1. Early Life in Britain

Charles Edward's early life was rooted in the British royal family before his unexpected move to Germany, shaping his complex identity.

1.1. Family

Charles Edward was born into the extended British royal family. His father was Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, the youngest son of the reigning British monarch, Queen Victoria, and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Prince Leopold was described by historian Karina Urbach as "the most intellectual of Queen Victoria's children". Charles Edward's mother was Princess Helen of Waldeck and Pyrmont, daughter of the ruling Prince George Victor of Waldeck and Pyrmont and sister to Queen Emma of the Netherlands. Royal biographer Theo Aronson characterized Helen as a "capable, conscientious" and devout Christian woman. Prince Leopold, who suffered from haemophilia, tragically died after a fall and head injury months before Charles Edward's birth. Charles Edward, being a male child, was not at risk of inheriting haemophilia from his father.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the British royal family had fostered close familial ties with Protestant, particularly German, reigning families across Continental Europe. Queen Victoria's immediate family belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; her deceased husband, Prince Albert, was the younger brother of the childless Duke Ernest II. Ernest governed the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, a state within the German Empire. Victoria and Albert's eldest daughter, Victoria, Princess Royal, was the mother of German Emperor Wilhelm II. Their eldest son, Edward VII, was the heir apparent to the British throne. Consequently, their second son, Prince Alfred, succeeded his uncle Ernest II as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1893. The family's extensive connections across European monarchies led to Queen Victoria being widely known as the "Grandmother of Europe".

1.2. Childhood

Leopold Charles Edward George Albert was born on 19 July 1884 at Claremont House near Esher, Surrey, England. He primarily used the name Charles Edward. His father, Leopold, had wanted his firstborn son to be named after Charles Edward Stuart, an 18th-century claimant to the British throne. Charles Edward was privately baptized at Claremont on 4 August 1884 due to illness shortly after his birth; his baptism was publicly certified at St George's Church, Esher, on 4 December 1884. For the first 15 years of his life, Charles Edward was brought up as a British prince. He inherited his deceased father's titles at birth, becoming styled His Royal Highness the Duke of Albany, in addition to being the Earl of Clarence and Baron Arklow. He had one elder sister, Princess Alice, who was a year and a half his senior. Charles Edward was an intensely anxious child and frequently sought support from Alice, a habit that continued throughout his adulthood. The siblings were so close that they were nicknamed "Siamese twins".

The Albany household at Claremont House was described as "cosy, comfortable, well-ordered". After her husband's death, the British Parliament granted Helen an annual allowance of 6.00 K GBP from the civil list, which, while not making her as wealthy as during her marriage, allowed her to employ numerous domestic servants, including those responsible for the children. One of Charles Edward's childhood nannies described him as "delicate and sensitive, nervous and tiring". Medical experts believed his health was permanently affected by his widowed mother's grief during her pregnancy. While no records of Charles Edward's childhood memories exist, Alice fondly recalled this period. The nursery environment was typical for the late 19th century, characterized by early mornings, porridge, vigorous hair-brushings, buttoned boots, pinafores, pick-a-back rides, stories, squabbles, tears, treats, punishments, bland meals, walks to feed ducks, special covered baskets for sick children, pony rides, hot baths, firelight, lamplight, warming-pans, good-night prayers, and nightlights.

Although their care was mainly delegated to nannies, the children spent set periods with their mother daily. Helen taught them practical skills like knitting and gave them Sunday school lessons, reading to them from well-known English and Scottish authors. She was an affectionate yet strict mother, insisting on discipline and a sense of duty, though her son did not respond well, developing a fear of his mother and authority in general. Charles Edward, his mother, and sister were surrounded by the wider royal family, often visiting Queen Victoria at her estates. Charles Edward was reportedly Victoria's favorite grandchild. The children often visited Balmoral Castle, where they prepared for their future roles. Victoria enjoyed her grandchildren acting out dramatic scenes reflecting religious values. Lewis Carroll, a family friend, called Charles Edward a "perfect little prince," well-versed in court etiquette. Princess Helen also took her children on visits to her relatives in Germany and the Netherlands.

Public duties were part of royal functions, though they were somewhat naive about the harsh conditions of much of the British population. Charles Edward's mother, unusually for a German aristocrat, was particularly interested in social issues. According to Alice, the children were encouraged to sympathize with others and engage in charitable work. Charles Edward developed an early interest in military and royal occasions. As a child, he was given his first ceremonial position in the Seaforth Highlanders regiment of the British Army. Queen Victoria noted in her diary the five-year-old Prince wearing the "full uniform of the Seaforth Highlanders." Shortly before his 13th birthday, Charles Edward participated in a parade for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. He was observed climbing onto the roof of Buckingham Palace to view the crowds and was described in the contemporary press as the most well-received participant.

1.3. Education

Historian Hubertus Büschel noted that the British royal family held high expectations for their young members' education. Charles Edward's first teacher was a governess named "Mrs Potts," who taught him and his sister. From her lessons, where they reenacted historical scenes, the siblings developed a lifelong interest in history. Charles Edward was later sent to school without his sister, attending the privately funded public school system. He went to two prep schools: first Sandroyd School in Surrey (now in Wiltshire), and later Park Hill School in Lyndhurst. In 1896, Queen Victoria noted in her diary a meeting with Park Hill's headmaster, "Mr Rawnsley," finding his account "most satisfactory," describing him as "very careful & kind." In 1898, the prince enrolled at Eton College, a boarding school closely associated with the British elite, with his mother hoping he would proceed to Oxford University. While some press reports accused him of self-importance at Eton, he was happy there and looked back on his time nostalgically throughout his life. Aronson described the prince in his early teens as "small, blue-eyed, exceptionally handsome and highly strung." At this point, he was not expected to become a particularly prominent figure.

2. First Years in Germany

Charles Edward's life took a dramatic turn when he was unexpectedly selected as heir to the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, necessitating his move to Germany and a reorientation of his education and identity.

2.1. Selection as Heir

The death of Duke Alfred's only son, Prince Alfred, in 1899, coupled with the Duke's own poor health, brought the question of succession to the throne of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the forefront for the family. Many German governing elites viewed Duke Alfred as an inadequate foreigner, and some German princes desired to partition the duchy among themselves. Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert's third son, was initially the heir presumptive. However, segments of the German press opposed a foreigner on the throne, and Wilhelm II particularly objected to a man who had served in the British army ruling a German state. Wilhelm II demanded a German education for Arthur's son, Prince Arthur of Connaught, who was at Eton with Charles Edward. This condition was unacceptable to the Duke of Connaught, leading both he and his son to renounce their claims to the duchy. This left Charles Edward next in line. The young prince was named heir under considerable family pressure. American press reports even claimed that the younger Arthur had physically assaulted or threatened Charles Edward if he did not accept the position.

Charles Edward appeared unhappy with this imposed change. Historian Alan R. Rushton quoted him saying: "I've got to go and be a beastly German prince." Rushton suggested that adults around him encouraged him to embrace his new role. His sister recalled their mother saying, "I have always tried to bring up Charlie as a good Englishman, and now I have to turn him into a good German," though Büschel and Aronson interpreted this as an expression of his mother's frustration. At only fourteen years old, Charles Edward's youth, combined with his German mother and the absence of his British father, meant he was considered capable of assimilating into German society in a way an older man would not be. The local newspaper in Coburg praised the choice, and there was significant public interest in Germany regarding his future. Rushton noted that some Germans felt "it was now important for the English boy to become a German man and leader of his adopted land." Before his departure for Germany, the prince was Confirmation. Queen Victoria, in her diary, conveyed her sympathy: "Poor Helen & Charlie had borne up well during the service, but were much overcome afterwards. It is very hard upon the poor child having to be uprooted like this, & it is naturally a great wrench for him, & for his mother it is really terrible to have her whole future deranged to give up for the time being her happy quiet home & to give up her fatherless boy to go into the unknown!"

2.2. Education and Adaptation

Charles Edward, at fifteen years old, moved to Germany with his mother and sister, speaking little German. Duke Alfred intended to separate Charles Edward from his mother, so Helen took her son to stay with her brother-in-law, King William II of Württemberg, and found him a tutor. Helen then deliberated on his education, prioritizing reassurance to Germans that he was being raised in a proper German manner. Various extended family members offered suggestions. Alfred wanted to be responsible for his heir, but was deemed too British. A school proposed by Empress Victoria was, according to Alice, believed to have too many Jewish pupils. Ultimately, Helen granted Wilhelm II control over her son's education.

