1. Overview

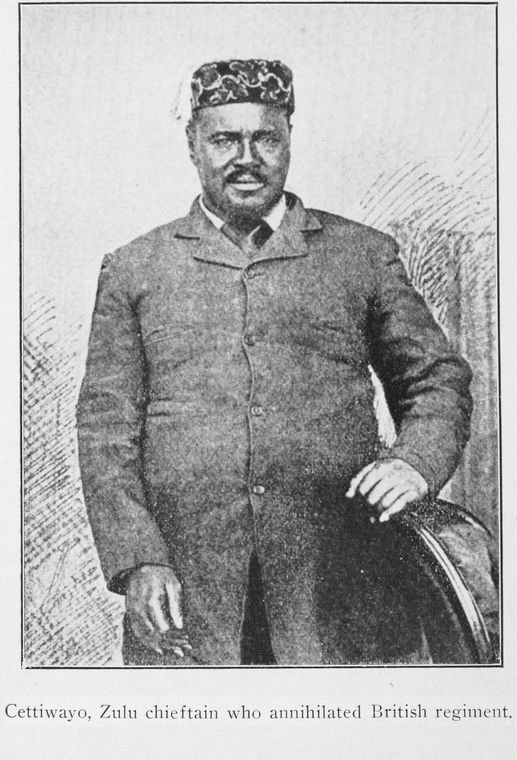

Cetshwayo kaMpande (Cetshwayo kaMpandekǀétʃwajo kámpandeZulu; circa 1826 - February 8, 1884), also transliterated as Cetawayo, Cetewayo, Cetywajo, and Ketchwayo, was the last sovereign king of the independent Zulu Kingdom, reigning from 1872 to 1879. He commanded the Zulu forces during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, where his army achieved a significant victory over the British at the Battle of Isandlwana, a rare instance of an African force defeating a Western imperial army. Despite his consistent efforts to make peace, he was ultimately defeated and exiled by the British. After a period of imprisonment in Cape Town and London, he was allowed to return to Zululand in 1883, but died shortly thereafter amidst escalating internal conflicts. His reign and resistance efforts are central to the history of Southern Africa and its struggle against colonial expansion.

2. Early Life

Cetshwayo's early life was marked by his royal lineage and a fierce struggle for succession against his half-brothers, which ultimately consolidated his power before he formally ascended the throne.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

