1. Life

James "Deacon" White's life spanned from the mid-19th century into the early 20th century, marked by his formative years in rural New York, his extensive professional baseball career, and his later life in Illinois with his family, maintaining a strong connection to his personal beliefs and community.

1.1. Early life and education

James Laurie White was born on December 2, 1847, in Caton, New York. His parents were Lester S. White, a farmer born around 1820, and Adeline, born around 1823. James was one of at least eight children in the family, including Oscar Leroy (born c. 1844), Elmer Melville (born c. 1851), William (1854-1911), Phebe Davis (born c. 1856), Estelle (born c. 1858), George (born c. 1862, who survived James), and Hattie (born c. 1867). The family also adopted a girl named Phebe Maynard (born c. 1876) when James's parents were in their fifties. White's ancestors likely immigrated to America during the Colonial period, with his grandparents reportedly born in New York or Pennsylvania in the late 18th or early 19th century. His cousin, Elmer White, also played professional baseball and was a teammate of James in 1871. Tragically, Elmer was the first recorded professional baseball player to die, in March 1872.

1.2. Personal life

On April 24, 1871, White married Marium Van Arsdale, who was born in 1851 in Moravia, New York. For a significant portion of his baseball career, they resided on his farm in Corning, New York. Following his move to the Buffalo Bisons in 1881, the family relocated to Buffalo. Their only child, Grace Hughson White, was born in Buffalo on September 8, 1882. The family briefly moved to Detroit when White played for the Wolverines but soon returned to Buffalo, where by 1900, White was successfully operating a livery stable.

After 1900, the Whites sent their daughter Grace to Mendota College in Mendota, Illinois, initiating a long-standing family connection with the Advent Christian school. By 1909, James and Marium themselves moved to Mendota, where they served as the head residents at Maple Hall, the young ladies' dormitory, until 1912. On August 15, 1912, Grace married Roger A. Watkins, a fellow Mendota alumnus, at the dormitory. That same year, the college relocated approximately 50 mile to the east and became Aurora College. Marium died on April 30, 1914, in Mendota. A student at Aurora College fondly remembered "Ma" White for her cheerful disposition, kindness, and personal interest in each girl, noting her words: "I am only doing what I would like to have some one else do for my girl, if she were away from home." Roger and Grace Watkins remained deeply involved with the college, moving to Aurora in 1920. Roger joined the college's board of directors in 1927, serving until 1971, and also as the board's secretary for most of that period. By 1930, Deacon White had remarried to Alice and moved into the Watkins' home at 221 Calumet Avenue, adjacent to the college president's residence.

2. Baseball Career

James "Deacon" White's baseball career spanned over two decades, establishing him as one of the most prominent players of the early professional era, excelling across multiple leagues and positions while also advocating for players' rights.

