1. Overview

Diane Arbus (March 14, 1923 - July 26, 1971), born Diane Nemerov, was an American photographer renowned for her unique and often unsettling portraits. She expanded the accepted notions of photographic subject matter, delving into the lives of individuals often marginalized by society, such as strippers, carnival performers, nudists, people with dwarfism, and those with physical or intellectual disabilities. Her approach was characterized by a direct, unadorned frontal style, capturing a rare psychological intensity by befriending, rather than objectifying, her subjects. Arbus was fascinated by people who visibly crafted their own identities, as well as those seemingly trapped by societal roles.

Her work transformed the art of photography, influencing generations of artists by normalizing previously overlooked groups and emphasizing the importance of diverse representation. Arbus achieved significant recognition during her lifetime, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and inclusion in the influential "New Documents" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1967. A year after her death by suicide at age 48, she became the first photographer to be featured in the Venice Biennale, and a major MoMA retrospective of her work attracted record attendance. Her iconic work, accompanied by her belief that "a photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know," continues to provoke discussion and solidify her place as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

2. Early Life and Background

Diane Arbus's formative years were shaped by a privileged upbringing within a wealthy New York family, which paradoxically led to feelings of isolation and a unique perspective on human experience.

2.1. Childhood and Family

Diane Nemerov was born on March 14, 1923, in New York City, the second child and eldest daughter of David Nemerov and Gertrude Russek Nemerov. Her parents were Jewish immigrants from Soviet Russia and Poland. Her maternal grandfather, Frank Russek, a Polish-Jewish immigrant, co-founded Russeks, a prominent women's wear department store on Fifth Avenue, where her father, David, eventually became chairman. The family's considerable wealth insulated Arbus from the hardships of the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Despite their affluence, Arbus and her siblings were primarily raised by maids and governesses, as her mother was preoccupied with a busy social life and experienced a period of clinical depression, while her father was deeply immersed in his work. Arbus felt a sense of detachment from her lavish childhood, perceiving herself as a "shabby princess," simultaneously protected and monitored, leading to a feeling of loneliness. She was particularly close to her older brother, Howard Nemerov, who became a distinguished poet and United States Poet Laureate. Her younger sister, Renee, became a sculptor and designer. Diane and Howard, both intellectually bright, built their own world through books, maintaining a distinct independence that sometimes drew criticism from adults. Her early personality was marked by isolation, creativity, and a sensitive, perceptive nature. As a teenager, Arbus became acutely aware of her distinctiveness, often captivating others but then quietly withdrawing to her own solitude. She showed an early interest in observing her own body and contemplating female sexuality.

2.2. Education

Arbus began her formal education in 1930 at the Ethical Culture School on Central Park West, a school that emphasized action and a passion for learning. She was described as a quiet, exceptionally intelligent student, showing particular talent in vocabulary, reading, and drawing. Her assignments often reflected her unique inner world.

From seventh to twelfth grade, she attended the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, a college-preparatory institution. Here, she was captivated by educational themes exploring the duality of human civilization and primitiveness, as well as the origins and development of mythology. Her enthusiasm for art flourished, and she produced various drawings, croquis, pencil sketches, caricatures, and murals. Her art teacher and mentor, Victor D'Amico, even suggested she pursue a career as a painter, recognizing her significant talent, which Arbus later recalled as both a "burden and a blessing."

Later in her life, at the age of 35 in 1958, Arbus enrolled in The New School. Her formal photographic training began shortly after her marriage, when she took classes with photographer Berenice Abbott. In 1941, her interest in photography led her and Allan to visit the gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, where they learned about the works of photographers such as Mathew Brady, Timothy O'Sullivan, Paul Strand, Bill Brandt, and Eugène Atget. However, it was her studies with Lisette Model, which commenced in 1956, that profoundly influenced her, encouraging her to dedicate herself entirely to her personal photographic vision.

3. Personal Life

Diane Arbus's personal life was deeply intertwined with her artistic journey, marked by significant relationships and a continuous search for connection and understanding.

3.1. Marriage, Children, and Relationships

In 1941, at the age of 18, Diane Nemerov married her childhood sweetheart, Allan Arbus, whom she had been dating since she was 14. Their relationship was intensely deep and unconventional, defying her family's strong opposition. She even used a fake boyfriend, Arthur Weinstein, to conceal their secret romance.

The couple had two daughters: Doon, born in 1945, who later became a writer, and Amy, born in 1954, who followed in her mother's footsteps as a photographer. Diane was described as a very affectionate and close mother to Doon, actively supporting her exploration of diverse experiences. Allan, who originally aspired to a career in theater, put his dreams aside to support his family, deciding to work with Diane in fashion photography.

Diane and Allan separated in 1959, though they maintained a close friendship and continued to share a darkroom. Allan's studio assistants would process her negatives, and she would print her work there. Their divorce was finalized in 1969 when Allan moved to California to pursue his acting career, where he gained popularity for his role as Dr. Sidney Freedman on the television show M*A*S*H. Despite the distance, they maintained a long correspondence.

