1. Overview

Alice is a fictional character and the central protagonist of Lewis Carroll's seminal children's novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass (1871). As a child living in the mid-Victorian era, Alice embarks on an unintentional underground adventure after tumbling down a rabbit hole into the fantastical world of Wonderland. In the subsequent narrative, she steps through a mirror into an alternative realm known as Looking-Glass World.

The character's genesis lies in stories improvised by Carroll, whose real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, to entertain the Liddell sisters during rowing excursions on the Isis with his friend Robinson Duckworth, and continuing on subsequent trips. While the character shares her given name with Alice Liddell, a scholarly debate persists regarding the extent to which Alice's character was directly based on Liddell. Carroll himself characterized Alice as "loving and gentle," "courteous to all," "trustful," and "wildly curious," embodying the "eager enjoyment of Life that comes only in the happy hours of childhood, when all is new and fair, and when Sin and Sorrow are but names - empty words signifying nothing!"

Alice is widely regarded as a significant cultural icon. She marked a notable departure from the typical 19th-century child protagonists, often depicted as didactic figures or moral examples. Her critical, questioning nature and occasional defiance of absurd authority figures within Wonderland resonate with a progressive viewpoint on childhood autonomy and challenging established norms. The immense success of the two Alice books inspired countless sequels, parodies, and imitations, featuring protagonists who shared Alice's temperament, often exhibiting politeness, articulation, and assertiveness regardless of gender. The character has been subject to various critical interpretations, including psychoanalytic approaches that explore deeper psychological and societal implications. Alice has been extensively re-imaginéd and adapted across numerous media, most notably in Walt Disney's animated film (1951), and her enduring appeal is often attributed to her remarkable adaptability and capacity for continuous re-interpretation in different cultural contexts, such as her significant reception in Japan.

2. Conception and Development

Alice's character underwent significant evolution from her initial conception as a spontaneous oral narrative to her established visual representations that have shaped her enduring popular image.

2.1. Initial Conception and Carroll's Illustrations

Alice first appeared in Lewis Carroll's preliminary draft of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, which was initially titled Alice's Adventures Under Ground. This foundational work originated from stories Carroll recounted spontaneously to the Liddell sisters on the afternoon of July 4, 1862, while rowing on the Isis with his friend Robinson Duckworth, a narrative practice that continued on subsequent rowing excursions. At the specific request of ten-year-old Alice Liddell, Carroll committed these stories to paper, completing Alice's Adventures Under Ground in February 1864.

The manuscript of Under Ground features 37 illustrations drawn by Carroll himself, with Alice depicted in 27 of them. However, Carroll's drawings of Alice bear minimal physical resemblance to Alice Liddell, the girl who shares her given name and inspired the initial telling of the stories. This discrepancy has led to speculation that Alice Liddell's younger sister, Edith, might have served as Carroll's model for the character's physical appearance in these early illustrations. Carroll portrayed his protagonist wearing a loose tunic dress, which contrasted sharply with the more tailored and formal dresses that girls like the Liddell sisters would typically have worn during that period. His artistic style in these illustrations was influenced by Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Arthur Hughes. Notably, Carroll visually alluded to Hughes' painting The Lady with the Lilacs (1863) in one of his drawings within Under Ground, showcasing his aesthetic preferences. Carroll presented the hand-written manuscript of Alice's Adventures Under Ground to Alice Liddell in November 1864.

The degree to which the character of Alice can be definitively identified with Alice Liddell remains a subject of ongoing controversy among scholars. While some critics argue that the character is directly based on Liddell or that she served as the primary inspiration, others contend that Carroll consistently considered his literary protagonist and the real Alice Liddell to be distinct entities. Carroll himself, in his later writings, maintained that his character was entirely fictional and not based on any specific real child, a stance that adds complexity to the debate.