According to Urbach, Wilhelm aimed to transform his young cousin into a "Prussian officer." He invited the family to reside in Potsdam, a town near Berlin that served as the German emperor's summer residence. Charles Edward attended the Preußische HauptkadettenanstaltGerman (Prussian Central Cadet Institute) at Lichterfelde. Wilhelm informed Queen Victoria via telegraph that eight well-behaved boys had been chosen to form a class for Charles Edward. The prince studied the German language and military science. On his 16th birthday in 1900, he was made a lieutenant of cavalry and joined the 1. Garderegiment zu FußGerman (1st Foot Guards) at Potsdam. In 1903, Charles Edward completed his university entrance qualification, though his results were not publicly released. He then studied government management at various Prussian government ministries. He also attended Bonn University, studying law, but was not particularly academic, primarily enjoying his participation in the Corps Borussia Bonn.

Wilhelm II was so invested in Charles Edward's assimilation that the latter was known in the Imperial Court as "the Emperor's seventh son." The prince, along with his mother and sister, spent considerable leisure time at the German court in Berlin, treated as members of the emperor's family. Wilhelm's seven children, whose older members were close in age to the Albany siblings, became "like another brother and sister" to them, as Alice later wrote. While the women got along well with Empress Augusta Victoria, Wilhelm became a surrogate father figure for Charles Edward. Wilhelm perceived Charles Edward as impressionable, introducing him to his own worldview, which included antisemitism, German nationalism, and hostility towards the ReichstagGerman (parliament). During a political scandal in 1908, there were allegations of Charles Edward engaging in homosexual activity with Wilhelm. Despite this, Charles Edward often found his time in Berlin unpleasant, as the emperor seemed to become resentful and frequently bullied him. A 1905 diary entry by an official at the Berlin court commented: "The Emperor loves to have fun with him [Charles Edward]. But what usually happens is that he pinches and puffs him so much that the poor little Duke actually gets beaten up. Recently his bride, Princess Victoria and her parents were also present; This probably made it particularly embarrassing for the poor little Duke, who almost fought back tears and had such an unhappy expression on his face the whole evening, as if he were about to be hanged the next morning."

2.3. Regency

Charles Edward inherited the ducal throne of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at the age of sixteen upon the death of his uncle Alfred in July 1900. His tears at the funeral were interpreted by Urbach more as an expression of fear for his future than grief for an uncle with whom he had little relationship. Wilhelm II appointed Prince Ernst of Hohenlohe-Langenburg as regent until Charles Edward's 21st birthday. In 1901, Charles Edward attended Queen Victoria's funeral wearing the uniform of the Prussian Hussars. His eldest paternal uncle, Edward VII, who succeeded Queen Victoria, was seen embracing Charles Edward at the funeral. The new king appointed his nephew a Knight of the Garter in 1902. Charles Edward's mother decided he was old enough to manage himself in 1903 and left Germany with Alice. In May 1905, Edward VII appointed him Colonel-in-chief of the Seaforth Highlanders, a British army regiment.

Charles Edward diligently strove to assimilate into German society while maintaining some ties with Britain, such as participating in Anglican religious services. Urbach suggested he quickly mastered the German language, noting that his "German essays [at the military academy] were soon receiving higher marks than his English ones." However, his statements from this period often revealed his homesickness and unhappiness. Charlotte Zeepzat, author of his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), described him as a "conscientious young man with a taste for the arts and music," who became popular in Coburg during this time. Aronson similarly commented that despite growing up in an "atmosphere of strident Prussian militarism," he was "cultivated," "fond of music and the theatre," and "interested in history and architecture." Urbach, however, described the young duke as "immature." A contemporary news report noted his fondness for "sport and adventure." A 1905 article in the London and China Express, a British newspaper, observed: "All the [German] newspapers sing the praises of the young Duke and describe his sympathetic character and bearing. Above all they are never tired of emphasising how German he has become, how he has completely forgotten the English training of his early youth, identifying himself in every way with the interests of Germany."

3. Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

This period details Charles Edward's reign as Duke, his personal life, and his evolving loyalties during the lead-up to and during World War I, culminating in his deposition.

3.1. Marriage and Children

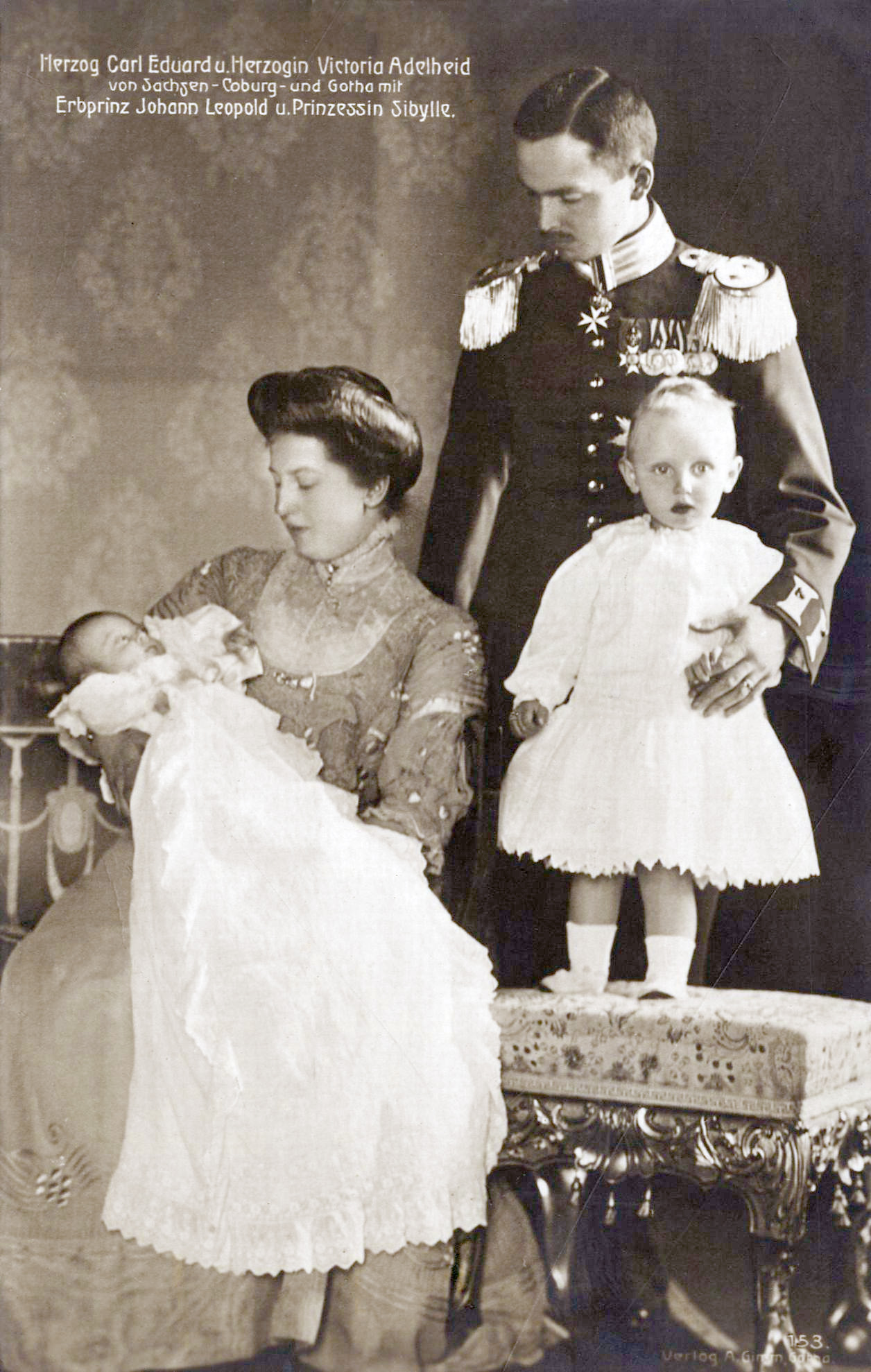

Given Charles Edward's "ambiguous" attitude towards women, according to Urbach, his family decided an arranged marriage at a young age was necessary. Wilhelm II chose his wife's niece, Princess Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein, as the bride. She was considered well-adjusted and loyal to Wilhelm's royal house. Her German nationality was deemed important, and she lacked any non-German or Jewish ancestry. Charles Edward was instructed to propose, which he did. A degree of affection existed between the young couple, though Urbach indicated their happiness was debatable in later years. They married on 11 October 1905, at Glücksburg Castle, Schleswig-Holstein, and had five children.