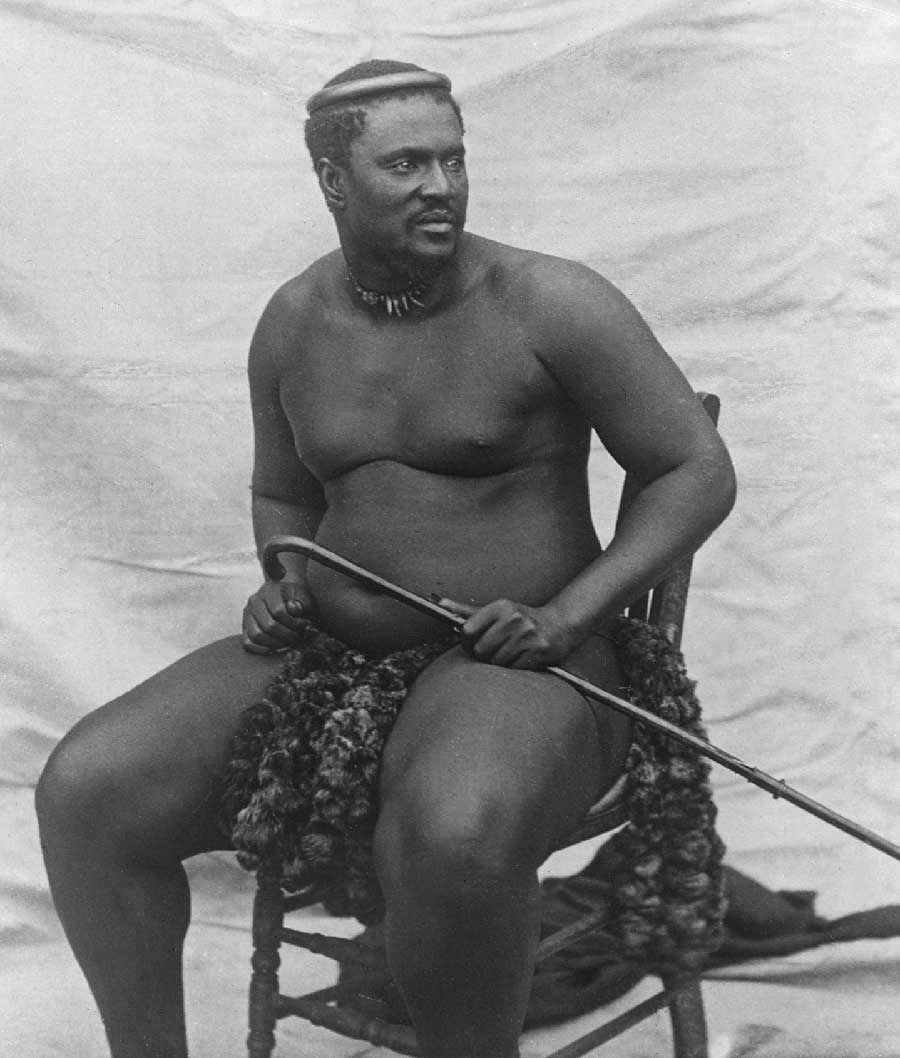

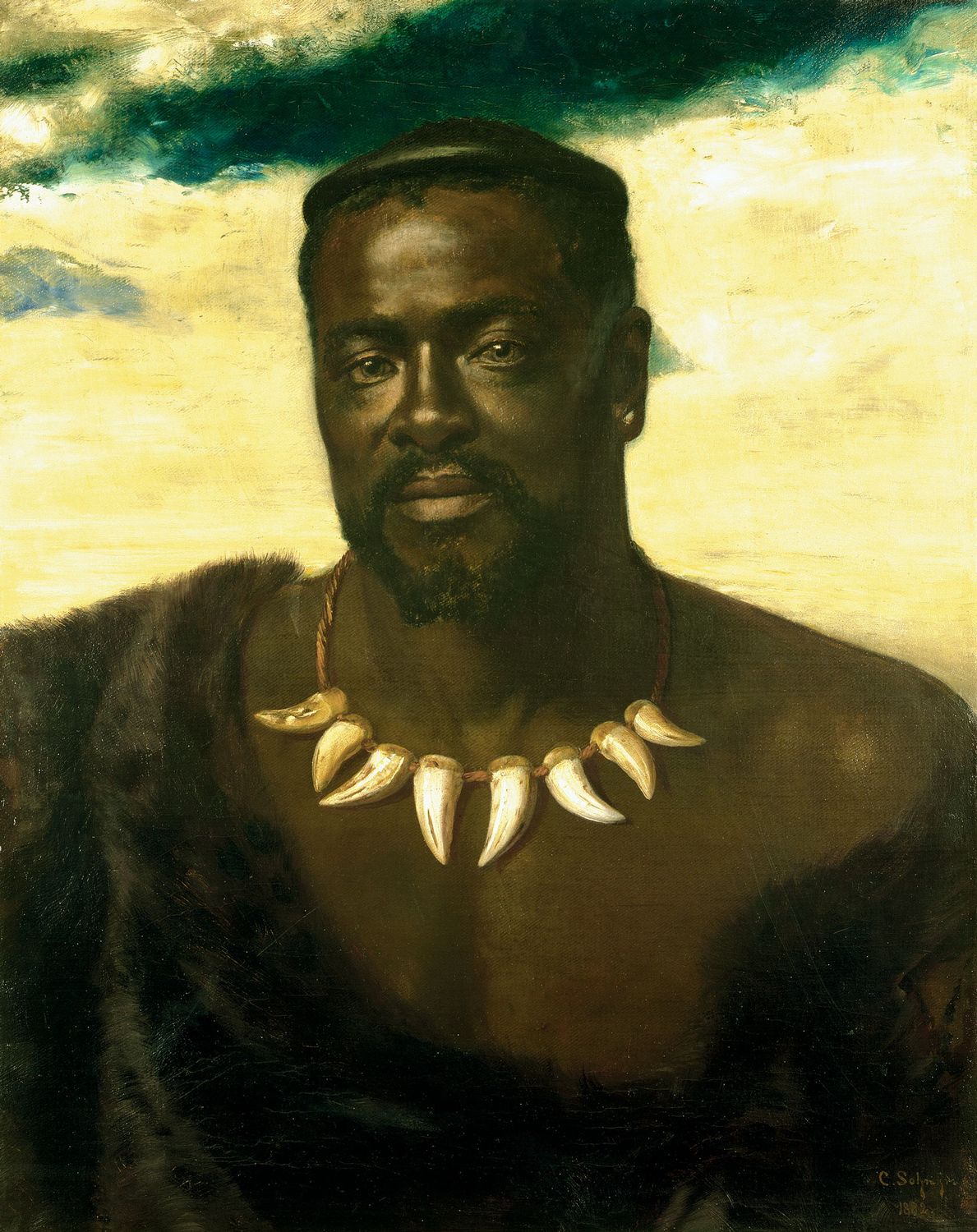

Cetshwayo was born around 1826, the eldest son of Mpande, who was then a leading figure in the Zulu Kingdom and later became its third king. His mother was Queen Ngqumbazi. Through his father, Cetshwayo was the half-nephew of the legendary Zulu king Shaka and a grandson of Senzangakhona, establishing his direct claim to the Zulu throne. He was noted for his imposing physical presence, reportedly standing between 6 in and 6 in tall and weighing close to 25 st.

2.2. Struggle for Succession

Cetshwayo's path to power was fraught with conflict. In 1856, he decisively defeated and killed his younger half-brother, Mbuyazi, who was his father Mpande's favored successor, at the Battle of Ndondakusuka. This battle was notoriously brutal, with almost all of Mbuyazi's followers massacred in its aftermath, including five of Cetshwayo's own brothers. Following this victory, Cetshwayo effectively became the de facto ruler of the Zulu people, even though his father Mpande was still alive.

His claim was not without continued challenges. Another half-brother, Umthonga, remained a potential rival. Cetshwayo also took extreme measures to eliminate potential threats from his father's new wives and children, notably ordering the death of Mpande's favorite wife, Nomantshali, and her children in 1861. Though two sons managed to escape, the youngest was reportedly murdered in front of the king. Umthonga subsequently fled to the Boer territories across the border, forcing Cetshwayo to engage in negotiations with the Boers for his return. In 1865, Umthonga again fled, leading Cetshwayo to suspect that Umthonga might seek Boer assistance against him, mirroring how his father Mpande had overthrown his predecessor, Dingane. Cetshwayo also faced opposition from his half-brother, uHamu kaNzibe, who notably betrayed the Zulu cause on multiple occasions.

3. Reign

Cetshwayo's reign marked a period of significant military build-up and a complex diplomatic dance with the encroaching British colonial powers, ultimately leading to war.

3.1. Ascension and Coronation