In late 1959, Arbus began a significant relationship with Marvin Israel, an art director and painter, which lasted until her death. Israel, who remained married to Margaret Ponce Israel, was a crucial creative influence and champion of Arbus's work, encouraging her to create her first portfolio. Among her circle of friends and artists was photographer Richard Avedon, who was close in age and shared a similar background, as his family also ran a Fifth Avenue department store. Many of Avedon's photographs, like Arbus's, were characterized by detailed frontal poses.

4. Photographic Career

Diane Arbus's photographic career evolved from commercial fashion work to a groundbreaking exploration of fine art photography, marked by a distinctive style and a profound engagement with her subjects.

4.1. Early Career and Commercial Photography

Diane Arbus received her first camera, a Graflex, from Allan shortly after their marriage. Their mutual interest in photography led them to visit Alfred Stieglitz's gallery in 1941, where they were introduced to the works of prominent photographers. In the early 1940s, Diane's father hired both Diane and Allan to create advertisements for the Russeks department store. Allan also served as a photographer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War II.

In 1946, following the war, the Arbuses established a commercial photography business named "Diane & Allan Arbus." Diane served as the art director, developing concepts for their shoots and managing models, while Allan handled the photography. Despite their success, Diane grew increasingly dissatisfied with her role, finding it "demeaning." They contributed to major magazines such as Glamour, Seventeen, Vogue, and Harper's Bazaar, even though both expressed a strong dislike for the fashion world. Although they produced over 200 pages of fashion editorial for Glamour and more than 80 pages for Vogue, their fashion photography was often described as being of "middling quality." Notably, Edward Steichen's renowned 1955 exhibition, The Family of Man, included a photograph by the Arbuses depicting a father and son reading a newspaper.

4.2. Transition to Fine Art Photography and Stylistic Development

Arbus briefly studied with Alexey Brodovich in 1954, but it was her studies with Lisette Model, beginning in 1956, that truly inspired her to concentrate solely on her own artistic endeavors. In that pivotal year, Arbus left the commercial photography business and began systematically numbering her negatives, a practice she continued until her last known negative, #7459. Model's advice encouraged Arbus to spend time with an empty camera, practicing observation. Arbus often credited Model with the profound insight that "the more specific you are, the more general it'll be."

By 1956, Arbus was working with a 35mm Nikon camera, wandering the streets of New York City and encountering most of her subjects by chance. Her early post-studio work was characterized by grainy, rectangular images. However, around 1962, she transitioned to a twin-lens reflex Rolleiflex camera, which produced more detailed square images. She explained this shift by saying, "In the beginning of photographing I used to make very grainy things... But when I'd been working for a while with all these dots, I suddenly wanted terribly to get through there. I wanted to see the real differences between things... I began to get terribly hyped on clarity." In 1964, she further evolved her technique by incorporating a 2-1/4 Mamiyaflex camera with flash, in addition to her Rolleiflex. This innovative use of flash in daylight became a hallmark of her style, isolating subjects from their backgrounds and contributing to the surreal quality of her photographs.

4.3. Key Subjects and Themes

Arbus's work largely revolved around the concept of personal identity as socially constructed. She was fascinated by individuals who visibly created their own identities, such as cross-dressers, nudists, sideshow performers, tattooed men, the nouveaux riches, and movie-star fans. She also explored those who seemed trapped in a "uniform" that offered no security or comfort. Her subjects included a wide range of marginalized individuals, often referred to as "freaks" in her time, such as people with dwarfism, giants, transsexuals, and carnival performers, as well as children, mothers, couples, elderly people, and middle-class families.

Critics have suggested that her choice of subjects reflected her own identity issues, stemming from a childhood where she never experienced adversity and consequently longed for experiences that money could not buy, particularly within the "underground social world." Arbus is widely praised for the empathy she showed her subjects, a quality often conveyed through her writings and the testimonies of those she photographed. She believed that while a camera could be cold and harsh, its precision could reveal the truth, especially the "flaws" - the discrepancies between how people wished to be seen and how they actually appeared.

From 1969 until her death, Arbus dedicated herself to a series of photographs of developmentally and intellectually disabled people residing in New Jersey facilities, a body of work posthumously titled Untitled. She revisited these facilities repeatedly for events like Halloween parties, picnics, and dances, describing these photographs as "lyric and tender and pretty." She was captivated by her subjects' "absolute immersion" in their activities, regardless of being photographed. Arbus's work consistently challenged societal taboos, drawing both acclaim and criticism. Her approach marked a departure from traditional documentary photography, fostering a new dynamic where both the photographer and the subject revealed themselves to the camera and to each other. She was able to look directly at faces from which others might avert their eyes, finding both beauty and pain within them. Her work, though often challenging, was never cruel; she confronted the "terror of darkness" and remained articulate in her vision.

4.4. Photographic Techniques and Equipment

Arbus's distinctive photographic style is characterized by its directness and unadorned quality, typically featuring a frontal portrait centered within a square format. Her pioneering use of flash in daylight was a key technical innovation, serving to isolate her subjects from their backgrounds and imparting a surreal, almost theatrical quality to her images.