2.1. Early career (1868-1870s)

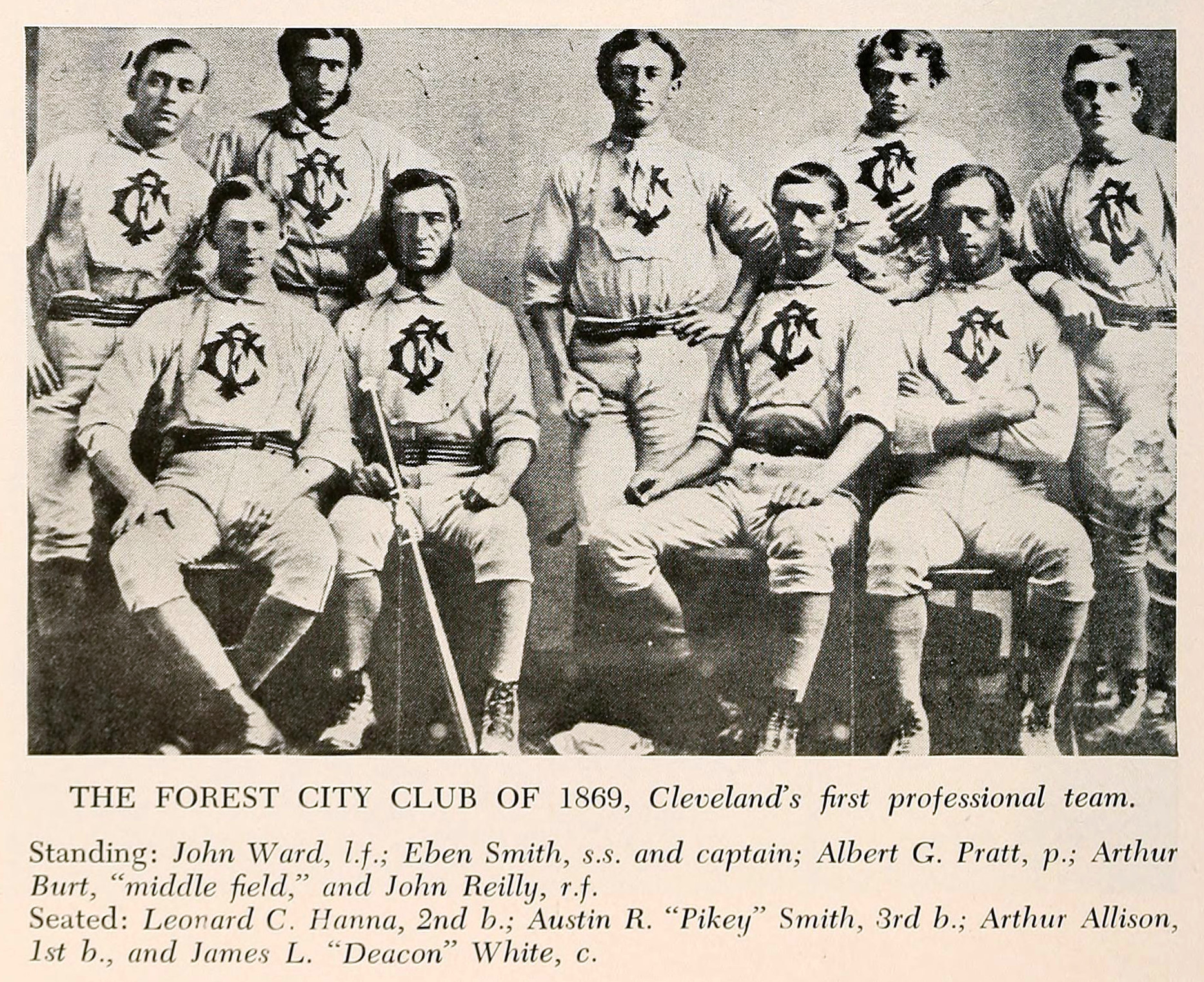

White's entry into baseball began after the American Civil War, when he learned the sport from a Union Army soldier who returned to his hometown in 1865. His professional career officially commenced in 1868 with the Cleveland Forest Citys club, a time when professional players were not yet the sole composition of teams.

White made history on May 4, 1871, by becoming the first batter to come to the plate in the National Association (NA), which was the first fully professional baseball league. In that inaugural game, he hit the first double off Bobby Mathews of the Fort Wayne Kekiongas in the first inning and also made the league's first catch. During his two seasons with the Cleveland Forest Citys (1871-1872), he maintained a batting average above .300. After the Forest Citys disbanded, White was invited by Harry Wright to join the Boston Red Stockings (now the Atlanta Braves) in 1873. With Boston, he quickly became a pivotal player, leading the NA in RBI with 77 and batting .390 in his third year (1873). In 1875, he achieved the league's highest batting average at .367, playing a crucial role in Boston's consecutive league championships. White's early career also saw him play against the undefeated Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869, baseball's first all-professional team. He was widely regarded as the best barehanded catcher of his era.

