1. Overview

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (May 27, 1894 - January 10, 1961) was a pioneering American writer of hardboiled detective novels and short stories. He is widely recognized as one of the most significant figures in the development of the genre, establishing a distinctive style characterized by realism, authentic dialogue, and complex characters. Beyond his literary contributions, Hammett was a notable screenwriter and a dedicated political activist, particularly known for his left-wing views and anti-fascist stance. His work introduced iconic characters such as Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man, and The Continental Op in Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. Hammett's influence extended beyond literature, profoundly shaping mystery films, including the style known as film noir. Despite facing personal struggles and political persecution during the McCarthy era, his commitment to his principles and his groundbreaking literary achievements left an indelible mark on American literature and popular culture.

2. Life

Dashiell Hammett's life was marked by diverse experiences, from his humble beginnings and early employment to his service in two world wars and his eventual struggles with health and political blacklisting.

2.1. Early Life and Background

Samuel Dashiell Hammett was born on May 27, 1894, near Great Mills, Maryland, on the "Hopewell and Aim" farm in Saint Mary's County, Maryland. His father was Richard Thomas Hammett, and his mother was Anne Bond Dashiell, who came from an old Maryland family with a French surname, de Chiel, which had been Anglicized. He had an elder sister, Aronia, and a younger brother, Richard Jr. Known informally as Sam, Hammett was baptized a Catholic and spent his formative years growing up in Philadelphia and Baltimore. His family moved to Baltimore when he was four years old in 1898, and he primarily resided there until he permanently left in 1920 at the age of 26. Hammett attended the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute as a teenager, but his formal education concluded prematurely during his first year of high school. He dropped out in 1908, at the age of thirteen, due to his father's declining health and the pressing need for him to earn money to support his family.

2.2. Pinkerton Detective Agency and World War I Service

Before embarking on his writing career, Hammett held several odd jobs. His most significant early employment was with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, where he served as an operative from 1915 until February 1922. This period was interrupted by his service in World War I. While working for Pinkerton in Baltimore, he honed his investigative skills within the Continental Trust Building, now known as One Calvert Plaza. His experiences as a detective profoundly influenced his later writing, lending authenticity and realism to his fiction. However, his time with Pinkerton also led to disillusionment, particularly due to the agency's involvement in strike-breaking activities. He reportedly refused an order to kill a labor activist, who was later lynched, a traumatic event that contributed to his decision to leave the agency, though he later returned part-time due to financial necessity.

In 1918, Hammett enlisted in the United States Army Ambulance Service during World War I. During his service, he was afflicted with the Spanish flu epidemic and subsequently contracted tuberculosis. He spent most of his military tenure as a patient at Cushman Hospital in Tacoma, Washington. It was there that he met Josephine Dolan, a nurse, whom he married on July 7, 1921, in San Francisco.

2.3. Marriage and Family

Dashiell Hammett and Josephine Dolan had two daughters: Mary Jane, born in 1921, and Josephine, born in 1926. Shortly after the birth of their second child, health services nurses advised Dolan that, due to Hammett's tuberculosis, it was not advisable for her and the children to live with him full-time. Consequently, Dolan rented a separate home in San Francisco, where Hammett would visit on weekends. Although the marriage eventually dissolved, Hammett continued to provide financial support for his wife and daughters from the income he earned through his writing.

3. Literary Career

Hammett's literary career was foundational to the hardboiled detective genre, marked by his distinctive voice, realistic portrayal of crime, and creation of enduring characters.

3.1. Early Writing and Influence

Hammett's writing career began in 1922 with his first publication in The Smart Set magazine. He quickly gained recognition for the authenticity and realism of his prose, drawing heavily on his direct experiences as a Pinkerton operative. His time as a detective provided him with a unique insight into the criminal underworld and the gritty realities of investigation, which he masterfully translated into his fiction. Most of his detective stories were written while he resided in San Francisco during the 1920s, and the city's streets and landmarks frequently appear as settings in his narratives. Hammett famously stated, "I do take most of my characters from real life," underscoring his commitment to verisimilitude. His novels were among the first to employ dialogue that sounded genuinely authentic to the era, reflecting the terse, cynical, and often deceptive exchanges of his characters. This commitment to realism and his concise, report-like prose established his signature hardboiled style.