King Mpande died in 1872, though his death was initially kept secret to ensure a smooth transition of power. Cetshwayo was formally installed as king on September 1, 1873. His coronation was notably presided over by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, a British official who later annexed the Transvaal Colony to the Cape Colony. However, Shepstone's relationship with Cetshwayo deteriorated, particularly after Cetshwayo's skillful negotiations regarding land disputes undermined Shepstone's influence. A Boundary Commission, established to resolve the land ownership in question, even ruled in favor of the Zulus, a report that Shepstone reportedly suppressed.

After his coronation, in accordance with Zulu custom, Cetshwayo established a new capital for the nation, naming it Ulundi, meaning "the high place."

3.2. Zulu Kingdom's Military and Administration

As king, Cetshwayo embarked on a comprehensive program to strengthen the Zulu army, which he considered crucial for the kingdom's defense against external threats. He reintroduced and expanded upon many of the military methods and reforms originally established by his great-uncle, Shaka. He also took steps to modernize his forces, equipping his impis (Zulu regiments) with muskets, though their actual use in battle was limited.

In his administration, Cetshwayo sought to assert Zulu sovereignty. He took the significant step of banishing European missionaries from his land, viewing their presence as disruptive. There is also evidence to suggest he may have encouraged other native African peoples to rebel against the Boers in the South African Republic (Transvaal), further indicating his intent to resist foreign encroachment.

3.3. Relations with British Colonial Authorities

The period leading up to the Anglo-Zulu War was characterized by escalating tensions between Cetshwayo's kingdom and the British colonial authorities. Sir Henry Bartle Frere, the British High Commissioner for the Cape Colony, pursued a policy of confederating the South African colonies, inspired by the Confederation of Canada. He perceived the powerful Zulu state bordering the colony as an obstacle to this ambition.

Frere began to issue demands for reparations for alleged Zulu border infractions and instructed his subordinates to send messages complaining about Cetshwayo's policies, explicitly aiming to provoke the Zulu king. Cetshwayo, despite these provocations, maintained a calm demeanor. He considered the British his friends and was acutely aware of the formidable power of the British Army. He asserted his equal standing with Frere, stating that just as he did not interfere with Frere's administration of the Cape Colony, Frere should extend the same courtesy to Zululand.

4. Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was a pivotal conflict that ultimately led to the downfall of the independent Zulu Kingdom, despite early Zulu successes.

4.1. Causes and Outbreak

The political climate in Southern Africa in the late 1870s was dominated by British imperial ambitions to consolidate their control over the region. Frere's determination to confederate the colonies, combined with perceived Zulu military strength and independence, fueled British aggression. Ultimately, Frere issued an ultimatum to Cetshwayo, demanding that he effectively disband his army. Cetshwayo's refusal to comply with this unreasonable demand directly led to the declaration of war in 1879. Despite the outbreak of hostilities, Cetshwayo consistently sought to make peace with the British, particularly after the initial engagement.

4.2. Major Battles and Campaigns

The war began with a series of engagements that shocked the British Empire. In the initial phase, a three-pronged British attack suffered severe setbacks. The most notable was the devastating Zulu victory at the Battle of Isandlwana, where a large Zulu force overwhelmed a British camp, inflicting a decisive but costly defeat on the invaders. This battle marked the first time a major Western army was annihilated by an indigenous African force armed primarily with traditional weapons. While one British column was bogged down in the Siege of Eshowe, other British forces suffered further defeats at the Battle of Intombe and the Battle of Hlobane.

However, British follow-up victories at the Battle of Rorke's Drift and the Battle of Kambula prevented a complete collapse of British military positions. Despite the opportunity for a Zulu counterattack deep into Natal after the British retreat, Cetshwayo deliberately refused to launch such an offensive. His primary objective was to repulse the British invasion and secure a favorable peace treaty. During these negotiations, however, Cetshwayo's translator, a Dutch trader named Cornelius Vijn whom the king had imprisoned at the war's outset, reportedly relayed warnings of gathering Zulu forces to the British commander, Lord Chelmsford.

4.3. Outcome and Consequences

The British, having learned bitter lessons from their initial defeats, returned to Zululand with a significantly larger and better-equipped force. The decisive engagement came at the Battle of Ulundi, the Zulu capital, on July 4, 1879. In this battle, the British, employing tactics adapted from their Isandlwana experience, formed a strong hollow square on the open plain, fortified with cannons and Gatling guns. The engagement lasted approximately 45 minutes before the British cavalry charged the Zulu forces, routing them.

After Ulundi was captured and burned on July 4, Cetshwayo was deposed and subsequently captured on August 28. He was exiled, first to Cape Town and then to London. Following his deposition, the British declared the Zulu Kingdom a protectorate and divided it into twelve smaller chieftaincies, effectively dismantling its independent sovereignty.

5. Exile and Return

Cetshwayo's period of exile garnered him international attention and sympathy, ultimately leading to his brief return to a fractured Zululand.

