1. Overview

Richard Hirschfeld Williams (May 7, 1929 - July 7, 2011), widely known as Dick Williams, was a prominent American figure in Major League Baseball (MLB), serving as a left fielder, third baseman, manager, coach, and front-office consultant. He was particularly recognized for his demanding and outspoken managerial style from 1967 to 1969 and again from 1971 to 1988. Throughout his career, Williams led his teams to three American League pennants, one National League pennant, and secured two World Series championships. He stands as one of only nine managers to achieve pennants in both major leagues and, along with Bill McKechnie and later Bruce Bochy, is one of only three managers to guide three different franchises to the World Series. Furthermore, he and Lou Piniella are the sole managers in history to lead four teams to seasons with 90 or more wins. Williams was celebrated for his significant contributions to the sport with his induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2008, following his election by the Veterans Committee. His career was marked by both remarkable successes and notable controversies, including legal issues that impacted his Hall of Fame consideration, and a personal life that included a brief stint as an actor.

2. Early Life and Background

Dick Williams was born on May 7, 1929, in St. Louis, Missouri. He spent his early childhood there until the age of 13, when his family relocated to Pasadena, California. In Pasadena, he attended Pasadena High School before continuing his education at Pasadena City College.

3. Playing Career

Williams began his professional baseball journey by signing his first contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. He made his major league debut with the Dodgers in 1951. A right-handed batter and thrower, Williams was listed at 6 ft tall and 190 lb (190 lb). He initially played as an outfielder, but on August 25, 1952, he suffered a shoulder separation while attempting a diving catch, which permanently weakened his throwing arm. This injury led him to adapt and learn to play multiple positions, frequently appearing as a first baseman and third baseman. To maintain his presence in the major leagues, he became known as a notorious "bench jockey".

Over his 13-season playing career, Williams appeared in 1,023 games. He played for several MLB teams, including the Brooklyn Dodgers, Baltimore Orioles, Cleveland Indians, Kansas City Athletics, and Boston Red Sox. He finished his playing career with a batting average of .260, accumulating 768 hits, which included 70 home runs, 157 doubles, and 12 triples. Defensively, he played in 456 games in the outfield, 257 at third base, and 188 at first base.

Williams was a favorite of Paul Richards, who acquired him four different times between 1956 and 1962 while serving as a manager or general manager for the Orioles and the Houston Colt .45s. One notable transaction occurred on April 12, 1961, when Williams was traded from the Athletics to the Orioles alongside Dick Hall in exchange for Chuck Essegian and Jerry Walker. Although he was acquired by Houston in an off-season "paper transaction" on October 12, 1962, he never played for the team, being traded to the Red Sox for outfielder Carroll Hardy on December 10 of the same year.

His two-year playing stint with the Boston Red Sox was largely uneventful, with one exception. On June 27, 1963, at Fenway Park, Williams hit a long drive that was caught by Cleveland right fielder Al Luplow in what is considered one of the greatest catches in the park's history. Luplow made a leaping catch at the wall and tumbled into the bullpen while still holding the ball.

| Year | Team | League | Games | Plate Appearances | At Bats | Runs | Hits | Doubles | Triples | Home Runs | RBIs | Stolen Bases | Caught Stealing | Walks | Strikeouts | Batting Average | On-Base Percentage | Slugging Percentage | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | BRO | NL | 23 | 64 | 60 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | .200 | .250 | .333 | .583 |

| 1952 | 36 | 71 | 68 | 13 | 21 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | .309 | .329 | .397 | .726 | ||

| 1953 | 30 | 60 | 55 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 | .218 | .271 | .364 | .635 | ||

| 1954 | 16 | 37 | 34 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | .147 | .189 | .235 | .424 | ||

| 1956 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .286 | .286 | .286 | .571 | ||

| 1956 | BAL | AL | 87 | 390 | 353 | 45 | 101 | 18 | 4 | 11 | 37 | 5 | 5 | 30 | 40 | .286 | .342 | .453 | .795 |

| 1957 | 47 | 184 | 167 | 16 | 39 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 21 | .234 | .293 | .335 | .628 | ||

