1. Early Life and Education

Charles Bell's early life in Edinburgh laid the groundwork for his multifaceted career, influenced by his family's intellectual environment and his early exposure to both medicine and art.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Charles Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 12 November 1774, as the fourth son of the Reverend William Bell, a clergyman of the Scottish Episcopal Church. His father passed away in 1779 when Charles was only five years old, leading his mother to play a significant role in his early education, teaching him to read and write. Bell grew up in a family of accomplished brothers who also greatly influenced his professional path. His elder brothers included Robert Bell (1757-1816), a Writer to the Signet; John Bell (1763-1820), who became a renowned surgeon and writer; and George Joseph Bell (1770-1843), an advocate who later served as a professor of law at the University of Edinburgh and a principal clerk at the Court of Session. Charles's decision to pursue a medical career was significantly inspired by his brother John.

1.2. Education and Artistic Training

Bell attended the prestigious High School, Edinburgh from 1784 to 1788. Although he was not considered an outstanding student, his inclination towards medicine became clear. In 1792, he enrolled at the University of Edinburgh, commencing his medical studies by assisting his brother John as a surgical apprentice. During his time at the university, Bell engaged with subjects beyond medicine, notably attending lectures on spiritual philosophy by Dugald Stewart, which would later influence his philosophical writings, such as a passage in his Treatise on the Hand. Alongside his anatomy classes, Bell deliberately pursued courses in drawing, refining his inherent artistic talent. His artistic abilities were further honed through regular drawing and painting lessons paid for by his mother, under the tutelage of David Allan, a distinguished Scottish painter. This artistic training proved invaluable throughout his career, profoundly shaping his approach to anatomical illustration and the study of human expression. As a student, he was also an active member of the Royal Medical Society, even speaking at its centenary celebrations in 1837.

After graduating from the University of Edinburgh in 1798, Bell was admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. He began teaching anatomy and performing surgical operations at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. During this period, his interests began to converge, combining anatomy with art. His artistic skills were evident when he contributed significantly to his brother John's four-volume work, The Anatomy of the Human Body, writing and illustrating volumes 3 and 4, published in 1803. He also released his own illustrations in A System of Dissections in 1798 and 1799. Bell further developed a unique hobby of creating wax models of interesting medical cases, leveraging his clinical experience and artistic eye. This collection, which he named his Museum of Anatomy, grew substantially, with some pieces still housed today at Surgeons' Hall in Edinburgh.

2. Professional Career

Charles Bell's professional journey took him from Edinburgh to London, where he achieved significant recognition as a surgeon and teacher, before his eventual return to his native Scotland.

2.1. Edinburgh Period and Early Challenges

Bell's initial period in Edinburgh as a practicing surgeon and teacher was marked by professional rivalries and institutional barriers. A notable feud between his brother John Bell and two prominent faculty members at the University of Edinburgh, Alexander Monro secundus and John Gregory, significantly impacted Charles's career. John Gregory, as chairman of the Royal Infirmary, had limited the number of full-time surgical staff, and neither of the Bell brothers was selected, effectively barring them from practicing at the Royal Infirmary. Despite not being directly involved in his brother's disputes, Charles Bell attempted to negotiate with the university faculty, offering 100 GBP and his Museum of Anatomy in exchange for the opportunity to observe and sketch operations at the Royal Infirmary, but his offer was rejected. These professional obstacles ultimately prompted his departure from Edinburgh.

2.2. Move to London and Teaching

In 1804, Bell decided to move to London, where he swiftly established himself. By 1805, he had acquired a house on Leicester Street, transforming it into a teaching space. From this location, Bell began conducting classes in anatomy and surgery, attracting a diverse group of students, including medical students, practicing doctors, and artists. His ability to synthesize complex anatomical knowledge with clear artistic representation quickly garnered him a reputation as an influential teacher.