2.2. National League era

In 1876, with the formation of the National League, White joined the Chicago White Stockings (now the Chicago Cubs) for one season. Alongside teammates such as Albert Spalding, Cap Anson, and Ross Barnes, White was a key contributor to Chicago's inaugural National League championship. That year, he led the league with 60 RBI, becoming the NL's first official RBI leader. The following year, 1877, White returned to the Boston Red Stockings and once again led his team to a league championship. In a remarkable season where he primarily played first base, he topped the league in four major offensive categories: batting average (.387), hits (103), RBI (49), and triples (11), also leading in total bases and slugging percentage.

2.3. Later career and team changes

After his successful tenure with the Boston Red Stockings, James White spent three years with the Cincinnati Reds, where he played alongside his younger brother, Will White, a successful pitcher. Following his time in Cincinnati, White played five seasons for the Buffalo Bisons. In the offseason of 1885, when the Bisons disbanded, White and three other prominent players-Dan Brouthers, Hardy Richardson, and Jack Rowe-collectively known as the "Big Four," were transferred to the Detroit Wolverines for 7.00 K USD. This significant acquisition bolstered the Wolverines, leading them to win the 1887 World Series championship.

However, the baseball landscape of the late 1880s was marked by increasing disputes between players and team owners over contracts and player rights. In 1888, following the Wolverines' financial struggles, the team unilaterally sold the contracts of White and Jack Rowe to the Pittsburgh Alleghenys (now the Pittsburgh Pirates). White and Rowe refused to report to Pittsburgh unless they received additional compensation, leading to a prolonged legal battle. White famously stated to a reporter, "We appreciate the money, but we ain't worth it. Rowe's arm is gone. I'm over 40 and my fielding ain't so good, though I can still hit some. But I will say this. No man is going to sell my carcass unless I get half." This type of grievance was a significant factor in the formation of the Players' League in 1890, an independent league established by players to gain more control over their careers. White, at 42 years old, joined the Buffalo Bisons of the Players' League, playing in 122 games before retiring from professional baseball at the end of the 1890 season.

After his playing career, White briefly managed the minor league club Elmira Gladiators in the New York-Pennsylvania League in 1891. It is important to note that he has been incorrectly credited with managing the McAlester Miners (1907) of the Oklahoma-Arkansas-Kansas League and the Tulsa Oilers (1908) of the Oklahoma-Kansas League; both teams were actually managed by a different individual named Harry B. "Deacon" White.

2.4. Playing positions and statistics

James "Deacon" White was renowned for his versatility and skill across multiple positions. He began his career as an exceptional barehanded catcher, a position he played more than any other player in the 1870s. As the physical demands of catching increased with age, he transitioned to an effective third baseman in his mid-30s, where he continued to excel.

His career statistics highlight his consistent offensive prowess and defensive reliability. Over a 20-year period from 1871 to 1890, White maintained a career batting average of 0.312. He accumulated 988 RBI, a total surpassed only by Cap Anson at the time of his retirement. He also ranked among the all-time leaders in various offensive categories, including 1,560 career games, 6,624 at-bats, 2,067 hits, and 2,595 total bases. Defensively, at third base, he ranked fourth in career total chances (3,016), fifth in assists (1,618), and sixth in putouts (954) and double plays (118). White secured two batting titles (1875 and 1877) and led his league in RBI three times (1873, 1876, and 1877). Notably, it was not until 1953, when Roy Campanella led the National League, that another catcher would lead his league in RBI, underscoring White's unique achievement.

Below is a detailed breakdown of his annual batting statistics:

| Year | Team | League | Games | Plate Appearances | At Bats | Runs | Hits | Doubles | Triples | Home Runs | Total Bases | RBI | Stolen Bases | Caught Stealing | Sacrifice Hits | Sacrifice Flies | Walks | Hit By Pitch | Strikeouts | Double Plays | Batting Average | On-Base Percentage | Slugging Percentage | OPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871 | CFC | NA | 29 | 150 | 146 | 40 | 47 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 66 | 21 | 2 | 2 | - | - | 4 | - | - | 1 | 0 | .322 | .340 | .452 | .792 |