2.2. John Tenniel's Illustrations

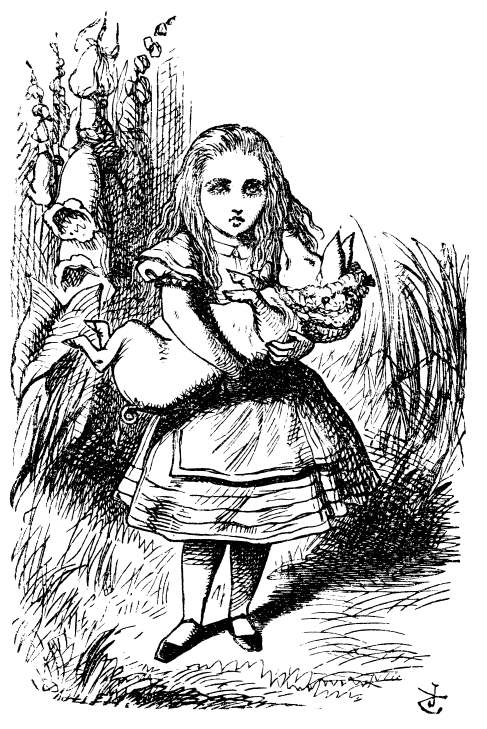

John Tenniel played a pivotal role in shaping Alice's enduring and widely recognized public image through his distinctive illustrations for both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Carroll commissioned Tenniel as the illustrator in April 1864, paying him a fee of 138 GBP for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, an amount roughly equivalent to a quarter of Carroll's annual earnings, which he personally covered. At the time of his employment, Tenniel was already a highly successful and well-known lead illustrator for the satirical magazine Punch, while Carroll, in contrast, had not yet achieved significant literary fame.

Tenniel is believed to have based the majority of his illustrations on Carroll's own drawings from Alice's Adventures Under Ground. Carroll meticulously oversaw Tenniel's work, providing detailed suggestions. Among these, he specifically requested that Alice be depicted with long, light-coloured hair, a departure from Carroll's earlier black-haired renditions. Tenniel's portrayal of Alice's attire was characteristic of what a middle-class girl in the mid-Victorian era would typically have worn at home. The pinafore dress, a distinctive detail created by Tenniel, became intrinsically linked with the character and has been noted for suggesting "a certain readiness for action and lack of ceremony," reflecting a practical and unpretentious aspect of Alice's persona.

Tenniel's visual concept for Alice was not entirely novel; it had origins in a physically similar character who appeared in at least eight cartoons published in Punch magazine over a four-year period beginning in 1860. In an 1860 cartoon, this antecedent character wore clothing now associated with Alice, including "the full skirt, pale stockings, flat shoes, and a hairband over her loose hair." In these cartoons, the character functioned as an archetype of a pleasant, middle-class girl, described as "a pacifist and noninterventionist, patient and polite, slow to return the aggression of others," traits that strongly align with Alice's disposition.

For the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, Tenniel's fee increased to 290 GBP, which Carroll again paid out of his own pocket. In this second volume, Tenniel subtly altered Alice's clothing. She is shown wearing horizontal-striped stockings instead of plain ones, and her pinafore is more ornately designed with a prominent bow. Interestingly, Carroll rejected an initial design by Tenniel that depicted Alice as a queen wearing a "crinoline-supported chessmanlike skirt," similar to those worn by the Red and White Queens in the story. However, Alice's attire when she becomes a queen and also in the railway carriage scenes, features a polonaise-styled dress with a bustle, which was a fashionable style at the time. The clothing worn by characters in John Millais's Pre-Raphaelite painting "My First Sermon" (1863) and Augustus Leopold Egg's Victorian painting "The Travelling Companions" (1862) share some common elements with Alice's railway carriage attire. Despite Tenniel's significant contributions, Carroll expressed dissatisfaction with the artist's refusal to use a live model for Alice's illustrations, which Carroll believed resulted in her head and feet appearing out of proportion.

2.3. Evolution of Appearance

Beyond John Tenniel's definitive illustrations, Alice's physical appearance, including her hair color, clothing style, and overall visual representation, continued to evolve through various subsequent publications and the interpretations of numerous other illustrators.