2.3. Military Service and Surgical Experiences

Bell's commitment to medicine extended beyond the classroom, leading him to volunteer his surgical skills during wartime. In 1809, he was among the civilian surgeons who journeyed to Corunna, Spain, to attend to the thousands of sick and wounded soldiers who had retreated there. Six years later, in 1815, he again volunteered his services in the aftermath of the devastating Battle of Waterloo. For three consecutive days and nights, Bell tirelessly operated on French soldiers at the Gens d'Armerie Hospital in Brussels. The conditions of the soldiers were dire, and despite his efforts, many of his patients succumbed to their injuries. Out of 12 amputation cases he performed, only one soldier survived.

Bell was particularly fascinated by musket-ball injuries, and in 1814, he published a detailed Dissertation on Gunshot Wounds. Many of his vivid illustrations of these wounds are still exhibited today in the hall of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. While serving in military hospitals, he also meticulously recorded neurological injuries at the Royal Hospital Haslar. Despite his dedication, his surgical skills were critically viewed by some, including Dr. Robert Knox, one of his surgical assistants at Brussels, who noted the high mortality rate of Bell's amputation cases, approximately 90%.

2.4. Academic Appointments and Institutional Contributions

Bell's career progressed through a series of prestigious academic and institutional appointments. In 1811, he married Marion Shaw, and using her dowry, he purchased a share of the Great Windmill Street School of Anatomy, which had been founded by the celebrated anatomist William Hunter. Bell moved his practice from his home to the Windmill Street School, where he taught students and conducted his own research until 1824. Between 1813 and 1814, he was appointed as a member of the London College of Surgeons and also took on the role of a surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital.

Bell played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Middlesex Hospital Medical School. In 1824, his contributions were recognized when he was appointed the first professor of Anatomy and Surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons of England in London. In the same year, he sold his extensive collection of over 3,000 wax anatomical preparations to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh for 3.00 K GBP.

In 1829, the Windmill Street School of Anatomy was integrated into the newly formed King's College London. Bell was invited to serve as its first professor of physiology. He was instrumental in establishing the Medical School at the University of London, delivering its inaugural address and contributing to the requirements of its certification program. However, his tenure at the Medical School was short-lived, as he resigned due to differing opinions with the academic staff. For the subsequent seven years, Bell continued to deliver clinical lectures at the Middlesex Hospital. In 1835, following the premature death of Professor John William Turner, Bell accepted the prestigious position of Chair of Surgery at the University of Edinburgh, marking his return to his native city.

3. Scientific and Medical Contributions

Bell's profound scientific and medical contributions fundamentally reshaped the understanding of the human nervous system, anatomy, and physiology.

3.1. Discovery of Sensory and Motor Nerves

One of Bell's most significant contributions was his pioneering research distinguishing the functions of sensory nerves and motor nerves in the spinal cord. He published his seminal ideas in a privately circulated book in 1811, titled An Idea of a New Anatomy of the Brain. In this work, Bell theorized about different nervous tracts connecting to various parts of the brain, leading to distinct functionalities. His experimental approach involved carefully incising the spinal cord of a rabbit and touching different columns of the cord. He observed that irritating the anterior (ventral) columns resulted in muscle convulsions, while irritating the posterior (dorsal) columns produced no visible effect. Based on these observations, Bell asserted that he was the first to differentiate between sensory and motor nerves.

While his essay is now considered a foundational text in clinical neurology, it initially received a lukewarm reception from his contemporaries. His experimental methods were scrutinized, and his hypothesis that the anterior and posterior roots were connected to the cerebrum and cerebellum, respectively, was rejected. Furthermore, later analysis suggested that Bell's original 1811 essay did not contain as clear a distinction of motor and sensory nerve roots as he later claimed, with subsequent revisions appearing to have subtle textual alterations and incorrect dates. Despite the initial skepticism, the concept of separate sensory and motor nerve pathways was independently confirmed by the French physiologist François Magendie in 1822. This led to the formulation of the Bell-Magendie law, which states that the anterior spinal nerve roots contain only motor fibers, while the posterior roots contain only sensory fibers, a fundamental principle that revolutionized the understanding of the nervous system.