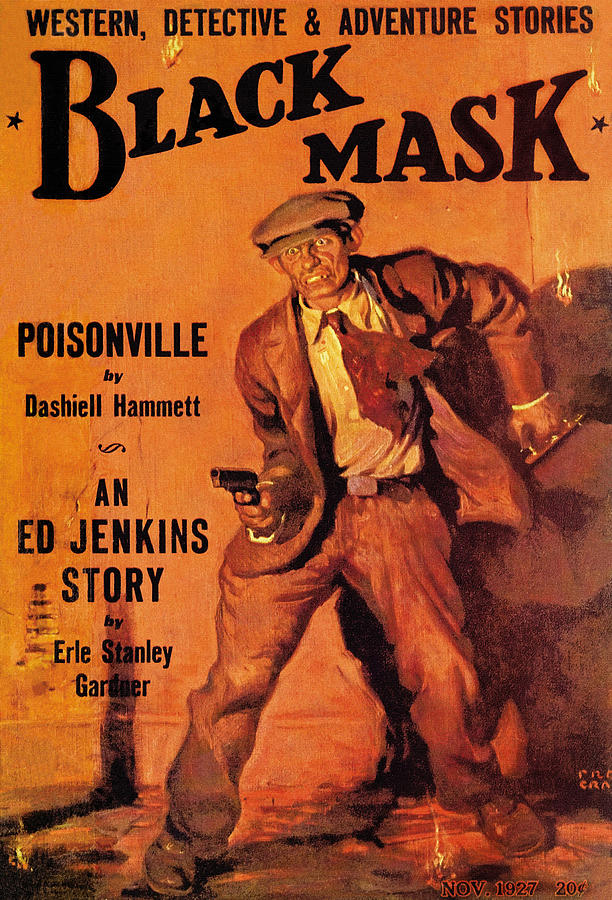

The majority of his early work, featuring a nameless private investigator known as The Continental Op, appeared in the prominent crime-fiction pulp magazine Black Mask. Hammett and the magazine both gained prominence during this period. A brief hiatus from Black Mask occurred in 1926 due to a financial dispute with editor Philip C. Cody. During this time, Hammett took a full-time position as an advertisement copywriter for the Albert S. Samuels Co., a San Francisco jeweler. He was later persuaded to return to Black Mask by its new editor, Joseph Thompson Shaw, to whom Hammett dedicated his first novel, Red Harvest. His second novel, The Dain Curse, was dedicated to Samuels.

3.2. Major Novels

Hammett authored five major novels, each contributing significantly to the hardboiled genre:

- Red Harvest (1929): This novel, dedicated to Joseph Thompson Shaw, depicts a private detective's attempt to clean up a corrupt, crime-ridden town called Poisonville. It is notable for its intense violence and cynical portrayal of justice. It has been widely influential, inspiring works like Akira Kurosawa's film Yojimbo and Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars.

- The Dain Curse (1929): Also featuring the Continental Op, this complex novel involves a convoluted mystery with elements of cults and psychological manipulation. It was dedicated to Albert S. Samuels.

- The Maltese Falcon (1930): Considered his masterpiece, this novel introduced the iconic private investigator Sam Spade. It is renowned for its objective, "camera-eye" style, where the narrative strictly adheres to what can be seen and heard, leaving character motivations to be inferred. The novel was dedicated to his wife, Josephine.

- The Glass Key (1931): This novel, dedicated to Nell Martin, features the gambler Ned Beaumont navigating a tangled web of political corruption and murder. Hammett himself considered this his favorite work, praised for its rigorous objectivity and portrayal of complex relationships.

- The Thin Man (1934): His final novel, dedicated to Lillian Hellman, introduced the sophisticated and witty husband-and-wife detective duo, Nick and Nora Charles. This book achieved significant popular success and led to a successful film series.

The French novelist André Gide highly praised Hammett, stating: "I regard his Red Harvest as a remarkable achievement, the last word in atrocity, cynicism and horror. Dashiell Hammett's dialogues, in which every character is trying to deceive all the others and in which the truth slowly becomes visible through a fog of deception, can be compared only with the best in Hemingway."

3.3. Short Stories and Key Characters

Hammett was a prolific writer of short stories, many of which were published in Black Mask magazine. His short fiction introduced and developed his most iconic characters.

The **Continental Op**, a nameless, portly private investigator working for the Continental Detective Agency, was featured in 28 stories and two serialized novels. These stories established Hammett's hardboiled style, characterized by terse prose, realistic violence, and a cynical worldview. All of his Continental Op stories, including an unfinished one, were later collected in their original unabridged forms in The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017).

- Sam Spade**, the protagonist of The Maltese Falcon, also appeared in three short stories: "A Man Called Spade", "Too Many Have Lived", and "They Can Only Hang You Once". An unfinished Sam Spade story, "A Knife Will Cut for Anybody", also exists. Spade is a tough, cynical, and morally ambiguous detective who operates outside the conventional boundaries of the law, relentlessly pursuing truth regardless of the cost.

- Nick and Nora Charles**, the charming and witty couple from The Thin Man, originated in the novel and were later featured in screen stories for film adaptations. A short story titled "A Man Named Thin" and an early draft of The Thin Man also exist.

3.4. Screenwriting and Other Writings

Beyond his novels and short stories, Hammett also ventured into screenwriting and other forms of writing. In early 1942, he wrote the screenplay for Watch on the Rhine, based on Lillian Hellman's successful play. The film received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, though it lost to Casablanca.

Before his literary breakthrough, Hammett worked as an advertisement copywriter for the Albert S. Samuels Co., a San Francisco jeweler. He also contributed articles on advertising to Western Advertising magazine, where he reviewed books monthly under the initial "S." for Samuel.

Hammett also contributed to the world of comic strips. From January 1934 to April 1935, he scripted the daily comic strip Secret Agent X-9, which was illustrated by Alex Raymond and syndicated by King Features Syndicate, appearing in most of William Randolph Hearst's newspapers.

Although he wrote his final novel, The Thin Man, in 1934, more than 25 years before his death, he sporadically continued to work on material. Lillian Hellman speculated that he stopped writing fiction because "he wanted to do new kind of work; he was sick for many of those years and getting sicker." She also suggested that he might have hoped for a fresh start and didn't want his old work to impede new endeavors.

4. Personal Relationships

Dashiell Hammett's life was significantly shaped by his personal relationships, particularly his romantic involvements with fellow writers.

For much of 1929 and 1930, Hammett was romantically involved with Nell Martin, a writer of short stories and several novels. He dedicated his novel The Glass Key to her, and in return, she dedicated her novel Lovers Should Marry to him.

In 1931, Hammett began a pivotal 30-year romantic relationship with the acclaimed playwright Lillian Hellman. Hellman was a strong-willed, witty, and intellectual woman with a wide social network, and her relationship with Hammett provided him with access to upper-class circles. Despite his struggles with excessive drinking and infidelity, which often strained their relationship, they remained close friends throughout their lives. In the 1940s, they resided together at Hellman's home, Hardscrabble Farm, in Pleasantville, New York. Their complex and enduring relationship was famously portrayed in the 1977 film Julia, where Jason Robards won an Oscar for his depiction of Hammett.