In February 1881, Carroll initiated discussions with his publisher about producing The Nursery "Alice", a simplified edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland featuring coloured and enlarged illustrations. For this project, Tenniel colored 20 of his original illustrations from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and also revised certain aspects of them. In The Nursery "Alice", Alice is distinctly depicted as a blonde, and her dress is colored yellow, complemented by blue stockings. Her dress was redesigned to be pleated with a bow at the back, and she wore a matching bow in her hair. Edmund Evans was responsible for printing these coloured illustrations using chromoxylography, a technique that utilized woodblocks to produce vibrant colour prints.

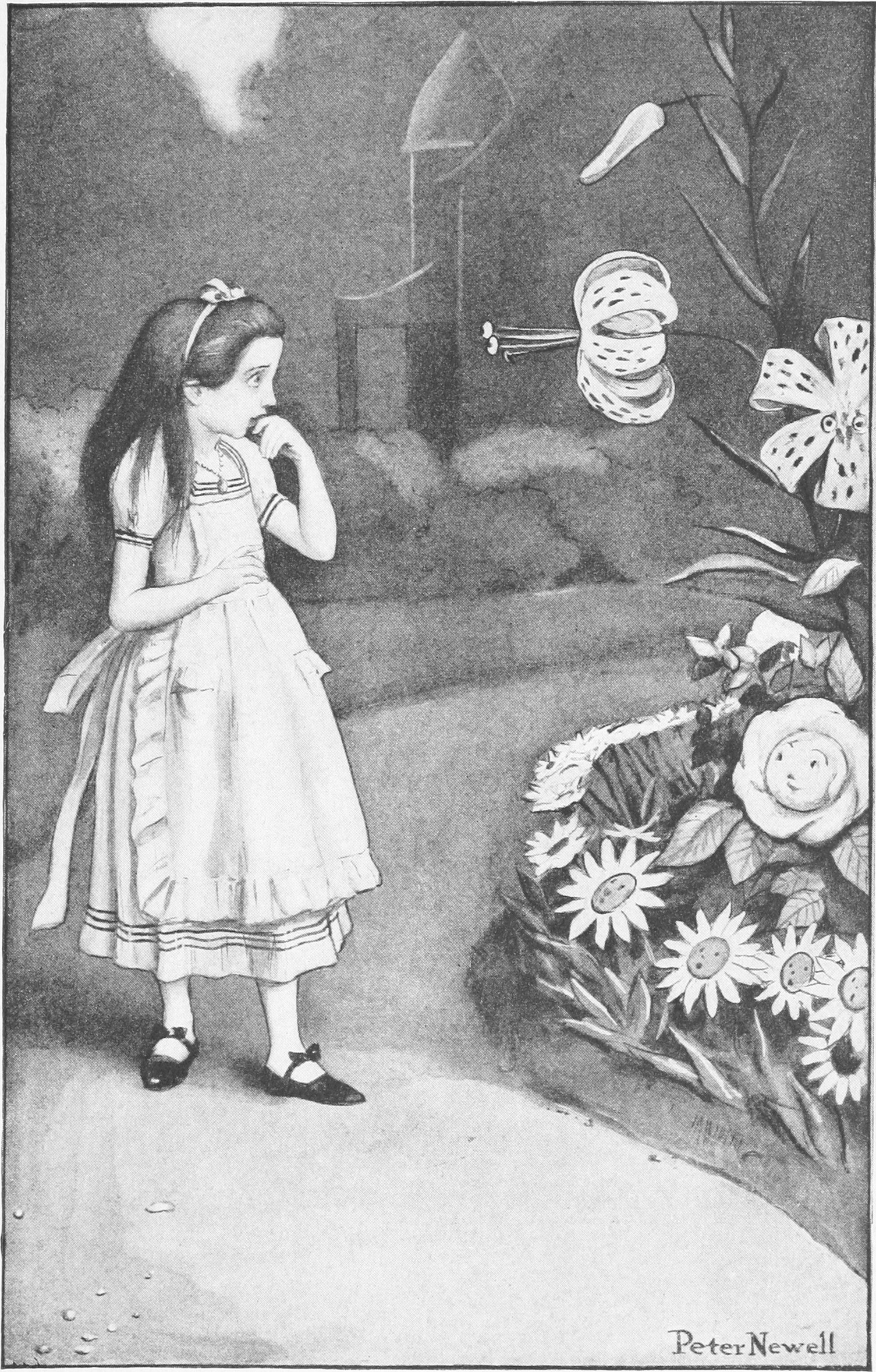

The two Alice books have been frequently re-illustrated by a wide array of artists over the decades. The expiration of the copyright for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1907 led to a surge in new printings, including a notable edition illustrated in an Art Nouveau style by Arthur Rackham. Other illustrators whose editions were published in 1907 included Charles Robinson, Alice Ross, W. H. Walker, Thomas Maybank, and Millicent Sowerby. Among the other prominent illustrators who contributed to Alice's visual history are Blanche McManus (1896), Peter Newell (1901), who utilized a monochrome style; Mabel Lucie Atwell (1910); Harry Furniss (1926); and Willy Pogany (1929), whose work exhibited an Art Deco style.

From the 1930s onward, new generations of illustrators continued to reimagine Alice. Notable artists from this period include Edgar Thurstan (1931), whose illustrations contained visual allusions to the Wall Street Crash of 1929; D.R. Sexton (1933) and J. Morton Sale (1933), both of whom depicted a more mature Alice; Mervyn Peake (1954), whose distinctive style garnered critical acclaim; Ralph Steadman (1967), who received the Francis Williams Memorial Award in 1972 for his work; Salvador Dalí (1969), who brought his signature Surrealism to the books; and Peter Blake (1970), who used watercolours. By 1972, there were already 90 illustrators for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and 21 for Through the Looking-Glass, demonstrating the character's appeal to artists. In the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, prominent illustrators included Barry Moser (1982); Greg Hildebrandt (1990); David Frankland (1996); Lisbeth Zwerger (1999), known for her watercolours; Helen Oxenbury (1999), who earned both the Kurt Maschler Award and the Kate Greenaway Medal for her contributions; and DeLoss McGraw (2001), with his distinctive abstract illustrations.