5.1. Exile in British Territories

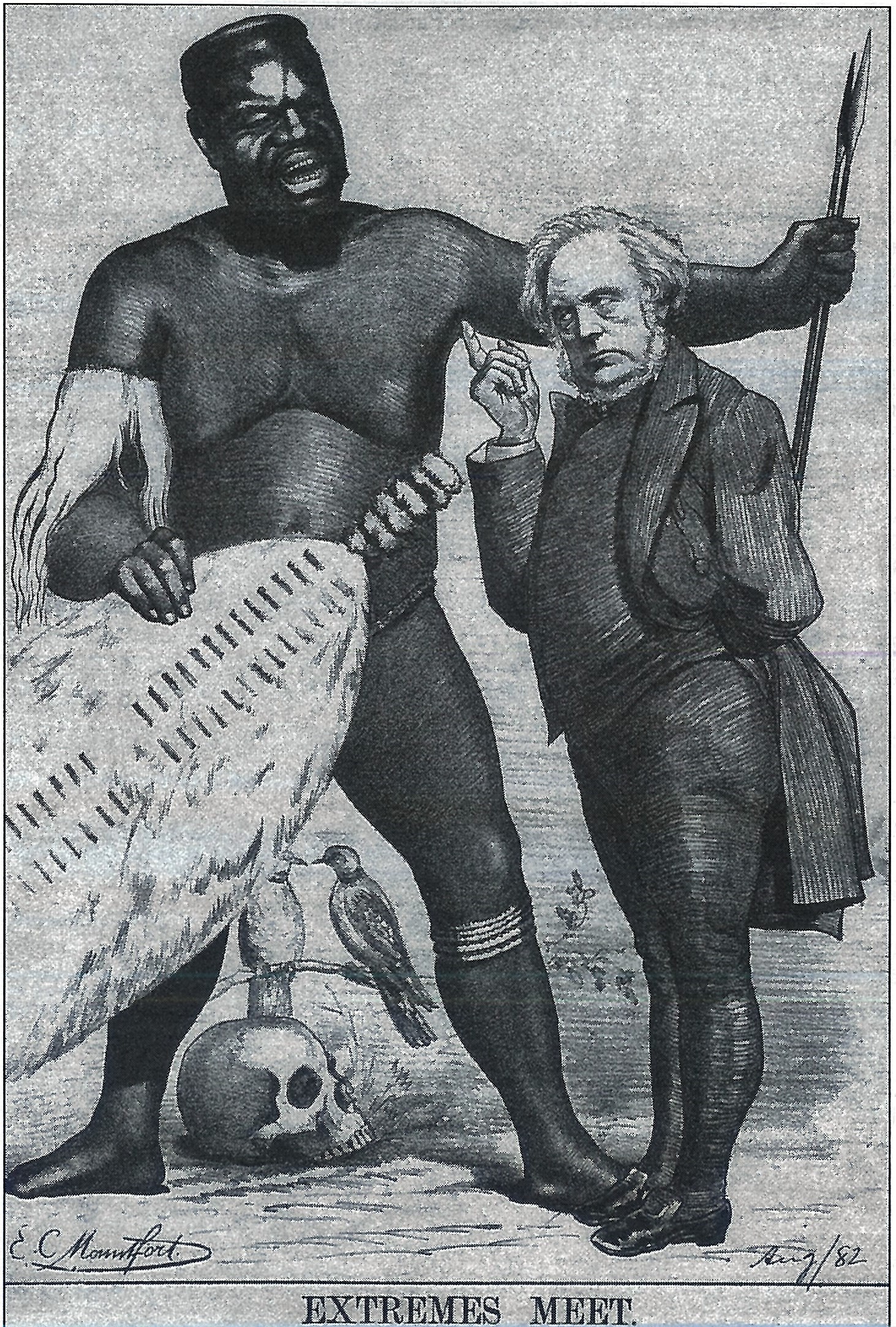

Following his capture, Cetshwayo was initially exiled to Cape Town in present-day South Africa. His cause gained significant support from various individuals, including Lady Florence Dixie, a correspondent for The Morning Post, who wrote articles and books advocating for his return. In 1882, he was allowed to relocate to London, where his dignified and gentle demeanor impressed the British public and government officials. He met with Queen Victoria, during which he formally requested his return to Zululand. This public sympathy contributed to the sentiment that he had been ill-used and poorly treated by figures like Bartle Frere and Lord Chelmsford. A cartoon by E.C. Mountfort in 1882 depicted Cetshwayo being lectured by the anti-imperialist Member of Parliament, John Bright.

5.2. Return to Zululand

Influenced by the public's perception and the growing instability in the divided Zulu territories, the British government attempted to restore Cetshwayo to rule at least a portion of his former territory in 1883. He returned to Zululand on January 10, 1883, and was reinstated as king over a significantly reduced area, with administration over the Ulundi region being returned to him. However, his influence was greatly diminished compared to his pre-war authority.

6. Later Life and Death

Cetshwayo's final years were tragically marked by internal conflicts within Zululand, culminating in his death under uncertain circumstances.

6.1. Internal Conflicts and Final Years

By 1882, even before Cetshwayo's return, deep divisions had erupted into a blood feud and civil war between two main Zulu factions: the pro-Cetshwayo uSuthus and rival chiefs, primarily led by Zibhebhu kaMaphitha. Upon his return, Cetshwayo found himself in a precarious position amidst this ongoing strife.

On July 22, 1883, Chief Zibhebhu, aided by Boer mercenaries, launched an attack on Cetshwayo's new kraal (royal enclosure) in Ulundi, specifically contesting the succession. Cetshwayo was wounded during the assault but managed to escape and found refuge in the forest at Nkandla. Following pleas from the British Resident Commissioner, Sir Melmoth Osborne, Cetshwayo moved to Eshowe under British escort in October 1883, where he remained vulnerable.