| 1872 | CFC | NA | 22 | 113 | 109 | 21 | 37 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 43 | 22 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 4 | - | - | 1 | 0 | .339 | .363 | .394 | .757 |

| 1873 | BSN | NA | 60 | 311 | 311 | 79 | 122 | 17 | 8 | 1 | 158 | 77 | 19 | 3 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 2 | 1 | .392 | .392 | .508 | .900 |

| 1874 | BSN | NA | 70 | 357 | 352 | 75 | 106 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 134 | 52 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 5 | - | - | 0 | 5 | .301 | .311 | .381 | .692 |

| 1875 | BSN | NA | 80 | 374 | 371 | 76 | 136 | 23 | 3 | 1 | 168 | 60 | 2 | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | - | 2 | 2 | '.367' | .372 | .453 | .824 |

| 1876 | CHC | NL | 66 | 310 | 303 | 66 | 104 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 127 | 60 | - | - | - | - | 7 | - | - | 3 | - | .343 | .358 | .419 | .777 |

| 1877 | BSN | NL | 59 | 274 | 266 | 51 | 103 | 14 | 11 | 2 | 145 | 49 | - | - | - | - | 8 | - | - | 3 | - | '.387' | .405 | '.545' | '.950' |

| 1878 | CIN | NL | 61 | 268 | 258 | 41 | 81 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 87 | 29 | - | - | - | - | 10 | - | - | 5 | - | .314 | .340 | .337 | .677 |

| 1879 | CIN | NL | 78 | 339 | 333 | 55 | 110 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 141 | 52 | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | 9 | - | .330 | .342 | .423 | .766 |

| 1880 | CIN | NL | 35 | 150 | 141 | 21 | 42 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 50 | 7 | - | - | - | - | 9 | - | - | 7 | - | .298 | .340 | .355 | .695 |

| 1881 | BUF | NL | 78 | 328 | 319 | 58 | 99 | 24 | 4 | 0 | 131 | 53 | - | - | - | - | 9 | - | - | 8 | - | .310 | .329 | .411 | .740 |

| 1882 | BUF | NL | 83 | 352 | 337 | 51 | 95 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 115 | 33 | - | - | - | - | 15 | - | - | 16 | - | .282 | .313 | .341 | .654 |

| 1883 | BUF | NL | 94 | 414 | 391 | 62 | 114 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 138 | 47 | - | - | - | - | 23 | - | - | 18 | - | .292 | .331 | .353 | .684 |

| 1884 | BUF | NL | 110 | 484 | 452 | 82 | 147 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 200 | 74 | - | - | - | - | 32 | - | - | 13 | - | .325 | .370 | .442 | .812 |

| 1885 | BUF | NL | 98 | 416 | 404 | 54 | 118 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 136 | 57 | - | - | - | - | 12 | - | - | 11 | - | .292 | .313 | .337 | .649 |

| 1886 | DTN | NL | 124 | 522 | 491 | 65 | 142 | 19 | 5 | 1 | 174 | 76 | 9 | - | - | - | 31 | - | 9 | 35 | - | .289 | .331 | .354 | .686 |

| 1887 | DTN | NL | 111 | 484 | 449 | 71 | 136 | 20 | 11 | 3 | 187 | 75 | 20 | - | - | - | 26 | - | 9 | 15 | - | .303 | .353 | .416 | .770 |

| 1888 | DTN | NL | 125 | 557 | 527 | 75 | 157 | 22 | 5 | 4 | 201 | 71 | 12 | - | - | - | 21 | - | 9 | 24 | - | .298 | .336 | .381 | .717 |

| 1889 | PIT | NL | 55 | 245 | 225 | 35 | 57 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 69 | 26 | 2 | - | - | - | 16 | - | 4 | 18 | - | .253 | .314 | .307 | .621 |

| 1890 | BUF | PL | 122 | 525 | 439 | 62 | 114 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 135 | 47 | 3 | - | - | - | 67 | - | 19 | 30 | - | .260 | .381 | .308 | .688 |

| Career: 20 years | 1560 | 6973 | 6624 | 1140 | 2067 | 270 | 98 | 24 | 2605 | 988 | 70 | 9 | - | - | 308 | 41 | 221 | 8 | .312 | .346 | .393 | .740 | |||

- Note: "-" indicates no record.