3. Character Traits

Alice as a fictional character is defined by a unique combination of personality traits, a specific age and fictional family background, and a social standing that reflects her Victorian upbringing.

3.1. Personality

In "Alice on the Stage" (April 1887), Carroll articulated Alice's character as "loving and gentle," "courteous to all," "trustful," and "wildly curious, and with the eager enjoyment of Life that comes only in the happy hours of childhood, when all is new and fair, and when Sin and Sorrow are but names - empty words signifying nothing!" This description emphasizes her inherent innocence and boundless curiosity.

Commentators have consistently characterized Alice as "innocent," "imaginative," and introspective. She is generally depicted as well-mannered, yet also notably critical of authority figures and clever. This blend of politeness and skepticism allows her to question the nonsensical rules and illogical behavior she encounters in Wonderland, a trait that aligns with a perspective that values independent thought and critical analysis of power structures.

However, some critics also identify less positive aspects of Alice's personality. She frequently exhibits a degree of unkindness in her interactions with the animals she encounters in Wonderland. For instance, she takes a physically aggressive action against Bill the Lizard, kicking him into the air. These behaviors, along with occasional impolite replies and a perceived lack of sensitivity, are sometimes seen as reflections of her upper-class Victorian upbringing and its associated prejudices. As Donald Rackin observes, "In spite of her class- and time-bound prejudices, her frightened fretting and childish, abject tears, her priggishness and self-assured ignorance, her sometimes blatant hypocrisy, her general powerlessness and confusion, and her rather cowardly readiness to abandon her struggles at the ends of the two adventures-[....] many readers still look up to Alice as a mythic embodiment of control, perseverance, bravery, and mature good sense." This complex portrayal suggests that despite her flaws, Alice embodies admirable qualities of resilience and rational thought in the face of absurdity.