5. Political Activities and World War II Service

Dashiell Hammett dedicated a significant portion of his later life to political activism, driven by his strong convictions and experiences.

5.1. Political Stance and Beliefs

Hammett was deeply engaged in left-wing activism throughout his life. He was a staunch antifascist during the 1930s, and in 1937, he officially joined the Communist Party USA. His experiences as a Pinkerton detective, particularly witnessing the agency's role in suppressing labor strikes, fostered a strong empathy for the working class and a critical view of social injustice. He reportedly refused an order to kill a labor activist, an incident that fueled his disillusionment with the system and solidified his commitment to social justice.

In a letter dated November 25, 1937, to his daughter Mary, Hammett openly referred to himself and others as "we reds." While he acknowledged that "in a democracy all men are supposed to have an equal say in their government," he also believed that "their equality need not go beyond that." He further noted that "under socialism there is not necessarily... any leveling of incomes." Lillian Hellman described Hammett as "most certainly" a Marxist, albeit a "very critical Marxist" who was "often contemptuous of the Soviet Union" and "bitingly sharp about the American Communist Party", to which he nevertheless maintained loyalty.

5.2. League of American Writers Activities

Hammett was actively involved with the League of American Writers (1935-1943), a prominent organization whose members included Lillian Hellman, Alexander Trachtenberg, Frank Folsom, Louis Untermeyer, I. F. Stone, Myra Page, Millen Brand, Clifford Odets, and Arthur Miller. Many members were either Communist Party members or fellow travelers. In 1941, Hammett served as the president of the League.

His involvement with the League also included serving on its "Keep America Out of War Committee" in January 1940, during the period of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This anti-war stance shifted after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, leading the League to revise its position.

5.3. World War II Service

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor at the beginning of 1942, Hammett, despite being 48 years old, suffering from tuberculosis, and being a known Communist, made significant efforts to re-enlist in the United States Army. He later stated he had "a hell of a time" being inducted, though biographer Diane Johnson suggested that confusion over his forenames might have facilitated his re-enlistment.

He served as an enlisted man in the Aleutian Islands and initially worked on cryptanalysis on the island of Umnak. Due to concerns about his radical tendencies, he was transferred to the Headquarters Company, where he edited an Army newspaper titled The Adakian alongside Abraham Lincoln Brigade veteran Robert Garland Colodny. In 1943, while still in the military, he co-authored The Battle of the Aleutians with Corporal Colodny, under the direction of Major Henry W. Hall. During his time in the Aleutians, he developed emphysema.

After the war, Hammett returned to political activism, though with somewhat less fervor than before. On June 5, 1946, he was elected president of the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) at a meeting in New York City, and he dedicated a significant portion of his time to CRC activities.

6. Imprisonment and the Blacklist

Dashiell Hammett's political activism led to severe legal consequences and professional ostracization during the McCarthy era.

6.1. Civil Rights Congress Activities

In 1946, the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) established a bail fund "to be used at the discretion of three trustees to gain the release of defendants arrested for political reasons." Hammett served as the chairman of this fund, alongside Robert W. Dunn and Frederick Vanderbilt Field. The CRC was later designated a Communist front group by the United States Attorney General. Hammett also publicly endorsed Henry A. Wallace in the 1948 United States presidential election.

6.2. Contempt of Court and Imprisonment

The CRC's bail fund drew national attention on November 4, 1949, when it posted bail amounting to 260.00 K USD in negotiable government bonds to secure the release of eleven men appealing their convictions under the Smith Act. These men were convicted of criminal conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of the United States government by force and violence. On July 2, 1951, with their appeals exhausted, four of the convicted men fled rather than surrender to federal agents and begin serving their sentences. The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York issued subpoenas to the trustees of the CRC bail fund, including Hammett, in an attempt to ascertain the fugitives' whereabouts.

Hammett testified on July 9, 1951, before United States District Court Judge Sylvester Ryan, facing questioning from Irving H. Saypol, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, whom Time magazine described as "the nation's number-one legal hunter of top Communists." During the hearing, Hammett steadfastly refused to provide the information the government sought, specifically the list of contributors to the bail fund, "people who might be sympathetic enough to harbor the fugitives." He declined to answer every question regarding the CRC or the bail fund, invoking the Fifth Amendment, and even refused to identify his signature or initials on subpoenaed CRC documents. Immediately following his testimony, Hammett was found guilty of contempt of court.

He served time in a federal penitentiary in West Virginia. According to Lillian Hellman, he was assigned to clean toilets during his imprisonment. Hellman noted in her eulogy for Hammett that he chose to endure prison rather than reveal the names of the fund's contributors because "he had come to the conclusion that a man should keep his word." This principled stand, despite the personal cost, underscored his commitment to his beliefs.

6.3. Congressional Investigations and the Blacklist

During the 1950s, Hammett became a target of congressional investigations as part of Joseph McCarthy's efforts to uncover communist influence in American society. On March 26, 1953, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) regarding his own activities. Consistent with his earlier stance, he refused to cooperate with the committee. While no immediate official action was taken, his refusal led to his inclusion on the Hollywood blacklist, alongside many others who suffered professional ostracization during the era of McCarthyism.