- Bold numbers indicate league leader for that season.

- Asterisk (*) in career totals indicates incomplete data for certain categories across all years.

White also had a brief pitching career, appearing in two games with a total of 10.0 innings, 3 strikeouts, and an earned run average of 7.20. As a player-manager, he had two stints: in 1872 with the Cleveland Forest Citys (2 games, 0 wins, 2 losses) and in 1879 with the Cincinnati Reds (18 games, 9 wins, 9 losses).

2.5. Player advocacy

Beyond his on-field achievements, James White was a significant figure in the early advocacy for players' rights in professional baseball. He actively participated in the formation of early player unions, which sought to address grievances such as the reserve clause, which bound players to their teams indefinitely, and owners' unilateral control over player contracts and salaries. His outspokenness, particularly during his contract dispute with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in 1889, where he and teammate Jack Rowe refused to report after their contracts were sold without their consent, highlighted the need for greater player autonomy. White's strong stance and his quote about being sold ("No man is going to sell my carcass unless I get half") underscored the prevailing sentiment among players that they were being treated as property rather than partners in the game. His involvement and contributions to these early efforts were instrumental in paving the way for the establishment of the Players' League in 1890, which aimed to give players more control and better compensation. White's long and respected career, combined with his principled character, earned him considerable respect from many of his peers, making him an influential voice in the nascent movement for player rights.

3. Beliefs and Philosophy

James "Deacon" White's character was shaped by a unique set of personal convictions that stood out during his professional baseball career, particularly his devout faith and an unconventional scientific belief.

3.1. Personal beliefs

White was known for his deeply held personal beliefs and a disciplined lifestyle that contrasted with the often rough-and-tumble environment of 19th-century baseball. He was a devoutly religious man, earning him the nickname "Deacon." He reportedly carried a Bible and was a regular churchgoer. In an era when tobacco use was common, White was a non-smoker, maintaining a temperate and respectable demeanor. His physical appearance, described as long-faced with a "walrus-like" mustache, reportedly made him seem less like a professional baseball player and more like a man of the cloth.

Perhaps his most notable and controversial personal belief was his conviction that the Earth is flat. According to historian Lee Allen in his 1961 book The National League Story, White firmly believed in a flat Earth and actively attempted to convince his teammates of this theory, often facing ridicule. Despite the skepticism, he was reportedly capable of constructing arguments that could persuade at least one teammate, though these arguments did not necessarily prove the Earth was not a sphere, but rather that it was not turning. This unusual belief remained a defining, if peculiar, aspect of his character throughout his life.

4. Death

James "Deacon" White died in the early morning of July 7, 1939, at the age of 91. He passed away at the summer cottage of his daughter Grace and son-in-law Roger Watkins, located at Rude Camp, Aurora College's retreat on the Fox River in St. Charles Township. Despite having been in generally good health, his death was attributed to a disastrous heat wave that affected the area at the time.

White had been scheduled to be the principal guest of honor at Aurora's celebration of baseball's centennial the very next day. Instead, the festivities transformed into a tribute to his memory. White had expressed considerable disappointment about not being invited to the opening ceremonies of the National Baseball Hall of Fame earlier that summer, having been completely overlooked in the initial voting for inductees. His funeral was held at Aurora's Healy Chapel, and he was laid to rest at Restland Cemetery in Mendota, Illinois. He was survived by his second wife, Alice, who was in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, at the time of his death, as well as by his younger brother George, his daughter Grace (1882-1956), and his son-in-law Roger Watkins (1888-1977).