The couple's five children were: Prince Johann Leopold (1906-1972), Princess Sibylla (1908-1972), Prince Hubertus (1909-1943), Princess Caroline Mathilde (1912-1983), and Prince Friedrich Josias (1918-1998). Princess Sibylla later became the mother of King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden. As was typical for upper-class households of the era, the care of the children was largely delegated to domestic servants. The family primarily spoke English at home, although the children became fluent in German. Hubertus was the Duke's favorite child. A 1914 profile of the family in the British newspaper The Sphere described the children as "bright, happy children who lead a natural life, spending a great deal of their time in the open air in the fine grounds of their castle. They are very fond of riding. In the winter, which is a severe one in Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, they delight in ski-ing and other outdoor amusements suitable to snowy weather." In later years, Urbach noted that Charles Edward's children feared their father, who treated them "like a military unit," and often appeared unhappy in photographs. His younger daughter, Princess Caroline Mathilde, alleged that her father had sexually abused her, an accusation supported by one of her brothers. Charles Edward was often disappointed by his children's romantic choices, at a time when he was attempting to use strategic marriages to restore the diminished reputation of his royal house.

3.2. Peacetime Reign and Interests

Charles Edward assumed full constitutional powers upon reaching his majority on 19 July 1905. At his investiture, he delivered a speech pledging allegiance to the German Empire and was met with cheers after publicly sampling local food. He expressed contentment with his new territories, finding them beautiful. To emphasize his loyalties, he joined various patriotic groups. However, according to Urbach, the Duke lacked widespread popularity. This was particularly evident in Gotha, an impoverished town with left-wing sympathies, where he was perceived as absolutist. In Coburg-a wealthy, conservative, and intensely nationalistic town-residents were generally more sympathetic but disliked a perceived foreignness about him, as he retained an English accent. He also faced criticism for keeping Scottish Terrier dogs and for always appearing in public with a police guard.

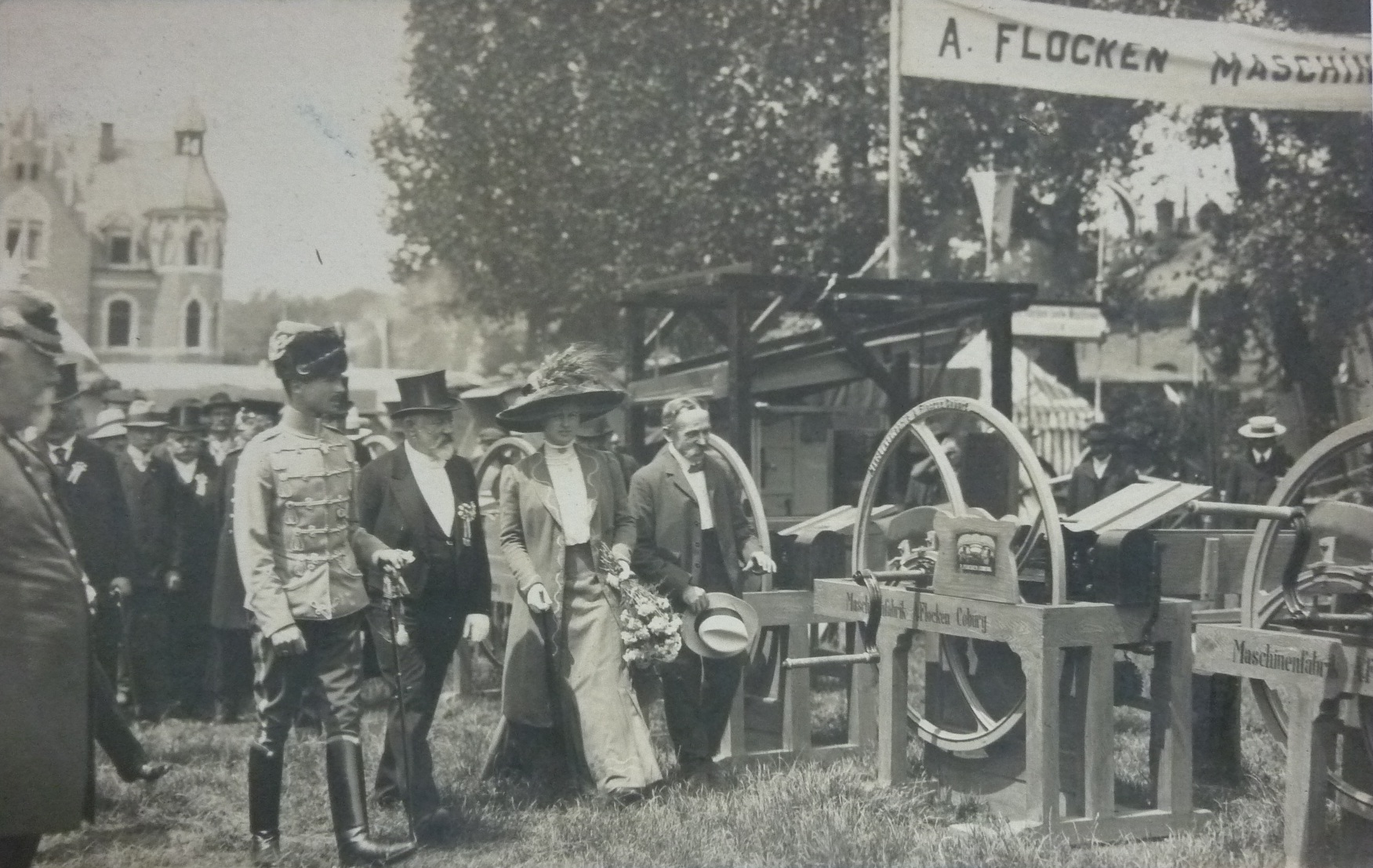

Historian Friedrich Facius initially described Charles Edward as a liberal who later shifted towards a more authoritarian stance. He was supportive of the emperor and understood governmental institutions. The new duke appointed Ernst von RichterGerman, a conservative-leaning, Prussian government official, as his prime minister. According to Rushton, the Duke's political worldview was "conservative and nationalistic," reflecting the influence of Wilhelm II. He largely delegated governance to his appointed cabinet, who adopted the motto "Everything as it has been" to describe their approach. Charles Edward frequently attended local events and was a prominent figure in local civic life, chairing and patronizing numerous cultural and charitable organizations.

The Duke displayed a keen interest in new forms of transportation, particularly automobiles and airships. He invested in constructing a new airship docking bay in Gotha, a decision that appeared commercially sound. In 1913, he secretly requested Wilhelm II to convert the civilian flying school in Gotha into a military one, a request the Kaiser granted. He enthusiastically supported the court theatres in both towns and oversaw the restoration of the Veste Coburg, which took place between 1908 and 1924. In 1910, he joined the "Reich Association against Social DemocracyGerman", a pro-monarchist political organization. Charles Edward was keenly concerned with public perception, with his officials actively surveying public opinion. The Duke frequently tried to emphasize his loyalty to Germany through displays of cultural traditions such as Christmas festivities and folk costumes.

He maintained a good relationship with the British royal family and regularly visited the United Kingdom. In 1910, the Daily Mirror published a photograph of him in the uniform of the Seaforth Highlanders during an inspection of its veterans. In private, he frequently engaged in British activities even while in Germany, such as performing Scottish country dances to bagpipes with the Duchess. His immediate family used English-language nicknames. Charles Edward received regular visits from his sister Alice and his brother-in-law Prince Alexander of Teck. He developed a close bond with Edward, Prince of Wales, during the latter's university years in the early 1910s. The Duke generally tried to remain aloof from politics, especially diplomatic issues between Great Britain and Germany. Büschel believed that Charles Edward's efforts to appear German during this period were likely attempts to appease Wilhelm II and German nationalists, rather than genuine expressions of his own identity.

Members of the German political elite were often irritated by the Duke's continued close relationship with Great Britain. Some of the sharpest criticism came from the lower-ranking nobility of Franconia, who viewed themselves as the purest of the German nobility. For instance, Baron Konstantin von GebsattelGerman asserted that "foreigners" holding German titles were a "nuisance" because they hindered a necessary battle against the "cancer" of Judaism, the SPD (a left-wing German political party), and "freedom." While the Imperial German government was less radical, it was displeased by some of Charles Edward's actions. His decision to wear the uniform of his ceremonial British regiment at the funeral of Edward VII in 1910 caused particular annoyance. Officials at the German Embassy in London were suspicious of his frequent visits to the United Kingdom.