| 1958 | 128 | 462 | 409 | 36 | 113 | 17 | 0 | 4 | 32 | 0 | 6 | 37 | 47 | .276 | .336 | .347 | .683 | ||

| 1957 | CLE | 67 | 220 | 205 | 33 | 58 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 19 | .283 | .324 | .405 | .729 | |

| 1959 | KCA | 130 | 538 | 488 | 72 | 130 | 33 | 1 | 16 | 75 | 4 | 1 | 28 | 60 | .266 | .309 | .436 | .746 | |

| 1960 | 127 | 466 | 420 | 47 | 121 | 31 | 0 | 12 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 68 | .288 | .346 | .448 | .794 | ||

| 1961 | BAL | 103 | 340 | 310 | 37 | 64 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 24 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 38 | .206 | .251 | .345 | .596 | |

| 1962 | 82 | 197 | 178 | 20 | 44 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 26 | .247 | .303 | .315 | .617 | ||

| 1963 | BOS | 79 | 152 | 136 | 15 | 35 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 25 | .257 | .329 | .360 | .689 | |

| 1964 | 61 | 77 | 69 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 | .159 | .247 | .406 | .653 | ||

| Career (13 seasons) | 1023 | 3265 | 2959 | 358 | 768 | 157 | 12 | 70 | 331 | 12 | 21 | 227 | 392 | .260 | .312 | .392 | .704 | ||

4. Managerial Career

Dick Williams' managerial career was characterized by a hard-driving, disciplinarian approach that often yielded significant success, transforming underperforming teams into contenders. He was known for his sharp tongue and his ability to instill a winning mentality, leading teams to multiple pennants and two World Series titles.