By 1952, Hammett's public standing and financial situation had severely declined. He found himself impoverished due to a combination of factors: the cancellation of radio programs like The Adventures of Sam Spade and The Adventures of the Thin Man, and a substantial lien on his income by the Internal Revenue Service for back taxes owed since 1943. Furthermore, his books were no longer in print, and he was living off borrowed money. His works, including The Maltese Falcon, were even removed from government libraries due to his blacklisting.

7. Later Years and Death

Dashiell Hammett's final years were marked by a severe decline in health and a retreat from public life.

7.1. Health Decline and Later Life

Hammett had struggled with alcoholism even before his advertising career, and this addiction continued to plague him until 1948, when he finally quit under doctor's orders. However, years of heavy drinking and smoking exacerbated the tuberculosis he had contracted during World War I, and he later developed emphysema. According to Lillian Hellman, his imprisonment further weakened him, making "a thin man thinner, a sick man sicker... I knew he would now always be sick."

Hellman described Hammett as becoming "a hermit" during the 1950s. His decline was evident in the disarray of his rented "ugly little country cottage," where "signs of sickness were all around: now the phonograph was unplayed, the typewriter untouched, the beloved foolish gadgets unopened in their packages." He may have intended to embark on a new literary phase with the unfinished novel Tulip, but he left it incomplete, perhaps, as Hellman speculated, because he was "just too ill to care, too worn out to listen to plans or read contracts. The fact of breathing, just breathing, took up all the days and nights." Recognizing that he could no longer live alone, Hammett spent the last four years of his life with Hellman. She wrote that "not all of that time was easy, and some of it very bad," but she sought "something to have afterwards," anticipating his approaching death.

7.2. Death and Burial

Dashiell Hammett died in Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan on January 10, 1961, at the age of 66. The cause of death was lung cancer, which had been diagnosed just two months prior.

As a veteran of both world wars, Hammett was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Despite being a public figure who could have opted for a more prominent memorial, he chose a simple, unadorned headstone, identical to those of his fellow soldiers. This decision reflected his desire not to stand out among his comrades. His grave is located in section 12, site 508, within the cemetery.

8. Legacy and Influence

Dashiell Hammett's lasting impact on literature, film, and popular culture is profound, solidifying his status as a master of the crime genre.

8.1. Literary and Cultural Impact

Hammett is widely regarded as one of the best mystery writers of all time and the "dean of the 'hard-boiled' school of detective fiction." His foundational role in establishing the hardboiled genre is undeniable, characterized by his authentic dialogue, realistic portrayal of crime, and complex, often morally ambiguous characters. His influence extended to subsequent generations of writers, including Raymond Chandler, John D. MacDonald, and Ross Macdonald. Chandler, often considered Hammett's successor, summarized his accomplishments in his essay "The Simple Art of Murder":

"Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not with hand-wrought dueling pistols, curare, and tropical fish... He is said to have lacked heart, yet the story he thought most of himself [The Glass Key] is the record of a man's devotion to a friend. He was spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before."

His novels and stories had a significant influence on mystery films, particularly contributing to the style that became known as film noir. Time included his 1929 novel Red Harvest on its list of the 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005. The 1990 Crime Writers' Association picked three of his five novels for their list of The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time. Five years later, The Maltese Falcon placed second on The Top 100 Mystery Novels of All Time as selected by the Mystery Writers of America; Red Harvest, The Glass Key, and The Thin Man were also on the list.

His influence continues to resonate in popular culture. For example, Akira Kurosawa's 1961 film Yojimbo and Sergio Leone's 1964 film A Fistful of Dollars were notably influenced by Red Harvest. The 1975 film The Black Bird starred George Segal as Sam Spade, Jr., serving as a sequel and parody of The Maltese Falcon. The 1976 comedic film Murder by Death spoofed several famous literary sleuths, including Hammett's characters, with parodies like Sam Diamond and Dick and Dora Charleston. More recently, the main characters of Rachel Cohn's 2006 YA novel Nick & Norah's Infinite Playlist were named for the sleuths in Hammett's Thin Man series, leading to a 2008 film adaptation. Cohn and David Levithan later authored a series of YA suspenseful romance novels, starting with Dash & Lily's Book of Dares (2011), followed by The Twelve Days of Dash and Lily (2016) and Mind the Gap, Dash & Lily (2020), which were adapted into a Netflix television series.

8.2. Honors and Commemorations

Hammett's legacy is also honored through several literary prizes and biographical portrayals. The International Association of Crime Writers established the Dashiell Hammett International Crime Fiction Prize to recognize outstanding crime novels written in Spanish. The North American branch of the same association created the annual "The Hammett Prize" in 1992, awarded to the best crime novel by an American or Canadian author. The Scandinavian Crime Novel Society also established the Glass Key Award, named after Hammett's novel, to honor the best Nordic crime novel annually.

His life and relationships have been depicted in various films and documentaries:

- The 1977 film Julia portrayed his relationship with Lillian Hellman, with Jason Robards winning an Oscar for his depiction of Hammett and Jane Fonda nominated for her portrayal of Hellman.

- He was the subject of a 1982 prime-time PBS biography, The Case of Dashiell Hammett, which received a Peabody Award and a special Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Mystery Writers of America.

- Frederic Forrest portrayed Hammett semi-fictionally as the protagonist in the 1982 film Hammett, based on the novel by Joe Gores. Forrest reprised the role in the 1992 made-for-TV film Citizen Cohn.

- Sam Shepard played Hammett in the 1999 Emmy-nominated biographical television film Dash and Lilly, co-starring Judy Davis as Hellman.