Literary analysis suggests that while Carroll may have drawn on Alice Liddell for Alice's physical creation, the character's personality was largely a projection of Carroll's own nature. This interpretation is supported by observations that Carroll, also known as Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, meticulously maintained two distinct personas: that of the mathematician and that of the children's author, Lewis Carroll, which parallels Alice's own internal dialogues and self-correction throughout her adventures.

3.2. Age and Fictional Background

Alice is portrayed as a child living in the midst of the Victorian era. In Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, which is understood to take place on May 4, the character is widely assumed to be seven years old. This date holds particular significance as May 4 is the birthday of Alice Liddell, and a photograph of Alice Liddell at age seven was affixed to the final page of Carroll's original hand-written manuscript, Alice's Adventures Under Ground. In the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, which is set on November 4, Alice explicitly states her age as seven and a half, precisely half a year older than in the first book.

Carroll typically provided minimal descriptions of his protagonist's physical appearance within the text of the two Alice books. However, details of her fictional life can be inferred from the narratives. At home, Alice has a significantly older sister, whose name is not specified, and a brother. She also lives with a beloved pet cat named Dinah, an elderly nurse, and a governess who supervises her lessons starting at nine o'clock each morning. The text further indicates that Alice had attended a day school at some point in her backstory, suggesting a structured upbringing common for girls of her social standing. In Through the Looking-Glass, Dinah makes an appearance with her kittens, Kitty (a black cat who plays a mischievous role) and Snowdrop (a white cat). The name Dinah was, in fact, the name of a real cat owned by the Liddell family, as was "Wilkins," named after a popular contemporary song "Wilkins and his Dinah." Snowdrop was also the name of a cat belonging to Mary MacDonald, one of Carroll's early child friends.

3.3. Social Class and Education

Alice is consistently characterized as belonging to the wealthy segment of the Victorian era's gentry or middle class, sometimes even identified with the bourgeoisie. This social standing is clearly reflected in various aspects of her fictional life and education.

For instance, in Chapter 9 of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Alice asserts that she attends school daily, a privilege that contrasts with the Mock Turtle's lament that he could only afford "the regular course" of lessons due to economic constraints. Alice further boasts that, beyond her standard curriculum, she also studies French and music. This detail highlights the typical educational expectations for girls of her class, which often prioritized accomplishments like language and music over rigorous academic subjects, reflecting the prevailing societal view that a girl's education should prepare her for a refined domestic life rather than serious intellectual pursuits. This emphasis on superficial rather than substantive knowledge can be viewed as a subtle critique of Victorian middle-class education for girls.

Alice's class consciousness is also evident in her own perceptions. In Chapter 2, she expresses her dismay at the possibility of transforming into her classmate, Mabel, specifically noting that she would not want to be a child from a family living in a "small, dirty house." Her indignation when the Mock Turtle asks her if she learned "washing" during her education further underscores her social conditioning, as learning such a practical skill was likely considered beneath a girl of her standing.

Carroll's original intention was for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland to primarily appeal to children from middle-class backgrounds. The protagonist, Alice, was therefore consciously crafted as a girl from this very social stratum. Even John Tenniel's illustrations of Alice's clothing were not merely a reflection of his or Carroll's personal tastes but were designed to represent the typical, conservative, and practical everyday wear of a Victorian middle-class girl, further cementing her identity within that social context.

4. Attire

Alice's distinctive clothing, particularly her iconic blue dress and white pinafore, has become an indelible part of her character's identity and has exerted a lasting influence on fashion and popular culture.

4.1. Design and Evolution

Although there is little explicit textual description of Alice's clothing in Lewis Carroll's novels, Carroll provided detailed instructions to John Tenniel regarding the character's attire for his illustrations. Tenniel's pivotal illustrations established Alice's iconic look: a pinafore dress, consisting of a bodice, a wide skirt, and an apron. This dress featured short puff sleeves and included tucks at the hem, allowing for it to be lengthened as Alice grew. The fabric choices for such dresses during that era often included washable materials like poplin, high-quality alpaca, or pique. The apron, typically made of practical Holland cloth or cambric, further emphasized the practical and unceremonious nature of her attire. Her flat, lace-up shoes were designed for freedom of movement, allowing her to run and explore.