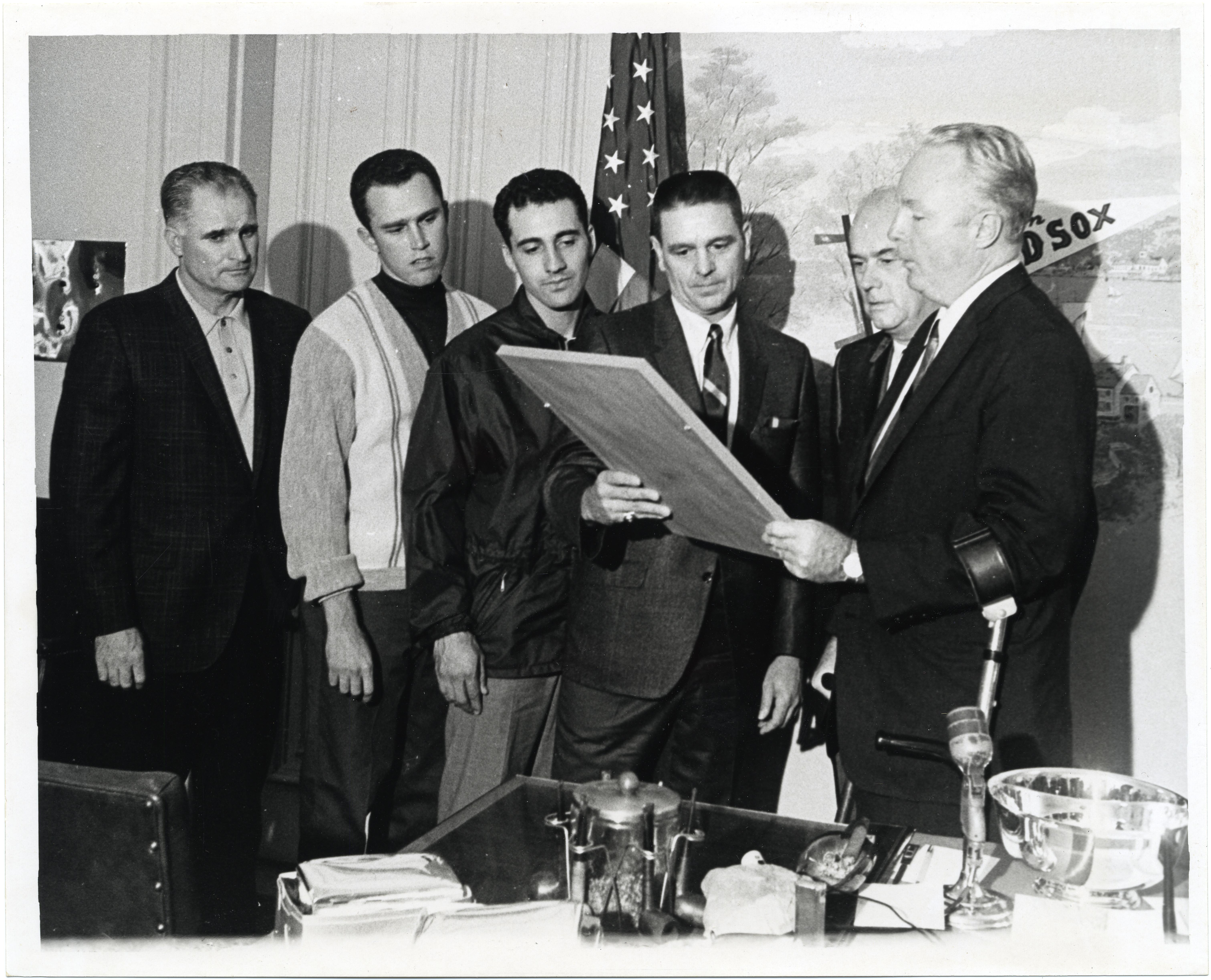

4.1. Boston Red Sox

After his playing career ended in 1964 with a career-low .159 batting average, the Red Sox released Williams. At 35, he accepted a playing coach position with the Red Sox's Triple-A affiliate, the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League. A subsequent affiliation shuffle led to the team moving to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League, and when the previous manager resigned, Williams was promoted to manager of the Maple Leafs in 1965. As a novice manager, Williams quickly established a hard-nosed, disciplinarian style, leading the Maple Leafs to two consecutive Governors' Cup championships with teams full of young Red Sox prospects. His success in the minors earned him a one-year contract to manage the 1967 Red Sox.

Boston had endured eight consecutive losing seasons, and attendance had plummeted, prompting owner Tom Yawkey to consider moving the team. Despite having talented young players, the Red Sox were known as a complacent "country club." Williams decided to take a bold risk by imposing strict discipline. He famously vowed that the team would "win more ballgames than we lose," a daring statement for a club that had finished only half a game from last place in 1966. In spring training, Williams drilled players intensely on fundamentals, issued fines for curfew violations, and insisted that team success take precedence over individual aspirations.

The Red Sox began the 1967 season playing with a newfound aggressive style, reminiscent of Williams's playing days with the Dodgers. He benched players for lack of effort and poor performance and frequently clashed with umpires. By the All-Star break, Boston had fulfilled Williams's promise, playing above .500 and staying close to the American League's top contending teams. Outfielder Carl Yastrzemski, in his seventh season, transformed his hitting style to become a pull-hitter, eventually winning the 1967 AL Triple Crown by leading the league in batting average, home runs (tied with Harmon Killebrew), and RBI.

In late July, the Red Sox embarked on a 10-game winning streak on the road, returning home to a tumultuous welcome from 10,000 fans at Logan Airport. The team inserted itself into a tight five-team pennant race and remained in contention despite the loss of star outfielder Tony Conigliaro due to a beanball on August 18. On the final weekend of the season, led by Yastrzemski and 22-game-winning pitcher Jim Lonborg, Boston defeated the Minnesota Twins in two head-to-head games, while the Detroit Tigers split their series with the California Angels. This remarkable turnaround, dubbed the ""Impossible Dream"," saw the Red Sox win their first AL pennant since 1946. They then pushed the heavily favored and highly talented St. Louis Cardinals, led by the great Bob Gibson, to seven games in the 1967 World Series, ultimately losing.