Beyond technical aspects, Arbus's methodology involved establishing strong personal relationships with her subjects. She often spent considerable time with them, sometimes re-photographing the same individuals over many years, allowing for a deeper connection and a more intimate portrayal. Her primary cameras evolved over her career: she started with a Graflex, then used a 35mm Nikon, which produced grainy rectangular images. Around 1962, she switched to a twin-lens reflex Rolleiflex, known for its ability to capture more detailed square images. By 1964, she further incorporated a 2-1/4 Mamiyaflex camera, often used in conjunction with her signature flash.

4.5. Major Exhibitions and Awards

Despite achieving widespread publication and artistic recognition, Diane Arbus faced financial struggles throughout her career. During her lifetime, there was no established market for collecting photographs as works of art, and her prints typically sold for 100 USD or less. Her correspondence reveals that a lack of money was a persistent concern.

In 1963, Arbus was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship for her project titled "American Rites, Manners and Customs," a fellowship that was renewed in 1966. Throughout the 1960s, she largely supported herself through magazine assignments and commissions. For instance, in 1968, she photographed impoverished sharecroppers in rural South Carolina for Esquire magazine, and in 1969, she was commissioned by actor and theater owner Konrad Matthaei and his wife, Gay, to photograph a family Christmas gathering. Her notable portrait subjects included Mae West, Ozzie Nelson and Harriet Nelson, Bennett Cerf, atheist Madalyn Murray O'Hair, Norman Mailer, Jayne Mansfield, Eugene McCarthy, billionaire H. L. Hunt, Gloria Vanderbilt's infant son Anderson Cooper, Coretta Scott King, and Marguerite Oswald (Lee Harvey Oswald's mother). As her fame as an artist grew, her magazine assignments generally decreased. In 1970, John Szarkowski, the director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), hired Arbus to research an exhibition on photojournalism called "From the Picture Press," which featured many photographs by Weegee, whose work Arbus admired. She also shared her expertise by teaching photography at the Parsons School of Design and the Cooper Union in New York City, and at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island.

Late in her career, the Metropolitan Museum of Art expressed interest in purchasing three of her photographs for 75 USD each but ultimately bought only two, citing a lack of funds. Arbus wrote to Allan Arbus, "So I guess being poor is no disgrace."

In May 1971, Artforum published six photographs from Arbus's portfolio, A box of ten photographs, including a cover image. Philip Leider, then editor-in-chief of Artforum and a photography skeptic, admitted after encountering Arbus's portfolio that "With Diane Arbus, one could find oneself interested in photography or not, but one could no longer . . . deny its status as art." She was the first photographer to be featured in Artforum, and Leider's acceptance of her work into this critical bastion of late modernism was instrumental in elevating photography's status as "serious" art.

The first major exhibition of her photographs took place at the Museum of Modern Art in the influential "New Documents" show in 1967, curated by John Szarkowski. Her work was exhibited alongside that of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. "New Documents" attracted nearly 250,000 visitors and aimed to present "a new generation of documentary photographers...whose aim has been not to reform life but to know it," focusing on "the pathos and conflicts of modern life presented without editorializing or sentimentalizing." The exhibition was polarizing, drawing both praise and criticism, with some viewers perceiving Arbus as a disinterested voyeur and others commending her evident empathy for her subjects.

In 2018, The New York Times published a belated obituary for Arbus as part of its "Overlooked" history project. The Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) hosted an exclusive exhibition of Arbus's portfolio, A box of ten photographs, from April 6, 2018, to January 27, 2019. This collection is one of only four complete editions that Arbus personally printed and annotated, with the other three held privately. The SAAM edition was originally made for Bea Feitler, an art director who both employed and befriended Arbus. After Feitler's death, the portfolio was purchased at Sotheby's in 1982 for 42.90 K USD by Baltimore collector G. H. Dalsheimer, and then acquired by SAAM in 1986.

In 1972, a year after her suicide, Arbus made history as the first photographer to be included in the Venice Biennale, where her photographs were hailed as "the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion" and described as "extremely powerful and very strange." The first major retrospective of Arbus's work was held later that year at MoMA, organized by Szarkowski. This retrospective garnered the highest attendance of any exhibition in MoMA's history at that time, and millions viewed traveling exhibitions of her work from 1972 to 1979. The book accompanying the exhibition, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, edited by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel and first published in 1972, has remained continuously in print.

5. Artistic Philosophy and Vision

Diane Arbus's artistic philosophy was deeply rooted in her fascination with the human condition and her unique approach to capturing reality. She famously stated, "A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know." She believed that while the camera might appear cold and harsh, its meticulous detail could unveil profound truths, particularly the "flaws" that exist between how individuals wish to be perceived and how they are actually seen.

Arbus was captivated by the idea of personal identity as a social construct. Her work explored the lives of those who visibly crafted their own identities, such as performers and individuals using makeup or masks, as well as those who seemed confined by societal expectations. Critics have suggested that her choice of subjects was influenced by her own experiences, having grown up in privilege without experiencing adversity, which fostered a longing for the "underground social world" and experiences that money could not buy.