In the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, Tenniel made slight modifications to Alice's outfit. While the overall style remained consistent, her apron gained decorative frills and a prominent large bow at the back. Additionally, her plain stockings were replaced with striped ones. A hairband was also added to her head in these illustrations, a style accessory that would later become famously known as the "Alice band."

Initially, in his handwritten manuscript Alice's Adventures Under Ground, Carroll had illustrated Alice wearing a simpler, unadorned, and loose medieval-style dress, influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite painters he admired. However, this aesthetic was not widely accepted by general British households at the time. Therefore, when Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was officially published, Carroll and Tenniel opted for a more conventional design that aligned with the preferences of the intended middle-class readership, leading to the familiar pinafore. This practical and unassuming attire for Alice often serves to contrast her with the fantastical, often anachronistically dressed inhabitants of Wonderland, thereby emphasizing her role as an ordinary girl who has stumbled into an extraordinary realm. This stylistic choice effectively highlights the idea that Alice has wandered into another dimension.

Later adaptations and illustrations, particularly those for operetta versions of Alice, frequently retained Tenniel's costume designs for the fantastical inhabitants of Wonderland, while adapting Alice's own attire to reflect the contemporary fashion of middle-class girls. This trend continued in the coloration of her dress; while Tenniel's own colored illustrations for The Nursery "Alice" (1889) depicted her dress as yellow, Walt Disney's 1951 animated film popularized a blue (specifically, sax blue) pinafore, influencing subsequent portrayals. Disney's Alice also features a black hairband with a black ribbon and plain white tights.

4.2. Cultural Impact of Attire

Alice's distinctive clothing, particularly the blue dress and white pinafore, has achieved the status of a widely recognized cultural symbol and has profoundly influenced fashion trends. The Alice band, a style of hairband she is depicted wearing in Tenniel's illustrations, is directly named after her, demonstrating her lasting impact on accessories.

Walt Disney's 1951 film adaptation, despite earlier unauthorized American editions (such as Thomas Crowell's 1893 publication) that depicted Alice as a blonde in a blue dress, was particularly instrumental in solidifying this specific popular image of Alice. Disney's visual portrayal drew from both Mary Blair's concept drawings and Tenniel's illustrations. The ubiquitous nature of "Alice in a blue dress" in popular culture is so pervasive that, as critics Zoe Jaques and Eugene Giddens note, she is "as ubiquitous as Hamlet holding a skull," creating a unique situation where the public often "knows" Alice without having read either Wonderland or Looking-Glass. This widespread recognition allows for considerable creative freedom in subsequent adaptations, often enabling creators to overlook strict faithfulness to the original texts.

In Japan, Alice's attire, along with her overall character, has had a significant impact on popular culture, particularly influencing Lolita fashion. This highly distinctive street style frequently incorporates elements of Alice's iconic design, with numerous brands releasing products that closely reproduce her historical look. Alice's popularity in Japan, and her influence on fashion like Lolita, is often attributed to her embodiment of the shōjo ideal-a Japanese concept of girlhood that combines an outwardly "sweet and innocent" demeanor with an "autonomous" inner spirit, resonating with a desire for both traditional charm and inner strength.

5. Cultural Impact and Interpretations

Alice's character has had an enduring influence and has been subject to diverse interpretations across literature, critical analysis, and global popular culture, cementing her status as a cultural icon.

5.1. Literary and Critical Reception

Alice has been widely recognized as a cultural icon. The Alice books have consistently remained in print since their initial publication, with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland available in over a hundred languages. The first book has frequently appeared on surveys of top children's books, and Alice herself was ranked among the top twenty favorite characters in children's literature in a 2015 British survey.

Both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass achieved critical and commercial success during Lewis Carroll's lifetime. By 1898, over 150,000 copies of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and 100,000 copies of Through the Looking-Glass had been printed. Victorian readers generally enjoyed the Alice books as light-hearted entertainment, appreciating their departure from the didacticism and "stiff morals" often found in other children's literature of the period. The Spectator described Alice as "a charming little girl, [...] with a delicious style of conversation," while The Publisher's Circular praised her as "a simple, loving child." Many reviewers believed that John Tenniel's illustrations significantly enhanced the books, with The Literary Churchman remarking that Tenniel's art of Alice provided "a charming relief to all the grotesque appearances which surround her."