Despite the World Series loss, the Red Sox became heroes in New England. Williams was named Major League Manager of the Year by The Sporting News and signed a new three-year contract. However, his tenure would be short-lived. In 1968, the team dropped to fourth place as Conigliaro was unable to return from his head injury, and both Lonborg and José Santiago, Williams's top pitchers, suffered arm ailments. Williams began to clash with Yastrzemski and owner Yawkey. With the club a distant third in the AL East, Williams was fired on September 23, 1969, and replaced by Eddie Popowski for the final nine games of the season.

4.2. Oakland Athletics

After spending 1970 as the third base coach for the Montreal Expos under Gene Mauch, Williams returned to managing in 1971, taking the helm of the Oakland Athletics, owned by the eccentric Charlie Finley. Finley had assembled an impressive roster of talent, including Catfish Hunter, Reggie Jackson, Sal Bando, Bert Campaneris, Rollie Fingers, and Joe Rudi, which Finley famously dubbed the "Swingin' A's". However, Finley's players often resented him for his tightfistedness and constant interference in team affairs. During his first decade as the Athletics' owner (1961-1970), Finley had changed managers ten times.

Inheriting a second-place team from his predecessor, John McNamara, Williams promptly led the A's to 101 victories and their first AL West title in 1971, propelled by the brilliant young pitcher Vida Blue. Despite being defeated by the defending World Champion Baltimore Orioles in the ALCS, Finley retained Williams for the 1972 season, which marked the beginning of the "Oakland Dynasty." Off the field, the A's players were known for their internal brawls and their defiance of baseball's traditional grooming standards. Capitalizing on the popularity of long hair, mustaches, and beards in popular culture, Finley initiated a mid-season promotion encouraging his players to grow their hair long and sport facial hair. Fingers notably adopted his distinctive handlebar mustache, and Williams himself grew a mustache.

The success of the early 1970s Oakland Dynasty was ultimately attributed to talent rather than appearance. The 1972 A's secured their division by 5.5 games over the Chicago White Sox and led the league in home runs, shutouts, and saves. They went on to defeat the Detroit Tigers in a fiercely contested ALCS. In the 1972 World Series, they faced the formidable Cincinnati Reds' "Big Red Machine." With the A's leading power hitter, Jackson, sidelined due to injury, the Reds were favored to win. However, the home run heroics of Oakland catcher Gene Tenace and Williams's astute managerial strategies culminated in a seven-game World Series victory for the A's, marking their first championship since 1930, when the franchise was based in Philadelphia.

In 1973, Williams returned for an unprecedented (for the Finley era) third consecutive season. The A's once again cruised to a division title, then defeated the Baltimore Orioles in the ALCS and the NL champion New York Mets in the World Series, with both hard-fought series going the full seven games. With their second consecutive World Series win, Oakland became baseball's first repeat champion since the 1961-62 New York Yankees. However, Williams had a surprise for Finley. Exhausted by his owner's constant interference and deeply upset by Finley's public humiliation of second baseman Mike Andrews for his fielding errors during the World Series, Williams resigned. George Steinbrenner, then completing his first season as owner of the New York Yankees, immediately signed Williams as his new manager. Finley, however, protested, asserting that Williams was still under contract with Oakland for another year and could not manage elsewhere. Consequently, Steinbrenner hired Bill Virdon instead. Williams was the first manager in the A's franchise history to leave the team with a winning record after managing for two full seasons.

4.3. California Angels

Despite being at what seemed to be the peak of his career, Williams found himself unemployed at the start of the 1974 season. However, when the Angels struggled under manager Bobby Winkles, team owner Gene Autry secured Finley's permission to negotiate with Williams. Williams was back in a big-league dugout by mid-season. The change in management, however, did not improve the Angels' fortunes, as they finished in last place, 22 games behind the A's, who went on to win their third consecutive World Championship under Williams's replacement, Alvin Dark.