The Duke became a major local landowner with an annual income of about 2.50 M DEM in 1910, which was equivalent to approximately 122.00 K GBP at the time. By 1918, his estimated wealth ranged between 50.00 M DEM and 60.00 M DEM. He divided his time, living in both Coburg and Gotha for several months each year, and also visited his mountain or hunting lodges. His routine typically involved working in the mornings and dedicating afternoons to leisure activities like hiking. Recreation consumed most of his time, and he frequently traveled abroad or within other parts of Germany. Charles Edward struggled with social interaction, particularly with those different from him. He restricted local people from entering the countryside surrounding his castles, further contributing to his seclusion. He tended to spend much of his time in the company of courtiers who regularly offered him praise. Historian Juliet Nicolson described these years as "the perfect summer," a period when privileged individuals enjoyed their wealth and social advantages, often in denial of emerging political and organised labour threats. Rushton commented on the Duke's personal situation during this period: "Charles Edward had every reason to be happy with his life: a growing healthy family, minimal professional duties, the opportunity to live very well and associate with his friends and relatives at the upper echelons of society in Europe... As 1914 began, Charles Edward had not the slightest clue that the golden age of the European nobles was coming to a climax. He continued to hunt and travel, acting as an absolute sovereign... His life as a monarch seemed to exist in a parallel world that had little in common with the majority of his subjects."

3.3. First World War and Relations with Britain

The outbreak of the First World War presented Charles Edward with a profound conflict of loyalties, yet he ultimately chose to support the German Empire. He was in England to receive an honorary degree as a Doctor of Civil Laws from Oxford University when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. He confided in his sister, Alice, that he wished to fight for Great Britain but felt obligated to return to his duchy, where public opinion increasingly turned against him due to his British origins. He returned to Germany on 9 July. After the war, he would describe the events of 1914 in a letter to his sister as the end of his personal "happiness."

At the war's onset, the German press criticized the foreign connections of the German aristocracy, with Charles Edward facing particular accusations of being a "half-Englishman." The Duke publicly denounced Britain, accusing it of attacking Germany, and renounced his position as Colonel-in-chief of the Seaforth Highlanders. He chose to sell his British military decorations rather than returning them, a gesture Büschel interpreted as a public display of contempt towards his family. He severed relations with his family at the British and Belgian courts, but this was insufficient to quell doubts about his loyalties within Germany. His attitudes would become more genuinely pro-German as the war progressed.

Charles Edward was unable to participate in combat as his leg had been permanently damaged in a sledging accident. Nevertheless, he provided non-combat support to the army corps from his territories, accompanying them into active war zones. He initially participated in the German invasion of Belgium, where he witnessed the Sack of Dinant by German soldiers, resulting in hundreds of Belgian civilian deaths. His adjutant Marcel von Schack, who believed the Belgian civilians were treated correctly, wrote that the event made an "unforgettable impression" on the Duke. In early September 1914, he was transferred to the Eastern Front. He expressed disdain for the living conditions of the local people he encountered on the Eastern Front, finding the homes of Jews, in particular, to be dirty. Charles Edward received an Iron Cross "for bravery" at the end of 1914. During the middle war years, he made various visits to the Western Front and areas of conflict in the Balkans.

The Duke never held a combat command. Soldiers from his duchies were awarded the Carl-Eduard-KriegskreuzGerman (Carl Eduard War Cross). His adjutant kept diaries documenting Charles Edward's activities, which were reported to German military command and circulated in the German press for propaganda purposes. These reports depicted him as sharing in the soldiers' difficult living conditions and celebrating Christmas with them. In reality, he suffered from rheumatism and ankylosing spondylitis, a type of arthritis, and generally remained far behind the frontlines, regularly returning to Germany for medical treatment. This earned disapproval from some within the German elite who felt a young soldier should suppress his illnesses. According to Urbach, Charles Edward "was more or less a chocolate soldier, who spent most of his time dining at various casinos behind the front and visiting 'his' Coburg troops."

The Duke also acted as an intermediary between the German government and his relative Ferdinand I, ruler of the Kingdom of Bulgaria, a member of the Central Powers. Ferdinand had declared Bulgarian independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1908, and the Kingdom had faced economic crisis after the Second Balkan War. Charles Edward had provided significant assistance, including financial support, during these events. In 1916, when Ferdinand wished to go to war with the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with Germany, Charles Edward traveled to the Bulgarian capital of Sofia on Wilhelm's behalf and successfully persuaded Ferdinand against it.

In Britain, the Duke was widely denounced as a traitor. He was one of several noblemen residing in Germany and Austria who held British titles but sided with the Central Powers, frequently labeled as "traitor peers" in the British press. For instance, shortly after the war, The Sunday Post published a report on "traitor dukes," including a vitriolic profile of Charles Edward's life, calling his role in the war "one of the blackest chapters in his ignominious career." Büschel noted that describing the Duke as a traitor was accurate, as he remained a British subject and participated in a war against the United Kingdom, never having formally become a German national.

In 1915, King George V ordered his name removed from the register of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. In 1917, a legal change in Coburg effectively barred Charles Edward's British relatives from succeeding to the duchy. This decision was praised by German newspapers, with one declaring he had "torn" his relationship with his birth country. Over the summer of 1917, bombers built in Gotha, named after the town, conducted multiple air raids in London and South East England, killing several hundred British civilians. That year, Charles Edward's British property, worth several million pounds, was confiscated. In response, he introduced a legal change to prevent his British relatives from ever inheriting his other property. The British royal family later changed its name from the German-sounding Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the House of Windsor. The Titles Deprivation Act 1917 initiated the process of stripping him of his British titles. Urbach observed that Charles Edward appeared indifferent to the possibility that his actions might endanger his mother, who was living in London under the protection of Queen Mary.

Charles Edward worked for the military staff on the Western Front during the later war years. He contributed 250.00 K DEM from his personal wealth as financial support for the families of fallen soldiers from his territories. A report published in The Times a few years after the war commented that he had often assisted British prisoners of war, describing this as a sign of his "consideration and humanity." The Duke was alarmed by the murder of the Russian royal family in 1918, as Empress Alexandra was one of his first cousins. He feared his own family might suffer a similar fate. Rushton noted this as the beginning of his fear of communism, which would define his political activities in the coming years. He joined the PreußenbundGerman (League of the Emperor's Loyalists), an organization of supporters of the German emperor, though he personally favored German general and de facto military dictator Paul von Hindenburg as a leader. Büschel argued that Charles Edward's First World War experiences served as a "school for nationalism, violence, and antisemitism."

3.4. Deposition and Abolition of Monarchy

The war imposed severe burdens on the German population, and after mid-1918, the empire's military situation collapsed. By late in the year, an armistice was signed and a revolution broke out in Germany. On 11 November 1918, a peaceful demonstration against the Duke occurred in Coburg. The duchy's prime minister, Hermann QuarckGerman, convinced the local SPD, which had many relatively well-off members, that further unrest would jeopardize the town's character. The political climate in Gotha, where people were starving, was more radical, and the Workers' and Soldiers' Council effectively seized control.

Charles Edward responded more slowly than most other ruling princes to the escalating situation. He announced that he had "ceased to rule" on 14 November but did not explicitly abdicate. According to Rushton, the delay in Charles Edward's abdication stemmed from his anxiety that he would be killed. However, the transition of power in Coburg was relatively calm and orderly compared to transfers in other parts of Germany. While the German nobility was not physically attacked during the revolution, the situation was deeply frightening to them and became a significant source of resentment.

4. Post-World War I and the Weimar Republic

In the aftermath of World War I, Charles Edward navigated a period of significant personal and political change, ultimately embracing far-right ideologies.

4.1. Loss of British Titles and Property

After the war, Urbach noted that Charles Edward remained unpopular in Germany and was still regarded by some as English. By the war's end, the left-wing, anti-royalist press had begun nicknaming him "Mr Albany," highlighting his foreign origins. Despite this, he was able to live relatively contentedly in Coburg. According to Rushton, he largely retained his prestige, and his former subjects often viewed him as still essentially their duke. Coburg was a politically conservative town, and the new post-war world was unsettling for many. Its inhabitants continued to look to Charles Edward for guidance. Shortly after the war, Coburg became part of the German state of Bavaria, while Gotha became part of Thuringia. While Bavaria's conservative political culture suited Coburg well, this administrative change marked a significant cultural shift, reinforcing the perception that the former duke and his family remained the natural leaders of the community.