Later literary critics have highlighted Alice's character as unusual or a significant departure from the typical child protagonists of the mid-nineteenth century. Richard Kelly views Alice as Carroll's innovative rework of the Victorian orphan trope. Unlike traditional orphans who undergo moral and societal transformation, Alice is forced to rely on herself in Wonderland, facing an intellectual struggle to maintain her sense of identity against its peculiar inhabitants. Alison Lurie argues that Alice actively defies the gendered, mid-Victorian conceptions of the idealized girl. Alice's temperament does not conform to this ideal, and her willingness to challenge the adult figures in Wonderland represents a subversive stance, promoting the idea of critical engagement and questioning authority. The influence of the two Alice books on the literary field began as early as the mid-Victorian era, inspiring various novels that adopted their style, served as parodies of contemporary political issues, or re-worked elements of the original Alice books. These literary successors often featured protagonists, regardless of gender, who shared Alice's characteristics, typically being polite, articulate, and assertive.

From the 1930s to the 1940s, the Alice books came under intense scrutiny from psychoanalytic literary critics. Freudians proposed that the events depicted in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland reflected the personality and latent desires of the author, primarily because the original stories had been told spontaneously. In 1933, Anthony Goldschmidt introduced the concept of "Carroll as a repressed sexual deviant," theorizing that Alice served as Carroll's representation in the novel, though Goldschmidt's influential work has since been questioned as a potential hoax. Regardless of this, Freudian analysis identified numerous symbols in the books as "classic Freudian tropes," including "a vaginal rabbit hole and a phallic Alice, an amniotic pool of tears, hysterical mother figures and impotent father figures, threats of decapitation [castration], swift identity changes." These interpretations offer a critical lens through which to explore the psychological underpinnings of the narrative and its characters.

5.2. Visual Adaptations and Popular Image

Walt Disney created an immensely influential representation of Alice in his 1951 film adaptation, becoming what some described as "the single greatest rival of Tenniel" in shaping Alice's image within popular culture. While Alice had appeared as a blonde in a blue dress in an unauthorized American edition of the two Alice books published by Thomas Crowell in 1893-possibly for the first time-Disney's portrayal was the most influential in solidifying this popular image. Disney's version of Alice drew its visual basis from Mary Blair's concept drawings and Tenniel's illustrations. Although the film was not a commercial success during its original theatrical run, it later gained significant popularity among college students, who often interpreted the film as a narrative infused with drug references. In 1974, Alice in Wonderland was re-released in the United States with advertisements that explicitly played on this association, a connection that persists as an "unofficial" interpretation despite the film's status as family-friendly entertainment.

In the twenty-first century, Alice's continuing appeal is widely attributed to her remarkable ability to be continuously re-imaginéd by various artists and creators. Catherine Robson, in Men in Wonderland, asserts that "In all her different and associated forms-underground and through the looking glass, textual and visual, drawn and photographed, as Carroll's brunette or Tenniel's blonde or Disney's prim miss, as the real Alice Liddell [...] Alice is the ultimate cultural icon, available for any and every form of manipulation, and as ubiquitous today as in the era of her first appearance." Robert Douglass-Fairhurst compares Alice's cultural status to "something more like a modern myth," suggesting that her capacity to serve as an "empty canvas" for "abstract hopes and fears" allows new "meanings" to be ascribed to the character across generations. Zoe Jaques and Eugene Giddens highlight her ubiquitous presence in popular culture, stating that "Alice in a blue dress is as ubiquitous as Hamlet holding a skull," leading to the peculiar phenomenon where the public "knows" Alice without necessarily having read either Wonderland or Looking-Glass. This widespread recognition, they argue, provides creative freedom in subsequent adaptations, allowing for deviations from textual faithfulness.