Overall, Williams's tenure in Anaheim proved to be a difficult one. He did not have the same level of talent he had enjoyed in Boston and Oakland, and the Angels' players did not respond well to his somewhat authoritarian managing style. They finished last in the AL West again in 1975. During that season, Boston Red Sox pitcher Bill Lee famously remarked that the Angels' hitters were "so weak, they could hold batting practice in the Boston Sheraton hotel lobby and not hit the chandelier." Williams responded by having his team actually conduct a batting practice in the hotel lobby (using Wiffle balls and bats) before a game against the Red Sox, until hotel security intervened to stop it. The Angels were 18 games below .500 and in the midst of a player revolt in 1976 when Williams was fired on July 22.

4.4. Montreal Expos

In 1977, Williams returned to Montreal as manager of the Montreal Expos, a team that had just endured 107 losses and a last-place finish in the National League East. Team president John McHale, impressed by Williams's past successes in Boston and Oakland, believed he was the leader the Expos needed to finally become a winning franchise.

After two seasons of cajoling the Expos into improved, though still below .500, performances, Williams transformed the 1979-80 Expos into legitimate pennant contenders. The team achieved over 90 wins in both years-marking the first winning seasons in franchise history. The 1979 squad recorded 95 victories, the most the franchise would ever achieve in Montreal. However, they finished second in their division each time to the eventual World Champions (the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1979 and the Philadelphia Phillies in 1980). Williams was known for his willingness to give young players opportunities, and his Expos teams were rich with emerging talent, including future All-Stars such as outfielder Andre Dawson and catcher Gary Carter. With a strong core of young players and a productive farm system, the Expos appeared poised for a sustained period of contention.

However, Williams's demanding and often abrasive demeanor began to alienate his players, particularly his pitchers, and ultimately wore out his welcome. He controversially labeled pitcher Steve Rogers a "fraud" with "king of the mountain syndrome," implying that Rogers, having been a good pitcher on a bad team for so long, was unable to elevate his performance when the team improved. Williams also lost confidence in closer Jeff Reardon, whom the Montreal front office had acquired in a highly publicized trade with the Mets for Ellis Valentine. When the 1981 Expos performed below expectations, Williams was fired during the pennant race on September 7. With the arrival of his more easy-going successor, Jim Fanning, who reinstated Reardon to the closer's role, the inspired Expos made the playoffs for the only time in their 36-year history in Montreal. However, they suffered a heartbreaking loss to Rick Monday and the eventual World Champion Los Angeles Dodgers in a five-game NLCS.

4.5. San Diego Padres

Williams's unemployment was brief. In 1982, he took over as manager of the San Diego Padres. By 1984, he had successfully guided the Padres to their first NL West Division championship. In the NLCS, the NL East champion Chicago Cubs, making their first postseason appearance since 1945, won Games 1 and 2. However, Williams's Padres staged a miraculous comeback, winning the next three games to clinch the pennant. In the 1984 World Series, San Diego proved to be no match for Sparky Anderson's Detroit Tigers, a dominant team that had won 104 games during the regular season. Although the Tigers won the Series in five games, both Williams and Anderson achieved the distinction of winning pennants in both major leagues, joining a select group of managers that included Alvin Dark, Joe McCarthy, and Yogi Berra. Other managers who later joined this exclusive group include Tony La Russa (2004), Jim Leyland (2006), Joe Maddon (2016), Dusty Baker (2021), and Bruce Bochy (2023), who was a backup catcher on that Padres team.

The Padres fell to third place in 1985, and Williams was dismissed as manager just before the 1986 spring training. His record with the Padres was 337 wins and 311 losses over four seasons. As of 2011, he held the distinction of being the only manager in the team's history to not have a losing season. His difficulties with the Padres stemmed from a power struggle with team president Ballard Smith and general manager Jack McKeon. Williams had been hired by team owner Ray Kroc, the McDonald's restaurant magnate, whose health was declining. McKeon and Smith, who was also Kroc's son-in-law, were positioning themselves to buy the team and viewed Williams as a threat to their plans. With his tenure in San Diego concluded, it appeared that Williams's managerial career might be over.