She was widely praised for her empathetic approach to her subjects, a quality often evident in her writings and the testimonies of the people she photographed. Arbus aimed to photograph "everyone," believing that the most personal and private aspects of individuals could be universally understood and accepted. She was particularly drawn to the "absolute immersion" she observed in her subjects, especially those with developmental disabilities, who seemed entirely absorbed in their own actions, indifferent to the camera.

Arbus's work challenged traditional documentary photography, creating a new dynamic where both the photographer and the subject actively revealed themselves. She was committed to confronting the "terror of darkness" and maintaining articulation in her art, even when depicting difficult subjects. Ultimately, Arbus sought to find "unvarnished, perfect humanity" within imperfection, believing that humanity itself, in all its forms, was beautiful.

6. Critical Reception and Impact

Diane Arbus's work has consistently evoked strong and varied responses from critics, artists, and the public, establishing her as a pivotal figure in photography and art history.

6.1. Positive Reception

Arbus received significant acclaim for her groundbreaking vision and her ability to capture intense psychological depth. Many critics praised her empathy towards her subjects and her role in elevating photography to a recognized art form.

In a 1967 review of MoMA's "New Documents" exhibition, Max Kozloff noted that Arbus's "refusal to be compassionate, her revulsion against moral judgment, lends her work an extraordinary ethical conviction." Writing for Arts Magazine, Marion Magid observed that while the exhibit had the "criminal allure of a sideshow," Arbus's art ultimately "sanctify[ied] that privacy which she seems at first to have violated," healing the viewer's "criminal urgency" to stare.

Robert Hughes, in a 1972 Time magazine review of the MoMA retrospective, declared that Arbus "altered our experience of the face." Hilton Kramer, reviewing the same exhibition, stated that Arbus was "one of those figures...who suddenly, by a daring leap into a territory formerly regarded as forbidden, altered the terms of the art she practiced." He added that she "completely wins us over, not only to her pictures but to her people, because she has clearly come to feel something like love for them herself."

Later critics continued to laud her unique vision. David Pagel, in a 1992 review of the Untitled series, described them as "some of the most hauntingly compassionate images made with a camera," noting their "remarkable" range of expressions and how they combine universal sentiments with unimaginable experiences. Nan Goldin, reviewing Untitled for Artforum in 1995, praised Arbus's ability to "let things be, as they are," and her "ability to empathize, on a level far beyond language." Goldin asserted that Arbus "could travel, in the mythic sense," trying on "the skins of others" and facing "the terror of darkness" while remaining articulate. Hilton Als (1995) found the Untitled series to be as "iconographic as it gets in any medium."

Francine Prose, in her 2003 review of the "Diane Arbus: Revelations" exhibition, suggested that Arbus's work could be seen as "the bible of a faith" in "the individual and irreducible human soul," a "church of obsessive fascination and compassion for those fellow mortals whom...we thoughtlessly misidentify as the wretched of the earth." Barbara O'Brien (2004) found her work "filled with life and energy."

Peter Schjeldahl (2005) famously stated that Arbus "turned picture-making inside out," inducing subjects to gaze at her with an intense presence that "disintegrates" any preconceived attitudes. He concluded that "No other photographer has been more controversial. Her greatness, a fact of experience, remains imperfectly understood." Michael Kimmelman (2005) highlighted the "grace" with which Arbus touched her favorite subjects, finding "beauty in flaws." Ken Johnson (2005) called her "the Flannery O'Connor of photography," noting how her images aroused "an almost painfully urgent curiosity." Leo Rubinfien (2005) emphasized that "No photographer makes viewers feel more strongly that they are being directly addressed," and that Arbus loved "conundrum, contradiction, riddle," connecting her work to Kafka and Beckett in its delicate balance between laughter and tears.

More recently, Mark Feeney (2016) observed that Arbus "changed how we allow ourselves to see" the world, witnessing "without ever judging." Arthur Lubow (2018), reviewing the Untitled series, compared them to paintings by Ensor, Bruegel, and Goya, asserting that "nothing can surpass the strange beauty of reality if a photographer knows where to look." Adam Lehrer (2018) concluded that Arbus "found unvarnished, perfect humanity" within imperfection, and that "humanity, to Arbus, was beautiful."

6.2. Criticism and Controversy

Despite widespread acclaim, Arbus's work also faced significant criticism, particularly concerning the ethics of her subject matter and the portrayal of vulnerable individuals.

Susan Sontag's influential 1973 essay "Freak Show" (reprinted in her 1977 book On Photography as "America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly") was highly critical. Sontag argued against the perceived lack of beauty in Arbus's work and its failure to evoke compassion for her subjects, famously stating that Arbus's subjects were "all members of the same family, inhabitants of a single village. Only, as it happens, the idiot village is America." Sontag's essay itself was criticized as an "exercise in aesthetic insensibility" and "exemplary for its shallowness." It was also noted that Arbus had photographed Sontag and her son in 1965, leading some to question if Sontag's critique was influenced by her own portrait. Despite its faults, Sontag's critique continues to inform much of the scholarship on Arbus's oeuvre. Sontag also commented on the "contrast between their lacerating subject matter and their calm, matteroffact attentiveness," which created "the moral theater" of Arbus's portraits, questioning if her subjects knew "how grotesque they are."