9. Works

9.1. Novels

Hammett completed five major novels, all of which were first serialized in magazines before being published in book form:

- Red Harvest (1929)

- The Dain Curse (1929)

- The Maltese Falcon (1930)

- The Glass Key (1931)

- The Thin Man (1934)

9.2. Short Stories

Dashiell Hammett wrote over 80 complete and standalone short stories, many of which featured his iconic characters, the Continental Op and Sam Spade. These stories were predominantly published in pulp magazines, most notably Black Mask, where his hardboiled style was forged.

After their initial publication, most of Hammett's short stories were first collected in various digest-sized paperbacks by Mercury Publications under imprints such as Bestsellers Mystery, A Jonathan Press Mystery, or Mercury Mystery. These early collections, edited by Ellery Queen (Frederic Dannay), often presented abridged versions of the original stories. Some of these digests were later reprinted as hardcovers by World Publishing and as Dell mapbacks.

A significant collection, The Big Knockover and Other Stories (1966), edited by Lillian Hellman, played a crucial role in reviving Hammett's literary reputation in the 1960s and spurred a new wave of anthologies. However, many of these subsequent collections continued to use Dannay's abridged versions.

The first collection to print Hammett's stories in their original, unedited forms was Crime Stories & Other Writings (2001), edited by Steven Marcus. Subsequent collections that also feature the original texts include Lost Stories (2005), The Hunter and Other Stories (2013), and The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017). The forthcoming Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) is intended as the first volume of a complete edition of his short fiction, aiming for textual accuracy.

| Title | First Publication | Most Recent Collection | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| "The Parthian Shot" | The Smart Set, October 1922 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "Immortality" | 10 Story Book, November 1922 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Daghull Hammett |

| "The Barber and His Wife" | Brief Stories, December 1922 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson, the first story written by Hammett but was initially rejected. |

| "The Road Home" | Black Mask, December 1922 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson |

| "The Master Mind" | The Smart Set, January 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "The Sardonic Star of Tom Doody" | Brief Stories, February 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson, reprinted elsewhere as "Wages of Crime" |

| "The Vicious Circle" | Black Mask, June 15, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson, reprinted elsewhere as "The Man Who Stood in the Way" |

| "The Joke on Eloise Morey" | Brief Stories, June 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "Holiday" | The New Pearson's, July 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "The Crusader" | The Smart Set, August 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Mary Jane Hammett |

| "Arson Plus" | Black Mask, October 1, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson |

| "The Dimple" | Saucy Stories, October 15, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Reprinted elsewhere as "In the Morgue" |

| "Crooked Souls" | Black Mask, October 15, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Reprinted elsewhere as "The Gatewood Caper" |

| "Slippery Fingers" | Black Mask, October 15, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson |

| "The Green Elephant" | The Smart Set, October 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "It" | Black Mask, November 1, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Reprinted elsewhere as "The Black Hat That Wasn't There" |

| "The Second-Story Angel" | Black Mask, November 15, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "Laughing Masks" | Action Stories, November 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson, reprinted elsewhere as "When Luck's Running Good" |

| "Bodies Piled Up" | Black Mask, December 1, 1923 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Reprinted elsewhere as "House Dick" |

| "Itchy" | Brief Stories, January 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Written as Peter Collinson, reprinted elsewhere as "Itchy the Debonair" |

| "The Tenth Clew" | Black Mask, January 1, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Sometimes spelled "The Tenth Clue" |

| "The Man Who Killed Dan Odams" | Black Mask, January 15, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "Night Shots" | Black Mask, February 1, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "The New Racket" | Black Mask, February 15, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | Reprinted elsewhere as "The Judge Laughed Last" |

| "Esther Entertains" | Brief Stories, February 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "Afraid of a Gun" | Black Mask, March 1, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "Zigzags of Treachery" | Black Mask, March 1, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "One Hour" | Black Mask, April 1, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "The House in Turk Street" | Black Mask, April 15, 1924 | Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025) | |

| "The Girl with the Silver Eyes" | Black Mask, June 1924 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Women, Politics and Murder" | Black Mask, September 1924 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Reprinted elsewhere as "Death on Pine Street" and "A Tale of Two Women" |

| "The Golden Horseshoe" | Black Mask, November 1924 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Who Killed Bob Teal?" | True Detective Stories, November 1924 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Nightmare Town" | Argosy All-Story Weekly, December 27, 1924 | Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001) | |

| "Mike, Alec or Rufus?" | Black Mask, January 1925 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Reprinted elsewhere as "Tom, Dick or Harry?" |

| "Another Perfect Crime" | Experience, February 1925 | Lost Stories (2005) | |

| "The Whosis Kid" | Black Mask, March 1925 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Ber-Bulu" | Sunset Magazine, March 1925 | Lost Stories (2005) | Reprinted elsewhere as "The Hairy One" |

| "The Scorched Face" | Black Mask, May 1925 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Corkscrew" | Black Mask, September 1925 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Ruffian's Wife" | Sunset Magazine, October 1925 | Nightmare Town (1999) | |

| "Dead Yellow Women" | Black Mask, November 1925 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "The Glass That Laughed" | True Police Stories, November 1925 | Rediscovered in 2017 and published online by Electric Literature | |

| "The Gutting of Couffignal" | Black Mask, December 1925 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "The Nails in Mr. Cayterer" | Black Mask, January 1926 | The Creeping Siamese (1950) | |

| "The Assistant Murderer" | Black Mask, February 1926 | Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001) | Reprinted elsewhere as "First Aide to Murder" |

| "Creeping Siamese" | Black Mask, March 1926 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "The Advertising Man Writes a Love Letter" | Judge, February 26, 1927 | Lost Stories (2005) | |