Alice has also had a significant and unique influence on Japanese popular culture. Tenniel's original artwork and Disney's film adaptation are credited as key factors in the sustained positive reception of the two novels in Japan. Within Japanese youth culture, Alice has been adopted as "a rebellion figure in much the same way as the American and British 1960s 'hippies' did," embodying a spirit of independence and nonconformity. She has also served as a notable source of inspiration for Japanese fashion, particularly Lolita fashion, where her classic attire is frequently referenced and reinterpreted. Her widespread popularity in Japan is often attributed to the idea that she embodies the shōjo ideal-a Japanese concept of girlhood that combines an outwardly "sweet and innocent" demeanor with an "autonomous" inner spirit, resonating with a desire for both traditional charm and inner strength.

5.3. Portrayals in Media

Alice's enduring popularity has led to countless portrayals across various media, including stage productions, feature films, and television series, with many notable actors and voice actors bringing the character to life.

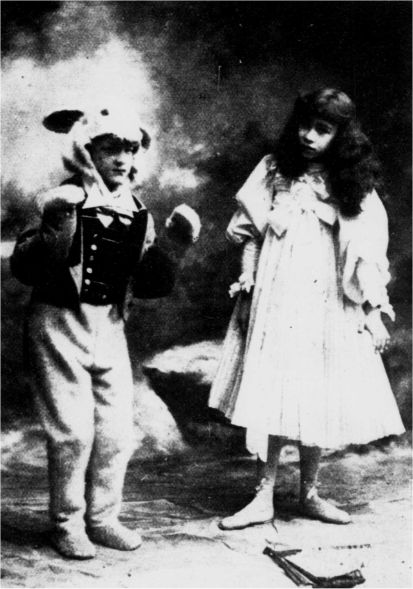

During Carroll's lifetime, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was adapted into an operetta in 1886, with a script by Henry Savile Clarke. Carroll himself recommended Phoebe Carlo for the role of Alice. Later, Isa Bowman, who also played Alice in a revival of the operetta, became a close friend of Carroll's, and he subsequently dedicated his novel Sylvie and Bruno to her. The operetta version of Alice became a popular staple during the Christmas season and enjoyed a remarkable run of over 40 years. Beyond operettas, Alice has been adapted for numerous stage productions, including plays, operas, ballets, and pantomimes, with countless actresses portraying the character in various countries.

The following actresses have notably portrayed Alice in film adaptations:

- May Clark in the 1903 film Alice in Wonderland, which was the first cinematic adaptation of Alice, an 8-minute silent film resembling a series of tableaux.

- Viola Savoy in W. W. Young's 1915 film Alice in Wonderland.

- Ruth Gilbert in Bud Pollard's 1931 film Alice in Wonderland.

- Charlotte Henry in Norman Z. McLeod's 1933 film Alice in Wonderland, marking the first time Alice was portrayed in a sound film.

- Fiona Fullerton in William Sterling's 1972 film Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, where she played Alice at the age of 15.

- Natalie Gregory in Harry Harris's 1985 film Alice in Wonderland.

- Kristýna Kohoutová in Jan Švankmajer's 1988 film Alice, a unique blend of live-action and stop-motion animation, where Kohoutová conveyed a taciturn and cold impression of Alice.

- Kate Beckinsale in John Henderson's 1998 film Alice Through the Looking Glass, where a mother reads the book to her child, who then enters the story; a 25-year-old Beckinsale played Alice in this film.

- Tina Majorino in Nick Willing's 1999 film Alice in Wonderland.

- Mia Wasikowska in Tim Burton's 2010 film Alice in Wonderland, portraying a 19-year-old Alice who returns to Wonderland as an adult.

In animated productions, Kathryn Beaumont famously provided the voice for Alice in Walt Disney's 1951 animated film. From 2005 onward, Hynden Walch took over the role for subsequent Disney productions. In the Japanese dubs, Mika Doi initially voiced Alice, later succeeded by Sumire Morohoshi. For the 1983-1984 German-Japanese co-production of the television anime series Fushigi no Kuni no Alice, TARAKO provided Alice's voice.