Judith Goldman (1974) posited that "Arbus' camera reflected her own desperateness in the same way that the observer looks at the picture and then back at himself." Stephanie Zacharek (2006), reviewing the film Fur, expressed that she saw in Arbus's pictures "a desire to confirm her suspicions about humanity's dullness, stupidity, and ugliness." Wayne Koestenbaum (2007) questioned whether Arbus's photographs humiliated the subjects or the viewers, though he later acknowledged that she found "little pockets of jubilation" and "beauty, staunchness, pattern" within the apparent "abjection."

Some of Arbus's subjects and their relatives also offered critical perspectives on their experience. The father of the twins in "Identical Twins, Roselle, N.J. 1967" stated, "We thought it was the worst likeness of the twins we'd ever seen... she made them look ghostly." Writer Germaine Greer, photographed by Arbus in 1971, called her own portrait an "undeniably bad picture" and dismissed Arbus's work as unoriginal, focusing on "mere human imperfection and self-delusion." Norman Mailer famously remarked in 1971, "Giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like putting a live grenade in the hands of a child," reportedly displeased with his "spread-legged" portrait taken by Arbus in 1963 for The New York Times Book Review. Conversely, Colin Wood, the subject of Child With a Toy Grenade in Central Park, felt that Arbus "saw in me the frustration, the anger at my surroundings, the kid wanting to explode but can't because he's constrained by his background."

The management of Arbus's estate by her daughter, Doon Arbus, also generated controversy. As Arbus died without a will, Doon assumed responsibility for her work. She forbade examination of Arbus's correspondence and frequently denied permission for exhibition or reproduction of photographs without prior vetting, drawing the ire of many critics and scholars. A 1993 academic journal published a complaint regarding the estate's control and alleged attempts to censor characterizations of subjects and the photographer's motives. A 2005 article suggested this control was an attempt to "control criticism and debate." However, it is also common institutional practice in the U.S. to limit the number of images provided for media use in exhibition press kits. The estate was also criticized in 2008 for minimizing Arbus's early commercial work, though these photographs were primarily taken by Allan Arbus and credited to the "Diane and Allan Arbus Studio." In 2011, scholar William Todd Schultz referenced the "famously controlling Arbus estate" who, he noted, "seem to have this idea...that any attempt to interpret the art diminishes the art."

7. Publications

Diane Arbus's photographic legacy is preserved and disseminated through several key publications, many of which were compiled and edited posthumously.

- Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph. Edited by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel.

- New York: Aperture, 1972.

- New York: Aperture, 1997.

- Fortieth-anniversary edition. New York: Aperture, 2011.

- New York: Aperture, 2022.

- This monograph accompanied the 1972 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. It contained eighty of Arbus's photographs, along with texts from classes she taught in 1971, some of her writings, and interviews. Between 2001 and 2004, it was selected as one of the most important photobooks in history and has never been out of print since its initial publication.

- Diane Arbus: Magazine Work. Edited by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel. With texts by Diane Arbus and an essay by Thomas W. Southall.

- New York: Aperture, 1984.

- London: Bloomsbury, 1992.

- Untitled. Edited by Doon Arbus and Yolanda Cuomo.

- New York: Aperture, 1995.

- New York: Aperture, 2011.

- Diane Arbus: Revelations. New York: Random House, 2003.

- This publication includes essays by Sandra S. Phillips ("The question of belief") and Neil Selkirk ("In the darkroom"), a chronology by Elisabeth Sussman and Doon Arbus (incorporating text by Diane Arbus), an afterword by Doon Arbus, and biographies of fifty-five of Arbus's friends and colleagues by Jeff L. Rosenheim. It accompanied an exhibition that premiered at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Because the exhibition and book were approved by Arbus's estate, the chronology within the book is considered the first authorized biography of the photographer.

- Diane Arbus: A Chronology, 1923-1971. New York: Aperture, 2011. By Elisabeth Sussman and Doon Arbus.

- This volume contains the chronology and biographies originally featured in Diane Arbus: Revelations.

- Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus & Howard Nemerov. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2015. By Alexander Nemerov.

- diane arbus: in the beginning. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016. By Jeff L. Rosenheim.

- This book accompanied an exhibition that premiered at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs. New York: Aperture, 2018. By John P. Jacob.

- This publication accompanied an exhibition that premiered at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

8. Notable Photographs

Diane Arbus is celebrated for a body of iconic photographs that challenged conventions and captured the raw essence of her subjects. Her most well-known works include:

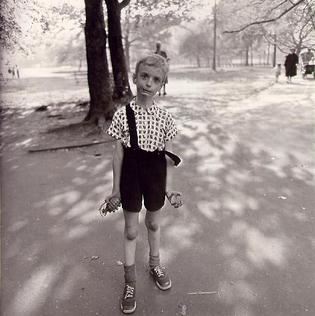

Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962 (1962)

Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962 (1962): This photograph features Colin Wood, standing tensely with his long, thin arms by his side, the left strap of his jumper awkwardly hanging off his shoulder. He clenches a toy grenade in his right hand, his left hand in a claw-like gesture, and his face expresses consternation. Analysis of the contact sheet reveals Arbus's deliberate editorial choice in selecting this specific image. A print of this photograph set an auction record for Arbus in 2015, selling for 785.00 K USD.

Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967

Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967 (1967): Features young twin sisters Cathleen and Colleen Wade standing side-by-side in dark dresses. While their uniform clothing and haircuts emphasize their twin identity, their distinct facial expressions powerfully highlight their individuality. This photograph is famously echoed in Stanley Kubrick's film The Shining, which features ghostly twins in a similar pose. A print of this work sold at auction for 732.50 K USD in 2018.

- Teenage Couple on Hudson Street, N.Y.C., 1963: This image portrays two adolescents in long coats, whose "worldlywise expressions" make them appear older than their actual age.

- Triplets in Their Bedroom, N.J. 1963: Depicts three young girls seated at the head of a bed.

- A Young Brooklyn Family Going for a Sunday Outing, N.Y.C. 1966: Features Richard and Marylin Dauria, who lived in the Bronx, with Marylin holding their baby daughter and Richard holding the hand of their young son, who is intellectually disabled.

- A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. 1966: A close-up portrait showing the man's pock-marked face with plucked eyebrows, his hand with long fingernails holding a cigarette. Early reactions to this photograph were strong; it was reportedly spat on at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967. A print sold for 198.40 K USD at a 2004 auction.

- Boy With a Straw Hat Waiting to March in a Pro-War Parade, N.Y.C. 1967: The subject stands with an American flag, wearing a bow tie, a bow tie-shaped pin with an American flag motif, and two button badges reading "Bomb Hanoi" and "God Bless America / Support Our Boys in Viet Nam." This image can evoke mixed feelings of difference and sympathy in the viewer. An art consulting firm purchased a print for 245.00 K USD at a 2016 auction.

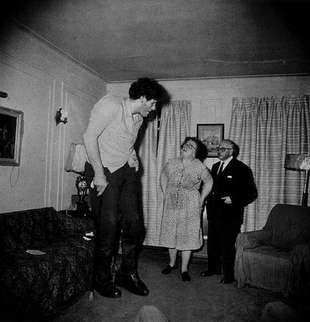

Eddie Carmel, Jewish Giant, taken at Home with His Parents in the Bronx, New York, 1970

A Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents in The Bronx, N.Y. 1970: Features Eddie Carmel, known as the "Jewish Giant," standing in his family's apartment with his much shorter mother and father. Arbus reportedly commented to a friend about this picture: "You know how every mother has nightmares when she's pregnant that her baby will be born a monster?... I think I got that in the mother's face...." This photograph later inspired Carmel's cousin to narrate a 1999 audio documentary about him. A print sold at auction for 583.50 K USD in 2017.

- A Family on Their Lawn One Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. 1968: Shows a woman and a man sunbathing, with a boy bending over a small plastic wading pool behind them. In 1972, when producing an exhibition print of this image, Neil Selkirk was advised by Marvin Israel to make the background trees appear "like a theatrical backdrop that might at any moment roll forward across the lawn," illustrating the fundamental dialectic between appearance and substance in Arbus's art. A print sold at auction for 553.00 K USD in 2008.

- A Naked Man Being a Woman, N.Y.C. 1968: The subject is depicted in a pose reminiscent of "Venus-on-the-half-shell" (referencing Botticelli's The Birth of Venus) or as a "Madonna turned in contrapposto" with his penis hidden between his legs. The parted curtain behind him enhances the theatrical quality of the photograph.

- A Very Young Baby, N.Y.C. 1968: A photograph taken for Harper's Bazaar, depicting Gloria Vanderbilt's then-infant son, the future CNN anchorman Anderson Cooper.

In addition to individual prints, Arbus's A box of ten photographs was a significant portfolio created between 1963 and 1970. It was presented in a clear Plexiglas box/frame designed by Marvin Israel, intended to be a limited edition of 50. However, Arbus completed only eight boxes and sold just four during her lifetime (two to Richard Avedon, one to Jasper Johns, and one to Bea Feitler). After Arbus's death, under the auspices of the Estate of Diane Arbus, Neil Selkirk, a former student, began printing to complete the intended edition of 50. In 2017, one of these posthumous editions sold for 792.50 K USD.

9. Death

Diane Arbus experienced severe "depressive episodes" throughout her life, similar to those suffered by her mother. These episodes may have been exacerbated by symptoms of hepatitis. In a letter to a friend, Carlotta Marshall, in 1968, Arbus described her emotional volatility: "I go up and down a lot. Maybe I've always been like that. Partly what happens though is I get filled with energy and joy and I begin lots of things or think about what I want to do and get all breathless with excitement and then quite suddenly either through tiredness or a disappointment or something more mysterious the energy vanishes, leaving me harassed, swamped, distraught, frightened by the very things I thought I was so eager for! I'm sure this is quite classic." Her ex-husband, Allan Arbus, also noted her "violent changes of mood."