6.2. Death and Burial

Cetshwayo died a few months later in Eshowe, on February 8, 1884, at an age estimated between 57 and 60. The official cause of death was presumed to be a heart attack, as no autopsy was performed. However, there are significant theories suggesting that he may have been poisoned. This suspicion is fueled by the fact that other influential Zulu figures reportedly died under similar mysterious circumstances around the same time, leading to speculation that British or Boer factions may have been responsible.

His body was transported from Eshowe and buried in a field within sight of the Nkandla forest, near the Nkunzane River. The remains of the wagon that carried his corpse to the burial site were placed on the grave, and parts of it can still be seen today at the Ondini Museum, near Ulundi.

7. Historical Assessment

Cetshwayo's life and reign are assessed through the dual lenses of his efforts to maintain Zulu independence and the challenges he faced from internal strife and external colonial pressures.

7.1. Positive Contributions

Cetshwayo is widely regarded as a symbol of resistance against British colonial encroachment in Southern Africa. His most significant positive contribution was his unwavering commitment to preserving the independence of the Zulu Kingdom in the face of overwhelming imperial power. He actively strengthened the Zulu army, reintroducing and refining the military traditions of Shaka, demonstrating his foresight in anticipating conflict. His leadership during the Anglo-Zulu War, particularly the stunning victory at Isandlwana, showcased the effectiveness of Zulu military tactics and his ability to command a powerful fighting force. His dignified conduct during exile also earned him considerable international sympathy, highlighting the injustice of his deposition.

7.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Criticisms and controversies surrounding Cetshwayo include his forceful methods in securing his succession, such as the brutal Battle of Ndondakusuka and the elimination of rival half-brothers and their families. While these actions were part of the ruthless power dynamics of the era, they reveal a darker side to his consolidation of power. During the Anglo-Zulu War, some historians question his strategic decisions, such as his refusal to launch a full counter-offensive into Natal after the British defeats, which some argue missed a crucial opportunity to further cripple the British forces. Furthermore, the debated circumstances of his death, with theories of poisoning, remain a point of controversy, casting a shadow over the end of his life and the integrity of the colonial powers.

8. Impact and Influence

Cetshwayo's life and actions had a profound and lasting impact on Southern African history, particularly as the last king of an independent Zulu Kingdom. His reign and the Anglo-Zulu War represent a crucial turning point in the region's history, marking the end of a powerful African state's sovereignty and the acceleration of British colonial dominance. His son, Dinuzulu, was proclaimed king on May 20, 1884, succeeding Cetshwayo, albeit over a kingdom that was no longer independent. Cetshwayo's legacy endures as a figure who valiantly fought against the tide of imperialism, and he remains a significant figure in the historiography of South Africa. His historical importance is recognized through commemorations such as the King Cetshwayo District Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal, which was named after him in 2016.

9. In Popular Culture

Cetshwayo's dramatic life and role in the Anglo-Zulu War have led to his portrayal in various forms of popular culture:

- Literature: He appears in three adventure novels by H. Rider Haggard: The Witch's Head (1885), Black Heart and White Heart (1900), and Finished (1917), as well as in Haggard's non-fiction work Cetywayo and His White Neighbours (1882). He is mentioned in John Buchan's novel Prester John and in O. Henry's short story A Municipal Report from Strictly Business (1910), where a character's face is compared to "King Cettiwayo." J. M. Coetzee also makes a brief allusion to him in his novel Age of Iron.

- Opera: A character in the 1889 opera Leo, the Royal Cadet by Oscar Ferdinand Telgmann and George Frederick Cameron was named in his honor.

- Film and Television:

- In the 1964 film Zulu, Cetshwayo was played by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who was his maternal great-grandson and later became a prominent South African political leader.

- In the 1979 film Zulu Dawn, he was portrayed by Simon Sabela.

- In the 1986 miniseries Shaka Zulu, Sokesimbone Kubheka played him.

- Video Games: In the "Scramble for Africa" scenario of Civilization V: Brave New World, Cetshwayo is featured as the leader of the Zulus.

10. Commemoration and Legacy

Cetshwayo's legacy is formally recognized through various commemorative acts. The King Cetshwayo District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa was named in his honor in 2016, acknowledging his significant place in the region's history. In London, a blue plaque commemorates his stay at 18 Melbury Road in Kensington during his exile in 1882. These commemorations ensure his enduring place in public memory as a pivotal figure in the history of the Zulu people and the broader struggle against colonialism in Southern Africa.

11. External links

- [http://africanhistory.about.com/library/biographies/blbio-cetshwayo.htm Biography of Cetshwayo kaMpande, the last king of an independent Zulu nation]