3.2. Research on the Nervous System and Bell's Palsy

Bell continued his in-depth studies of the human brain and its associated nerves. In 1821, he published his most celebrated discovery in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, in a paper titled On the Nerves: Giving an Account of some Experiments on Their Structure and Functions, Which Lead to a New Arrangement of the System. This paper detailed his crucial finding that the facial nerve, or seventh cranial nerve, is primarily responsible for muscular action in the face. This discovery had immediate clinical significance: at the time, surgeons often cut this nerve as a supposed cure for facial neuralgia, unknowingly causing unilateral paralysis of the facial muscles. This condition is now universally known as Bell's palsy, an idiopathic paralysis of facial muscles due to a lesion of the facial nerve. Bell's work on the facial nerve and his clinical description of Bell's palsy solidified his reputation as one of the first physicians to effectively bridge the scientific study of neuroanatomy with practical clinical application.

3.3. Anatomy of Expression and its Influence

Bell's artistic inclinations deeply influenced his scientific inquiry, leading him to investigate the intricate relationship between facial muscles and human expression. In 1806, with an aspiration for a teaching position at the Royal Academy, he published his influential work, Essays on The Anatomy of Expression in Painting, which was later re-published in 1824 as Essays on The Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression. In this treatise, Bell delved into the detailed anatomy of facial muscles, explaining how their contractions create the wide range of human emotional expressions. He applied principles of natural theology, asserting that the uniquely human system of facial muscles served to demonstrate humanity's special relationship with the Creator, echoing the ideals of William Paley.

Although his application to the Royal Academy was unsuccessful - Thomas Lawrence, who later became its President, reportedly described Bell as "lacking in temper, modesty and judgement" - his work on expression had a profound impact beyond the art world. His studies on emotional expression played a catalytic role in the development of Charles Darwin's considerations of the origins of human emotional life. While Darwin, in his The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), rejected Bell's theological arguments, he largely agreed with Bell's emphasis on the expressive role of the muscles involved in respiration. Darwin's work, written with the active collaboration of psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne, built upon Bell's foundational insights into human emotion and its physiological underpinnings.

3.4. The Bridgewater Treatise: "The Hand"

In 1829, Francis Egerton, the eighth Earl of Bridgewater, bequeathed a substantial sum of money to the President of the Royal Society of London. His will stipulated that the funds were to be used to commission, print, and publish one thousand copies of a work dedicated to demonstrating the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God as evidenced in the natural world. Davies Gilbert, then President of the Royal Society, appointed eight distinguished gentlemen to author separate treatises on this subject.

In 1833, Charles Bell contributed the fourth of these Bridgewater Treatises, a comprehensive work titled The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments as Evincing Design. Bell published four editions of this influential book. The initial chapters of the treatise are structured as an early textbook of comparative anatomy, featuring numerous illustrations where Bell compares the "hands" of various organisms, ranging from human hands to chimpanzee paws and even fish feelers. As the book progresses, Bell shifts his focus to the profound significance of the hand and its critical role in the field of anatomy and surgery. He passionately argued that the hand, akin to the eye, is an indispensable tool in surgery and must therefore be meticulously trained. This work synthesized his anatomical observations with theological contemplation, reflecting his broader philosophical worldview.

4. Artistic Works

Beyond his scientific prowess, Charles Bell possessed remarkable artistic talent, which he seamlessly integrated into his medical and anatomical pursuits, elevating the visual representation of medical knowledge.

4.1. Anatomical Illustrations and Publications

Bell was a highly prolific author, unique in his ability to combine profound anatomical knowledge with a keen artistic eye to produce numerous meticulously detailed and beautifully illustrated books. His first major artistic-anatomical work, A System of Dissections, explaining the Anatomy of the Human Body, the manner of displaying Parts and their Varieties in Disease, was published in 1799. He also played a crucial role in completing his brother John's four-volume set, The Anatomy of the Human Body, contributing significantly to volumes 3 and 4 in 1803.