As her final moments approached, Arbus became more explicit about her depression to those around her. On July 26, 1971, while residing at the Westbeth Artists Community in New York City, Diane Arbus died by suicide. She ingested barbiturates and cut her wrists with a razor. She left a diary entry with the words "Last Supper" and placed her appointment book on the stairs leading to the bathroom. Her body was discovered in the bathtub two days later by Marvin Israel. She was 48 years old. The autopsy determined the cause of death as acute barbiturate poisoning. Photographer Joel Meyerowitz later reflected on her death, telling journalist Arthur Lubow, "If she was doing the kind of work she was doing and photography wasn't enough to keep her alive, what hope did we have?"

10. Legacy

Diane Arbus's work has left an indelible mark on photography and contemporary art. As art critic Robert Hughes wrote in 1972, "[Arbus's] work has had such an influence on other photographers that it is already hard to remember how original it was." She is widely regarded as "a seminal figure in modern-day photography and an influence on three generations of photographers," and is considered among the most influential artists of the last century.

Her influence extended beyond the art world into popular culture. When Stanley Kubrick's film The Shining was released in 1980, millions of viewers unknowingly experienced Arbus's legacy. The film's iconic identical twin girls, dressed alike, were a direct result of a suggestion from crew member Leon Vitali, who recommended Arbus's infamous photograph Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967 as a point of reference for the characters, who were not originally conceived as twins in Kubrick's script.

As Arbus died without a will, the responsibility for managing her extensive body of work fell to her daughter, Doon Arbus. Doon's strict control over her mother's archives, including forbidding examination of correspondence and often denying permission for exhibition or reproduction without prior vetting, drew considerable criticism from many critics and scholars. For instance, an academic journal published a two-page complaint in 1993 regarding the estate's control and alleged attempts to censor interpretations of subjects and Arbus's motives. A 2005 article criticized the estate's allowance of only fifteen photographs for British press reproduction as an attempt to "control criticism and debate." However, it is also a common institutional practice in the U.S. to limit the number of images provided for media use in exhibition press kits. The estate was also criticized in 2008 for minimizing Arbus's early commercial work, although these photographs were primarily taken by Allan Arbus and credited to the "Diane and Allan Arbus Studio." In 2011, William Todd Schultz, author of an unauthorized biography, referenced the "famously controlling Arbus estate" who, he noted, "seem to have this idea...that any attempt to interpret the art diminishes the art."

Despite these controversies, Arbus's posthumous recognition continued to grow. In 1972, she became the first photographer to be included in the Venice Biennale, where her photographs were hailed as "the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion" and an "extraordinary achievement." The Museum of Modern Art held a major retrospective of her work, curated by John Szarkowski, in late 1972. This exhibition subsequently traveled across the United States and Canada through 1975, with an estimated seven million people viewing it. A different retrospective, curated by Marvin Israel and Doon Arbus, toured internationally between 1973 and 1979.

The 1972 book, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, edited and designed by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel, published by Aperture, accompanied the MoMA exhibition. It featured eighty of Arbus's photographs, along with texts from her 1971 classes, some of her writings, and interviews. Between 2001 and 2004, this monograph was recognized as one of the most important photobooks in history and has remained continuously in print. Neil Selkirk, a former student of Arbus's, began printing for the 1972 MoMA retrospective and the Aperture Monograph, and remains the only person authorized to make posthumous prints of her work.

A half-hour documentary film about Arbus's life and work, titled Masters of Photography: Diane Arbus or Going Where I've Never Been: The Photography of Diane Arbus, was produced in 1972 and released on video in 1989. Its voiceover was drawn from recordings of Arbus's photography classes by Ikkō Narahara and voiced by Mariclare Costello, a friend of Arbus and ex-wife of Allan Arbus.

In 1984, Patricia Bosworth published an unauthorized biography of Arbus, which reportedly received no cooperation from Arbus's daughters, her father, or close friends like Avedon and Marvin Israel. The book was criticized for insufficient consideration of Arbus's own words, speculation about missing information, and an undue focus on "sex, depression and famous people" rather than her art. In 1986, Arbus was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Between 2003 and 2006, Arbus and her work were the subject of another major traveling exhibition, Diane Arbus Revelations, organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Accompanied by a book of the same name, the exhibition included artifacts such as correspondence, books, and cameras, alongside 180 photographs. By making substantial public excerpts from Arbus's letters, diaries, and notebooks, the exhibition and book aimed to establish a definitive account of her life and death. Because Arbus's estate approved the exhibition and book, the chronology in the book is effectively considered the first authorized biography of the photographer. In 2006, the fictional film Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus was released, starring Nicole Kidman as Arbus, drawing inspiration from Patricia Bosworth's unauthorized biography. Critics generally took issue with the film's "fairytale" portrayal of Arbus.

In 2007, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired twenty of Arbus's photographs, valued at millions of dollars, and received her archives as a gift from her estate. These archives included hundreds of early and unique photographs, as well as negatives and contact prints from 7,500 rolls of film. In 2018, The New York Times published a belated obituary for Arbus as part of its "Overlooked" history project.