| "The Big Knock-Over" | Black Mask, February 1927 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "$106,000 Blood Money" | Black Mask, May 1927 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "The Main Death" | Black Mask, June 1927 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "This King Business" | Mystery Stories, January 1928 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Fly Paper" | Black Mask, August 1929 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "The Farewell Murder" | Black Mask, February 1930 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "Death and Company" | Black Mask, November 1930 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | |

| "On the Way" | Harper's Bazaar, March 1932 | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | |

| "A Man Called Spade" | American Magazine, July 1932 | Nightmare Town (1999) | |

| "Too Many Have Lived" | American Magazine, October 1932 | Nightmare Town (1999) | |

| "They Can Only Hang You Once" | Collier's, November 19, 1932 | Nightmare Town (1999) | |

| "Woman in the Dark" (3 parts) | Liberty, April 8, 15, & 22, 1933 | Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001) | |

| "Night Shade" | Mystery League Magazine, October 1, 1933 | Lost Stories (2005) | |

| "Albert Pastor at Home" | Esquire, Autumn 1933 | Nightmare Town (1948) | |

| "Two Sharp Knives" | Collier's, January 13, 1934 | Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001) | Reprinted elsewhere as "To a Sharp Knife" |

| "His Brother's Keeper" | Collier's, February 17, 1934 | Nightmare Town (1999) | |

| "This Little Pig" | Collier's, March 24, 1934 | Lost Stories (2005) | |

| "A Man Named Thin" | Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, March 1961 | Nightmare Town (1999) | Written in the mid-1920s under the title "The Figure of Incongruity" but was not published until 1961. |

| "Seven Pages" | Discovering the Maltese Falcon and Sam Spade (2005) | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | |

| "Faith" | The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps (2007) | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | |

| Untitled | The Strand Magazine, Feb-May, 2011 under the title "So I Shot Him" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) under the title "The Cure" | |

| "The Hunter" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "The Sign of the Potent Pills" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "Action and the Quiz Kid" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "Fragments of Justice" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "A Throne for the Worm" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "Magic" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "An Inch and a Half of Glory" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "Nelson Redline" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "Monk and Johnny Fox" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "The Breech-Born" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "The Lovely Strangers" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "Week-End" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | ||

| "The Man Who Loved Ugly Women" | Experience, date unknown | Lost |

| Title | First Publication | Most Recent Collection | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| "The Cleansing of Poisonville" | Black Mask, November 1927 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into Red Harvest |

| "Crime Wanted-Male or Female" | Black Mask, December 1927 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into Red Harvest |

| "Dynamite" | Black Mask, January 1928 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into Red Harvest |

| "The 19th Murder" | Black Mask, February 1928 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into Red Harvest |

| "Black Lives" | Black Mask, November 1928 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into The Dain Curse |

| "The Hollow Temple" | Black Mask, December 1928 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into The Dain Curse |

| "Black Honeymoon" | Black Mask, January 1929 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into The Dain Curse |

| "Black Riddle" | Black Mask, February 1929 | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Later reworked into The Dain Curse |

| "The Maltese Falcon" (part 1 of 5) | Black Mask, September 1929 | The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010) | Later reworked into The Maltese Falcon |

| "The Diamond Wager" | Detective Fiction Weekly, October 19, 1929 | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | Written by Samuel Dashiell, who is long thought to be Dashiell Hammett, but Hammett's authorship is rejected by Will Murray. |

| "The Maltese Falcon" (part 2 of 5) | Black Mask, October 1929 | The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010) | Later reworked into The Maltese Falcon |

| "The Maltese Falcon" (part 3 of 5) | Black Mask, November 1929 | The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010) | Later reworked into The Maltese Falcon |

| "The Maltese Falcon" (part 4 of 5) | Black Mask, December 1929 | The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010) | Later reworked into The Maltese Falcon |

| "The Maltese Falcon" (part 5 of 5) | Black Mask, January 1930 | The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010) | Later reworked into The Maltese Falcon |

| "The Glass Key" | Black Mask, March 1930 | Later reworked into The Glass Key | |

| "The Cyclone Shot" | Black Mask, April 1930 | Later reworked into The Glass Key | |

| "Dagger Point" | Black Mask, May 1930 | Later reworked into The Glass Key | |

| "The Shattered Key" | Black Mask, June 1930 | Later reworked into The Glass Key | |

| "The Thin Man" | Redbook, December 1933 | A condensed version of the novel | |

| "The Thin Man and the Flack" | Click, December 1941 | Lost Stories (2005) | Photo story |

| "Tulip" | The Big Knockover (1966) | Unfinished novel fragment | |

| First draft of "The Thin Man" | City of San Francisco, Dashiell Hammett Special Issue, November 4, 1975 | Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001) under the title "The Thin Man: an Early Typescript" | Also reprinted in Nightmare Town (1999) under the title "The First Thin Man" |

| "After the Thin Man" (2 parts) | The New Black Mask, no. 5 & 6, 1986 | Return of the Thin Man (2012) | Screen story for After the Thin Man (1936) |

| "Another Thin Man" | Return of the Thin Man (2012) | Screen story for Another Thin Man (1939) | |

| "Sequel to the Thin Man" | Return of the Thin Man (2012) | Screen story, unproduced | |

| "The Kiss-Off" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | Screen story for City Streets (1931) | |

| "Devil's Playground" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | Screen story, unproduced | |

| "On the Make" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | Screen story for Mister Dynamite (1935) | |

| "A Knife Will Cut for Anybody" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) | Unfinished Sam Spade story | |

| "The Secret Emperor" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) ebook bonus | Unfinished fragment | |

| "Time to Die" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) ebook bonus | Unfinished fragment | |

| "September 20, 1938" | The Hunter and Other Stories (2013) ebook bonus | Unfinished fragment | |

| "Three Dimes" | The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) | Unfinished Continental Op story |

9.2.1. Short Stories Grouped by Characters

The **Continental Op**, a nameless, portly private investigator working for the Continental Detective Agency, was featured in 28 stories and two serialized novels. All 28 Continental Op stories and one unfinished story have been collected in their original unabridged forms in The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017).