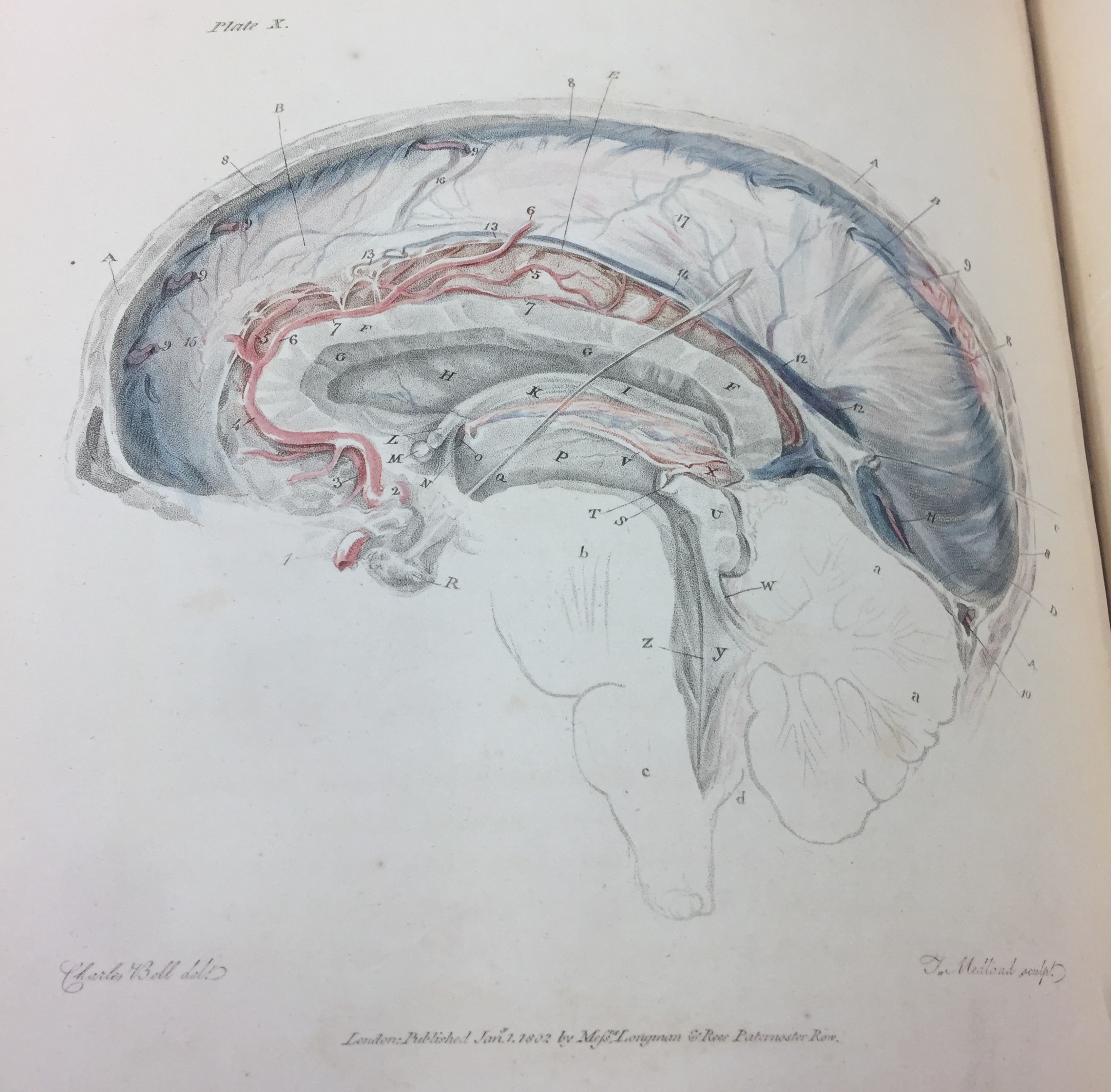

In the same year, Bell released three distinct series of engravings: Engravings of the Arteries, Engravings of the Brain, and Engravings of the Nerves. These sets comprised intricate and detailed anatomical diagrams, each accompanied by precise labels and concise descriptions of their functions within the human body. They were primarily conceived as essential educational tools for aspiring medical students. The Engravings of the Brain holds particular significance, as it marked Bell's first published attempt to comprehensively elucidate the complex organization of the nervous system. In its introduction, Bell candidly commented on the enigmatic nature of the brain and its internal mechanisms, a subject that would continue to fascinate him throughout his life.

4.2. Paintings and Sketches

Bell's artistic skills extended to painting and sketching, allowing him to capture not only anatomical structures but also the visual manifestations of human conditions and emotions. His early works for artists involved expressing anatomical descriptions through paintings. He notably authored the first treatise on the anatomy and physiology of facial expression specifically for painters and illustrators, titled Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting (1806).

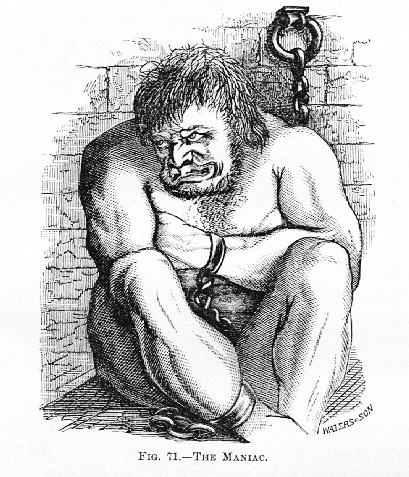

Among his most notable artistic pieces are the evocative painting

The Maniac (1806), which vividly portrays a disturbed individual, and

Opisthotonus (1809), depicting a patient suffering from tetanus with characteristic body arching. These works demonstrate his exceptional ability to render human form and medical conditions with both scientific accuracy and artistic sensitivity. He further utilized his artistic talent in publications such as his book Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery: Trepan, Hernia, Amputation, Aneurism, and Lithotomy (1821), which featured detailed surgical illustrations.

5. Ideology and Philosophy

Charles Bell's scientific pursuits were deeply interwoven with his philosophical and theological convictions, particularly his engagement with natural theology.

5.1. Natural Theology and Scientific Inquiry