In 1919, he also formally lost his British titles. Despite this, some personal sympathy for him persisted among the political establishment in the United Kingdom, largely owing to the circumstances under which he had been compelled to move to Germany as a teenager. He continued to use some of the iconography and titles associated with the British royal family for the rest of his life. He visited his mother and sister in London in 1921 but was generally unwelcome in Britain. When Charles Edward's mother died in 1922, the British government prevented him from inheriting Claremont House, a development that greatly displeased him.

In 1919, his properties and collections in Coburg were transferred to the Coburger LandesstiftungGerman (Coburg State Foundation), which still exists today. A similar resolution for Gotha took longer, and only after legal disputes with the Free State of Thuringia was it established between 1928 and 1934. After 1919, the family retained Callenberg Castle, some other properties (including those in Austria), and the right to reside at Veste Coburg. They also received substantial financial compensation for lost possessions. The refurbishment of Veste Coburg was completed at the state's expense. Some additional real estate in Thuringia was restored to the ducal family in 1925. Despite the post-war democratic German state posing little threat to his property, Charles Edward remained paranoid about a communist revolution. In a 1928 letter to his sister, he wrote: "I only hope our winter will remain quiet but the Russians seem to be getting our communists on the move... In different parts of Germany they have begun attacking our nationalists, but have luckily been beaten off with cracked crowns. If only the leaders would leave the workmen in peace. They are so sensible, 'wenn sie nicht verhetzt werdenGerman' (when they are not riled up)."

4.2. Far-Right Politics and Support for the Nazi Party

In the post-First World War period, Charles Edward continued to describe himself as a monarchist. It was said he aspired to return to political power as "King of Thuringia." In practice, however, his enthusiasm for monarchical restoration was rather lukewarm. His emotional attachment to the German emperor largely dissipated with Wilhelm's exile. The former duke began seeking political alternatives that he perceived as stronger than the deposed German emperor.

Charles Edward became far more overtly involved in politics after his deposition, actively supporting the nationalist and conservative right. The former duke harbored nostalgia for aspects of pre-war Germany, especially its militarism, and was greatly frightened by communism. Urbach also suggested he had an obsession with masculine physical strength, stemming from his perceived lack of it. He became associated with various right-wing paramilitary and political organizations. Rushton noted that he "became a member and patron of the paramilitary group Coburg EinwohnerwehrGerman, the Bund WikingGerman and the veterans group Der StahlhelmGerman." The Bund Wiking had previously been the Organisation Consul in the early 1920s, a group he also funded and participated in. This organization was involved in the politically motivated murders of politicians Karl GareisGerman and Walther Rathenau. Urbach critically commented that, "Though Carl Eduard did not himself murder, he financed murderers." Police reports from the time noted that he and Victoria Adelaide attended public speeches that expressed support for far-right terrorism.

Charles Edward also provided funding to various antisemitic nationalist groups. In 1922, he was invited to a traditional event where the top-performing student from a local gymnasium (academically focused German secondary school) would deliver a speech. That year, the student was a Jewish young man named Hans Morgenthau. The former duke demonstratively expressed his disapproval by turning his back on Morgenthau and holding his nose throughout the speech. On 14 October 1922, the Nazi Party participated in a nationalist event called the Deutscher TagGerman (German Day) in Coburg, which involved significant violence. That evening, Charles Edward attended a meal organized by the party where Adolf Hitler spoke. The next day, he shook hands with Hitler, making him the first nobleman to publicly support the future dictator. Police investigated whether the former duke had encouraged his oldest son, Leopold, to join the Young German Order, an antisemitic paramilitary organization. In the autumn of 1923, press reports indicated that Leopold had led a series of attacks on Jewish people around Coburg, with particular attention given to incidents in the village of Autenhausen where Jewish farmers were seriously injured. It was alleged that the former duke had bribed witnesses to protect his son from prosecution.

In 1920, Charles Edward provided refuge for Hermann Ehrhardt, a Freikorps commander and later leader of the Organisation Consul, in one of his castles, along with a cache of weapons, after Ehrhardt participated in the unsuccessful Kapp Putsch against the government. Büschel suggested that Ehrhardt, who was dissatisfied with Wilhelm II and his heir, Crown Prince Wilhelm, may have harbored ambitions of making Charles Edward the monarch of all Germany. In 1923, the value of the German mark collapsed. Both the radical left and right wings of politics saw this as an opportunity to change the system of government. Communists attempted to instigate a revolution in Thuringia and Saxony. Ehrhart and 5,000 followers, including Charles Edward's eldest son, responded by preparing to march into Thuringia. The federal German government then suppressed the left-wing state governments in those areas, re-establishing its authority from the perspective of public opinion. While Charles Edward was irritated by the unsuccessful Beer Hall Putsch by the Nazi Party a short time later-because it disrupted Ehrhart's own attempts to seize power (the leader of Bavaria, Gustav von Kahr, had been planning a coup with Ehrhart before Hitler initiated a coup against him)-the former duke did hide Nazis in one of his castles afterward.

From 1929 onward, Charles Edward provided financial support to the Nazi Party. In 1932, Callenberg Castle was renovated, with a Swastika added to a tower. The former duke was attracted by the party's militarism and anti-communism. Hitler had also expressed opposition to the expropriation of royal property. Charles Edward proved a valuable ally for the Nazis during their rise to power, possessing extensive connections in Franconia and across Germany.

In 1929, his support contributed to Coburg becoming the first town in Germany to elect a Nazi Party council. This election had stemmed from a dispute involving a Nazi supporter who was dismissed from his job for attacking Jews. Charles Edward's attendance at Nazi Party events was covered in the local press, significantly increasing the party's profile and prestige. Following the Nazi Party's local election victory in 1929, politically motivated violence against their opponents became common and was tolerated by the local police. The Jewish population of Coburg also experienced increasing physical abuse and discrimination. Rushton asserted that the former duke's publicly expressed beliefs and financial support contributed to the growth of hatred towards Jewish people in Coburg and Germany as a whole. It was widely known that Charles Edward and his wife were antisemitic. According to Rushton, Charles Edward would have been aware of the violent behavior of the movements he was involved in but never objected, as his experiences in the First World War had convinced him of the merits of political violence.

The former duke and Waldemar Pabst established the "Society for Studying Fascism" in 1931. This organization aimed to design a plan for governing Germany based on the example of Italian fascism. Mussolini's dictatorship appealed to Charles Edward and others like him, who saw fascism as a method of governing that could integrate the traditional aristocracy with a new elite. In 1932, the former duke was elected leader of the National KlubGerman, a social club whose membership was largely composed of businessmen disaffected with the post-war system of government. He encouraged them to join the Nazi Party, and by the end of the year, 70% had done so. Also in 1932, he participated in the creation of the Harzburg Front, which brought the German National People's Party and other like-minded groups into association with the Nazi Party. He also publicly urged voters to support Hitler in the presidential election of 1932. While the Nazi Party lost that election nationwide, they secured a victory in Coburg.

In 1932, Charles Edward's daughter Sibylla married Prince Gustaf Adolf, Duke of Västerbotten, the eldest son of the Crown Prince of Sweden and second-in-line to the Swedish throne. This marriage positioned Sibylla to potentially become Queen of Sweden, though this ultimately did not occur. Charles Edward used the event as a public display of his ideology and to enhance the damaged prestige of his royal house. More than a decade after the First World War, it offered an opportunity for his family to regain prominence in international royal circles. Coburg was decorated with Swedish and Nazi flags, and 5,000 men in Nazi uniforms marched outside Veste Coburg. Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring extended their congratulations for the marriage.

King George V prevented Edward, Prince of Wales, from attending the wedding due to objections to Charles Edward's political views, although some of Charles Edward's British relatives did attend. In Sweden, which was experiencing political instability with a growing republican movement, the wedding became quite controversial due to the symbolism used and Gustaf's known Nazi sympathies. The Swedish government was promised certain changes to the event's program, but these were not fulfilled. The wedding received extensive coverage in both the German and foreign press.

5. Activities under the Nazi Regime

Charles Edward's deep and active involvement with the Nazi Party and its associated organizations marked a dark chapter of his life, showcasing his roles within the regime and his complicity in its policies.