4.6. Seattle Mariners

However, Williams returned to the American League West on May 9, 1986, to manage another perennial loser, the Seattle Mariners, who had started the season with a 19-28 record under Chuck Cottier. The Mariners showed some improvement that season and nearly reached .500 the following season. Despite this, Williams's autocratic managing style, which had been successful in previous eras, no longer resonated with the new generation of ballplayers. He faced resistance from the Mariners' front office when he attempted to play the injury-plagued Gorman Thomas in the outfield, due to Thomas's medical history, specifically his rotator cuff. Additionally, Williams had difficulty connecting with devoutly religious Mariners players, such as Alvin Davis. Williams was ultimately fired on June 8, 1988, with Seattle holding a 23-33 record and in sixth place. This marked his final major-league managing job. Williams concluded his career with a total of 1,571 wins and 1,451 losses over 21 seasons.

| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| BOS | 1967 | 162 | 92 | 70 | .568 | 1st in AL | 3 | 4 | .429 | Lost World Series (STL) |

| BOS | 1968 | 162 | 86 | 76 | .531 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BOS | 1969 | 153 | 82 | 71 | .536 | fired | - | - | - | - |

| BOS total | 477 | 260 | 217 | .545 | 3 | 4 | .429 | |||

| OAK | 1971 | 161 | 101 | 60 | .627 | 1st in AL West | 0 | 3 | .000 | Lost ALCS (BAL) |

| OAK | 1972 | 155 | 93 | 62 | .600 | 1st in AL West | 7 | 5 | .583 | Won World Series (CIN) |

| OAK | 1973 | 162 | 94 | 68 | .580 | 1st in AL West | 7 | 5 | .583 | Won World Series (NYM) |

| OAK total | 478 | 288 | 190 | .603 | 14 | 13 | .519 | |||

| CAL | 1974 | 84 | 36 | 48 | .429 | 6th in AL West | - | - | - | - |

| CAL | 1975 | 161 | 72 | 89 | .447 | 6th in AL West | - | - | - | - |

| CAL | 1976 | 96 | 39 | 57 | .406 | fired | - | - | - | - |

| CAL total | 341 | 147 | 194 | .431 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| MON | 1977 | 162 | 75 | 87 | .463 | 5th in NL East | - | - | - | - |

| MON | 1978 | 162 | 76 | 86 | .469 | 4th in NL East | - | - | - | - |

| MON | 1979 | 160 | 95 | 65 | .594 | 2nd in NL East | - | - | - | - |

| MON | 1980 | 162 | 92 | 70 | .568 | 2nd in NL East | - | - | - | - |

| MON | 1981 | 55 | 30 | 25 | .545 | 3rd in NL East | - | - | - | - |

| 26 | 14 | 12 | .538 | fired | ||||||

| MON total | 727 | 380 | 347 | .523 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| SD | 1982 | 162 | 81 | 81 | .500 | 4th in NL West | - | - | - | - |

| SD | 1983 | 162 | 81 | 81 | .500 | 4th in NL West | - | - | - | - |

| SD | 1984 | 162 | 92 | 70 | .568 | 1st in NL West | 4 | 6 | .400 | Lost World Series (DET) |

| SD | 1985 | 162 | 83 | 79 | .512 | 3rd in NL West | - | - | - | - |

| SD total | 648 | 337 | 311 | .520 | 4 | 6 | .400 | |||

| SEA | 1986 | 133 | 58 | 75 | .436 | 7th in AL West | - | - | - | - |

| SEA | 1987 | 162 | 78 | 84 | .481 | 4th in AL West | - | - | - | - |

| SEA | 1988 | 56 | 23 | 33 | .411 | fired | - | - | - | - |

| SEA total | 351 | 159 | 192 | .453 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| Total | 3022 | 1571 | 1451 | .520 | 21 | 23 | .477 | |||

5. Post-retirement Activities and Hall of Fame Induction

After his managerial career concluded, Dick Williams remained involved in baseball. In 1989, he was named manager of the West Palm Beach Tropics in the Senior Professional Baseball Association, a league primarily featuring former major league players aged 35 and older. The Tropics achieved a strong regular season record of 52-20, winning the Southern Division title, but ultimately lost the league's championship game 12-4 to the St. Petersburg Pelicans. The Tropics folded at the end of the season, and the entire league ceased operations a year later.