Bell's intellectual framework was significantly shaped by his adherence to the principles of natural theology, a philosophical belief that attributes the order, complexity, and design observed in the natural world to a divine creator. This perspective profoundly informed his scientific inquiries. In his works, such as Essays on The Anatomy of Expression in Painting and The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments as Evincing Design (a Bridgewater Treatise), Bell explicitly argued for the existence of a uniquely human system of facial muscles and the intricate design of the hand as evidence of a benevolent and intelligent Creator.

He believed that the meticulous study of anatomy and physiology could reveal the wisdom and goodness of God manifested in creation. This view paralleled the ideas of contemporary natural theologians like William Paley. Bell's scientific observations, therefore, were not merely empirical but were also framed within a larger philosophical context that sought to understand the natural world as a testament to divine design. While his theological arguments were later challenged by scientific developments, particularly Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, Bell's commitment to natural theology provided a powerful motivation for his detailed anatomical investigations and his efforts to bridge the gap between scientific discovery and spiritual contemplation.

6. Honours and Awards

Sir Charles Bell received numerous distinguished recognitions and accolades throughout his illustrious career, acknowledging his significant contributions to science and medicine.

6.1. Fellowships and Royal Society Recognition

Bell was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh on 8 June 1807, based on nominations from prominent figures such as Robert Jameson, William Wright, and Thomas Macknight. He further contributed to the society by serving as a Councillor from 1836 to 1839. His scientific eminence was further cemented when he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London on 16 November 1826. In 1829, the Royal Society of London honored him with its prestigious gold medal, in recognition of his numerous groundbreaking discoveries in science. Additionally, Bell was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, placing him among an elite group of international scholars.