5.1. Joining the Nazi Party and Key Positions

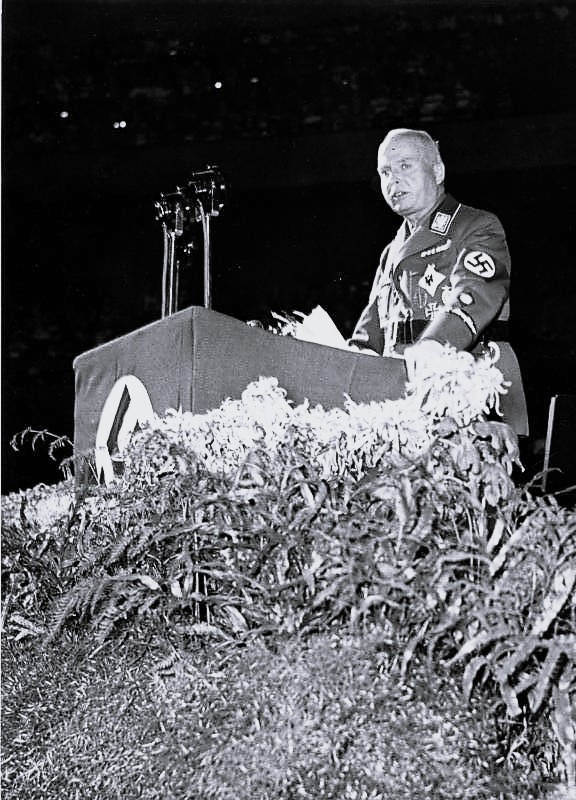

In 1933, the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. Charles Edward promptly began flying the Nazi flag over Veste Coburg. He formally joined the Nazi Party in March 1933 and was also appointed an ObergruppenführerGerman (Senior Group Leader) in the SturmabteilungGerman (SA, or Storm Division). Meanwhile, a temporary prison was established in the center of Coburg, where Jewish people and opponents of the regime were tortured, with no effort made to conceal these actions. The former duke was swiftly granted various ceremonial titles and held positions on the boards of multiple businesses. A photo collection of senior figures in the new regime, published by a German private company, ranked him at number 43. In 1934, Charles Edward publicly declared his unwavering loyalty, stating he would "blindly follow Hitler forever."

According to Urbach, the former duke became a "highly honoured" member of the party, frequently appearing in photographs with its senior figures and establishing an office in Berlin to cultivate relationships. She noted his pride in his Nazi Party membership, believing that the SA uniform allowed him to feel more like his pre-war self. He lost the right to use his SA uniform after the Night of the Long Knives, a decision that greatly upset him, yet he accepted the politically motivated murders. He was later granted a Wehrmacht general's uniform. Some figures within the Nazi Party harbored suspicions of the former duke, believing he was motivated by ambition or sought to restore the monarchy. He awarded his own personal medal to several Nazi supporters until the regime halted this practice in 1936.

Charles Edward was made president of the National Socialist Automobile Association, an organization that supplied vehicles to the German state, including those used in the implementation of the Holocaust. From 1936 to 1945, he served as a member of the ReichstagGerman (Nazi Germany), representing the Nazi Party. In his appointment diaries, which he kept from 1932 to 1940, he frequently expressed enthusiastic support for the party. For instance, he meticulously recorded the results of the 1936 one-party election and lauded the outcome. Büschel commented that by this stage in his life, the former duke appeared to fully regard himself as German. Büschel also described Charles Edward's luxurious lifestyle during this period: "...[The] importance that Carl Eduard had for the Hitler regime was evident in the luxury of apartments befitting his rank and the amenities of a large fleet of vehicles, diligent adjutants, administrators and servants as well as abundant foreign currency... Carl Eduard lived more unmolested under National Socialism than in the Weimar Republic at the Coburg Castle and his numerous other castles. The dispute over properties in Thuringia and Austria, which had been confiscated by the state authorities after the end of the First World War, was soon resolved in favour of the ducal family, not least through the intervention of high-ranking National Socialist party members."

5.2. President of the German Red Cross

On 1 December 1933, Charles Edward was appointed head of the Deutsches Rotes KreuzGerman (German Red Cross). Hitler approved the appointment due to his familiarity with the former duke and his belief that Charles Edward supported Nazi ideas relating to race and eugenics. The appointment also aligned with a historical tradition of aristocrats participating in humanitarian activities. His connections to European royalty made him a useful figurehead for the organization abroad. He was expected to share power with the German Red Cross's deputy leader, Dr Paul Hocheisen. A power struggle ensued between the two men during the early months of Charles Edward's presidency as he attempted to assert his authority. In the summer of 1934, the party largely transferred control over the German Red Cross to Hocheisen.

The organization was swiftly compelled to conform with the government's goals. Rushton commented that, "Two years after the founding of the new regime, the DRK [German Red Cross] was remodelled into a paramilitary organization with the goal of providing support for soldiers in a time of conflict." The treatment of political prisoners in Germany-opponents of the Nazis who had been imprisoned after they came to power-became a subject of international scrutiny in the early years of the regime. After the Swedish Red Cross requested an investigation into the matter in 1934, the International Red Cross began making inquiries. The German Red Cross asserted that conditions for the prisoners were better than their usual quality of life. Charles Edward facilitated a tightly controlled tour of the concentration camps, including Dachau, for his friend, the President of the International Red Cross, Carl Jacob Burckhardt, in 1935. Burckhardt privately found the camps "brutal," but his heavily censored report stated that conditions were adequate. Burckhardt later wrote to the former duke, thanking him for organizing the tour.

In 1937, Ernst-Robert Grawitz was appointed deputy leader to strengthen the organization's ties with the SS. Charles Edward was designated "an officer of the chancellery of the Fuhrer," granting him access to private government information. Senior roles within the German Red Cross were increasingly filled by Nazi Party members, and members of the organization were indoctrinated with the belief that "the Jews, Slavs, chronically ill, handicapped... were nothing more than worthless." Charles Edward's public prominence within Germany gradually diminished during the regime's early years, and he almost entirely ceased making domestic public appearances after Grawitz's appointment in 1937. The regime was becoming increasingly radical and viewed the former duke as a symbol of the past.

5.3. Eugenics and Nazi Ideology

Eugenics-the fringe theory that a human population can be "improved" over generations by encouraging certain people to have children and discouraging others-originated in the 19th century and gained increasing popularity among German academic circles in the decades leading up to the Nazis' rise to power. In the early 20th century, children from poorer families often exhibited poorer health and a higher likelihood of developing behaviors deemed destructive compared to their wealthier counterparts. This implicitly led some to believe that social class differences might be genetic. Anxieties regarding the genetic health of the German nation were exacerbated by the First World War, during which large numbers of able-bodied men were killed or crippled, while those deemed incapable of combat remained at home.

Growing scientific research into eugenics occurred in subsequent years, and Hitler himself endorsed the idea during the 1920s. The Great Depression intensified concerns that disabled people were a drain on public resources, prompting scientists and even non-Nazi politicians to increasingly discuss the concept of voluntary sterilization for these groups. The Nazi Party expressed strong support for eugenics in the early 1930s. Internationally, eugenic ideas received wide support across the political spectrum in the early twentieth century, and eugenic policies, such as compulsory sterilization of "defectives," were implemented in several countries. However, the theory lost mainstream support after World War II due to its use by the Nazis to justify mass murder.

Charles Edward served on the governing body of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute from 1933 to 1945, and as secretary of its executive board from 1934 to 1937. In these roles, he was involved in promoting eugenicist ideas to the German public, particularly among influential individuals. The Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring introduced mandatory sterilization for certain groups deemed an undesirable burden on the German nation. The German government later organized multiple schemes to murder disabled people during the regime's reign. The first scheme, targeting children, ran from 1939 until the end of the war, resulting in the deaths of 5,300 disabled children. The second scheme, known as Aktion T4, operated from late 1939 to mid-1941, killing over 70,000 disabled individuals at six killing centers in Germany and Austria, primarily through gassing; Grawitz was heavily involved in this. In August 1941, this scheme was halted, as it was perceived to be distressing the German populace and undermining wartime morale. A third scheme in the later years of the war employed more covert methods, largely deliberate starvation, and is estimated to have killed between 100,000 and 180,000 people.