Williams continued his involvement in the game as a special consultant to George Steinbrenner and the New York Yankees. In 1990, he published his autobiography, No More Mister Nice Guy. His acrimonious departure from the Red Sox in 1969 created a distance between him and the team throughout the remainder of the Yawkey ownership period (until 2001). However, following a change in ownership and management, he was inducted into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2006.

Williams's number was also retired by the Fort Worth Cats, a popular minor league team in Fort Worth, Texas. He had played for the Cats from 1948 to 1950 while progressing through the Dodgers' farm system. In his Hall of Fame induction speech, Williams specifically cited Bobby Bragan, his manager at Fort Worth, as a significant influence on his own career. The "New" Cats, an independent league team that revived the franchise in 2001 after the original Texas League Cats disbanded in 1964, honored Williams by retiring his number.

Williams was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in December 2007 and was formally inducted on July 27, 2008. He was also inducted into the San Diego Padres Hall of Fame in 2009 and posthumously into the Oakland Athletics Hall of Fame in 2024.

6. Personal Life

Beyond his baseball career, Dick Williams had a brief foray into acting. He appeared as an extra in the 1950 movie The Jackie Robinson Story. Before becoming a major league manager in 1967, he also appeared on television quiz shows such as Match Game and the original Hollywood Squares, where he reportedly won 50.00 K USD as a contestant.

Williams was married to Norma Mussato, and together they had three children: Marc, Rick, and Kathi. His son, Rick Williams, followed in his father's footsteps to some extent, playing as a minor league pitcher and later serving as a major league pitching coach before becoming a professional scout for the Atlanta Braves.

7. Controversies and Legal Issues

In January 2000, Dick Williams faced indecent exposure charges in Florida, to which he pleaded no contest. The complaint against him alleged that he was "walking naked and masturbating" on the balcony outside his hotel room. Williams later clarified that he was not fully aware of the specific details of the complaint when he entered his plea. He stated that while he was standing naked at the balcony door, he was not actually on the balcony and denied masturbating.

This incident occurred just weeks before the Veterans Committee was scheduled to vote on Baseball Hall of Fame inductees. The arrest appeared to significantly impact the committee's consideration of Williams, and he was not inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame until 2008. Williams himself acknowledged the impact, telling The New York Times that "What happened to me down in Fort Myers when I was arrested evidently hurt me quite a bit."

8. Evaluation and Impact

Dick Williams's legacy as a manager is defined by his hard-driving, uncompromising style and his remarkable ability to transform struggling teams into champions. His approach, often described as authoritarian and sharp-tongued, instilled a rigorous discipline that many players initially resisted but ultimately credited for their success. He was a master tactician who emphasized fundamentals and demanded unwavering effort, a philosophy that revitalized the Boston Red Sox in 1967 and forged the "Swingin' A's" into back-to-back World Series winners in 1972 and 1973.

Williams's impact on player development was evident in his willingness to give young talent opportunities, as seen with the Montreal Expos in the late 1970s. He pushed players to their limits, sometimes leading to friction and player revolts, but often extracting peak performance. His career demonstrated that a strong, even confrontational, managerial presence could be a powerful catalyst for team success, particularly in an era that still valued strict hierarchies. However, his later struggles with the Seattle Mariners highlighted that his autocratic style became less effective with a new generation of players who preferred a different approach to management and communication. Despite these challenges, Williams's influence on baseball strategy and team culture remains significant, marking him as one of the most impactful and distinctive managers of his era.

9. Death

Dick Williams died on July 7, 2011, at the age of 82. He passed away at a hospital near his home in Henderson, Nevada, due to a ruptured aortic aneurysm. His wife, Norma Williams, passed away shortly after him, on August 4, 2011, at the age of 79.