- Sam Spade**, the protagonist of The Maltese Falcon, appeared in:

9.3. Other Writings

Beyond his fiction, Hammett's other notable writings include:

- Screenplays**:

- Watch on the Rhine (1943), based on Lillian Hellman's play.

- Screen Stories** (some produced, some unproduced):

- "The Kiss-Off" (for City Streets, 1931)

- "Devil's Playground" (unproduced)

- "On the Make" (for Mister Dynamite, 1935)

- "After the Thin Man" (for After the Thin Man, 1936)

- "Another Thin Man" (for Another Thin Man, 1939)

- "Sequel to the Thin Man" (unproduced)

- Articles**:

- "The Great Lovers" (The Smart Set, 1922)

- "From the Memoirs of a Private Detective" (The Smart Set, 1923)

- "In Defence of the Sex Story" (The Writer's Digest, 1924)

- "Three Favorites" (Black Mask, 1924)

- "Vamping Sampson" (The Editor, 1925)

- Articles on advertising, including "The Advertisement IS Literature" (Western Advertising, 1926) and "Advertising Art Isn't Art -- It's Advertising" (Western Advertising, 1927).

- Letters**: A collection of his correspondence was published as Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett: 1921-1960 (2001).

- Daily Comic Strips**:

- Secret Agent X-9 (January 1934 - April 1935), with scripts by Hammett and illustrations by Alex Raymond. Collections include Secret Agent X-9 Book 1 (1934) and Secret Agent X-9 (2015).

- Edited Anthologies**:

- Creeps by Night; Chills and Thrills (1931), an anthology of horror stories edited by Hammett.

- Military Publications**:

- The Battle of the Aleutians (1944), a pamphlet co-authored with Cpl. Robert Colodny.

10. Collections

10.1. Novels (Collections)

- The Dashiell Hammett Omnibus (1935) - Includes Red Harvest, The Dain Curse, and The Maltese Falcon.

- The Complete Dashiell Hammett (1942)

- Dashiell Hammett's Mystery Omnibus (1944) - Includes The Maltese Falcon and The Glass Key.

- The Novels of Dashiell Hammett (1965)

- Dashiell Hammett: Five Complete Novels (1980)

- Complete Novels (1999)

- The Dain Curse: The Glass Key; and Selected Stories (2007)

10.2. Short Fiction (Collections)

After their initial publication in pulp magazines, most of Hammett's short stories were first collected in ten digest-sized paperbacks by Mercury Publications under an imprint, either Bestsellers Mystery, A Jonathan Press Mystery or Mercury Mystery. The stories were edited by Ellery Queen (Frederic Dannay) and were abridged versions of the original publications. Some of these digests were reprinted as hardcovers by World Publishing under the imprint Tower Books. The anthologies were also republished as Dell mapbacks. An important collection, The Big Knockover and Other Stories, edited by Lillian Hellman, helped revive Hammett's literary reputation in the 1960s and fostered a new series of anthologies. However, most of these used Dannay's abridged version of the stories.

The first collection that prints stories in their original unedited forms is Crime Stories & Other Writings (2001) edited by Steven Marcus (especially after the third printing that incorporates the original text of This King Business). Subsequent collections that print the original texts include Lost Stories (2005), The Hunter and Other Stories (2013), and The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017).

10.2.1. Mercury Publications

- $106,000 Blood Money (1943). Collection of two connected Continental Op stories, "The Big Knockover" and "$106,000 Blood Money".

- The Adventures of Sam Spade (1944). Collection of three Spade stories and four others.

- They Can Only Hang You Once and Other Stories (1949). Reprint of Bestseller Mystery B50.

- The Continental Op (1945). Collection of four Continental Op stories.

- The Continental Op (1949). Reprint of Bestseller Mystery B62.

- The Return of the Continental Op (1945). Collection of five further Continental Op stories.

- Hammett Homicides (1946). Collection of six stories, four of which feature the Continental Op.

- Dead Yellow Women (1947). Collection of six stories, four of which feature the Continental Op.

- Nightmare Town (1948). Collection of four stories, two of which feature the Continental Op.

- The Creeping Siamese (1950). Collection of six stories, three of which feature the Continental Op.

- Woman in the Dark (1951). Collection of the three part novelette.

- A Man Named Thin (1962). Collection of eight stories, one of which features the Continental Op.

10.2.2. World Publishing

- Blood Money (1943). Hardcover edition of Bestseller Mystery B40.

- The Adventures of Sam Spade and other stories (1945). Hardcover edition of Bestseller Mystery B50.

10.2.3. Dell

- Blood Money (1944). Mapback reprint of Bestseller Mystery B40.

- Blood Money (1951). Mapback reprint of Bestseller Mystery B40.

- A Man Called Spade and Other Stories (1945). Mapback reprint of Bestseller Mystery B50 but omits two stories: Nightshade and The Judge Laughed Last.

- A Man Called Spade and Other Stories (1950). Reprint of Dell #90.

- A Man Called Spade and Other Stories (1952). Reprint of Dell #90.

- The Continental Op (1946). Reprint of Bestseller Mystery B62.

- The Return of the Continental Op (1947). Reprint of Jonathan Press Mystery J17.

- Hammett Homicides (1948). Mapback reprint of Bestseller Mystery B81.