Most evidence clarifying the German Red Cross's level of involvement in these events was destroyed, either accidentally or deliberately, by the end of the war. While much of the victim transportation was handled by a proxy organization created for that purpose, the German Red Cross was involved in transporting some victims. Many of the nurses engaged in murdering disabled people were employees of the German Red Cross who had been indoctrinated by the organization. Rushton believed that Charles Edward would have been aware of these schemes, given his extensive media consumption and social connections; contemporary regime evidence and later studies suggest such knowledge was common among the German population. Princess Maria Karoline, a member of the former duke's extended family, was murdered by the program in 1941, despite upper-class disabled people generally receiving some protection through private healthcare and family political connections. According to Rushton, Charles Edward did not intervene because "he had not been concerned that anything would happen to her." He received a letter of condolence claiming her death was due to natural causes, which he did not believe. Uncharacteristically for a man who rarely missed family events, he did not attend her funeral.

5.4. Unofficial Diplomat

The Nazi regime extensively utilized Charles Edward as an informal diplomat. While the German Red Cross was essentially under regime control, it was presented to foreign audiences as an independent humanitarian organization. The former duke held little power over its domestic governance but served as a significant international figurehead. Charles Edward embarked on his first worldwide tour on behalf of the new German government in 1934.

He visited Japan, where he attended a conference on the protection of civilians during wartime and delivered Hitler's birthday greeting to Emperor Hirohito. This conference allowed Charles Edward to be seen by a global audience as a humanitarian figure, enhancing the regime's international reputation. Hitler was interested in an alliance with the Japanese government, and Charles Edward used the visit to foster connections with the Japanese imperial family. In a report he wrote for Hitler about the tour, the former duke frequently expressed prejudiced views and complained about perceived Jewish influence in the United States.

Charles Edward was particularly instrumental in Nazi attempts to cultivate pro-German sentiments among the British aristocracy. Urbach noted Charles Edward's "endless reconnaissance trips [to Britain] in the 1930s." He aimed to help the German government establish an alliance with the British and personally desired the return of Claremont House. Urbach wrote that Charles Edward reintegrated himself into aristocratic social life in Britain, aided by his sister Alice, and associated with prominent aristocrats and politicians. These included Neville Chamberlain, who became British prime minister in 1937, and members of the British royal family, especially Edward, Prince of Wales, who held strongly pro-German views. The former duke served as president of the Deutsch-Englische GesellschaftGerman (German-English Society) and lobbied Britons believed to be pro-German. He was appointed head of the organization after the regime deemed it insufficiently pro-Nazi. He attended George V's funeral in a German military uniform and helmet. He also visited veterans' meetings in the United Kingdom. Duff Cooper, the British Secretary of State for War, described a party organized on Charles Edward's behalf at Alice's country home in 1936: "The point of it was to meet the Duke of Coburg, her brother. It was a gloomy little party-so like a German bourgeois household... I was tactfully left alone with the Duke of Coburg after luncheon in order that he might explain to me the present situation in Germany and assure me of Hitler's pacific intentions. In the middle of our conversation his Duchess [Victoria Adelaide] reappeared carrying some hideous samples of ribbon in order to consult him as to how the wreath that they were sending to the funeral [of George V's] should be tied. He dismissed her with a volley of muttered German curses and was afterwards unable to pick up the thread of his argument."

Zeepvat contended that Charles Edward's advocacy had little success and that he failed to grasp the extent to which the people he had grown up around now perceived him as a foreigner. In contrast, Urbach argued in her 2015 book that the stresses experienced by British society during the interwar period had a radicalizing effect on sections of the British elite, and that significant sympathy for fascism-though with discomfort regarding Nazism specifically-existed among the aristocracy. She suggested that Charles Edward may have exerted some influence on instances of appeasement of Germany in the 1930s, such as the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, British acceptance of the German remilitarisation of the Rhineland, and the Munich Agreement.

Charles Edward hosted an international press tour associated with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor's visit to Germany in 1937. He also hosted Edward and Wallis Simpson themselves during their visit. He visited Italy in 1938, meeting King Victor Emmanuel III and dictator Benito Mussolini. He undertook a trip to Poland, where he met Polish officials six months before the country was invaded by Germany and the Soviet Union.

In 1940, Charles Edward traveled through Moscow and Japan to the US, where he met President Roosevelt at the White House. He claimed that the German Red Cross was protecting the welfare of the recently conquered Polish people. The American Red Cross was quite hostile to the visit, and while there was some criticism in US newspapers, he was generally well received in the US press. In a private report, the German embassy in Washington claimed that the Duke's personal appeal had prevented the visit from resulting in a diplomatic failure for the Germans. The former duke signed an agreement with the American Red Cross allowing them to send humanitarian aid to Poland, though much of this was ultimately confiscated by the SS. In Japan, he worked to improve relations between the German and Japanese governments after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had caused a dispute between them. He visited Japanese-occupied Manchukuo, touring hospitals and similar institutions with journalists. Büschel suggested this was likely an attempt by Japanese authorities to convince world opinion that people in Manchukuo were receiving adequate humanitarian assistance from their new rulers.

5.5. World War II Activities

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Charles Edward once again found himself on the opposite side of a war from his birth country; there is no evidence that this caused him any distress or led him to doubt his political convictions. Although the former duke was too old for active service, his three sons served in the Wehrmacht. In 1941, he began keeping a diary to record war news, using different colored pens for different sources of information. When his son, Hubertus, died in an air crash in 1943, Charles Edward noted in his diary: "Hubertus † fürs VaterlandGerman" (Hubertus died for the Fatherland), underlining the shorthand cross for death in the color he used for Wehrmacht reports. In 1942, Charles Edward was asked by his relative Prince Eugene of Sweden to arrange for Martha Liebermann, an elderly Jewish woman, to be granted permission to emigrate to the United States. He took no action to help, and Liebermann later took her own life after being ordered to report for deportation to Theresienstadt Ghetto.

Charles Edward's support for Nazism intensified during the war years and never wavered. Hitler reportedly considered making him King of Norway after the war. The former duke likely ceased acting as an informal diplomat after 1940. His health was declining, and he appeared older than his years. He continued to wear uniforms and traveled to countries that were either occupied by Germany, members of the Axis powers, or neutral. A 1941 edition of Les Actualités mondialesFrench, a newsreel circulated in German-occupied France, showed him visiting the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and undertaking German Red Cross activities in France. Traveling abroad was a privilege afforded to very few German civilians during the war years. It remains unclear what Charles Edward's specific political activities were during this period, but he received 4.00 K DEM monthly from the German government, drawn from a fund Hitler had established for useful associates. In 1940, Charles Edward helped mediate a diplomatic dispute between the British and German governments regarding the treatment of prisoners of war, preventing a number of prisoners on both sides from being shackled. In 1943, at Hitler's behest, Charles Edward asked the International Red Cross to investigate the Katyn massacre.

In April 1945, codebreakers at Bletchley Park deciphered an order from Hitler stating that Charles Edward should not be allowed to be captured, which Urbach interpreted as Hitler wanting him killed. That same month, Charles Edward agreed to the surrender of Veste Coburg to US forces. He also assisted them in extinguishing a fire in the castle museum that had been started by the bombardment. He was on the US Army's list of suspected war criminals and was placed under house arrest until his transfer to a prisoner of war camp in November. During his questioning, he reportedly drank wine with his captors in one of the castle's sitting rooms. His interrogators found him ignorant, obnoxious, and possibly mentally unstable. In an interview, he stated he would accept an offer to participate in a new German government, made a series of demands, and claimed that "no German is guilty of any war crimes." These comments were considered so useful for Allied propaganda that they were used in a radio broadcast in April 1945. He also expressed the view that it had been right to remove Jews from public life and that Germans were inherently unsuited to democracy.

6. Post-War Period and Death

Following World War II, Charles Edward faced internment, trial, and a life marked by diminished circumstances and the consequences of his Nazi affiliations.

6.1. Trial and Denazification

After the end of the Second World War, Charles Edward was interned by the American military authorities from 1945 to 1946. His sister, Princess Alice, lobbied for his release on health grounds. Following his release, he and Victoria Adelaide moved into a cottage outside Callenberg Castle, as the castle itself was being used as a home for refugees. Alice visited the couple in 1948, recounting their impoverished state and her brother's severe illness with arthritis. She successfully persuaded the authorities to allow them to move into a part of one of his residences, closer to where his sister-in-law could procure food.

In April 1946, Charles Edward's daughter Sibylla gave birth to a son, Carl Gustaf, who at birth was third in the line of succession to the Swedish throne. In January 1947, Sibylla's husband died in a plane crash, and in October 1950, Gustaf V of Sweden died, at which point Charles Edward's grandson became Crown Prince of Sweden, later ascending to the throne as King Carl XVI Gustaf.