6.2. Knighthood

In recognition of his distinguished service and profound achievements in science and medicine, Charles Bell was knighted. He was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order in 1831 and again in 1833. This conferral of knighthood underscored the immense impact of his work and his respected standing within the British scientific and medical communities.

7. Personal Life

Beyond his demanding professional endeavors, Charles Bell maintained a personal life, which included his marriage.

7.1. Marriage and Family

Charles Bell married Marion Shaw in 1811. While the source material provides limited details about his family life, his marriage to Marion was a significant event that coincided with a pivotal period in his career, as her dowry enabled him to purchase a share in the Great Windmill Street School of Anatomy, furthering his professional independence and research opportunities.

8. Death

Sir Charles Bell's life concluded during a journey, bringing an end to a remarkable career dedicated to advancing medical knowledge and understanding.

8.1. Final Years and Passing

In his final years, Bell had returned to his native Edinburgh, accepting a professorship at the university. On 28 April 1842, while traveling from Edinburgh to London, Sir Charles Bell passed away at Hallow Park, near Worcester in the Midlands. He was laid to rest in the churchyard of Hallow, Worcestershire, near Worcester. His death came six years after his return to the University of Edinburgh.

9. Legacy and Influence

Sir Charles Bell's enduring legacy is evident in the fundamental shifts his work brought about in medicine, particularly in neurology and anatomy, and his contributions continue to be recognized through eponyms and institutions.

9.1. Discoveries and Medical Eponyms

Bell's pioneering research led to several medical terms and conditions being named in his honor, underscoring the lasting impact of his discoveries:

- Bell's (external respiratory) nerve: This refers to the long thoracic nerve, which innervates the serratus anterior muscle, responsible for protracting the scapula.

- Bell's palsy: This is an idiopathic (of unknown cause) paralysis affecting one side of the face, resulting from a lesion of the facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve). Bell's detailed clinical description of this condition was crucial for its understanding.

- Bell's phenomenon: A normal defense mechanism of the human eye, this describes the upward and outward movement of the eyeball that naturally occurs when an individual forcefully closes their eyes. Clinically, it can be observed in patients with paralysis of the orbicularis oculi muscle (e.g., in conditions like Guillain-Barré syndrome or Bell's palsy), as the eyelid remains elevated while the patient attempts to close the eye.

- Bell's spasm: This term refers to the involuntary twitching of the facial muscles.

- Bell-Magendie law (or Bell's Law): This fundamental law in neuroscience states that the anterior (ventral) branch of spinal nerve roots contains only motor fibers, which transmit signals from the brain and spinal cord to muscles, while the posterior (dorsal) roots contain only sensory fibers, which carry sensory information from the body to the spinal cord and brain. This discovery was pivotal in understanding the functional organization of the nervous system.

9.2. Impact on Later Scientific and Medical Thought

Bell's neurological research and anatomical studies had an enduring influence on the development of modern medicine. His differentiation of sensory and motor nerves provided a foundational understanding of nerve function, paving the way for advancements in clinical neurology and surgery. He is celebrated as one of the first physicians to successfully integrate the scientific study of neuroanatomy with practical clinical application, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and patient care. His detailed anatomical illustrations also set new standards for medical education and visual representation of the human body. Furthermore, his work on the anatomy of expression catalyzed Charles Darwin's groundbreaking theories on the origins and functions of human emotion, demonstrating Bell's impact across diverse scientific fields.

9.3. Memorials and Institutions

As a tribute to his significant contributions, institutions and structures have been named in his honor. One notable example is Charles Bell House, part of University College London. This facility is actively used for teaching and research in surgery, serving as a continuous reminder of Sir Charles Bell's profound and lasting influence on medical science.