- Dead Yellow Women (1949). Mapback reprint of Jonathan Press Mystery J29.

- Dead Yellow Women (1950). Mapback reprint of Jonathan Press Mystery J29.

- Nightmare Town (1950). Mapback reprint of Mercury Mystery #120.

- The Creeping Siamese (1951). Mapback reprint of Jonathan Press Mystery J48, 1950.

10.2.4. Later collections

Along with the novels, these later collections have been reprinted in paperback versions under many imprints: Vintage Crime, Black Lizard, Everyman's library.

- The Big Knockover (1966). Including the unfinished novel Tulip.

- The Continental Op (1974). Edited and with an introduction by Steven Marcus. Comprises 7 stories.

- Woman in the Dark (1988). Hardcover collection of the three parts of the title novelette, with an introduction by Robert B. Parker.

- Nightmare Town (1999). Hardcover collection, with contents different from the digest of the same title.

- Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001), edited by Steven Marcus.

- Lost Stories (2005). Collection of 21 stories not been previously published in hardcover, including some previously unpublished stories, with several long commentaries on Hammett's career providing context for the stories. Introduction by Joe Gores.

- Vintage Hammett (2005). Collection nine stories of Sam Spade, Nick and Nora Charles, and The Continental Op.

- The Hunter and Other Stories (2013). Collection of previously unpublished or uncollected stories and screenplays, including a fragment of a second Sam Spade novel. Edited by Richard Layman and Julie M. Rivett.

- The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010). Reprints The Maltese Falcon in its original serialized form.

- The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017). Collects all twenty-eight stories and two serialized novels starring Continental Op, plus the previously unpublished fragment "Three Dimes."

- Collected Stories: Volume 1: 1922-1924 (2025). First volume of the complete edition of Hammett's short fiction (including novelettes and novellas) and the first edition to print Hammett's stories in textually accurate form. Edited by S. T. Joshi.

10.2.5. Daily comic strips (Collections)

- Secret Agent X-9 Book 1 (1934). Collection of the comic strip written by Hammett and illustrated by Alex Raymond.

- Secret Agent X-9 Book 2 (1934). A second collection of the comic strip.

- Secret Agent X-9 (1976).

- Dashiell Hammett's Secret Agent X-9 (1983).

- Secret Agent X-9 (1990).

- Secret Agent X-9 (2015). Collection of the comic strip written by Hammett and Leslie Charteris and illustrated by Alex Raymond.

11. Adaptations

11.1. Film

11.1.1. Film Adaptations

Many of Hammett's novels and stories were adapted into films, some multiple times:

- Roadhouse Nights (1930), an adaptation of Red Harvest.

- The Maltese Falcon (1931) and Satan Met a Lady (1936), both early adaptations of The Maltese Falcon. The most famous adaptation is The Maltese Falcon (1941), directed by John Huston and starring Humphrey Bogart, which became a classic of film noir.

- Woman in the Dark (1934).

- The Thin Man (1934), which launched a successful film series starring William Powell and Myrna Loy.

- The Glass Key (1935) and The Glass Key (1942).

- No Good Deed (2002), an adaptation of his short story "The House in Turk Street".

11.1.2. Films Based on Characters

- The Fat Man (1951).

- Sequels to The Thin Man: After the Thin Man (1936), Another Thin Man (1939), Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), The Thin Man Goes Home (1945), and Song of the Thin Man (1947).

- Serial adaptations of Secret Agent X-9: Secret Agent X-9 (1937) and Secret Agent X-9 (1945).

11.2. Radio

11.2.1. Radio Adaptations

Hammett's stories and characters were widely popular on radio, leading to numerous adaptations:

- Adaptations of his novels: The Thin Man (Lux Radio Theatre, 1936; 1940), The Glass Key (The Campbell Playhouse, 1939; Hour of Mystery, 1946; The Screen Guild Theater, 1946), and multiple adaptations of The Maltese Falcon (Silver Theater, 1942; Philip Morris Playhouse, 1942; Lux Radio Theatre, 1943; The Screen Guild Theater, 1943; Academy Award Theatre, 1946).

- Adaptations of short stories: "Two Sharp Knives" (Suspense, 1942; 1945).

- Radio drama of his comic strip: Dashiell Hammett - Secret Agent X-9 (BBC Radio 5, 1994).

11.2.2. Radio Series Based on Characters

- The Thin Man (NBC, 1941; CBS, 1946; NBC, 1948; ABC, 1950).

- The Adventures of Sam Spade (CBS, 1946; NBC, 1949).

- The Fat Man (ABC, 1946-1950; Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 1954-1955).

11.3. Comic Book

- The Maltese Falcon (1946), Feature Book #48 by David McKay Publications for King Features Syndicate, featuring Hammett's original dialogue and art by Rodlow Willard.

11.4. Television

- "Two Sharp Knives" (Studio One, CBS, 1949).

- The Thin Man (MGM Television for NBC, 1957-1959), starring Peter Lawford and Phyllis Kirk.

- The Dain Curse (CBS, 1978), a TV mini-series starring James Coburn as the Continental Op.

- "Fly Paper" (Fallen Angels, Season 2, Episode 7, 1995), featuring Christopher Lloyd as the Continental Op.

12. Archives

Significant collections of Dashiell Hammett's papers, manuscripts, and correspondence are preserved in major archival institutions.

The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin holds a substantial collection of Hammett's papers. This archive includes his manuscripts, personal correspondence, and a small group of miscellaneous notes, providing valuable insights into his creative process and personal life.

The Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of South Carolina also houses the Dashiell Hammett family papers, offering further resources for researchers studying his life and work.