5. Evaluation and Impact

James "Deacon" White's career is marked by exceptional skill and pioneering contributions to early professional baseball, though his personal beliefs also drew attention. His eventual induction into the Hall of Fame cemented his legacy as an overlooked giant of the game.

5.1. Positive evaluation

James "Deacon" White is widely recognized for his exceptional skills and significant contributions to the early professional game of baseball. He was considered the best barehanded catcher of his time, a remarkable feat given the lack of modern protective equipment. His transition to an effective third baseman later in his career further showcased his athletic adaptability and sustained performance. White's consistent offensive production, including two batting titles and three RBI titles, underscored his prowess at the plate. He was a key player on multiple championship teams in both the National Association and the National League, demonstrating his impact on team success. His long career allowed him to play alongside and influence many legendary figures of 19th-century baseball, earning him widespread respect among his peers. Beyond his statistics, White's character, marked by his devout faith and advocacy for players' rights, contributed to his respected status. He is now recognized as an overlooked pioneer whose achievements helped shape the foundational years of professional baseball.

5.2. Criticism and controversy

While James "Deacon" White was highly respected for his baseball skills and personal character, he is also remembered for a notable, albeit harmless, controversy: his steadfast belief in a flat Earth. This conviction, which he reportedly attempted to explain to his teammates, often led to ridicule. Despite his efforts to convince others, this belief remained a peculiar aspect of his personality that stood in contrast to the scientific understanding of his time. This particular belief, while not impacting his on-field performance or his overall contributions to the game, serves as a curious footnote in his biography.

5.3. Induction into the Hall of Fame

Despite his significant contributions to early professional baseball, James "Deacon" White's full recognition was delayed for many years after his retirement. In August 2008, he was named as one of ten former players whose careers began before 1943 to be considered by the Veterans Committee for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2009. Although he did not receive enough votes for induction that year, he garnered the most votes among players whose careers ended before 1940, indicating growing recognition of his overlooked legacy. In 2010, the Nineteenth Century Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) named White the year's "Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend," further highlighting his deservingness.

On December 3, 2012, the National Baseball Hall of Fame announced that White had been elected by the newly formed Pre-Integration Era Committee (covering the era before 1947). He received 14 out of 16 votes, securing his place among baseball's immortals. White, along with two other inductees elected by the committee, was formally inducted on July 28, 2013, in Cooperstown, New York. His acceptance speech was delivered by his great-grandson, Jerry Watkins. With over 166 years between his birth and the date of his induction, and nearly three-quarters of a century after his death, James "Deacon" White holds the distinction of being the "oldest" person ever inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6. Legacy and Impact

James "Deacon" White's legacy extends beyond his impressive statistics and pioneering play; his character and advocacy left a lasting influence on the sport of baseball and future generations of players.

6.1. Impact on later generations

James "Deacon" White's achievements, character, and advocacy have had a profound, though sometimes overlooked, influence on subsequent baseball players and the sport itself. As one of the principal stars during baseball's nascent professional era, his consistent high-level performance as both a catcher and a third baseman set a standard for versatility and durability. His role as the first batter in the National Association's history symbolically links him to the very genesis of professional league play.

Beyond his on-field prowess, White's unwavering personal integrity, exemplified by his devout faith and non-smoking habits, offered a contrasting image to the often rough-and-tumble reputation of 19th-century athletes. This aspect of his character, combined with his strong principles, earned him deep respect from his peers. Crucially, White's active involvement in advocating for players' rights and his participation in early player unions were foundational to the development of player collective action. His resistance to being unilaterally traded by owners, as seen in his dispute with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, highlighted the inequities faced by players and contributed directly to the formation of the Players' League. This advocacy helped lay the groundwork for future player movements that would eventually lead to greater rights and fairer compensation for athletes.

Although his contributions were long overlooked by the Baseball Hall of Fame, his eventual induction in 2013 solidified his place as a true pioneer. His story serves as a reminder of the early struggles and triumphs of professional baseball and the individuals who, through their talent and character, shaped its enduring legacy.