent much of his time in cafes and beer halls giving equal attention to drink and talk." Toland further elaborated that Eckart was "a born romantic revolutionary... a master of coffeehouse polemics. A sentimental cynic, a sincere charlatan, constantly on stage, lecturing brilliantly if given the slightest opportunity be it at his own apartment, on the street or in a café." These descriptions collectively paint a picture of a complex, charismatic, yet deeply prejudiced individual whose personal traits and intellectual leanings made him a potent force in the early Nazi movement.

8. Works

Dietrich Eckart's literary and political writings reflect his deeply ingrained nationalist and antisemitic ideologies, serving as significant contributions to the intellectual foundation of early Nazism. His most notable work is the posthumously published essay:

- Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin: A Dialogue Between Adolf Hitler and Me (Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin: Zwiegespräch zwischen Hitler und mir). This unfinished essay, published in 1925, purports to be a dialogue between Eckart and Hitler, detailing their shared views on the nature of Bolshevism as a Jewish conspiracy. It provides crucial insight into the ideological framework that would underpin the Nazi movement, particularly its virulent anti-communism intertwined with antisemitism.

- [http://www.jrbooksonline.com/PDF_Books/Bolshevism_From_Moses_to_Lenin.pdf English translation (PDF)]

- [http://nsl-archiv.com/Buecher/Bis-1945/Eckart,%20Dietrich%20-%20Der%20Bolschewismus%20von%20Moses%20bis%20Lenin%20(1924,%2057%20S.,%20Scan).pdf German original (PDF)]