Charles Edward's trial, part of the denazification process, spanned four years and included two appeals. Alice and many other associates dishonestly spoke on his behalf, downplaying his involvement in the Nazi regime. Approximately a year after the war, the priority of the Western Allies shifted from punishing former Nazis towards preparing their occupation zones to become part of the Western Bloc during the Cold War. In 1950 (or August 1949, according to his ODNB entry), the former duke was classified by a denazification court as a MitläuferGerman and MinderbelasteterGerman (roughly: 'follower' and 'follower of lesser guilt'). His biographer Carl Sandner critically called the result a "farce." Charles Edward also lost significant property due to his participation in the Second World War. His property in Gotha, situated in the Soviet occupation zone, was confiscated and redistributed by the Soviet forces.

He spent the last years of his life in relative seclusion and poverty, impacted by the substantial fines imposed by the denazification tribunal and the seizure of much of his property by the Soviets. However, his lifestyle largely returned to normal after his trial. In 1953, he was transported by ambulance and wheelchair to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom at a cinema in Coburg. He was reportedly close to tears while watching his relatives, including his sister. According to a column published that year in The Scotsman, the former duke had reestablished links with the Seaforth Highlanders, a British Army regiment of which he had once been colonel-in-chief, and which was then stationed in Germany. The column noted that an invitation to a regimental ball was sent to the Duke, with a note from the Commanding Officer (Lieutenant-Colonel P. J. Johnston) expressing the battalion's wish for their old Colonel-in-Chief to be present despite the distance. The Duke replied, stating that although his health prevented him from attending, he was deeply touched by the invitation, "renewing old connections which existed between the Seaforth Highlanders and myself for so many years, and which I honestly hope and wish will not be severed again." He offered to receive any comrade passing through Coburg as a guest and signed himself "Charles Edward. Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Duke of Albany."

6.2. Death

Charles Edward died of cancer in his flat in Coburg on 6 March 1954, at the age of 69. He had reportedly told his son Friedrich Josias that Queen Victoria had always wanted him to be a "good German." His obituary in The Times commented that "...he was Hitler's man... Whether, and to what extent, he was admitted to the inner council of the Nazi gang is as yet an open question." Representatives of various royal houses across Europe sent condolences, but the British royal family offered no comment.

Charles Edward's funeral was held on 10 March and presided over by a Lutheran dean who had served as a church official under the Nazi regime. The dean described Charles Edward as a good man who had been manipulated by others and mistreated by the Allies. The former duke's death was officially mourned in Coburg. A civil servant who refused to fly a flag at half-mast for his funeral was reported to the district council in Bayreuth and condemned by a member of the Parliament of Bavaria. Victoria Adelaide received many letters of support in the weeks following her husband's death, including from former senior Nazis. Charles Edward's burial took place on 12 October, observed by a crowd of well-wishers. He is buried at the Waldfriedhof Cemetery (Waldfriedhof BeiersdorfGerman) near Callenberg Castle, in the Beiersdorf district of Coburg.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

Charles Edward's controversial life continues to be critically assessed, particularly concerning his affiliations with the Nazi regime and their enduring social impact.

7.1. Family and Contemporary Perceptions

His sister's autobiography, For My Grandchildren (1966), discusses Charles Edward's life. In it, she portrayed her brother as a victim of prejudice during the First World War and suggested he remained in Germany primarily due to family obligations. She minimized his role in the Nazi regime. Urbach argued that the autobiography is intentionally misleading and selective. In his 1981 biography of Alice, Aronson noted that some members of the British royal family believed Charles Edward supported the regime "due to his conviction that Hitler had saved Germany from Communism." Aronson also recorded Alice's account of her brother's harsh imprisonment after the war-"he found conditions almost unbearable... Many of his fellow prisoners died there..."-but also her acknowledgement that "No doubt, their jailers had seen some of the ghastly German concentration camps and were determined to treat these old officers with the utmost severity."

Rudolf Preisner, an amateur historian from Coburg, wrote the first biography of Charles Edward's life in 1977. The former duke's son, Friedrich Josias, wrote a letter to Preisner criticizing the book. Among other errors, he felt that the book was overly sympathetic to his father, whom he believed was aware of the Holocaust. He stated that his brother, Hubertus, had witnessed deportations of Jewish people to extermination camps and frequently discussed the subject with the family. Friedrich Josias himself had planned to write a biography about his father but never did so.

7.2. Modern Re-evaluation and Criticism

In December 2007, Britain's Channel 4 aired an hour-long documentary titled Hitler's Favourite Royal about Charles Edward. A review in The Guardian described the film as "A solid documentary on a feeble man and a wretched family." Another review in The Daily Telegraph suggested the documentary had been overly sympathetic to Charles Edward, stating that the "story emerged as a tale of pure tragedy. Which it undoubtedly was, in parts," but that he was depicted "as if the trauma of being elevated to a dukedom and losing it had somehow robbed him of his ability to tell right from wrong."

Urbach noted that there was some disagreement among the production team of the 2007 documentary on whether Charles Edward should be portrayed as a man struggling with politics in a foreign country or as an ideological Nazi, leading to a contradictory depiction of his character. She stated that new evidence recovered between 2007 and 2015 demonstrated that he was "obviously not a naive victim of circumstances but a very active supporter of Hitler." Urbach argued that Charles Edward shared a similar character to Hitler, commenting that the two men shared "ideologies and of course their narcissistic personalities (the only creatures they both declared a fondness for were their dogs)." She also described his life as "an example of thorough re-education... away from the constitutional monarchy he was reared in to dictatorship." Urbach's 2015 book Go Betweens for Hitler discusses how various aristocrats, including Charles Edward, acted as informal diplomats for Nazi Germany. A review in The Times commented on Charles Edward that: "For many years thereafter [the German Revolution], Carl Eduard was regarded as a mere footnote in history; a harmless, potty old aristocrat, washed up by the seismic upheavals of the early 20th century. However, that benign interpretation has been recently revised. We now know that Carl Eduard was a member of the Nazi Party, a sponsor of paramilitary terrorism and-as Urbach's excellent book demonstrates-an important 'go-between' for Hitler."

7.3. Social Impact and Controversies

Büschel suggested in his 2016 biography of Charles Edward that the various pressures placed on the nobleman from childhood until the outcome of the First World War may have contributed to him developing split personality disorder and narcissism. The writer posited that the Nazi regime allowed the former duke to regain much of the status he had lost after the First World War. He commented that Charles Edward was influenced by "coercion, fear, indoctrination, the effort to 'stay on top,' and probably also inner homelessness and loneliness." Büschel suggested that this was similar to the experiences of many of the Duke's German contemporaries. However, Büschel also believed that Charles Edward freely chose to support the Nazi regime, despite the option of leaving Germany being relatively easy for him. He characterized the former duke as the most active and enthusiastic of the regime's aristocratic supporters, describing him as a "second-tier perpetrator": someone who was not a central figure in the regime but who helped to conceal policies that would lead to the deaths of millions of people.

Rushton, in his 2018 book about the former duke's relationship to the murder of disabled people, described Charles Edward's life as "the story of a man born to royalty who became ensnared in the politics of human destruction. It is a tragic story." Rushton suggested there would have been risks to Charles Edward and his family if he had chosen to object to any actions of the regime, citing examples of other former nobles who were persecuted. Rushton noted that Charles Edward had already lost his status as a British prince and German duke, making his new identity as a Nazi party leader deeply emotionally important to him. Rushton argued that the factors affecting Charles Edward's behavior were similar to those affecting many Germans. However, the historian also pointed out that the former duke had a close friendship with Hitler and argued that he could have encouraged Hitler to halt certain atrocities. The writer felt that Charles Edward's failure to respond to the murder of a member of his extended family indicated that he was "weak-willed." Rushton contended that this "...reflects a moral character defect... low self-esteem and little self-respect... [lack of action is often due to] fear of others' opinions in the community and the risk to one's comfortable and secure lifestyle."

In 2015, a local dispute occurred in Coburg regarding whether a street should be named after Max Brose, a businessman with links to the Nazi regime. In response, the Coburg town council commissioned a group of historians to investigate why support for the Nazis developed unusually quickly in Coburg and events in the town during that period. The commission, which reported its findings in 2024, noted that Charles Edward was an influential figure in the town, and that his support for VölkischGerman organizations significantly contributed to the growth of far-right politics.