1. Name

Throughout the Middle Ages, manuscripts of Gellius's sole known work, Noctes Atticae (Attic Nights), frequently rendered the author's name as "Agellius." This form was notably adopted by the grammarian Priscian. However, other prominent ancient writers such as Lactantius, Servius, and Saint Augustine consistently referred to him as "A. Gellius." From the Renaissance onward, scholars engaged in a vigorous debate over which of these two transmitted names was the correct one, with the other presumed to be a corruption. Modern scholarship has largely settled on "A. Gellius" as the accurate form.

2. Life

The primary source of information regarding the life of Aulus Gellius is the biographical details he recorded within his own writings. These internal accounts allow for a reconstruction of his experiences and intellectual development.

2.1. Early life and education

Aulus Gellius was likely born in Rome between approximately 125 and 128 AD, and he was certainly brought up in the city. He hailed from a respectable family with good connections, and some evidence suggests his family may have had origins in Africa. His early education in Rome focused on grammar and rhetoric. He later traveled to Athens, where he resided for a considerable period, possibly after 143 AD, to further his studies, specializing in philosophy.

During his educational journey, Gellius benefited from the instruction and friendship of several prominent figures of his time. He studied rhetoric under Titus Castricius and Sulpicius Apollinaris, and philosophy under Calvisius Taurus and Peregrinus Proteus. He also enjoyed the company and guidance of esteemed intellectuals such as Favorinus, Herodes Atticus, and Marcus Cornelius Fronto. In 147 AD, Gellius is known to have attended the Pythian Games.

2.2. Career and public office

Following his extensive education in Athens, Gellius returned to Rome, where he took up a judicial office. He was appointed by the praetor to serve as an umpire in civil causes. This public duty, while important, significantly occupied his time, often limiting the hours he would have preferred to dedicate to his literary pursuits.

3. Works

Aulus Gellius is known for only one literary contribution, the Attic Nights, a unique compilation that reflects his intellectual curiosity and serves as an invaluable historical record.

3.1. Attic Nights (Noctes Atticae)

Gellius's sole known work is the Attic Nights, or Noctes AtticaeLatin. The title is derived from the fact that he began compiling the work during the long winter nights he spent in Attica. He continued its composition upon his return to Rome. The work originated from his personal Adversaria, a commonplace book where he meticulously jotted down anything he found particularly interesting, whether heard in conversation or encountered during his extensive reading.

The Attic Nights is deliberately structured without a strict sequence or arrangement, reflecting its nature as a collection of miscellaneous notes. It is divided into twenty books, all of which have survived except for the eighth, of which only its index remains. The subjects covered are remarkably diverse, encompassing grammar, geometry, philosophy, history, antiquarianism, language, original text criticism, literary criticism, ancient studies, and many other topics. Notably, the collection includes the fable of Androcles, which, though often associated with Aesop's fables, did not originate from that source. Internal evidence suggests the work was published in or after 177 AD.

The immense value of Attic Nights lies in several key aspects. It offers a unique insight into the nature of Roman society and the intellectual pursuits of the Antonine period. More importantly, it preserves numerous excerpts from the works of lost ancient authors, many of whom might otherwise be entirely unknown today. The work was widely read in antiquity and served as a rich source for subsequent writers and scholars. Among those who utilized Gellius's compilation were Apuleius, Lactantius, Nonius Marcellus, Ammianus Marcellinus, the anonymous author of the Historia Augusta, Servius, and Augustine. Most notably, Macrobius extensively drew from Gellius's work, quoting him verbatim throughout his Saturnalia without explicit attribution, thereby making Gellius's text crucial for understanding Macrobius's own writings. The Korean source also notes that it was a Latin essay collection written for children.

4. Editions and Translations

The Attic Nights has been the subject of numerous significant editions and translations throughout history, contributing to its continued study and accessibility.

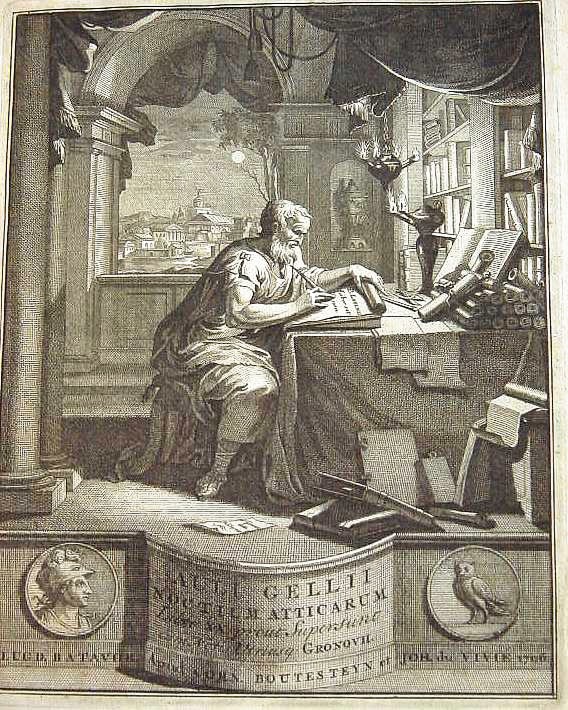

The editio princeps, the first printed edition, was published in Rome in 1469 by Giovanni Andrea Bussi, who was the bishop-designate of Aleria. The earliest critical edition was produced by Ludovicus Carrio in 1585, published by Henricus Stephanus, although its projected commentary was never completed due to personal disputes. A more renowned critical edition was undertaken by Johann Friedrich Gronovius, who dedicated his entire life to the study of Gellius. He died in 1671 before his work could be finalized. His son, Jakob Gronovius, subsequently published most of his father's comments on Gellius in 1687 and later issued a revised text incorporating all of his father's notes and additional materials in Leyden in 1706. This latter work became famously known as the "Gronoviana" and remained the standard text of Gellius for over a century. Later editions include that of Martin Hertz (Berlin, 1883-85), with a smaller edition published in 1886, which was later revised by C. Hosius in 1903. A volume of selections, complete with notes and vocabulary, was published by Nall in London in 1888. More recently, Peter K. Marshall's edition (Oxford University Press, 1968, reissued with corrections in 1990) has become widely used in both print and digital formats.

Notable translations of Attic Nights include an English translation by W. Beloe (London, 1795) and a French translation (1896). A more recent and widely used English translation is that by John Carew Rolfe (1927) for the Loeb Classical Library. In Japan, a translation into Japanese was published by Hidemichi Onishi through the Kyoto University Press in 2016, as part of the Western Classics Series.

5. Assessment and Legacy

Aulus Gellius and his Attic Nights hold a significant place in the history of classical scholarship and literature. The work's enduring legacy stems from its dual role as both a window into the intellectual life of the Roman Empire and a vital repository of lost ancient texts.

Scholars have consistently valued Attic Nights as an indispensable source for understanding the nuances of ancient literature, philosophy, and Roman culture. Its eclectic nature, encompassing diverse subjects from grammar to history and philosophy, provides a comprehensive snapshot of the knowledge and intellectual interests prevalent during Gellius's time. The numerous direct quotations and paraphrases from otherwise lost Greek and Roman works make Attic Nights a crucial resource for reconstructing fragments of ancient thought and literature. This preservation function has cemented Gellius's importance for subsequent generations of scholars and writers, who have relied on his compilation as a primary reference for accessing and studying the classical world. His work's influence on later authors, particularly Macrobius, further underscores its lasting impact on the transmission of knowledge in antiquity.