11. Notable Solo Exhibitions

Diane Arbus's work has been featured in numerous significant solo exhibitions, both during her lifetime and posthumously, contributing to her enduring legacy and critical re-evaluation.

- 1967: New Documents. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- 1972: Diane Arbus Portfolio: 10 Photos. Venice Biennale.

- 1972-1975: Diane Arbus (125 photographs, curated by John Szarkowski). Museum of Modern Art, New York; and traveling to Baltimore; Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Detroit Institute of Arts; Witte Memorial Museum, San Antonio, Texas; New Orleans Museum of Art; Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, California; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Florida Center for the Arts, University of South Florida, Tampa; and Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Champaign.

- 1973-1979: Diane Arbus: Retrospective (118 photographs, curated by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel). Seibu Museum, Tokyo; Hayward Gallery, London; Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, England; Scottish Arts Council, Edinburgh, Scotland; Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; Lenbachhaus Städtische Galerie, Munich, Germany; Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany; Frankfurter Kunstverein; 14 galleries and museums in Australia; and 7 galleries and museums in New Zealand.

- 1980: Diane Arbus: Vintage Unpublished Photographs. Robert Miller Gallery, New York; Fraenkel Gallery, New York.

- 1983: Diane Arbus: Photographs. Palazzo della Cento Finestre, Florence; Palazzo Fortuny, Venice; Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Milan.

- 1984-1987: Diane Arbus: Magazine Work 1960-1971. Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kansas; Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis; University of Kentucky Art Museum, Lexington; University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach; Neuberger Museum, State University of New York at Purchase; Wellesley College Museum, Massachusetts; and Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- 1986: Diane Arbus. American Center, Paris; La Fundacion "la Caixa", Barcelona, Spain; La Fundacion "la Caixa", Madrid; Robert Klein Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts; Light Factory, Charlotte, North Carolina.

- 1991: Diane Arbus. Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto.

- 1992: Diane Arbus: The Untitled Series, 1970-1971. Jan Kesner Gallery, Los Angeles.

- 1995: The Movies: Photographs from 1956 to 1958. Robert Miller Gallery, New York.

- 1997: Diane Arbus: Women. Galleria Photology, London.

- 2003-2006: Diane Arbus: Revelations. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; CaixaForum, Barcelona; and Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

- 2004-2005: Diane Arbus: Family Albums. Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts; Grey Art Gallery, New York; Portland Museum of Art, Maine; Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kansas; and Portland Art Museum, Oregon.

- 2005: Diane Arbus: Other Faces Other Rooms. Robert Miller Gallery, New York.

- 2007: Something Was There: Early Work by Diane Arbus. Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

- 2008-2009: Diane Arbus, a Printed Retrospective, 1960-1971. Kadist Art Foundation, Paris; and Centre Régional de la Photographie Nord Pas-de-Calais, Douchy-les-Mines, France.

- 2009: Diane Arbus. Timothy Taylor Gallery, London.

- 2009-2018: Artist Rooms: Diane Arbus. National Museum Cardiff, Wales; and Dean Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh; Nottingham Contemporary; Aberdeen Art Gallery; Tate Modern, London; Kirkcaldy Galleries; The Burton at Bideford.

- 2010: Diane Arbus: Christ in a Lobby and Other Unknown or Almost Known Works. Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin; FOAM, Amsterdam.

- 2011: Diane Arbus: People and Other Singularities. Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, California.

- 2011-2013: Diane Arbus. Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris; Fotomuseum, Winterthur; Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin; and Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam.

- 2016-2017: diane arbus: in the beginning. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco; Malba, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- 2013: Diane Arbus: 1971 - 1956. Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

- 2017: Diane Arbus: In the Park, Lévy Gorvy, New York.

- 2018: Diane Arbus: A Box of ten photographs, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- 2018: Diane Arbus Untitled, David Zwirner Gallery, New York.

- 2019: Diane Arbus: In the Beginning, Hayward Gallery, London.

- 2020: Diane Arbus: Photographs, 1956-1971, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

12. Collections

Diane Arbus's work is held in the permanent collections of numerous prestigious museums and art institutions worldwide.

- Akron Art Museum

- Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada

- Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

- BA-CA Kunstforum, Bank Austria Art Collection, Vienna

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

- Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama

- Center for Creative Photography, Tucson

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut

- Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland

- Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Poughkeepsie

- George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

- Goetz Collection, Munich

- Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- International Center of Photography, New York City

- Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, Valencia, Spain

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

- John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota

- Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, Michigan

- KMS Fine Art Group, Baar, Switzerland

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Maison Europeene de la Photographie, Paris

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Milwaukee Art Museum

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Moderna Museet Malmö

- Moderna Museet, Stockholm

- Morgan Library & Museum, New York

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California

- Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, Illinois

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

- Museum of Fine Arts (St. Petersburg, Florida)

- Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia

- National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

- New Orleans Museum of Art

- New York Public Library Main Branch, New York

- Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco, California

- The Progressive Art Collection, Mayfield Village

- Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence

- Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- Sweet Briar College Art Gallery, Sweet Briar, Virginia

- Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, UK (jointly held)

- Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Japan

- Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Whitney Museum, New York

- Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts

- Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto

- Yokohama Museum of Art, Yokohama, Japan